Biology:Markham's storm petrel

| Markham's storm petrel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bird off Peru | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Hydrobatidae |

| Genus: | Hydrobates |

| Species: | H. markhami

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hydrobates markhami (Salvin, 1883)

| |

| |

| Distribution: blue = non-breeding | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

|

List

| |

Markham's storm petrel (Hydrobates markhami) is a seabird native to the Pacific Ocean around Peru, Chile, and Ecuador. The bird is named in honor of British explorer Albert Hastings Markham, who collected the specimen that, in 1883, lead to the scientific description of the species. It is a large and slender storm petrel, with a wingspan between 49 and 54 cm (19 and 21 in). Its plumage is black to sooty brown with a grayish bar that runs diagonally across the upper side of the wings. A member of the family Hydrobatidae, the northern storm petrels, the species is similar to the black storm-petrel (Hydrobates melania), from which it can be difficult to distinguish.

A colonial breeder, the species nests in natural cavities in salt crusts in northern Chile and Peru, with ninety-five percent of the known colonies found in the Atacama Desert. The first colony was only reported in 1993, and it is expected that more colonies are yet to be discovered. Pairs produce one egg per season, which is laid on bare ground without any nest material. Parents will attend their brood only at night, returning to the sea before dawn. The timing of the breeding season significantly varies both within and in-between colonies, for unknown reasons. The diet of Markham's storm petrel consists of fish, cephalopods such as octopuses, and crustaceans, with about ten percent of stomach contents traceable to scavenging.

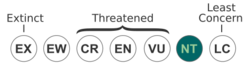

The species is listed as Near Threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Despite their relatively large population, which was estimated at between 150,000 and 180,000 individuals in 2019, the species is in decline. Primary threats are habitat destruction due to mining of the salt crusts the birds rely on for breeding, and light pollution by mines and cities near the colonies. Light pollution can attract or disorient fledglings that make their first flight to the sea, and has been estimated to be responsible for the death of around 20,000 fledglings each year, which might amount to one third of all fledglings.

Taxonomy

The ornithologist Osbert Salvin first described Markham's storm petrel as Cymochorea markhami in 1883.[2][3] The species is named after Albert Hastings Markham, a British explorer and naval officer who collected the type specimen off Peru.[4] The bird was thought by the ornithologist James L. Peters in 1931 as conspecific, or biologically identical, with Tristram's storm petrel (Oceanodroma tristrami), though the two species were later distinguished by the size of their tarsus (the "lower leg" of a bird).[2][5] Markham's storm petrel was subsequently for many years considered a member of the genus Oceanodroma.[4] Similarly, the ornithologist Reginald Wagstaffe considered Tristram's storm petrel a subspecies of Markham's storm petrel in 1972, though later research recognized them as different species.[6]

In molecular phylogenetic studies published in 2004 and 2017 the genus Oceanodroma was found to be paraphyletic (not a natural group), as the European storm petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus) is grouped within Oceanodroma.[7][8] The genus Hydrobates was introduced by Friedrich Boie in 1822 and thus has priority over Oceanodroma, which was introduced by Ludwig Reichenbach in 1853. Therefore, to create monophyletic (natural) genera, all the species in Oceanodroma were transferred to Hydrobates, including Markham's storm petrel.[9][10] The authors of the 2004 genetic study instead suggested that the species formerly in Oceanodroma should be split into smaller genera, with Markham's storm petrel and its closest relatives in Cymochorea, but this has not been followed by other authorities.[7][4]

A genetic analysis by Wallace and colleagues in 2017 found Markham's storm petrel to be the sister species of the black storm petrel.[8] This was subsequently questioned by Alvaro Jaramillo, who argued that Wallace and colleagues mistook a specimen of the black storm petrel for Markham's storm petrel. Therefore, the relationships of Markham's storm petrel to other members of its genus remain unclear.[4] The following cladogram shows the results of Wallace and colleagues, 2017.[8]

| Hydrobates |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The northern storm petrel family, Hydrobatidae, is a group of seabirds characterized by long legs and a high adaption to marine environments, with its eighteen[11] species being predominately endemic to the northern hemisphere. Within the Hydrobatidae, Markham's storm petrel is a member of the genus Hydrobates, the only genus in the family, and is large compared to other members.[4][12] Hydrobatidae probably diverged from other petrels at an early stage; according to the ornithologist John Warham, the petrel group had "substantial radiation" by the Miocene.[13] Storm petrel fossils are rare, but have been found in Upper Miocene deposits in California.[14] The researcher Rodrigo Barros and colleagues described the bird as "one of the least known seabirds in the world" in 2019.[15] While Markham's storm petrel is considered monotypic (consisting of a single species), it has been suggested that the difference in breeding time between populations could lead to allochronic speciation.[15][4]

Description

Markham's storm petrel is a large and slender storm petrel. As in other species of its genus, the wings are slender with tapering tips and a distinct wing bend at the carpus (wrist), while the tail is deeply forked. The fresh plumage is all-black to sooty brown with a dull lead-gray gloss on its head, neck, and mantle. With wear, the plumage becomes browner overall. A distinct crescent-shaped, grayish bar runs diagonally over the upper side of the inner wing. The covert feathers above this bar are often brownish, while the primaries below it are often blackish, resulting in a characteristic three-colored pattern of the wing. The iris is brown and the bill, legs, and feet are black. The bill is shorter than in most related species, whereas the nasal tube on top of the bill is long, reaching to the mid-length of the beak.[4][16][17] Adults have a wingspan between 49 and 54 cm (19 and 21 in) and measure between 21 and 23 cm (8.3 and 9.1 in) from the tip of the bill to the tip of the tail.[16] Body weight is 53 g (1.9 oz) on average.[16][4] Sexes are alike without morphological differences.[4][2]

Similar birds within its range include the black storm petrel (Hydrobates melania) and the dark variety of Leach's storm petrel (Hydrobates leucorhous). It is especially difficult to distinguish from the similar-sized black storm petrel, from which it differs in having a tarsus that is much shorter than the foot, and in that the gray bar on the upper side of the wing is more distinct and reaches closer to the leading edge of the wing. Markham's storm petrel also differs in its shorter neck and more angular head, and in the more pronounced forking of the tail. From Leach's storm petrel, it differs in its more pronounced tail forking and its longer wings and larger size. Differences in flight patterns also aid in separating these species. Markham's storm petrel typically flies leisurely and often glides with intermittent shallow wingbeats, whereas the black storm petrel glides less often and tends to use deep wingbeats. Markham's storm petrel also typically flies greater than 1 m (3.3 ft) over the ocean surface, in contrast to the black storm-petrel, which usually flies at less than one meter. Leach's storm petrel generally uses deeper wingbeats and its flight is more bouncing.[4][18][16][19]

The calls of Markham's storm petrel have been described as series of "purrs", "wheezes", and "chatters".[4] Adults in nests were found to vocalize when a recording of Markham's storm petrel vocalizations was played at the entrance.[15]

Distribution and habitat

Markham's storm petrel inhabits waters of the Humboldt Current in the Pacific Ocean off Ecuador, Peru, and northern Chile.[4][20] As these birds spend most of their lives at sea, they are considered to be endemic to the Humboldt Current.[18][21] The birds may venture as far north as southern Mexico (18°N); as far south as central Chile (30°S); and as far west as 118°W. Sightings have been reported from even farther north, off Baja California, but these might mistake Markham's storm petrel for the black storm petrel.[22][18] A survey published in 2007 found that during austral autumn (the non-breeding season), the largest concentration of birds is just off the cost of Peru between Guayaquil and Lima. During spring, this concentration splits into two, with one concentration just off southern Peru and northern Chile, and a second concentration ca. 1,700 km (1,100 mi) to the west. Adults were more common within 200 km (120 mi) of the coast, while subadults were more common at distances greater than 500 km (310 mi) from the coast. The birds were more common in the relatively shallow waters above the continental crust (the continental shelf) and less common in the deeper waters above the oceanic crust, and more common in areas where the surface water is cooler and saltier.[18] As a highly pelagic species, the birds are only rarely seen from shore.[17][16]

Despite its range, Markham's storm petrel only nests in Peru and Chile, in natural cavities in saltpeter crusts in the Atacama desert.[1] The known colonies range in area from 33 to 6,100 ha (82 to 15,073 acres), with a density between 0.5 to 248 nests per hectare. They are typically located within 25 km to the sea, at an elevation of up to 1,080 m (3,540 ft).[4] The nesting habitats are typically flat areas devoid of vegetation, but in 2021, a colony (Punta Patache) was discovered close to a lomas (fog oasis), being the first known colony associated with abundant vegetation. The location of a colony likely depends on favorable wind corridors where the birds can take advantage of sea-land winds when returning to the nest after nightfall and land-sea winds when returning to the sea before dawn.[23]

File:Chick H. markhami.webm Because the birds only return to their nests after nightfall and fly off again to sea before dawn, the detection of the breeding colonies is difficult, and their location had long been unknown.[23][4] The first colony, on the Paracas Peninsula of Peru, was only reported in 1993 and is estimated at 2,300 pairs.[23] Five additional colonies, all in northern Chile, were discovered between 2013 and 2021.[4][23] The first such colony was found in 1992 ca. 5 km (3.1 mi) inland on the Paracas Peninsula in Peru and had 1,144 nests, equal to a population of approximately 2,300 nesting pairs.[24][25] Two separate discoveries occurred in Chile in 2013: one of nesting sites south of the Acha valley in Arica Province and one of a recording of a bird singing. After further exploration in November 2013 based on the recording,[20][26] populations of 34,684 nests in Arica, 20,000 nests in Salar Grande, and 624 nests in Pampa de la Perdiz were found in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile, as reported in a 2019 study. This translated to about ninety-five percent of the known breeding population at the time. The authors of the study noted that there are two additional areas in Chile that could hold colonies based on sightings of grounded fledglings; these would then be the southernmost colonies.[15]

A 2023 study found that there were three well-supported genetic clades of Markham's storm petrel, reflecting the Paracas, Arica, and Salar Grande colonies. Their distribution was positively associated with features such as mean temperature of the wettest quarter and of the driest quarter, and solar radiation.[27]

Behavior and ecology

Like other storm petrels, Markham's storm petrel is probably monogamous. The reproductive cycle, from arrival at colonies to departure of fledglings, lasts about five months. However, some pairs will begin breeding much earlier than others – for example, in three colonies (the Paracas, Arica, and Salar de Quiña colonies), some females lay their eggs in April, while others lay their eggs as late as August. This could lead to a ten-month reproductive season of the overall colony, contrasting with most other colony-forming birds in which breeding is much more synchronized. There are also large discrepancies between colonies: In three other colonies (the Caleta Buena, Salar Grande, and Salar de Navidad colonies), egg laying occurs much later, between November and probably February. The causes of these discrepancies are unknown.[15][4]

The entries to the nest cavities measure 9.33 cm (3.67 in) in diameter on average, but range between 5.5 and 18 cm (2.2 and 7.1 in). The depth of the nest cavities was typically greater than 40 cm (16 in).[20] Storm petrel nests produce a characteristic strong smell that helps researchers to confirm that nest cavities are in use.[21][23] Pairs produce one egg per season, which is laid on bare ground inside the cavity without any lining.[24][4] The eggs are pure white without gloss,[2] and measure 32.2 by 24.2 mm (1.27 by 0.95 in) on average.[24] The egg is incubated by both parents in shifts of up to three days, during with the other partner is feeding at sea. The average incubation period was 47 days in Paracas.[4] After the chick hatches, parents return to it with food every two to three days. At the Punta Patache colony, Markham's storm petrel tends to return to their nests after nightfall between 23:00 and 01:00 and leave between 04:00 and 06:00.[23] Pairs of a colony do not cooperate in breeding.[4]

After hatching, in Chile, the fledglings move towards the sea after a chick phase.[28] Fledglings are either attracted to or disoriented by artificial lights, an occurrence common to burrow-nesting petrels.[20][29] Molting in adults probably takes place between December and May, whereas juveniles probably molt several months earlier.[17][16] At sea, the birds are typically encountered singly or in small flocks, sometimes with other storm petrel species.[4] It usually does not accompany ships.[16]

A 2007 study found that a sample of fifteen Markham's storm petrels had consumed the fish Diogenichthys laternatus and Vinciguerria lucetia, among other foods. Markham's storm petrel was found to have a lower dietary diversity than other small petrels, though dietary diversity was generally high among small petrels compared to other birds analyzed.[30] A 2002 study found its main diet by mass consisted of fish (namely the Peruvian anchovy, Engraulis ringens), cephalopods (namely the octopus Japetella sp.), and crustaceans (namely the pelagic squat lobster, Pleuroncodes monodon), with about ten percent of analyzed stomach contents suggestive of scavenging. Based on large variations in the types of food it consumes, and its tendency to scavenge, Markham's storm petrel appears to opportunistically forage near the surface of the ocean.[31] The proportion of birds that feed or rest, compared to flying in transit, was significantly higher in austral autumn than spring according to the 2007 study.[18]

Predators of adults probably include larger birds such as skuas and large gulls. Two species of fox, the Sechura fox and the South American gray fox, are important nest predators. In addition, chicks are known to be predated upon by birds of prey, dogs, and the ant Pheidole chilensis.[4] A 2018 study found the ectoparasitical stick-tight flea (Hectopsylla psittaci) on two birds out of ten captured in Pampa de Chaca within the Arica y Parinacota Region. Both specimens were found in the lorum (the region between the eyes and nostrils) on each bird. The turkey vulture (Cathartes aura) served as a possible source for the transition between hosts, as the two were observed nesting in the same colony.[32]

Status and conservation

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimated the population of Markham's storm petrel in 2019 as between 150,000 and 180,000 individuals, with between 100,000 and 120,000 of them being mature.[1] The global breeding population has been estimated at about 58,000 pairs.[33] A 2004 estimate placed the population at likely in excess of 30,000 individuals,[34] a 2007 estimate placed it at between 806,500 in austral spring and 1,100,000 in austral autumn,[18] and a 2012 estimate placed it at 50,000 overall individuals.[35] The IUCN estimates that the population of Markham's storm petrel is in decline, although the rate of decline is unknown as it is unclear how many juveniles die of natural causes.[1]

Despite its large population, in 2019, the IUCN listed the conservation status of Markham's storm petrel as Near Threatened due to habitat loss on its nesting grounds.[1] Since at least 2012, the bird has been classified as endangered in Chile,[20] and, in 2018, the Chilean Ministry of the Environment (MMA) classified the bird as in danger of extinction.[36][37] In Ecuador, (As of 2018), the species is classified as Near Endangered.[38]

Threats

The main threats to this species are habitat destruction by saltpeter mining as well as light pollution. Saltpeter mining directly destroyes nest holes and has been responsible for the loss of much breeding habitat.[1] Light pollution by the mines and nearby cities causes significant mortalities as the fledglings are attracted or disoriented by artificial lights on their first flight to sea. The exhausted birds collide with buildings or land close to the lights, which has been termed "fallout".[21] These fallen birds are often predated upon by turkey vultures after dawn.[15] A 2019 study estimates that at least 20,000 fledglings die each year due to artificial lights, which might represent one third of the fledglings of the entire population.[15] One mining company reported that 3,300 fledglings had been grounded due to their lights over a three-month span.[21]

Markham's storm petrel is also threatened by other impacts of human development in the Atacama desert.[21][1] Reported threats include new construction and development especially of power lines, solar energy parks, wind farms, and roads, which may destroy breeding habitat; garbage from roads and landfills near the colonies, which can attract predators or be blown by wind to get stuck in and possibly block the entrances to nest holes; and military activities within the colonies.[15][1] Bulldozer trails, dogs, and an encampment of road construction workers have been observed near nesting areas close to Arica.[20] A 2023 study found that 16 of 25 fledglings and all adult Markham's storm petrels examined in Chile had human-made debris (such as plastic, rubber, and cotton) in their digestive tracts, which raised concern due to the known health impact of debris on other seabirds.[39]

Markham's storm petrel is particularly sensitive to the effects of climate change because it relies on saltpeter deposits as breeding habitat: Since saltpeter deposits are limited in distribution, there will be relatively few alternative breeding areas should the currently occupied ones become unsuitable. A 2021 simulation showed that by 2080, climate change would lead to a moderate reduction in potential breeding habitat under benign climatic conditions, and to a large reduction under severe climatic conditions. The authors cautioned that their simulation does not take into account habitat loss due to human development, so that the actual habitat loss can be expected to be even more severe.[27]

Conservation efforts

Additional research is crucial for effective conservation efforts.[21][4] Priorities for research have been proposed and include the discovery of all breeding colonies, the mapping of the flight routes between colonies and the sea, the mapping of feeding areas at sea to possibly mitigate the impact of overfishing, and the monitoring of population sizes.[4]

Direct conservation efforts have been undertaken in Chile by the Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero (SAG) of the Ministry of Agriculture. In 2014, the SAG stated it already rescued a large number of juveniles who lost their way likely due to lighting in cities, a phenomenon that had been evident in the Tarapacá Region for at least ten years prior.[40] In 2018, the SAG reported it returned approximately 2,000 juvenile birds to their natural habitat after the birds fell on streets, the birds apparently believing they had already reached the coast.[28] Officials handed out informational brochures to citizens in 2019 which informed them about the start of the juvenile flight season. The brochures instructed citizens what to do if they found a grounded Markham's storm petrel.[lower-alpha 1][15][37] Similarly, in 2015, Peruvian officials instructed citizens how to transport a fallen Markham's storm petrel if they should find one.[41] In 2019, the Chilean MMA produced a plan, which included Markham's storm petrel, that sought to evaluate proposals such as updating a light pollution standard to mitigate the effects of artificial lights on the birds and designating a nesting site at Pampa de Chaca as a protected area.[42][36]

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 BirdLife International (2019). "Hydrobates markhami". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T22698543A156377889. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22698543A156377889.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22698543/156377889. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Murphy, Robert Cushman (1936). Oceanic Birds of South America: A Study of Species of the Related Coasts and Seas, Including the American Quadrant of Antarctica, Based upon the Brewster-Sanford Collection in the American Museum of Natural History. 2. The Macmillan Company. pp. 739–741. https://archive.org/details/oceanicbirdsofso02murp/page/738/mode/2up.

- ↑ Salvin, Osbert (1883). "List of the birds collected by Captain A. H. Markham on the west coast of America". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1883 (Part 3): 419–432 [430]. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/28680274.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 Drucker, J.; Jaramillo, A. (2020). Schulenberg, Thomas S. ed. "Markham's Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma markhami". Birds of the World (Cornell Lab of Ornithology). doi:10.2173/bow.maspet.01. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/maspet/cur/introduction.

- ↑ Peters, James L., ed (1931). Check-List of Birds of the World. 1 (1st ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 73–74. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/14478128.

- ↑ Christidis, Lee; Boles, Walter E., eds (2008). Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds. CSIRO Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 9780643065116. https://books.google.com/books?id=klm159tsD-oC.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Penhallurick, John; Wink, Michael (2004). "Analysis of the taxonomy and nomenclature of the Procellariiformes based on complete nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene". Emu - Austral Ornithology 104 (2): 125–147. doi:10.1071/MU01060. Bibcode: 2004EmuAO.104..125P.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Wallace, S.J.; Morris-Pocock, J.A.; González Solís, J.; Quillfeldt, P.; Friesen, V.L. (2017). "A phylogenetic test of sympatric speciation in the Hydrobatinae (Aves: Procellariiformes)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 107: 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.09.025. PMID 27693526.

- ↑ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds (July 2023). "Petrels, albatrosses". IOC World Bird List Version 13.2. International Ornithologists' Union. https://www.worldbirdnames.org/bow/petrels/.

- ↑ Chesser, R.T.; Burns, K.J.; Cicero, C.; Dunn, J.L.; Kratter, A.W; Lovette, I.J.; Rasmussen, P.C.; Remsen, J.V. Jr et al. (2019). "Sixtieth supplement to the American Ornithological Society's Check-list of North American Birds". The Auk 136 (3): 1–23. doi:10.1093/auk/ukz042.

- ↑ Winkler, David W.; Billerman, Shawn M.; Lovette, Irby J. (2020). "Hydrobatidae: Northern Storm-Petrels". Birds of the World (Cornell Lab of Ornithology). doi:10.2173/bow.hydrob1.01. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/hydrob1/cur/introduction.

- ↑ "Hydrobatinae". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&anchorLocation=SubordinateTaxa&credibilitySort=TWG%20standards%20met&rankName=Species&search_value=723247&print_version=SCR&source=from_print#SubordinateTaxa.

- ↑ Warham, John (1996). "Evolution and Radiation". The Behaviour, Population Biology and Physiology of the Petrels. Elsevier Ltd.. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-12-735415-6. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780127354156500119.

- ↑ Carboneras, C. (1992). "Family Hydrobatidae (Storm-petrels)". in del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J.. Handbook of the Birds of the World. 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. pp. 258–271 [258–259]. ISBN 84-87334-10-5. https://archive.org/details/handbookofbirdso0001unse/page/258/mode/1up.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 Barros, Rodrigo; Medrano, Fernando; Norambuena, Heraldo V.; Peredo, Ronny; Silva, Rodrigo; de Groote, Felipe; Fabrice, Schmitt (2019). "Breeding phenology, distribution and conservation status of Markham's Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma markhami in the Atacama Desert". Ardea 107 (1): 75, 77–79, 81. doi:10.5253/arde.v107i1.a1.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 Onley, Derek J.; Scofield, Paul (2007). Albatrosses, Petrels and Shearwaters of the World. Helm Field Guides. Christopher Helm. p. 232–233, 234. ISBN 9780713643329.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Howell, Steve N. G. (2012). Petrels, albatrosses, and storm-petrels of North America: a photographic guide. Princeton (N.J.): Princeton university press. pp. 427–430. ISBN 978-0-691-14211-1.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 Spear, Larry B.; Ainley, David G. (2007). "Storm-Petrels of the Eastern Pacific Ocean: Species Assembly and Diversity along Marine Habitat Gradients". Ornithological Monographs (American Ornithological Society) (62): 8, 13, 27, 37–40. doi:10.2307/40166847.

- ↑ Everett, W.T.; Bedolla-Guzmán, Y.R.; Ainley, D.G. (2021). Rodewald, P.G.. ed. "Black Storm-Petrel – Identification". Birds of the World (Cornell Lab of Ornithology). doi:10.2173/bow.bkspet.01.1. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/bkspet/cur/identification.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Torres-Mura, Juan C.; Lemus, Marina L. (2013). "Breeding of Markham's Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma markhami, Aves: Hydrobatidae) in the Desert of Northern Chile". Revista Chilena de Historia Natural (Sociedad de Biología de Chile) 86 (4): 497–499. doi:10.4067/S0716-078X2013000400013. http://rchn.biologiachile.cl/pdfs/2013/4/13_Torres-Mura_and_Lemus.pdf.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 Gilman, Sarah (July 20, 2018). "South America's Otherworldly Seabird". The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/07/storm-petrel-secret-desert-habitat-nests/563687/.

- ↑ Crossin, Richard S. (1974). "The Storm Petrels (Hydrobatidae)". in King, Warren B.. Pelagic Studies of Seabirds in the Central and Eastern Pacific Ocean. Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 187. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.158.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Carevic, Felipe S.; Sielfeld, Walter; Alarcón, Elena; del Campo, Alejandro (2023). "Discovery of a new colony and nest attendance patterns of two Hydrobates storm-petrels in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 135. doi:10.1676/22-00109. https://meridian.allenpress.com/wjo/article-abstract/doi/10.1676/22-00109/496677/Discovery-of-a-new-colony-and-nest-attendance.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Jahncke, Jamie (1993). "Primer informe del área de anidación de la golondrina de tempestad negra Oceanodroma markhami (Salvin, 1883)" [First Report of the Nesting Area of the Golondrina de Tempestad Negra Oceanodroma markhami (Salvin, 1883)]. In Castillo de Mar uenda E (ed.). Memorias X Congreso Nacional de Biología (in Spanish). pp. 339–343.

- ↑ Jahncke, Jamie (1994). "Biología y conservación de la golondrina de tempestad negra Oceanodroma markhami (Salvin 1883) en la península de Paracas, Perú" (in es). Informe Técnico (APECO).

- ↑ Schmitt, F.; Rodrigo, B.; Norambuena, H. (2015). "Markham's storm petrel breeding colonies discovered in Chile". Neotropical Birding 17: 5–10. http://www.neotropicalbirdclub.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/NB17-F1-Schmitt.pdf.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Norambuena, Heraldo V.; Rivera, Reinaldo; Barros, Rodrigo; Silva, Rodrigo; Peredo, Ronny; Hernández, Cristián E. (2021). "Living on the edge: genetic structure and geographic distribution in the threatened Markham's Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates markhami)". PeerJ 9: e12669. doi:10.7717/peerj.12669. PMID 35036151.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Yáñez, Cecilia (April 21, 2019). "La triste historia de la golondrina de mar que se está perdiendo en la ciudad" (in es). La Tercera. https://www.latercera.com/que-pasa/noticia/la-triste-historia-de-la-golondrina-de-mar-que-se-esta-perdiendo-en-la-ciudad/623058/.

- ↑ Rodríguez, Airam; Holmes, Nick D.; Ryan, Peter G.; Wilson, Kerry-Jayne; Faulquier, Lucie et al. (February 2017). "Seabird Mortality Induced by Land-based Artificial Lights". Conservation Biology (Society for Conservation Biology) 31 (5): 989. doi:10.1111/cobi.12900. PMID 28151557. Bibcode: 2017ConBi..31..986R.

- ↑ Spear, Larry; Ainley, David; Walker, William (2007). "Foraging Dynamics of Seabirds in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean". Studies in Avian Biology (Cooper Ornithological Society) 35: 1, 43, 73. https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/sab/sab_035.pdf.

- ↑ García-Godos, Ignacio; Goya, Elisa; Jahncke, Jamie (2002). "The Diet of Markham's Storm Petrel Oceanodroma markhami on the Central Coast of Peru". Marine Ornithology 30 (2): 77, 79, 81–82. http://www.marineornithology.org/PDF/30_2/4_garcia.pdf.

- ↑ Cerpa, Patrich; Medrano, Fernando; Peredo, Ronny (2018). "Jumps from Desert to the Sea: Presence of the Stick–tight Flea Hectopsylla psittaci in Markham's Storm–Petrel (Oceanodroma markhami) in the North of Chile" (in es). Revista Chilena de Ornitología (Unión de Ornitólogos de Chile) 24 (1): 40–42. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326093203.

- ↑ Medrano, Fernando; Silva, Rodrigo; Barros, Rodrigo; Terán, Daniel; Peredo, Ronny et al. (2019). "Nuevos antecedentes sobre la historia natural y conservación de la golondrina de mar negra (ocenodroma markhami) y la golondrina de mar de collar (ocenodroma hornbyi) en Chile" (in es). Revista Chilena de Ornitología (Unión de Ornitólogos de Chile) 25 (1): 26. https://aveschile.cl/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Medrano-et-al-21-30.pdf.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2018). "Hydrobates markhami". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22698543/132652667. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Hydrobates markhami". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22698543/37855907. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "Resolución exenta n° 1113: Da inicio al proceso de el aboración del plan de recuperación, conservación y gestión de las golondrinas del mar del norte de chile" (in es). Ministerio del Medio Ambiente. September 11, 2019. https://mma.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Resol_1113_sept_2019_incio_abreviado_RECOGE_golondrinas_de_mar.pdf.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "SAG inició campaña de difusión para rescate de golondrinas de mar negra" (in es). El Longino. March 19, 2019. https://www.diariolongino.cl/sag-inicio-campana-de-difusion-para-rescate-de-golondrinas-de-mar-negra/.

- ↑ Jiménez-Uzcátegu, G.; Freile, G. F.; Santander, T.; Carrasco, L.; Cisneros-Heredia, D. F.; Guevara, E. A.; Tinoco, B. A. (2018). "Listas Rojas de Especies Amenazadas en el Ecuador" (in es). Ministerio del Ambiente. p. 2. https://avesconservacion.org/web/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/evaluaci%C3%B3n_aves-ecuador_gal%C3%A1pagos_2018-2.pdf.

- ↑ Medrano Martínez, Fernando; Vargas, Macarena; Terán, Daniel; Flores, Marlene; Álvarez, Giannira; Peredo, Ronny (2023). "Ingestion of man-made debris by Markham's storm-petrel". Marine Ornithology 51: 201–203. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374615401.

- ↑ "SAG inicia rescate de golondrinas de mar negra" (in es). Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero. April 14, 2014. https://www.sag.gob.cl/noticias/sag-inicia-rescate-de-golondrinas-de-mar-negra.

- ↑ "Tacna: reportan presencia inusual de golondrinas oceánicas" (in es). El Comercio. November 21, 2015. https://elcomercio.pe/peru/tacna/tacna-reportan-presencia-inusual-golondrinas-oceanicas-244865-noticia/.

- ↑ Levi, Paula Diaz (January 22, 2020). "Continúa el ocaso de las golondrinas de mar: piden reducir contaminación lumínica y proteger sitios de nidificación" (in es). Ladera Sur. https://laderasur.com/articulo/continua-el-ocaso-de-las-golondrinas-de-mar-piden-reducir-contaminacion-luminica-y-proteger-sitios-de-nidificacion/.

External links

- Vocalizations of Markham's storm petrel from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's Macaulay Library

- Video of Markham's storm petrel from Macaulay Library

Wikidata ☰ Q939222 entry

|