Biology:Menstruation (mammal)

Menstruation is the shedding of the uterine lining (endometrium). It occurs on a regular basis in uninseminated[1] sexually reproductive-age females of certain mammal species.

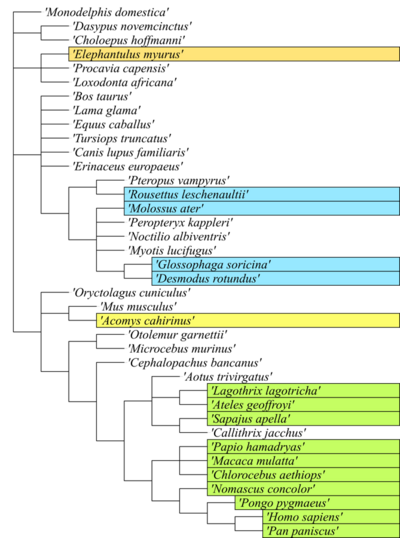

Although there is some disagreement in definitions between sources, menstruation is generally considered to be limited to primates. It is common in simians (Old World monkeys, New World monkeys, and apes), but completely lacking in strepsirrhine primates and possibly weakly present in tarsiers. Beyond primates, it is known only in bats, the elephant shrew, and the spiny mouse species Acomys cahirinus.[2][3][4][5][6] Overt menstruation (where there is bleeding from the uterus through the vagina) is found primarily in humans and close relatives such as chimpanzees.[7]

Females of other species of placental mammal undergo estrous cycles, in which the endometrium is completely reabsorbed by the animal (covert menstruation) at the end of its reproductive cycle.[8] Many zoologists regard this as different from a "true" menstrual cycle. Female domestic animals used for breeding—for example dogs, pigs, cattle, or horses—are monitored for physical signs of an estrous cycle period, which indicates that the animal is ready for insemination.

Estrus and menstruation

Females of most mammal species advertise fertility to males with visual behavioral cues, pheromones, or both.[9] This period of advertised fertility is known as oestrus, "estrus" or heat.[9] In species that experience estrus, females are generally only receptive to copulation while they are in heat[9] (dolphins are an exception).[10] In the estrous cycles of most placental mammals, if no fertilization takes place, the uterus reabsorbs the endometrium. This breakdown of the endometrium without vaginal discharge is sometimes called covert menstruation.[11] Overt menstruation (where there is blood flow from the vagina) occurs primarily in humans and close evolutionary relatives such as chimpanzees.[7] Some species, such as domestic dogs, experience small amounts of vaginal bleeding while approaching heat;[12] this discharge has a different physiologic cause than menstruation.[13]

Concealed ovulation

A few mammals do not experience obvious, visible signs of fertility (concealed ovulation). In humans, while women can learn to recognize their own level of fertility (fertility awareness), whether men can detect fertility in women is debated; recent studies have given conflicting results.[14][15]

Orangutans also lack visible signs of impending ovulation.[16] Also, it has been said that the extended estrus period of the bonobo (reproductive-age females are in heat for 75% of their menstrual cycle) [17] has a similar effect to the lack of a "heat" in human females.[18]

Evolution

Most female mammals have an estrous cycle, yet only ten primate species, four bat species, the elephant shrew, and one known species of spiny mouse have a menstrual cycle.[19][20] As these groups are not closely related, it is likely that four distinct evolutionary events have caused menstruation to arise.[21]

There are varying views on evolution of overt menstruation in humans and related species, and the evolutionary advantages in losing blood associated with dismantling the uterine lining rather than absorbing it, as most mammals do.[22] The reason is likely related to differences in the ovulation process.[21]

Most female placental mammals have a uterine lining that builds up when the animal begins ovulation, and later further increases in thickness and blood flow after a fertilized egg has successfully implanted. This final process of thickening is known as decidualization, and is usually triggered by hormones released by the embryo. In humans, decidualization happens spontaneously at the beginning of each menstrual cycle, triggered by hormonal signals from the ovaries. For this reason, the human uterine lining becomes fully thickened during each cycle as a defense to trophoblast penetration of the endometrial wall,[23] regardless of whether an egg becomes fertilized or successfully implants in the uterus. This produces more unneeded material per cycle than in non-menstruating mammals, which may explain why the extra material is not simply reabsorbed as done by those species. In essence, menstruating animals treat every estrous cycle as a possible pregnancy by thickening the protective layer around the endometrial wall, while non-menstruating placental mammals do not begin the pregnancy process until a fertilized egg has implanted in the uterine wall.

For this reason, it is speculated that menstruation is a side effect of spontaneous decidualization, which evolved in some placental mammals due to its advantages over non-spontaneous decidualization. Spontaneous decidualization allows for more maternal control in the maternal-fetal conflict by increasing selectivity over the implanted embryo.[21] This may be necessary in humans and other primates, due to the abnormally large number of genetic disorders in these species. [24] Since most aneuploidy events result in stillbirth or miscarriage, there is an evolutionary advantage to ending the pregnancy early, rather than nurturing a fetus that will later miscarry. There is evidence to show that some abnormalities in the developing embryo can be detected by endometrial stromal cells in the uterus, but only upon differentiation into decidual cells.[24]This triggers epigenetic changes that prevent formation of the placenta, which prevents the embryo from implanting and leaves it to be removed in the next menstruation.[better source needed][25] This failsafe mode is not possible in species where decidualization is controlled by hormonal triggers from the embryo. This is sometimes referred to as the choosy uterus theory, and it is theorized that this positive outweighs the negative impacts of menstruation in species with high aneuploidy rates and hence a high number of 'doomed' embryos.

Animal estrous cycles

The female will ovulate spontaneously and be receptive to the male to be bred (express estrus) at regular biologically defined intervals. The female is receptive to males only while experiencing estrus.

For breeding livestock, there are a number of advantages to be gained by finding methods to induce ovulation on a planned schedule, and thus synchronize the estrus cycle between many female animals. If animals can be bred on the same schedule, it increases convenience for the livestock owner, since the young animals will be at the same stage of development. Also, if artificial insemination (AI) is used for breeding, the AI technician's time can be used more efficiently, by breeding several females at the same time. In order to induce estrus, a variety of techniques have been tried in recent years, involving both more natural, and more hormonal based methods.[28] Different ways of injecting or feeding hormones to livestock are costly, and have variable success rates.[29]

Average length (days) of estrus and estrous cycles:[29]

| Species | Estrus | Cycle |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse, rat | 0.5 | 4 |

| Hamster | 1 | 4 |

| Rabbit | 2 | 4 |

| Guinea pig | 0.5 | 16 |

| Sheep | 2 | 17 |

| Goat | 3 | 20 |

| Cattle | 0.5 | 21 |

| Pig | 2 | 21 |

| Horse | 5 | 21 |

| Elephant | 4 | 22 |

| Red kangaroo | 3 | 35 |

| Lion | 9 | 55 |

| Dog | 7 | 60 |

See also

- Endometrium

- Estrous cycle

- Breeding pair

- Reproduction

- Animal husbandry

References

- ↑ Gras, Lyn, et al. "The incidence of chromosomal aneuploidy in stimulated and unstimulated (natural) uninseminated human oocytes." Human Reproduction 7.10 (1992): 1396-1401.

- ↑ "A missing piece: the spiny mouse and the puzzle of menstruating species". Journal of Molecular Endocrinology 61 (1): R25–R41. July 2018. doi:10.1530/JME-17-0278. PMID 29789322. https://jme.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/jme/61/1/JME-17-0278.xml.

- ↑ Profet M (September 1993). "Menstruation as a defense against pathogens transported by sperm". The Quarterly Review of Biology 68 (3): 335–86. doi:10.1086/418170. PMID 8210311.

- ↑ "The evolution of human reproduction: a primatological perspective". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 134 (S45): 59–84. 2007. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20734. PMID 18046752.

- ↑ Coutinho, Elsimar M.; Segal, Sheldon J. (1999). Is menstruation obsolete?. Oxford University Press. http://www.uwyo.edu/wjm/repro/menstrua.htm.

- ↑ Bischof, Paul; Cohen, Marie. "Course 4:Implantation". European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. http://www.eshre.eu/binarydata.aspx?type=doc&sessionId=d3g32gezrjsijs554mxn33fb/syllabus_course4%5B1%5D.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "The evolution of endometrial cycles and menstruation". The Quarterly Review of Biology 71 (2): 181–220. June 1996. doi:10.1086/419369. PMID 8693059.

- ↑ "Characteristics of the endometrium in menstruating species: lessons learned from the animal kingdom". Biology of Reproduction 102 (6): 1160–1169. June 2020. doi:10.1093/biolre/ioaa029. PMID 32129461. PMC 7253787. https://academic.oup.com/biolreprod/article/102/6/1160/5775593.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Estrus". Britannica Online. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/193725/estrus. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ↑ Mikkelson, David P. (29 June 2007). "Buried Pleasure". Snopes.com. http://www.snopes.com/critters/wild/pleasure.asp., which references:

- Diamond, Jared M. (1997). Why is sex fun?: the evolution of human sexuality. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-465-03127-6.

- ↑ "Menstruation as a defense against pathogens transported by sperm". The Quarterly Review of Biology 68 (3): 335–86. September 1993. doi:10.1086/418170. PMID 8210311.

- ↑ Pathways to Pregnancy and Parturition. Redmon, OR: Current Conceptions, Inc.. 2012. pp. 146. ISBN 978-0-9657648-3-4.

- ↑ "Canine False Pregnancy and Female Reproduction". Mar Vista Animal Medical Center. 2 February 2008. http://marvistavet.com/html/body_canine_false_pregnancy.html.

- ↑ Studies that found women are more attractive to men when fertile:

- "Female facial attractiveness increases during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle". Proceedings. Biological Sciences 271 (Suppl 5): S270–2. August 2004. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0174. PMID 15503991.

- "Ovulatory cycle effects on tip earnings by lap dancers: economic evidence for human estrus?". Evolution and Human Behavior 28 (6): 375–381. June 2007. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.06.002. http://www.unm.edu/~gfmiller/cycle_effects_on_tips.pdf. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- ↑ Study that found male sexual behavior is not affected by female fertility:

- "Women's sexual experience during the menstrual cycle: identification of the sexual phase by noninvasive measurement of luteinizing hormone". Journal of Sex Research 41 (1): 82–93. February 2004. doi:10.1080/00224490409552216. PMID 15216427. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224490409552216.

- ↑ Knott, Cheryl (2003). "Orangutans: Reproduction and Life History". Gunung Palung Orangutan Project. Harvard University. http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~gporang/orangutans.html.

- ↑ Lanting, Frans; de Waal, F. B. M. (1997). Bonobo: the forgotten ape. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 107. ISBN 978-0-520-20535-2. http://www.serpentfd.org/a/dewall1997.html. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ↑ Stanford, Craig B. (March–April 2000). "The Brutal Ape vs. the Sexy Ape? The Make-Love-Not-War Ape". American Scientist 88 (2): 110. doi:10.1511/2000.2.110.

- ↑ "Why do women menstruate?". ScienceBlogs. 2011. http://scienceblogs.com/pharyngula/2011/12/21/why-do-women-menstruate/.

- ↑ "First evidence of a menstruating rodent: the spiny mouse (Acomys cahirinus)". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 216 (1): 40.e1–40.e11. January 2017. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.07.041. PMID 27503621.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 "The evolution of menstruation: a new model for genetic assimilation: explaining molecular origins of maternal responses to fetal invasiveness". BioEssays 34 (1): 26–35. January 2012. doi:10.1002/bies.201100099. PMID 22057551.

- ↑ "The evolution of human reproduction: A primatological perspective". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 134 (S45): 59–84. 28 November 2007. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20734. PMID 18046752.

- ↑ "Cyclic Decidualization of the Human Endometrium in Reproductive Health and Failure". Endocrine Reviews 35 (6): 851–905. 1 December 2014. doi:10.1210/er.2014-1045. PMID 25141152.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Teklenburg, Gijs; Salker, Madhuri; Molokhia, Mariam; Lavery, Stuart; Trew, Geoffrey; Aojanepong, Tepchongchit; Mardon, Helen J.; Lokugamage, Amali U. et al. (2010-04-21). Vitzthum, Virginia J.. ed. "Natural Selection of Human Embryos: Decidualizing Endometrial Stromal Cells Serve as Sensors of Embryo Quality upon Implantation" (in en). PLOS ONE 5 (4): e10258. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010258. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 20422011. Bibcode: 2010PLoSO...510258T.

- ↑ "The 'choosy uterus': New insight into why embryos do not implant" (in en-us). https://medicalxpress.com/news/2013-09-choosy-uterus-insight-embryos-implant.html.

- ↑ "A missing piece: the spiny mouse and the puzzle of menstruating species" (in en-US). Journal of Molecular Endocrinology 61 (1): R25–R41. July 2018. doi:10.1530/jme-17-0278. PMID 29789322.

- ↑ "Wild fulvous fruit bats (Rousettus leschenaulti) exhibit human-like menstrual cycle". Biology of Reproduction 77 (2): 358–64. August 2007. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.106.058958. PMID 17494915.

- ↑ Synchronized mating and lambing in spring-bred Merino sheep: the use of progestogen-impregnated intravaginal sponges and teaser rams (Met opsomming in Afrikaans) (Avec resume en francais) G. L. HUNTER, P. C. BELONJE and C. H. VAN NIEKERK, Department of Agricultural Technical Services, Stellenbosch, Agroanimalia 3,133-140 (1971)

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Estrous". University of Wyoming. http://www.uwyo.edu/wjm/repro/estrous.htm.

External links

- Rasby, Rick; Vinton, Rosemary. "Estrous Cycle Learning Module". http://beef.unl.edu/learning/estrous.shtml.

- Mottershead, Jos. "The Mare's Estrous Cycle". http://www.equine-reproduction.com/articles/estrous.htm.

- May, Jerry; Bates, Ron. "Managing the Sow and Gilt Estrous Cycle". http://www.thepigsite.com/articles/2090/managing-the-sow-and-gilt-estrous-cycle.

|