Biology:Lasioglossum zephyrum

| Lasioglossum zephyrum | |

|---|---|

| |

| L. zephyrum (top) with a cuckoo wasp | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | L. zephyrum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lasioglossum zephyrum (Smith, 1853)[1]

| |

Lasioglossum zephyrum is a sweat bee of the family Halictidae, found in the U.S. and Canada. It is considered a primitively eusocial bee (meaning that they do not have a permanent division of labor within colonies),[2] although it may be facultatively solitary (i.e., displaying both solitary and eusocial behaviors).[1][3] The species nests in underground burrows and has been observed forcing open unbloomed flowers of species Xyris tennesseensis to extract the pollen, ensuring first and exclusive access.[4]

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The order Hymenoptera contains more eusocial species than any other order.[5] Eusociality has many origins and is present in many degrees within Hymenoptera, with L. zephyrum being one of the more primitive examples.[2][5] The genus Lasioglossum is predominantly eusocial, but has a high level of variation in sociality.[5] For instance, Lasioglossum zephyrum, as well as another species of this family of bees, Halictidae, Halictus ligatus, are known for their characteristic primitively eusocial behavior.This unique type of eusociality gives insight about the evolutionary background of eusociality of these species.[6] Six species within this genus have reverted to solitary life, social polymorphism, or parasitism.[5]

Description and identification

Lasioglossum zephyrum is characterized by its dark green metallic color, reddish abdomen, and a hairier face than most other species. Males are 6 to 7 millimeters long, slightly larger than females. Males are distinguished from females by their brighter green color and redder abdomens.[7] Since the castes vary along a spectrum, there is no definite way to distinguish a worker from a queen based on appearance alone.[8] However, queens can be identified by their behavior, pushing subordinates down in the nest and nudging them to inhibit their reproduction.[9]

Distribution and habitat

L. zephyrum has been found throughout the United States, in the months of March through October.[7][10] Nests are usually constructed in April along the south facing edges of streams, and are clustered in aggregations of up to 1,000 nests.[8][11] It nests in underground burrows that are typically constructed by young females. However, older females may also contribute to burrowing if their nests have been destroyed. These females excavate primarily at night, but activity has been reported throughout the day. Workers use their mandibles to loosen the soil, then carry it a short distance to be picked up by another bee. This soil is ultimately smoothed over the walls or used to fill evacuated old burrows. Females excavate cells and line them with a liquid produced in their enlarged Dufour's glands and secreted from the apex of the abdomen.[10]

Colony cycle

Lasioglossum zephyrum nests consist of less than 20 individuals.[10] During the spring, around April, new nests are established by one or more females.[8][10] Some of these nest may never gain more members, and the female will remain solitary. If they do expand, the colony will reach its maximum size of 10–20 around August.[3][10] Growth of the colony is gradual throughout the summer.[8] Inseminated young queens overwinter in their nests so that the cycle may be repeated.[3][8] However, overwintered queens are likely to die early on in the summer. After the death of an old queen, a new queen takes over within hours.[10] L. zephyrum colonies have a high mortality rate, especially when inhabited by a solitary bee lacking guards.[8][9]

Behavior

Dominance hierarchy

Roles within the hive are indirectly determined by age or physical differences, but direct determination is made by dominance interactions.[10] This type of hierarchy is very different from other species of bees, such as the Lasioglossum hemichalceum, which is characterized by its egalitarian behavior and lack of aggression. All female L. hemichalceum are able to reproduce and cooperate to raise their young.[12] Queens have been shown to back workers into the depths of the burrows, preventing them from foraging and growing larger queen sized ovaries.[9] The tendency to display these behaviors is not influenced by the genetic relatedness of the subordinate bee, but it does decrease with time. In general, within colonies more closely related, there tends to be less aggression between bees.[13] When the queen dies, another worker takes her place and begins reproduction.[9] Among females, queens are at the top of the dominance hierarchy with their developed ovaries. Second are the guards, with some ovarian development. Foragers are the most subordinate group.[13]

Division of labor

Young females are responsible for constructing the nest. As adults, Lasioglossum zephyrum females become either mated egg-layers or workers who forage, guard, and make cells.[10] In a typical Lasioglossum zephyrum colony, the oldest females tend to be mated queens. However, among similarly aged bees, the largest is generally the queen.[3] The queen does not collect pollen or construct cells after her first batch of workers has hatched.[14] Queens and workers are not very physically distinct, since bee size varies on a continuum.[3]

Male behavior

Males are not considered productive members of the nest since they do not remain in their home nests. Instead, they form swarms around clusters of nests as early as 2 days after hatching.[8][15][16] Early in the spring, the males are solitary or clustered in small groups, but by late summer they gather in swarms of thousands of bees. Within these swarms there are head-on collisions between bees as they search for females and flowers.[16] While foraging, L. zephyrum searches for flowers, sometimes even forcing them open in order to get first access to the pollen.[4] Males have been seen landing on small pebbles and small objects as if they were females and have been observed mating as young as 4 days old up until death. In the laboratory, males were observed to have specific patrolling routes, flying between specific objects in sequence. They sleep in holes, plants, or abandoned burrows, solitarily or in small groups.[16]

Reproductive suppression

Most queens will mate during their lifetimes, but asome workers may mate as well since they are physiologically capable.[3] In fact, about 18% of workers mate successfully between the months of June and August. When a queen is present, workers are not typically receptive to mating.[15] Females have been shown to partake in egg cannibalism, eating the eggs of nest mates, thus inhibiting their reproduction,[10] as well as the aggressive behaivors described in the dominance hierarchy subsection.

Mating behavior

Mating tends to take place near the nest's entrance, where the males typically fly.[15] Males will pursue females on land, but not in the air, and have been shown to aggressively attack females at the nest's entrance. Males will approach and occasionally grasp bees of other species, but no heterospecific matings have been documented. Females secrete an odor that functions as an aphrodisiac and a sex attractant. This odor is produced by female virgins between the ages of 2 and 8 days. The courtship period is short, and copulation occurs with the male above the female. In the field, L. zephyrum has been seen to copulate for 10–42 seconds. Most of the males' attempts at mating were met with resistance, but the females tend to remain relatively motionless during copulation. Many females are successful at preventing unwanted matings, suggesting that they have at least some control over their choice of mate. As many as four males have been observed stacked on top of a copulating male in attempt to mate with that female.[17]

Communication and recognition

Individual bees can recognize their nest and nest mates by their odors, which helps to prevent parasitism by unrelated L. zephyrum as well as other species.[18][19] This recognition has been documented in both males and females. Males can identify individual females by their unique odors and learn to avoid females who are unreceptive to mating.[19] L. zephyrum has also been shown to leave foreign nests even without being attacked, which supports the theory that they use odors to identify their home nests.[18]

Kin selection

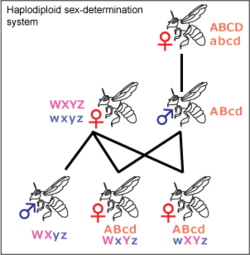

In Hymenoptera species, like Lasioglossum zephyrum, females are diploid and males are typically haploid, in a system called haplodiploidy. However, in inbred L. zephyrum populations, and also in other hymenopteran species, diploid males have been discovered.[20] Hymenopteran workers are expected to be related by a coefficient of 3/4, assuming the queen only mates only once.[11][15] However, in those nests studied, the relatedness coefficient was found to be lower, around 0.7. This could be explained by the insemination of multiple queens. With a relationship this high, significant altruism is likely.[11] The workers share only half of their genes with the queen, so they have more genes in common with their sisters. Since workers are more closely related to their sisters than their own offspring, whose relationship coefficient would be 0.5, kin selection has been proposed as an additional reason why workers mate so infrequently. They can pass down more genes through sisters than the same number of direct offspring.[15] Nests have been shown to be more genetically similar to nests in close proximity.[11]

Kin recognition and discrimination

Once an individual has learned the odor of its kin, it can successfully identify kin it has never met, since odors are genetically determined. Additionally, it can determine whether this relative is a close or distant relative.[21] While learning does play a role in kin recognition, the genetic differences in odor are thought to be more critical in kin recognition. Kin recognition is beneficial for defense of the entire nest, as well as at the individual level. Individuals benefit by contributing only to the fitness of their own related nest mates.[18]

Diet

Adult Lasioglossun zephyrum feed their larva pollen from surrounding plants. Since they forage at a variety of different flowers, they collect multiple types of pollen. Some types are more protein dense than others, but the adults do not compensate for the difference in pollen quality. All offspring receive the same amount of pollen, which results in offspring of different sizes. Size is an advantage for females because it gives them a better chance of becoming a queen. They also tend to produce more eggs of better quality, and greater size increases the chance that a female survives the winter. Larger males are better able to defend territories and compete for mates. Size is also a factor for both species in regards to flight. Larger body size leads to an increased body temperature and the ability to fly sooner in the season and with greater frequency.[22]

Interactions

Parasites

L. zephyrum has been parasitized by diverse organisms including bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and other species of hymenoptera. Nematodes have been found in the abdominal cavities of L. zephyrum females, and have led to a reduction in ovarian development. Parasites that attack in the spring during nest founding tend to be most successful. If threatened, the bee may try to attack it or decapitate the intruder. Guard bees are often responsible for the protection of the nest and will send one member to attack while the others block the entrance with their abdomens.

Nests containing only infected females are in danger of dying out. While infected bees are able to excavate burrows, they are less active than healthy bees and do not collect pollen to make cells.

Gregarine protozoa have been found generally in older specimens of L. zephyrum. It is thought that once a bee is infected, it takes time for the spores to fully develop. These parasites have only been found in females, although it is unclear why males remain unaffected.[8]

Commensalisms

Bees of the species Paralictus cephalicus has been seen to coexist within the burrows of some L. zephyrum populations.[8]

Aggressive interactions

The mutillid Pseudomethoca frigida is known to engage in aggressive fights with female L. zephyrum. Instead of stinging its opponent, L. zephyrum attempts to decapitate it. The mutillid retreats, unable to defend itself.[8]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Species Lasioglossum zephyrum". BugGuide. http://bugguide.net/node/view/179479. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Batra, S. W. T. 1966. The life cycle and behavior of the primitively social bee Lasioglossum zephyrum (Halictidae). Univ. Kansas Sci. Bull. 46:359–423.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Interactions in Colonies of Primitively Social Bees: Artificial Colonies of Lasioglossum zephyrum. PNAS. Retrieved 08-27-2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wall, M. A.; Teem, A. P.; Boyd, R. S. (Mar 2002). "Floral Manipulation by Lassioglosssum zephyrum (Hymenoptera: Halictidae) Ensures First Access to Floral Rewards by Initiating Premature Anthesis of Xyris tennesseenis (Xyridaceae) Flowers". Florida Entomologist 85 (1): 290–291. doi:10.1653/0015-4040(2002)085[0290:fmblzh2.0.co;2]. http://www.bioone.org/doi/pdf/10.1653/0015-4040(2002)085%5B0290%3AFMBLZH%5D2.0.CO%3B2. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Danforth, Bryan N.; Conway, Lindsay; Ji, Shuqing (2003-02-01). "Phylogeny of Eusocial Lasioglossum Reveals Multiple Losses of Eusociality within a Primitively Eusocial Clade of Bees (Hymenoptera: Halictidae)". Systematic Biology 52 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1080/10635150390132687. ISSN 1063-5157. PMID 12554437. http://sysbio.oxfordjournals.org/content/52/1/23.

- ↑ Pabalan, N., K.G. Davey, and L. Packer. "Escalation of Aggressive Interactions During Staged Encounters in Halictus ligatus Say (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), with a Comparison of Circle Tube Behaviors with Other Halictine Species'." Journal of Insect Behavior 13.5 (2000): 627-650.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Discover Life". http://www.discoverlife.org/20/q?search=Lasioglossum+zephyrum. Retrieved September 19, 2015.http://www.discoverlife.org/20/q?search=Lasioglossum+zephyrum

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 Batra, Suzanne W. T. (1965-10-01). "Organisms Associated with Lasioglossum zephyrum (Hymenoptera: Halictidae)". Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 38 (4): 367–389.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Michener, Charles D.; Brothers, Denis J. (1974-03-01). "Were Workers of Eusocial Hymenoptera Initially Altruistic or Oppressed?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 71 (3): 671–674. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.3.671. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 16592144. PMC 388074. http://www.pnas.org/content/71/3/671.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 Batra, Suzanne W. T. (1964-06-01). "Behavior of the social bee,Lasioglossum zephyrum, within the nest (Hymenoptera: Halictidæ)". Insectes Sociaux 11 (2): 159–185. doi:10.1007/BF02222935. ISSN 0020-1812. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02222935.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Crozier, R. H.; Smith, B. H.; Crozier, Y. C. (1987-07-01). "Relatedness and Population Structure of the Primitively Eusocial Bee Lasioglossum zephyrum (Hymenoptera: Halictidae) in Kansas". Evolution 41 (4): 902–910. doi:10.2307/2408898.

- ↑ Kukuk, Penelope F. (1992-01-12). "Social Interactions and Familiarity in a Communal Halictine Bee Lasioglossum (Chilalictus) hemichalceum". Ethology 91 (4): 291–300. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1992.tb00870.x. ISSN 1439-0310. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1439-0310.1992.tb00870.x/abstract.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Smith, Brian H. (1987-02-01). "Effects of genealogical relationship and colony age on the dominance hierarchy in the primitively eusocial bee Lasioglossum zephyrum". Animal Behaviour 35 (1): 211–217. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(87)80226-9. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347287802269.

- ↑ Michener, Charles D.; Brothers, Denis J.; Kamm, Dwight R. (1971-04-01). "Interactions in Colonies of Primitively Social Bees: II, Some Queen-Worker Relations in Lasioglossum zephyrum". Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 44 (2): 276–279.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Greenberg, Les; Buckle, Gregory R. (1981-12-01). "Inhibition of worker mating by queens in a sweat bee,Lasioglossum zephyrum". Insectes Sociaux 28 (4): 347–352. doi:10.1007/BF02224192. ISSN 0020-1812. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02224192.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Mating Behavior in Halictine Bees (Hymenoptera: Halictidae): I, Patrolling and Age-Specific Behavior in Males on JSTOR".

- ↑ Barrows, Edward M. (1975-09-01). "Mating behavior in halictine bees (Hymenoptera: Halictidae): III. Copulatory behavior and olfactory communication". Insectes Sociaux 22 (3): 307–331. doi:10.1007/BF02223079. ISSN 0020-1812. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02223079.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Kukuk, Penelope F.; Breed, Michael D.; Sobti, Anita; Bell, William J. (1977-01-01). "The Contributions of Kinship and Conditioning to Nest Recognition and Colony Member Recognition in a Primitively Eusocial Bee, Lasioglossum zephyrum (Hymenoptera: Halictidae)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 2 (3): 319–327. doi:10.1007/bf00299743.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Wcislo, William T. (1987-03-01). "The role of learning in the mating biology of a sweat bee Lasioglossum zephyrum (Hymenoptera: Halictidae)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 20 (3): 179–185. doi:10.1007/BF00299731. ISSN 0340-5443. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00299731.

- ↑ Kukuk, Penelope F.; May, Bernie (1990-09-01). "Diploid Males in a Primitively Eusocial Bee, Lasioglossum (Dialictus) zephyrum (Hymenoptera: Halictidae)". Evolution 44 (6): 1522–1528. doi:10.2307/2409334.

- ↑ Greenberg, Les (1988-07-01). "Kin recognition in the sweat bee,Lasioglossum zephyrum". Behavior Genetics 18 (4): 425–438. doi:10.1007/BF01065512. ISSN 0001-8244. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01065512.

- ↑ Roulston, T'ai H.; Cane, James H. (2002-01-01). "The effect of pollen protein concentration on body size in the sweat bee Lasioglossum zephyrum (Hymenoptera: Apiformes)". Evolutionary Ecology 16 (1): 49–65. doi:10.1023/A:1016048526475. ISSN 0269-7653. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A%3A1016048526475.

External links

- http://bugguide.net/node/view/179479. Bugguide.net

Wikidata ☰ Q2204234 entry