Biology:Leucospermum conocarpodendron

| Leucospermum conocarpodendron | |

|---|---|

| |

| top subsp. conocarpodendron, bottom subsp. viridum | |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Genus: | Leucospermum |

| Species: | L. conocarpodendron

|

| Binomial name | |

| Leucospermum conocarpodendron (L.) H.Buek

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Leucospermum conocarpodendron is the largest species of the genus Leucospermum, reaching almost tree-like proportions of 5–6 m (16–20 ft) high with a firm trunk that is covered in a thick layer of cork that protects it from most fires. It has greyish or green narrow or broad inverted egg-shaped leaves with three to ten teeth near the tip and large yellow flowerheads, with firm, bent, yellow styles that stick far beyond the rest of the flower and give the impression of a pincushion. It is commonly known as the tree pincushion in English or goudsboom in Afrikaans. They naturally occur near Cape Town, South Africa.

Two subspecies are distinguished. L. conocarpodendron subsp. conocarpodendron, that has greyish leaves because they have a covering of felty hairs. L. conocarpodendron subsp. viridum, has green leaves that lack felty hairs. Flowers can be found between August and December.[2]

Description

L. conocarpodendron is an evergreen large shrub of 3–5 m (9.8–16.4 ft) high and 3–6 m (9.8–19.7 ft) in diameter with a rounded crown, which is rigid because of the thick branching at approximately right angles, and with a firm trunk of 15–40 cm (5.9–15.7 in) in diameter that is covered by 3–5 cm (1.2–2.0 in) thick greyish, reddish or blackish bark with a netting of fissures. The flowering branches are rigid, 1–1½ cm (0.4–0.6 in) thick and covered with a dense layer of white or greyish crinkly hairs or long soft silky hairs. The leaves lack a leaf stalk and stipules, ovate to lance-shaped with the greater width often beyond midlength 6–11½ cm (2.4–4.6 in) long and 2½–5 cm (1–2 in) wide, with a blunt or pointy tip, shallow or deeply incised with three to ten teeth. Dependent on the subspecies, the surface og=f the leaves is either hairless or has a dense covering of soft, greyish, convoluted hairs, occasionally with a fringe of fine hairs.[2]

The flower heads sit atop a stalk of about 1½ cm (0.6 in) long, are globe- to egg-shaped, and 7–9 cm (2.8–3.5 in) in diameter. They can be found individually or mostly with two or three together near the tip of the branch, regularly partly enclosed by leaves. The common base of the flowers of the same head is narrowly cone-shaped with a pointy tip, 2½–3 cm (1–1.2 in) long and 1–1½ cm (0.4–0.6 in) in diameter. The bracts that subtend the flower head are oval in shape with a point tip, 1¼–1½ cm (0.5–0.6 in) long and approximately 1 cm (0.39 in) wide, tightly overlapping, with a rubbery consistency and softly hairy. The bracts supporting the individual flowers enclose them at their base, have a suddenly pointed tip, and are about 2 cm (0.79 in) long, and about 1 cm (0.39 in) wide, rubbery in consistency, woolly at the base and less so near the top. The perianth is 3½–5 cm (1.4–2.0 in) long and yellow in colour. The lower 1 cm (0.4 in) is fused, cylindric, and hairless. The free parts of the four perianth claws curl back when the flower opens, those to the sides and facing the rim of the flower head densely set with long hairs. The one facing the center of the head minutely powdery or very shortly softly hairy. The perianth limbs are lance-shaped with a pointy tip, 6–8 mm (0.24–0.31 in) long, and have long hairs pressed to the surface, except for the one facing the center that is minutely powdery. The style is stout, 1–1½ mm (0.04–0.06 in) thick and 4½–5½ cm (1.8-2.2 in) long, at first bent towards the center of the flower head but getting more straight with age. It is topped by a slight thickening that is called the pollen presenter, which has a broad conical shape with a pointy tip, is 4–5 mm (0.16–0.20 in) long and about 2 mm (0.079 in) wide. Subtending the ovary are four lance-shaped scales with a pointy tip of about 2 mm (0.079 in) long.[2]

The subtribe Proteinae, to which the genus Leucospermum has been assigned, consistently has a basic chromosome number of twelve (2n=24).[3]

Differences between the subspecies

The grey tree pincushion or vaalkreupelhout in Afrikaans (subsp. conocarpodendron) has felty hairy leaves due to a dense cover of fine crisped hairs, while the green tree pincushion or groenkreupelhout (subsp. viridum) has green hairless adult leaves, sometimes with a fringe of hairs around the edge. At one location, on the east side of Little Lion's Head near Mount Rhodes, a hybrid swarm between both subspecies is found, where individual plants may have hairiness anywhere between that of both parents. Elsewhere, the populations are uniform and can easily be assigned to either of the subspecies.[2][4]

L. conocarpodendron differs from its nearest relatives by its tree-like habit, the narrowly cone-shaped common base of the flower heads, the oval involucral bracts with a pointy tip, and the broad cone-shaped pollen presenter.[2]

Taxonomy

The earliest known description of the species we now know as Leucospermum conocarpodendron was by Paul Hermann in Paradisus Batavus, a book describing the plants of the Hortus Botanicus Leiden (botanical garden of the Leyden university), that was published in 1689, three years after his death. He called it Salix conophora Africana (African cone-bearing willow), based on his observation of Leucospermum conocarpodendron on the lower slopes of the Table Mountain. In the following six decades, several other descriptions were published, such as by Leonard Plukenet, James Petiver, John Ray and Herman Boerhaave. Names published before 1753, the year that was chosen as a starting point for the binominal nomenclature proposed by Carl Linnaeus, are not valid however.

The tree pincushion was first validly described in the first edition of Species Plantarum as Leucadendron conocarpodendron by Linnaeus in 1753. Johann Jacob Reichard in 1779 reassigned the species to Protea, creating the new combination P. conocarpodendron. In 1781, Carl Peter Thunberg simplified the species name and created P. conocarpa, but because he used the same type as Linnaeus, he should have used the unchanged name. Richard Anthony Salisbury created two superfluous names, Protea tortuosa in 1796 and Leucadendrum crassicaule in 1809. In his book On the natural order of plants called Proteaceae that Robert Brown published in 1810, the species was reassigned to the new genus Leucospermum, but he combined it with Brown's invalid simplified species name to Leucospermum conocarpum. In 1874, Heinrich Wilhelm Buek made the correct combination Leucospermum conocarpodendron. Another form was described by Michael Gandoger in 1901, and he called it Leucospermum macowanii. In 1970, John Patrick Rourke proposed to distinguish between the typical subspecies (L. conocarpodendron subsp. conocarpodendron) and L. conocarpodendron subsp. viridum.[2]

L. conocarpodendron is the type species of the section conocarpodendron.[5] The species and subspecies name conocarpodendron means "tree bearing cone-shaped fruits". The subspecies name viridum means "green" and is a reference to the leaves' colour. It was called kreupelhout in Dutch (cripple wood) already before 1680, a reference to the twisted branches that together give the tree a "crippled" appearance.[4]

Distribution, habitat and ecology

L. conocarpodendron subsp. conocarpodendron is an endemic of the Cape Peninsula where it is limited to the eastern slopes of Devils Peak, the northern and western slopes of Table Mountain and the Black Table, to Llandudno. It grows mainly on heavy clay derived from the weathering of Cape Granite but also weathered Table Mountain Sandstone. It prefers north and west exposures that are well drained.[2]

L. conocarpodendron subsp. viridum has a much wider distribution that borders on that of the typical subspecies. It occupies the remainder of the Cape Peninsula from Kirstenbosch to the Cape of Good Hope. In addition, it occurs from the upper Berg River Valley, via Pringle Bay and Hermanus to Stanford. Isolated populations can also be found at Helderberg, Simonsberg, and Kogelberg near Durbanville. It occurs on such different soil types as Malmesbury gravel, sand from weathered Table Mountain Sandstone, dune sands, permanently soggy peat, and sometimes on the heavy clay that remains if Cape Granite is decomposed. It mostly grows between sea level and 150 m (490 ft), sometimes 300 m altitude. At some locations this pincushion is dominant and develops dense stands.[2]

Both subspecies have some resistance for the wildfires that occur in the fynbos every one or two decades, because the trunk is covered by a thick bark. After the fire has burnt away the soft parts, regrowth takes place from the tip of the higher branches. Repeated mild burning results in an umbrella shaped growth habit.[2]

Seed dispersal and survival greatly depends on the symbiosis of many Proteaceae with native ant species, in particular Anoplolepis steingroeveri and Pheidole capensis, that carry the fruits to their underground nests, where the elaiosome is eaten, leaving a slick and hard seed underground, safe from consumption by rodents and birds and overhead fires. The seeds would germinate after a fire, due to the larger temperature variations after the overhead vegetation has vanished and chemicals from the charcoal seep with the winter rains and soak the seeds. Seed dispersal is only limited. In an experiment, seeds on average were moved about 2 m (6½ ft) and at most about 10 m. The absence or presence of the elaiosome did not effect the germination rate, but a field trial showed that seeds without elaiosome almost never survive a fire, whereas those with elaiosome all germinated, implying that the burial of the seed by the ants is essential.[6]

Conservation

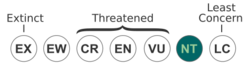

Leucospermum conocarpodendron subsp. conocarpodendron is well protected in the Table Mountain National Park, where it is locally abundant. The subspecies is nonetheless regarded a vulnerable species as a significant part of its range was lost due to urbanization and land conversion to gum plantations and invasive plant species. Further housing developments of the Cape Town agglomerations could threaten remaining habitat. Alien ant species have driven back native ants. The alien ants eat the elaiosome on the spot, so that the seed is not protected against consumption or fire. Due to the proximity of housing areas, wildfires in its range are suppressed and so allow the fynbos to develop into a thicket less suitable for the grey tree pincushion, causing the fires when they eventually occur to be hotter because of more biomass, which results in more plants dying. Finally, subsp. viridum is planted in gardens within the range of subsp. conocarpodendron, which will lead to hybridization between the subspies. This occurs even when the plants are quite far apart as both subspecies are bird pollinated. This could eventually lead to the extinction of subsp. conocarpodendron.[7][6]

References

- ↑ Rebelo, A.G.; Mtshali, H.; von Staden, L. (2020). "Leucospermum conocarpodendron". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T113171961A185570693. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T113171961A185570693.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/113171961/185570693. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Rourke, John Patrick (1970). = 1 Taxonomic Studies on Leucospermum R.Br.. pp. 49–57. https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/item/26077/thesis_sci_Rourke_1967.pdf?sequence = 1.

- ↑ Johnson, L.A.S.; Briggs, Barbara G. (1975). "On the Proteaceae—the evolution and classification of a southern family". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 70 (2): 106. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1975.tb01644.x.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Leucospermum conocarpodendron subsp. conocarpodendron and subsp. viridum". http://pza.sanbi.org/leucospermum-conocarpodendron-subsp-viridum.

- ↑ "Identifying Pincushions". https://www.proteaatlas.org.za/pincushid.htm.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Slingsby, P.; Bond, W.J. (1984). "The influence of ants on the dispersal distance and seedling recruitment of Leucospermum conocarpodendron (L.) Buek (Proteaceae)". South African Journal of Botany 51 (1): 30–34. doi:10.1016/S0254-6299(16)31698-2. https://ac.els-cdn.com/S0254629916316982/1-s2.0-S0254629916316982-main.pdf?_tid=60a6b53a-42ee-4cba-826e-0053a206a00e&acdnat=1529320918_4b3b13bafd6844862498f3dd82d42dc1.

- ↑ "Leucospermum conocarpodendron (L.) H.Buek subsp. conocarpodendron". http://pza.sanbi.org/leucospermum-conocarpodendron-subsp-conocarpodendron.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leucospermum conocarpodendron. |

Wikidata ☰ Q3642255 entry

|