Biology:Hadropithecus

| Hadropithecus Temporal range: Pleistocene-Holocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

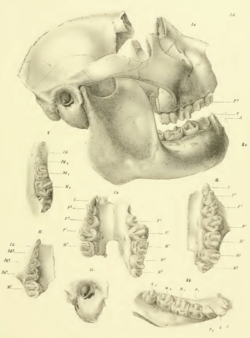

| Hadropoithecus stenognathus skull and mandible elements | |

Extinct (444–772)

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Animalia |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Chordata |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Mammalia |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Primates |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Strepsirrhini |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | †Archaeolemuridae |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | †Hadropithecus Lorenz von Liburnau, 1899[2] |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | <div style="display:inline" class="script error: no such module "taxobox ranks".">†H. stenognathus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Hadropithecus stenognathus Lorenz von Liburnau, 1899[1]

| |

| Synonyms[3][4] | |

|

Pithecodon sikorae Lorenz von Liburnau, 1900 | |

Hadropithecus is a medium-sized, extinct genus of lemur, or strepsirrhine primate, from Madagascar that includes a single species, Hadropithecus stenognathus. Due to its rarity and lack of sufficient skeletal remains, it is one of the least understood of the extinct lemurs. Both it and Archaeolemur are collectively known as "monkey lemurs" or "baboon lemurs" due to body plans and dentition that suggest a terrestrial lifestyle and a diet similar to that of modern baboons. Hadropithecus had extended molars and a short, powerful jaw, suggesting that it was both a grazer and a seed predator.

The monkey lemurs are considered to be most closely related to the living indriids and the recently extinct sloth lemurs, although recent finds had caused some dispute over a possible closer relation to living lemurids. Genetic tests, however, have reaffirmed the previously presumed relationship. Hadropithecus lived in open habitat in the Central Plateau, South, and Southwest regions of Madagascar. It is known only from subfossil or recent remains and is considered to be a modern form of Malagasy lemur. It died out around 444–772 CE, shortly after the arrival of humans on the island.

Etymology

The common names that Hadropithecus shares with Archaeolemur, "monkey lemurs" and "baboon lemurs", come from their dental and locomotor adaptations, which resemble that of modern African baboons.[5][6] The genus Hadropithecus is derived from the Greek words αδρος, hadros, meaning "stout" or "large", and πίθηκος, pithekos, meaning "ape". The species name derives from the Greek root στενο-, steno-, meaning "narrow", and γναθος, gnathos, meaning "jaw" or "mouth".[2]

Classification and phylogeny

Hadropithecus stenognathus is classified as the sole member of the genus Hadropithecus and belongs to the family Archaeolemuridae. This family in turn belongs to the infraorder Lemuriformes, which includes all the Malagasy lemurs.[1] The species was formally described in 1899 from a mandible (lower jaw) found at Andrahomana cave in southeastern Madagascar by paleontologist Ludwig Lorenz von Liburnau, who thought it represented an ape.[7] A year later, Lorenz von Liburnau also described Pithecodon sikorae based on photographs of a skull, which upon further review turned out to be a juvenile version of Hadropithecus stenognathus. In a publication from 1902, he declared that Hadrophithecus stenognathus was not an ape, but a lemur.[3] Over 100 years later, the rarity of its skeletal remains has made this species one of the least understood species of subfossil lemur.[4]

| Hadropithecus placement within the lemur phylogeny[8][9][10] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Based on similarities in their skull and teeth, it was later thought that monkey lemurs (Hadropithecus and Archaeolemur) were a sister group to the living indriids and the recently extinct sloth lemurs (family Palaeopropithecidae).[11][12] However, there was some debate over whether the monkey lemurs or the sloth lemurs were more closely related to today's indriids. The monkey lemurs had skulls that more closely resembled the indriids, but their teeth were very specialized and unlike those of the indriids. The sloth lemurs, on the other hand, had teeth like the indriids, but very specialized skulls. The matter was settled with the discovery of new skeletons of Babakotia and Mesopropithecus, two genera of sloth lemur, both of which had indriid-like skulls and teeth.[11] More recently, postcranial remains of Hadropithecus found in the early 2000s prompted the suggestion that the monkey lemurs were more closely related to the lemurids.[13] However, DNA sequencing has reaffirmed the sister group status of the monkey lemurs to indriids and sloth lemurs.[9]

Anatomy and physiology

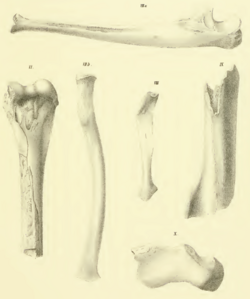

Hadropithecus stenognathus has been estimated to have weighed between 27 and 35 kg (60 and 77 lb) and to have been roughly as large as Archaeolemur, although more gracile.[1][5] Newer subfossil finds, however, suggest that Hadropithecus may have been more robust, and more like a gorilla than a baboon.[14] It may also have been less agile than Old World monkeys.[4] Both lemurs were quadrupedal (walked on four legs).[5] There is no evidence of cursoriality (adaptations specifically for running) in either species,[14] and although Hadropithecus could have climbed trees, it lacked adaptations for leaping or suspension.[4]

Although fewer postcranial remains have been discovered for Hadropithecus than for Archaeolemur, what has been found indicates that both were adapted for a terrestrial or semi-terrestrial lifestyle,[1][5][6][12] an unusual trait for lemurs. Both genera had short limbs and a powerful build.[11] Due to its specialized dentition and likely diet, Hadropithecus is thought to have been the more terrestrial of the two,[12] since Archaeolemur may have sent more time foraging and sleeping in the trees.[5] Both genera also have shortened hands and feet, an adaptation for walking on the ground.[11]

The face of Hadropithecus was shortened and adapted to heavy stress from chewing. The monkey lemurs had highly specialized teeth, but Hadropithecus went further by specializing in strong grinding.[15] It had expanded molars that wore down quickly,[11] much like those of ungulates,[1] and its posterior premolars acted like molars to extend the grinding surface.[11] It also had a robust mandible to facilitate crushing hard objects.[15] Even the strepsirrhine toothcomb was reduced in this species.[1][6][11] Its dental formula was 2.1.3.31.1.3.3 × 2 = 34[11]

The skulls of both Hadropithecus and Archaeolemur indicate that monkey lemurs had relatively large brains compared to the other subfossil lemurs, with Hadropithecus having an estimated endocranial volume of 115 ml.[4]

Ecology

Like all other lemurs, Hadropithecus was endemic to Madagascar. Because it died out only recently and is only known from subfossil remains, it is considered to be a modern form of Malagasy lemur.[6] It once ranged across the Central Plateau, South, and Southwest regions of Madagascar.[1][6] Within its original range, there were few other lemurs to overlap its ecological niche, and it has been shown to be the only subfossil lemur to consume both C3 and C4 (or CAM) plants, an indication that it lived in more open habitats and had a varied diet.[5][14] Its physiology and dentition suggest that it may have been much like the Gelada Baboon in locomotion and diet,[1][6][11] acting as a manual grazer (picking grass with the hands) since its teeth were well-adapted for grinding either grass or seeds.[6][12] Microwear patterns on its teeth, as well as its overly large molars, indicate it processed hard objects like nuts or seeds, making it a seed predator.[14][15] More recent microwear analysis suggests differences between Gelada Baboons and Hadropithecus, indicating that this extinct lemur may not have been a grazer, but strictly a hard object processor.[4]

Extinction

Because of the low number of subfossil finds, Hadropithecus is thought to have been rare,[12] and it died out sooner than its sister taxon, Archaeolemur.[5] Both disappeared shortly after the arrival of humans to the island, but being a large, specialized, terrestrial grazer, Hadropithecus would have faced more pressure from domestic livestock, introduced pigs, and spreading human populations than its more generalized cousin.[1] The last known record was radiocarbon dated to around 444–772 CE.[5]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Nowak, R.M. (1999). "Family Archaeolemuridae: Baboon Lemurs". Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8. https://archive.org/details/walkersmammalsof0002nowa.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Palmer, T. (1904). "Index generum mammalium: a list of the genera and families of mammals". North American Fauna 23: 1–984. doi:10.3996/nafa.23.0001. https://books.google.com/books?id=WdnPAAAAMAAJ. pp. 80–81, 539, 645, 648.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Lorenz von Liburnau, L. (1902). "Über Hadropithecus stenognathus Lz., nebst Bemerkungen zu einigen anderen ausgestorbenen Primaten von Madagaskar". Denkschriften der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Klasse, Wien 72: 243–254. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/31611#315.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Ryan, T.M.; Burney, D.A.; Godfrey, L.R.; Göhlich, U.B.; Jungers, W.L.; Vasey, N.; Ramilisonina; Walker, A. et al. (2008). "A reconstruction of the Vienna skull of Hadropithecus stenognathus". PNAS 105 (31): 10699–10702. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805195105. PMID 18663217. PMC 2488384. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..10510699R. http://www.pnas.org/content/105/31/10699.full.pdf. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Template:LoM2

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Sussman, R.W. (2003). "Chapter 4: The Nocturnal Lemuriformes". Primate Ecology and Social Structure. Pearson Custom Publishing. pp. 107–148. ISBN 978-0-536-74363-3.

- ↑ Lorenz von Liburnau, L. (1899). "Herr Custor Dr. Ludwig v. Lorenz berichtet über einen fossilen Anthropoiden von Madagascar". Anzeigen der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Classe, Wien 27: 255–257. https://books.google.com/books?id=xkQUAAAAYAAJ&q=Hadropithecus&pg=PA255.

- ↑ Horvath, J. (2008). "Development and application of a phylogenomic toolkit: Resolving the evolutionary history of Madagascar's lemurs". Genome Research 18 (3): 489–99. doi:10.1101/gr.7265208. PMID 18245770. PMC 2259113. http://www.biology.duke.edu/yoderlab/reprints/2008Horvath_etalGR.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Orlando, L.; Calvignac, S.; Schnebelen, C.; Douady, C.J.; Godfrey, L.R.; Hänni, C. (2008). "DNA from extinct giant lemurs links archaeolemurids to extant indriids". BMC Evolutionary Biology 8: 121. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-121. PMID 18442367.

- ↑ Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L. (2003). "Subfossil Lemurs". in Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. The Natural History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1247–1252. ISBN 978-0-226-30306-2.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Template:LoM1

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Simons, E.L. (1997). "Chapter 6: Lemurs: Old and New". in Goodman, S.M.; Patterson, B.D. Natural Change and Human Impact in Madagascar. Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 142–166. ISBN 978-1-56098-682-9.

- ↑ Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Burney, D.A.; Vasey, N.; Ramilisonina, S.J.; Wheeler, W.; Lemelin, P.; Shapiro, L.J. et al. (2006). "New discoveries of skeletal elements of Hadropithecus stenognathus from Andrahomana Cave, southeastern Madagascar". Journal of Human Evolution 51 (4): 395–410. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.04.012. PMID 16911817.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Schwartz, G.T. (2006). "Chapter 3: Ecology and Extinction of Madagascar's Subfossil Lemurs". in Gould, L.; Sauther, M.L. Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. Springer. pp. 41–64. ISBN 978-0-387-34585-7. https://archive.org/details/lemursecologyada00goul.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Reed, K.E.; Simons, E.L.; Chatrath, P.S. (1997). "Chapter 8: Subfossil Lemurs". in Goodman, S.M.; Patterson, B.D.. Natural Change and Human Impact in Madagascar. Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 218–256. ISBN 978-1-56098-682-9.

Wikidata ☰ Q291849 entry

|