Biology:H3K4me3

H3K4me3 is an epigenetic modification to the DNA packaging protein Histone H3 that indicates tri-methylation at the 4th lysine residue of the histone H3 protein and is often involved in the regulation of gene expression.[1] The name denotes the addition of three methyl groups (trimethylation) to the lysine 4 on the histone H3 protein.

H3 is used to package DNA in eukaryotic cells (including human cells), and modifications to the histone alter the accessibility of genes for transcription. H3K4me3 is commonly associated with the activation of transcription of nearby genes. H3K4 trimethylation regulates gene expression through chromatin remodeling by the NURF complex.[2] This makes the DNA in the chromatin more accessible for transcription factors, allowing the genes to be transcribed and expressed in the cell. More specifically, H3K4me3 is found to positively regulate transcription by bringing histone acetylases and nucleosome remodelling enzymes (NURF).[3] H3K4me3 also plays an important role in the genetic regulation of stem cell potency and lineage.[4] This is because this histone modification is more-so found in areas of the DNA that are associated with development and establishing cell identity.[5]

Nomenclature

H3K4me3 indicates trimethylation of lysine 4 on histone H3 protein subunit:

| Abbr. | Meaning |

| H3 | H3 family of histones |

| K | standard abbreviation for lysine |

| 4 | position of amino acid residue

(counting from N-terminus) |

| me | methyl group |

| 3 | number of methyl groups added |

Lysine methylation

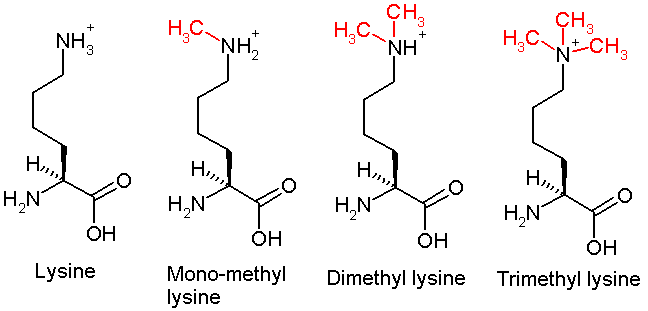

This diagram shows the progressive methylation of a lysine residue. The tri-methylation denotes the methylation present in H3K4me3.

The H3K4me3 modification is created by a lysine-specific histone methyltransferase (HMT) transferring three methyl groups to histone H3.[6] H3K4me3 is methylated by methyltransferase complexes containing a protein WDR5, which contains the WD40 repeat protein motif.[7] WDR5 associates specifically with dimethylated H3K4 and allows further methylation by methyltransferases, allowing for the creation and readout of the H3K4me3 modification.[8] WDR5 activity has been shown to be required for developmental genes, like the Hox genes, that are regulated by histone methylation.[7]

Epigenetic marker

H3K4me3 is a commonly used histone modification. H3K4me3 is one of the least abundant histone modifications; however, it is highly enriched at active promoters near transcription start sites (TSS) [9] and positively correlated with transcription. H3K4me3 is used as a histone code or histone mark in epigenetic studies (usually identified through chromatin immunoprecipitation) to identify active gene promoters.

H3K4me3 promotes gene activation through the action of the NURF complex, a protein complex that acts through the PHD finger protein motif to remodel chromatin.[2] This makes the DNA in the chromatin accessible for transcription factors, allowing the genes to be transcribed and expressed in the cell.

Understanding histone modifications

The genomic DNA of eukaryotic cells is wrapped around special protein molecules known as Histones. The complexes formed by the looping of the DNA are known as Chromatin. The basic structural unit of chromatin is the Nucleosome: this consists of the core octamer of histones (H2A, H2B, H3 and H4) as well as a linker histone and about 180 base pairs of DNA. These core histones are rich in lysine and arginine residues. The carboxyl (C) terminal end of these histones contribute to histone-histone interactions, as well as histone-DNA interactions. The amino (N) terminal charged tails are the site of the post-translational modifications, such as the one seen in H3K4me1.[10][11]

Role in stem cells and embryogenesis

Regulation of gene expression through H3K4me3 plays a significant role in stem cell fate determination and early embryo development. Pluripotent cells have distinctive patterns of methylation that can be identified through ChIP-seq. This is important in the development of induced pluripotent stem cells. A way of finding indicators of successful pluripotent induction is through comparing the epigenetic pattern to that of embryonic stem cells.[12]

In bivalent chromatin, H3K4me3 is co-localized with the repressive modification H3K27me3 to control gene regulation.[13] H3K4me3 in embryonic cells is part of a bivalent chromatin system, in which regions of DNA are simultaneously marked with activating and repressing histone methylations.[13] This is believed to allow for a flexible system of gene expression, in which genes are primarily repressed, but may be expressed quickly due to H3K4me3 as the cell progresses through development.[4] These regions tend to coincide with transcription factor genes expressed at low levels.[4] Some of these factors, such as the Hox genes, are essential for control development and cellular differentiation during embryogenesis.[2][4]

DNA repair

H3K4me3 is present at sites of DNA double-strand breaks where it promotes repair by the non-homologous end joining pathway.[14] It has been implicated that the binding of H3K4me3 is necessary for the function of genes such as inhibitor of growth protein 1 (ING1), which act as a tumor suppressors and enact DNA repair mechanisms.[15]

When DNA damage occurs, DNA damage signalling and repair begins as a result of the modification of histones within the chromatin. Mechanistically, the demethylation of H3K4me3 is used required for specific protein binding and recruitment to DNA damage[16]

Epigenetic implications

The post-translational modification of histone tails by either histone modifying complexes or chromatin remodelling complexes are interpreted by the cell and lead to complex, combinatorial transcriptional output. It is thought that a Histone code dictates the expression of genes by a complex interaction between the histones in a particular region.[17] The current understanding and interpretation of histones comes from two large scale projects: ENCODE and the Epigenomic roadmap.[18] The purpose of the epigenomic study was to investigate epigenetic changes across the entire genome. This led to chromatin states which define genomic regions by grouping the interactions of different proteins and/or histone modifications together. Chromatin states were investigated in Drosophila cells by looking at the binding location of proteins in the genome. Use of ChIP-sequencing revealed regions in the genome characterised by different banding.[19] Different developmental stages were profiled in Drosophila as well, an emphasis was placed on histone modification relevance.[20] A look in to the data obtained led to the definition of chromatin states based on histone modifications.[21] Certain modifications were mapped and enrichment was seen to localize in certain genomic regions. Five core histone modifications were found with each respective one being linked to various cell functions.

- H3K4me1-primed enhancers

- H3K4me3-promoters

- H3K36me3-gene bodies

- H3K27me3-polycomb repression

- H3K9me3-heterochromatin

The human genome was annotated with chromatin states. These annotated states can be used as new ways to annotate a genome independently of the underlying genome sequence. This independence from the DNA sequence enforces the epigenetic nature of histone modifications. Chromatin states are also useful in identifying regulatory elements that have no defined sequence, such as enhancers. This additional level of annotation allows for a deeper understanding of cell specific gene regulation.[22]

Methods

The histone mark H3K4me3 can be detected in a variety of ways:

1. Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-sequencing) measures the amount of DNA enrichment once bound to a targeted protein and immunoprecipitated. It results in good optimization and is used in vivo to reveal DNA-protein binding occurring in cells. ChIP-Seq can be used to identify and quantify various DNA fragments for different histone modifications along a genomic region.[23]

2. Micrococcal nuclease sequencing (MNase-seq) is used to investigate regions that are bound by well positioned nucleosomes. Use of the micrococcal nuclease enzyme is employed to identify nucleosome positioning. Well positioned nucleosomes are seen to have enrichment of sequences.[24]

3. Assay for transposase accessible chromatin sequencing (ATAC-seq) is used to look in to regions that are nucleosome free (open chromatin). It uses hyperactive Tn5 transposon to highlight nucleosome localisation.[25][26][27]

See also

References

- ↑ "Histone lysine methylation: a signature for chromatin function". Trends in Genetics 19 (11): 629–39. November 2003. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2003.09.007. PMID 14585615.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "A PHD finger of NURF couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with chromatin remodelling". Nature 442 (7098): 86–90. July 2006. doi:10.1038/nature04815. PMID 16728976. Bibcode: 2006Natur.442...86W.

- ↑ "Methylation of histone H3 K4 mediates association of the Isw1p ATPase with chromatin". Molecular Cell 12 (5): 1325–32. November 2003. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00438-6. PMID 14636589.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells". Cell 125 (2): 315–26. April 2006. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. PMID 16630819.

- ↑ "A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells". Cell 125 (2): 315–26. April 2006. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. PMID 16630819.

- ↑ "Histone methyltransferases direct different degrees of methylation to define distinct chromatin domains". Molecular Cell 12 (6): 1591–8. December 2003. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00479-9. PMID 14690610.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "WDR5 associates with histone H3 methylated at K4 and is essential for H3 K4 methylation and vertebrate development". Cell 121 (6): 859–72. June 2005. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.036. PMID 15960974.

- ↑ "Histone H3 recognition and presentation by the WDR5 module of the MLL1 complex". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 13 (8): 704–12. August 2006. doi:10.1038/nsmb1119. PMID 16829959.

- ↑ "Distinct localization of histone H3 acetylation and H3-K4 methylation to the transcription start sites in the human genome". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 (19): 7357–62. May 2004. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401866101. PMID 15123803. Bibcode: 2004PNAS..101.7357L.

- ↑ "Multivalent engagement of chromatin modifications by linked binding modules". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 8 (12): 983–94. December 2007. doi:10.1038/nrm2298. PMID 18037899.

- ↑ "Chromatin modifications and their function". Cell 128 (4): 693–705. February 2007. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. PMID 17320507.

- ↑ "New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells". Nature 448 (7150): 196–9. July 2007. doi:10.1038/nature05972. PMID 17597760. Bibcode: 2007Natur.448..196T.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Bivalent histone modifications in early embryogenesis". Current Opinion in Cell Biology 24 (3): 374–86. June 2012. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2012.03.009. PMID 22513113.

- ↑ "Histone methylation in DNA repair and clinical practice: new findings during the past 5-years". Journal of Cancer 9 (12): 2072–2081. 2018. doi:10.7150/jca.23427. PMID 29937925.

- ↑ "Histone H3K4me3 binding is required for the DNA repair and apoptotic activities of ING1 tumor suppressor". Journal of Molecular Biology 380 (2): 303–12. July 2008. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.061. PMID 18533182.

- ↑ "Histone demethylase KDM5A regulates the ZMYND8-NuRD chromatin remodeler to promote DNA repair". The Journal of Cell Biology 216 (7): 1959–1974. July 2017. doi:10.1083/jcb.201611135. PMID 28572115.

- ↑ "Translating the histone code". Science 293 (5532): 1074–80. August 2001. doi:10.1126/science.1063127. PMID 11498575.

- ↑ "Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project". Nature 447 (7146): 799–816. June 2007. doi:10.1038/nature05874. PMID 17571346. Bibcode: 2007Natur.447..799B.

- ↑ "Systematic protein location mapping reveals five principal chromatin types in Drosophila cells". Cell 143 (2): 212–24. October 2010. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.009. PMID 20888037.

- ↑ "Identification of functional elements and regulatory circuits by Drosophila modENCODE". Science 330 (6012): 1787–97. December 2010. doi:10.1126/science.1198374. PMID 21177974. Bibcode: 2010Sci...330.1787R.

- ↑ "Comprehensive analysis of the chromatin landscape in Drosophila melanogaster". Nature 471 (7339): 480–5. March 2011. doi:10.1038/nature09725. PMID 21179089. Bibcode: 2011Natur.471..480K.

- ↑ "Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes". Nature 518 (7539): 317–30. February 2015. doi:10.1038/nature14248. PMID 25693563. Bibcode: 2015Natur.518..317..

- ↑ "Whole-Genome Chromatin IP Sequencing (ChIP-Seq)". https://www.illumina.com/Documents/products/datasheets/datasheet_chip_sequence.pdf.

- ↑ "MAINE-Seq/Mnase-Seq". https://www.illumina.com/science/sequencing-method-explorer/kits-and-arrays/maine-seq-mnase-seq-nucleo-seq.html?langsel=/us/.

- ↑ "ATAC-seq: A Method for Assaying Chromatin Accessibility Genome-Wide". Current Protocols in Molecular Biology 109: 21.29.1–21.29.9. January 2015. doi:10.1002/0471142727.mb2129s109. ISBN 9780471142720. PMID 25559105.

- ↑ "Structured nucleosome fingerprints enable high-resolution mapping of chromatin architecture within regulatory regions". Genome Research 25 (11): 1757–70. November 2015. doi:10.1101/gr.192294.115. PMID 26314830.

- ↑ "DNase-seq: a high-resolution technique for mapping active gene regulatory elements across the genome from mammalian cells". Cold Spring Harbor Protocols 2010 (2): pdb.prot5384. February 2010. doi:10.1101/pdb.prot5384. PMID 20150147.

|