Biology:Inland free-tailed bat

| Inland free-tailed bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | M. petersi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Mormopterus petersi Leche, 1884

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The inland free-tailed bat (Mormopterus petersi) is a species of bat found in Australia . It is notable for being able to tolerate the most extreme body temperature range of any known mammal.

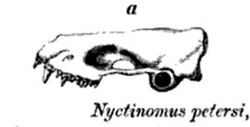

Taxonomy and etymology

It was initially described in 1884 by Swedish zoologist Dr. Wilhelm Leche.[2] Leche had acquired the specimens used in his description from Gustav Schneider, a Swiss natural history dealer.[3] Leche initially placed it in the now-defunct genus Nyctinomus with the species name petersi.[2] While Leche did not state the eponym for the species name "petersi", it is possible that it was named in honor of Wilhelm Peters, a German naturalist who described several species and genera of bats and had passed away a year prior to Leche's publication in 1884. In 1906, Oldfield Thomas published a paper in which he considered N. petersi as synonymous with the southern free-tailed bat.[4] This status was largely maintained until 2014, when a study examining the morphology and genetics of the bats of Australia showed that it was distinct enough to be considered a full species.[5]

Description

In describing the species, Leche noted that it is similar in appearance to the east-coast free-tailed bat, Mormopterus norfolkensis. He wrote that it differs in its flat, compressed skull. It is a small species of bat, with a head and body length of 57 mm (2.2 in), a tail length of 33 mm (1.3 in), and a forearm length of 34 mm (1.3 in). The tail extends approximately 12 mm (0.47 in) past the edge of the uropatagium. Its tragus is tiny, at only 3 mm (0.12 in) long.[2] It weighs 7.5–11.8 g (0.26–0.42 oz).[5]

Biology

The inland free-tailed bat is nocturnal, roosting in sheltered places during the day such as tree cavities or under metal roofs. Females have one breeding season annually, and give birth in November or December. The litter size is generally one individual, with the young called a "pup."[1] This species of bat can tolerate the most extreme range of body temperatures of any known mammal. Its body temperature has been recorded as low as 3.3 °C (37.9 °F) and as high as 45.8 °C (114.4 °F).[6] This upper limit even exceeds recorded maximum body temperatures of camels. These bats can survive these otherwise lethal extremes by using torpor, which is a physiological adaptation.[6]

Conservation

This bat is currently listed as least concern by the IUCN—its lowest conservation priority. It meets the criteria for this assessment because it has a large geographic range; it tolerates a variety of habitats; its population size is thought to be large; and it is documented regularly throughout its range. Its population may exceed one million individuals, although this number may be declining.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Reardon, T.; Lumsden, L. (2017). "Mormopterus petersi". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T71534469A71534471. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T71534469A71534471.en. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Leche, W. (1884). "On some species of Chiroptera from Australia". Journal of Zoology 52 (1): 49–54. https://books.google.com/books?id=BvAKAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA49#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ Beolens, B.; Watkins, M.; Grayson, M. (2013). The eponym dictionary of amphibians. Pelagic Publishing. p. 193. ISBN 9781907807428.

- ↑ Thomas, O. (1906). "On mammals collected in south-west Australia for Mr. WE Balston". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 76: 468–478. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/31208179.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Reardon, T. B.; McKenzie, N. L.; Cooper, S. J. B.; Appleton, B.; Carthew, S.; Adams, M. (2014). "A molecular and morphological investigation of species boundaries and phylogenetic relationships in Australian free-tailed bats Mormopterus (Chiroptera: Molossidae)". Australian Journal of Zoology 62 (2): 109–136. doi:10.1071/ZO13082.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Nowack, J.; Stawski, C.; Geiser, F. (2017). "More functions of torpor and their roles in a changing world". Journal of Comparative Physiology B 187 (5-6): 889–897. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00360-017-1100-y.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q18419330 entry