Biology:Banded hare-wallaby

| Banded hare-wallaby | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Macropodidae |

| Subfamily: | Lagostrophinae |

| Genus: | Lagostrophus Thomas, 1887[3] |

| Species: | L. fasciatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lagostrophus fasciatus (Péron & Lesueur, 1807)

| |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Banded hare-wallaby range (red — native, pink — reintroduced) | |

The banded hare-wallaby, mernine, or munning (Lagostrophus fasciatus) is a marsupial currently found on the islands of Bernier and Dorre off western Australia . Reintroduced populations have recently been established on islands and fenced mainland sites, including Faure Island[4] and Wadderin Sanctuary near Narembeen in the central wheatbelt.[citation needed]

Taxonomy

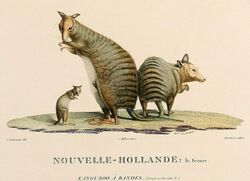

The description of the species was published in the 1807 report of a French expedition to Australia. The authors, zoologist François Péron and illustrator Charles Lesueur, described a specimen collected at Bernier Island during their visit to the region in 1801, naming the new species as Kangurus fasciatus.[5]

Evidence suggested that the mernine was the only living member of the sthenurine subfamily,[6] and a recent osteology-based phylogeny of macropodids found that the banded hare-wallaby was indeed a bastion of an ancient lineage, agreeing with other (molecular) appraisals of the evolutionary history of L. fasciatus.[7] However, the authors' analysis did not support the placement of the mernine within Sthenurinae, but suggest it belongs to a plesiomorphic clade which branched off from other macropodids in the early Miocene and founded the new subfamily Lagostrophinae.[7] Recent analysis of mtDNA extracted from fossils of the sthenurine Simosthenurus supports this conclusion.[8] This new subfamily includes the banded hare-wallaby and the fossil genus Troposodon.[7]

Description

The average banded hare-wallaby weighs 1.7 kg, females weigh more than the males. It measures about 800 mm from the head to the end of the tail, with the tail almost the same length (averaging 375 mm) as the body. It has a short nose; its long, grey fur is speckled with yellow and silver and fades into a light grey on the underbelly. No colour variation is seen on the face or head, and its colouring is solid grey. Dark, horizontal stripes of fur start at the middle of the back and stop at the base of the tail.

Behavior

The banded hare-wallaby is nocturnal and tends to live in groups at nesting sites; this species is quite social. Nesting occurs in thickets under very dense brush. This macropod prefers to live in Acacia ligulata scrub. Males are extremely aggressive.

Distribution

The species was once found on the mainland, in the southwest of Western Australia and South Australia, but its only surviving natural populations are now restricted to Bernier Island and Dorre Island off Western Australia.[9] The species has been successfully reintroduced to Faure Island[4] and Dirk Hartog Island[10] in Shark Bay, and to a large fenced reserve at Mount Gibson Sanctuary[11] in Western Australia.

Although the banded hare-wallaby was once found across the south-western portion of Australia, it is believed to have been extinct on the mainland since 1963, and the last recorded evidence of the banded hare-wallaby on the Australian mainland was in 1906. The devastation of the species possibly can be attributed to the loss of habitat to the clearing of vegetation, the loss of food (due to competition with other animals), and predators.

Diversity

Two subspecies are recognized:[9] L. f. fasciatus and L. f. baudinettei.

Feeding

This diprotodontian is a vegetarian and receives most of its water from food. It prefers to eat various grasses, fruit, and other vegetation. Male aggression is usually brought out in competition for food with other males and is very rarely expressed toward females.

Reproduction

Mating season starts in December and ends in September. The banded hare-wallaby reaches maturity at one year of age, breeding usually starts in the second year. Gestation appears to last several months and mothers generally raise one young each year, although females may produce two young per year. Young remain in their mother's pouch for six months and continue to be weaned for another three months. In situations where a mother's young dies, some mothers have an extra embryo to possibly rear another.

References

- ↑ Burbidge, A.A.; Woinarski, J. (2016). "Lagostrophus fasciatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T11171A21955969. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T11171A21955969.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/11171/21955969. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ↑ "Appendices | CITES". https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php.

- ↑ Thomas, O. (1887). "On the wallaby commonly known as Lagorchestes fasciatus". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1886: 544–547. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/69488.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Faure Island" (in en-AU). https://www.australianwildlife.org/where-we-work/faure-island/.

- ↑ Péron, François; de Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses; Lesueur, Charles Alexandre; Petit, Nicolas Martin (1807). Voyage de découvertes aux terres australes, exécuté par ordre de Sa Majesté l'empereur et roi, sur les corvettes le Géographe, le Naturaliste, et la goëlette le Casuarina, pendant les années 1800, 1801, 1802, 1803 et 1804 ... . [Historique publié par dećret impérial, sous le ministère de M. de Champagny et Rédigé ... par M. F. Péron [et continué par M. Louis Freycinet] [Atlas par MM. Lesueur et Petit.]]. 1. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/156474.

- ↑ Flannery, T.F. (1983). "Revision in the subfamily Sthenurinae (Marsupialia: Macropodoidea) and the relationships of the species of Troposodon and Lagostrophus". Australian Mammalogy 6 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1071/AM83002.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Prideaux, G.J.; Warburton, N.M. (2010). "An osteology-based appraisal of the phylogeny and evolution of kangaroos and wallabies (Macropodidae: Marsupialia)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 159 (4): 954–87. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00607.x.

- ↑ Llamas, B.; Brotherton, P.; Mitchell, K.J.; Templeton, J.E.L.; Thomson, V.A.; Metcalf, J.L.; Armstrong, K.N.; Kasper, M. et al. (2014-12-18). "Late Pleistocene Australian marsupial DNA clarifies the affinities of extinct megafaunal kangaroos and wallabies". Molecular Biology and Evolution 32 (3): 574–584. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu338. PMID 25526902.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Diprotodontia". in Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=11000196.

- ↑ Digital, Seven West Media (2017-09-19). "Threatened hare-wallabies released as Dirk Hartog…" (in en). https://westtravelclub.com.au/stories/threatened-hare-wallabies-released-as-dirk-hartog-island-becomes-ark-for-native-species.

- ↑ "Shark Bay translocations a boost for threatened mammals at Faure Island and Mt Gibson" (in en-AU). 2018-11-10. https://www.australianwildlife.org/shark-bay-translocations-a-boost-for-threatened-mammals-at-faure-island-and-mt-gibson/.

External links

- Animal Info – Banded hare-wallaby

- "Lagostrophus Thomas, 1887". Atlas of Living Australia. https://bie.ala.org.au/species/https://biodiversity.org.au/afd/taxa/16cd0736-0f29-41cb-a37e-643a729e9264.

- australianfauna.com – Banded hare-wallaby

Wikidata ☰ Q670056 entry

|