Medicine:Menstruation

Menstruation (also known as a period, among other colloquial terms) is the regular discharge of blood and mucosal tissue from the inner lining of the uterus through the vagina.[1] The menstrual cycle is characterized by the rise and fall of hormones.[1] Menstruation is triggered by falling progesterone levels, and is a sign that pregnancy has not occurred.[1] Feminine hygiene products are used in order to maintain hygiene during menses.

The first period, a point in time known as menarche, usually begins during puberty, between the ages of 11 and 13.[2] However, menstruation starting as young as eight years would still be considered normal.[3] The average age of the first period is generally later in the developing world, and earlier in the developed world.[4] The typical length of time between the first day of one period and the first day of the next is 21 to 45 days in young women; in adults, the range is between 21 and 35 days with the average often cited as 28 days.[3][4] In the largest study of menstrual app data, the mean menstrual cycle length was determined to be 29.3 days.[5] Bleeding typically lasts two to seven days. Periods stop during pregnancy and typically do not resume during the initial months of breastfeeding.[3] Lochia occurs after childbirth.[6] Menstruation, and with it the possibility of pregnancy, ceases after menopause, which usually occurs between 45 and 55 years of age.[7]

During their menstrual period, 38% of all women reported not to be able to perform all their regular daily activities[8]. Symptoms in advance of menstruation that do interfere with normal life are called premenstrual syndrome (PMS). Some 20 to 30% of women experience PMS, with 3 to 8% experiencing severe symptoms.[9] These include acne, tender breasts, bloating, feeling tired, irritability, and mood changes.[10] Other symptoms some women experience include painful periods (estimates are between 50 and 90%) and heavy bleeding during menstruation and abnormal bleeding at any time during the menstrual cycle.[3] A lack of periods, known as amenorrhea, is when periods do not occur by age 15 or have not re-occurred in ninety days.[3]

Characteristics

Length and duration

The first menstrual period occurs after the onset of pubertal growth, and is called menarche. The average age of menarche is 12 to 15 years.[2][11] However, it may occur as early as eight.[3] The average age of the first period is generally later in the developing world, and earlier in the developed world.[4][12] The average age of menarche has changed little in the United States since the 1950s.[4]

Menstruation is the most visible phase of the menstrual cycle and its beginning is used as the marker between cycles. The first day of menstrual bleeding is the date used for the last menstrual period (LMP). The typical length of time between the first day of one period and the first day of the next is 21 to 45 days in young women, and 21 to 35 days in adults.[3][4] The average menstrual cycle length is conventionally said to be 28 days.[3][4] In the largest study using data from menstrual apps, the mean menstrual cycle length was determined as 29.3 days.[5] The variability of menstrual cycle lengths is highest for women under 25 years of age and is lowest, that is, most regular, for ages 25 to 39 years.[13] The variability increases slightly for women aged 40 to 44 years.[13]

Perimenopause refers to the transitional phase leading up to menopause, marked by hormonal changes and irregular menstrual cycles, when a woman stops menstruating completely and is no longer fertile. The medical definition of menopause is one year without a period and typically occurs between 45 and 55 years in Western countries.[7][14]: 381 Menopause before age 45 is considered premature in industrialized countries.[15] Illnesses, certain surgeries, or medical treatments may cause menopause to occur earlier than it might have otherwise.[16]

Menstrual fluid

The average volume of menstrual fluid during a monthly menstrual period is 35 ml (1.2 US fl oz) with 10–80 ml (0.34–2.71 US fl oz) considered typical. Menstrual fluid is the correct term for the flow, although many people prefer to refer to it as "menstrual blood". Menstrual fluid is reddish-brown, a slightly darker color than venous blood.[14]: 381

About half of menstrual fluid is blood. This blood contains sodium, calcium, phosphate, iron, and chloride, the extent of which depends on the woman. As well as blood, the fluid consists of cervical mucus, vaginal secretions, and endometrial tissue. Vaginal fluids in menses mainly contribute water, common electrolytes, organ moieties, and at least 14 proteins, including glycoproteins.[17]

Many women and girls notice blood clots during menstruation. These appear as clumps of blood that may look like tissue. If there was a miscarriage or a stillbirth, examination under a microscope can confirm if it was endometrial tissue or pregnancy tissue (products of conception) that was shed.[18] Sometimes menstrual clots or shed endometrial tissue is incorrectly thought to indicate an early-term miscarriage of an embryo. An enzyme called plasmin – contained in the endometrium – tends to inhibit the blood from clotting.[19]

The amount of iron lost in menstrual fluid is relatively small for most women. [20] In one study, premenopausal women who exhibited symptoms of iron deficiency were given endoscopies. 86% of them actually had gastrointestinal disease and were at risk of being misdiagnosed simply because they were menstruating.[non-primary source needed][21] Heavy menstrual bleeding, occurring monthly, can result in anemia.[22]

Hormonal changes

Side effects

Menstrual health overview

Moods and premenstrual syndrome (PMS)

Cramps

In most women, various physical changes are brought about by fluctuations in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle. This includes muscle contractions of the uterus (menstrual cramping) that can precede or accompany menstruation. Many women experience painful cramps, also known as dysmenorrhea, during menstruation.[23] Among adult women, 2%–28% have pain severe enough to affect daily activity.[23] Severe symptoms that disrupt daily activities and functioning may be diagnosed as premenstrual dysphoric disorder.[24] These symptoms can be severe enough to affect a person's performance at work, school, and in everyday activities in a small percentage of women.[9]

When severe pelvic pain and bleeding suddenly occur or worsen during a cycle, this could be due to ectopic pregnancy and spontaneous abortion. This is checked by using a pregnancy test, ideally as soon as unusual pain begins, because ectopic pregnancies can be life‑threatening.[25]

The most common treatment for menstrual cramps are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs can be used to reduce moderate to severe pain, and all appear similar.[26] About 1 in 5 women do not respond to NSAIDs and require alternative therapy, such as simple analgesics or heat pads.[27] Other medications for pain management include aspirin or paracetamol and combined oral contraceptives. Although combined oral contraceptives may be used, there is insufficient evidence for the efficacy of intrauterine progestogens.[26]

One review found tentative evidence that acupuncture may be useful, at least in the short term.[28] Another review found insufficient evidence to determine an effect.[29]

Interactions with other conditions

Known interactions between the menstrual cycle and certain health conditions include:

- Some women with neurological conditions experience increased activity of their conditions at about the same time during each menstrual cycle. For example, drops in estrogen levels may trigger migraines, [30] especially when the woman who has migraines is also taking the birth control pill.

- Many women with epilepsy have more seizures in a pattern linked to the menstrual cycle; this is called "catamenial epilepsy".[31] Different patterns seem to exist (such as seizures coinciding with the time of menstruation, or coinciding with the time of ovulation), and the frequency with which they occur has not been firmly established.

- Research indicates that women have a significantly higher likelihood of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the pre-ovulatory stage, than post-ovulatory stage.[32]

Sexual activity

Sexual feelings and behaviors change during the menstrual cycle. Before and during ovulation, high levels of estrogen and androgens result in women having a relatively increased interest in sexual activity, and relatively lower interest directly prior to and during menstruation.[33] Unlike other mammals, women may show interest in sexual activity across all days of the menstrual cycle, regardless of fertility.[34]

There is no reliable scientific evidence that would advise against sexual intercourse during menstruation based on medical grounds.

Fertility aspects

Peak fertility (the time with the highest likelihood of pregnancy resulting from sexual intercourse) occurs during just a few days of the cycle: usually two days before and two days after the ovulation date.[35] This corresponds to the second and the beginning of the third week in a 28-day cycle. This fertile window varies from woman to woman, just as the ovulation date often varies from cycle to cycle for the same woman.[36] A variety of methods have been developed to help individual women estimate the relatively fertile and the relatively infertile days in the cycle; these systems are called fertility awareness.

Menstrual disorders

Infrequent or irregular ovulation is called oligoovulation.[37] The absence of ovulation is called anovulation. Normal menstrual flow can occur without ovulation preceding it: an anovulatory cycle. In some cycles, follicular development may start but not be completed; nevertheless, estrogens will be formed and stimulate the uterine lining. Anovulatory flow resulting from a very thick endometrium caused by prolonged, continued high estrogen levels is called estrogen breakthrough bleeding. Anovulatory bleeding triggered by a sudden drop in estrogen levels is called withdrawal bleeding.[38] Anovulatory cycles commonly occur before menopause (perimenopause) and in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.[39]

Very little flow (less than 10 ml) is called hypomenorrhea. Regular cycles with intervals of 21 days or fewer are polymenorrhea; frequent but irregular menstruation is known as metrorrhagia. Sudden heavy flows or amounts greater than 80 ml are termed menorrhagia.[40] Heavy menstruation that occurs frequently and irregularly is menometrorrhagia. The term for cycles with intervals exceeding 35 days is oligomenorrhea.[41] Amenorrhea refers to more than three[40] to six[41] months without menses (while not being pregnant) during a woman's reproductive years. The term for painful periods is dysmenorrhea.

There is a wide spectrum of differences in how women experience menstruation. There are several ways that someone's menstrual cycle can differ from the norm:

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Oligomenorrhea | Infrequent periods |

| Hypomenorrhea | Short or light periods |

| Polymenorrhea | Frequent periods (more frequently than every 21 days) |

| Hypermenorrhea | Heavy or long periods (soaking a sanitary napkin or tampon every hour, menstruating longer than 7 days) |

| Dysmenorrhea | Painful periods |

| Intermenstrual bleeding | Breakthrough bleeding (also called spotting) |

| Amenorrhea | Absent periods |

Extreme psychological stress can also result in periods stopping.[42] More severe symptoms of anxiety or depression may be signs of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) which is a depressive disorder.[43]

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is a hormonally caused bleeding abnormality. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding typically occurs in premenopausal women who do not ovulate normally (i.e. are anovulatory). All these bleeding abnormalities need medical attention; they may indicate hormone imbalances, uterine fibroids, or other problems. As pregnant women may bleed, a pregnancy test forms part of the evaluation of abnormal bleeding.

Women who had undergone female genital mutilation (particularly type III- infibulation) a practice common in parts of Africa, may experience menstrual problems, such as slow and painful menstruation, that is caused by the near-complete sealing off of the vagina.[44]

Dysmenorrhea

Menstrual hygiene management

Menstrual products (also called "feminine hygiene" products) are made to absorb or catch menstrual blood. A number of different products are available – some are disposable, some are reusable. Where women can afford it, items used to absorb or catch menses are usually commercially manufactured products. Menstruating women manage menstruation primarily by wearing menstrual products such as tampons, napkins or menstrual cups to catch the menstrual blood.

The main disposable products (commercially manufactured) include:

- Sanitary napkins (also called sanitary towels or pads) – Rectangular pieces of material worn attached to the underwear to absorb menstrual flow, often with an adhesive backing to hold the pad in place. Disposable pads may contain wood pulp or gel products, usually with a plastic lining and bleached.

- Tampons – Disposable cylinders of treated rayon/cotton blends or all-cotton fleece, usually bleached, that are inserted into the vagina to absorb menstrual flow.

The main reusable products include:

- Menstrual cups – A firm, flexible bell-shaped device worn inside the vagina to collect menstrual flow.

- Reusable cloth pads – Pads that are made of cotton (often organic), terrycloth, or flannel, and may be handsewn (from material or reused old clothes and towels) or store-bought.

- Padded panties or period-proof underwear – Reusable cloth (usually cotton) underwear with extra absorbent layers sewn in to absorb flow.

Due to poverty, some women cannot afford commercial feminine hygiene products.[45][46] Instead, they use materials found in the environment or other improvised materials.[47][48] "Period poverty" is a global issue affecting women and girls who do not have access to safe, hygienic sanitary products.[49] In addition, solid waste disposal systems in developing countries are often lacking, which means women have no proper place to dispose used products, such as pads.[50] Inappropriate disposal of used materials also creates pressures on sanitation systems as menstrual hygiene products can create blockages of toilets, pipes and sewers.[45] In the UK research has shown that for women who are allotment growers, access to sanitation for menstrual hygiene management is limited.[51]

Menstrual suppression

Due to hormonal contraception

Menstruation can be delayed by the use of progesterone or progestins. For this purpose, oral administration of progesterone or progestin during cycle day 20 has been found to effectively delay menstruation for at least 20 days, with menstruation starting after 2–3 days have passed since discontinuing the regimen.[52]

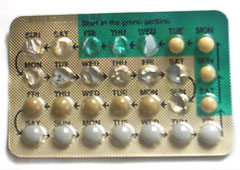

Hormonal contraception affects the frequency, duration, severity, volume, and regularity of menstruation and menstrual symptoms. The most common form of hormonal contraception is the combined birth control pill, which contains both estrogen and progestogen. Although the primary function of the pill is to prevent pregnancy, it may be used to improve some menstrual symptoms and syndromes which affect menstruation, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, adenomyosis, amenorrhea, menstrual cramps, menstrual migraines, menorrhagia (excessive menstrual bleeding), menstruation-related or fibroid-related anemia and dysmenorrhea (painful menstruation) by creating regularity in menstrual cycles and reducing overall menstrual flow.[53][54]

Using the combined birth control pill, it is also possible for a woman to delay or eliminate menstrual periods, a practice called menstrual suppression.[55] Some women do this simply for convenience in the short-term,[56] while others prefer to eliminate periods altogether when possible. This can be done either by skipping the placebo pills, or using an extended cycle combined oral contraceptive pill, which were first marketed in the U.S. in the early 2000s. This continuous administration of active pills without the placebo can lead to the achievement of amenorrhea in 80% of users within 1 year of use.[57]

Due to breastfeeding

Breastfeeding causes negative feedback to occur on pulse secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).[58] Depending on the strength of the negative feedback, breastfeeding women may experience complete suppression of follicular development, follicular development but no ovulation, or normal menstrual cycles may resume.[59] Suppression of ovulation is more likely when suckling occurs more frequently.[60] The production of prolactin in response to suckling is important to maintaining lactational amenorrhea.[61] On average, women who are fully breastfeeding whose infants suckle frequently experience a return of menstruation at fourteen and a half months postpartum. There is a wide range of response among individual breastfeeding women, however, with some experiencing return of menstruation at two months and others remaining amenorrheic for up to 42 months postpartum.[62]

Society and culture

Etymology and terminology

The word menstruation is etymologically related to moon. The terms menstruation and menses are derived from the Latin mensis 'month', which in turn relates to the ancient Greek mene 'moon' and to the roots of the English words month and moon.[63]

Some organizations have begun to use the term "menstruator" instead of "menstruating women", a term that has been in use since at least 2010.[64] Menstruator is used by activists and scholars in order to "express solidarity with women who do not menstruate, transgender men who do, and intersexual and genderqueer individuals".[64]: 950 The term can be contentious between different schools of feminist thought; however, the argument is made that since gender identities are lived, the reality is that people of different genders menstruate.[64]: 950 The term "people who menstruate" is also used.[65]

Traditions, taboos and education

Many religions have menstruation-related traditions, for example: Islam prohibits sexual contact with women during menstruation in the 2nd chapter of the Quran.[66] Some scholars argue that menstruating women are in a state in which they are unable to maintain wudhu, and are therefore prohibited from touching the Arabic version of the Qur'an.[67] In Judaism, a woman during menstruation is called Niddah and may be banned from certain actions. For example, the Jewish Torah prohibits sexual intercourse with a menstruating woman.[68] In Hinduism, menstruating women are traditionally considered ritually impure and given rules to follow.[69][70] In Zoroastrianism, if a woman's menses did not stop after nine days, it was considered the work of the daēvas.[71]

Menstruation education is frequently taught in combination with sex education at school in Western countries, although girls may prefer their mothers to be the primary source of information about menstruation and puberty.[72] Information about menstruation is often shared among friends and peers, which may promote a more positive outlook on puberty.[73] The quality of menstrual education in a society determines the accuracy of people's understanding of the process.[74] In many Western countries where menstruation is a taboo subject, girls tend to conceal the fact that they may be menstruating and struggle to ensure that they give no sign of menstruation.[74] Effective educational programs are essential to providing children and adolescents with clear and accurate information about menstruation. Schools can be an appropriate place for menstrual education to take place.[75] Programs led by peers or third-party agencies are another option.[75] Low-income girls are less likely to receive proper sex education on puberty, leading to a decreased understanding of why menstruation occurs and the associated physiological changes that take place. This has been shown to cause the development of a negative attitude towards menstruation.[76]

Seclusion during menstruation

In some cultures, women were isolated during menstruation due to menstrual taboos.[77] This is because they are seen as unclean, dangerous, or bringing bad luck to those who encounter them. These practices are common in parts of South Asia including India.[78] A 1983 report found women refraining from household chore during this period in India.[79] Chhaupadi is a social practice that occurs in the western part of Nepal for Hindu women, which prohibits a woman from participating in everyday activities during menstruation. Women are considered impure during this time and are kept out of the house and have to live in a shed. Although chhaupadi was outlawed by the Supreme Court of Nepal in 2005, the tradition is slow to change.[80][81] Women and girls in cultures which practice such seclusion are often confined to menstruation huts, which are places of isolation used by cultures with strong menstrual taboos. The practice has recently come under fire due to related fatalities. Nepal criminalized the practice in 2017 after deaths were reported after the elongated isolation periods, but "the practice of isolating menstruating women and girls continues."[82] Not all cultures villainize menstruation, the Beng people of West Africa consider menstrual blood as sacred and recognize its significance in reproduction.[83]

Beliefs around synchrony

Effects of the moon

Even though the average length of the human menstrual cycle is similar to that of the lunar cycle, in modern humans there is no relation between the two.[84] The relationship is believed to be a coincidence.[85][86] Light exposure does not appear to affect the menstrual cycle in humans.[87] A meta-analysis of studies from 1996 showed no correlation between the human menstrual cycle and the lunar cycle,[88] nor did data analyzed by period-tracking app Clue, submitted by 1.5 million women, of 7.5 million menstrual cycles; however, the lunar cycle and the average menstrual cycle were found to be basically equal in length.[89]

Cohabitation

Beginning in 1971, some research suggested that menstrual cycles of cohabiting women became synchronized (menstrual synchrony).[90] Subsequent research has called this hypothesis into question.[91] A 2013 review concluded that menstrual synchrony likely does not exist.[92]

Work

Some countries, mainly in Asia, have menstrual leave to provide women with either paid or unpaid leave of absence from their employment while they are menstruating.[93] Countries with policies include Japan, Taiwan, Indonesia, and South Korea.[94][95] The practice is controversial due to concerns that it bolsters the perception of women as weak, inefficient workers,[93] as well as concerns that it is unfair to men,[96][97] and that it furthers gender stereotypes and the medicalization of menstruation.[94]

Other mammals

Most female mammals have an estrous cycle, but not all have a menstrual cycle that results in menstruation. Menstruation in mammals occurs in some close evolutionary relatives such as chimpanzees.[98]

See also

- Niddah (Jewish laws of menstruation)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Thiyagarajan, Dhanalakshmi K.; Basit, Hajira; Jeanmonod, Rebecca (27 September 2024). "Physiology, Menstrual Cycle". StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing). PMID 29763196. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500020/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Women's Gynecologic Health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 2011. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-7637-5637-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=pj_ourS3PBMC&pg=PA94.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 "Menstruation and the menstrual cycle fact sheet". 23 December 2014. http://www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/menstruation.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 "Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign". Pediatrics 118 (5): 2245–2250. November 2006. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2481. PMID 17079600.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Real-world menstrual cycle characteristics of more than 600,000 menstrual cycles". npj Digital Medicine 2 (1). 2019-08-27. doi:10.1038/s41746-019-0152-7. PMID 31482137.

- ↑ "Pregnancy: Physical Changes After Delivery". https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/9682-pregnancy-physical-changes-after-delivery.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Menopause: Overview". 28 June 2013. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/menopause.

- ↑ "The impact of menstrual symptoms on everyday life: a survey among 42,879 women". Am J Obstet Gynecol 220 (6). 2019. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.048. PMID 30885768.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder". American Family Physician 84 (8): 918–924. October 2011. PMID 22010771.

- ↑ "Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) fact sheet". 23 December 2014. http://www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/premenstrual-syndrome.html.

- ↑ "Determinants of menarche". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 8: 115. September 2010. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-8-115. PMID 20920296.

- ↑ "Is Female Health Cyclical? Evolutionary Perspectives on Menstruation". Trends in Ecology & Evolution 33 (6): 399–414. June 2018. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2018.03.006. PMID 29778270. Bibcode: 2018TEcoE..33..399A.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "The length and variability of the human menstrual cycle". JAMA 203 (6): 377–380. February 1968. doi:10.1001/jama.1968.03140060001001. PMID 5694118.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 The new Harvard guide to women's health. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 2004. ISBN 0-674-01343-3. https://archive.org/details/newharvardguidet00carl.

- ↑ "Clinical topic — Menopause". NHS. http://www.cks.nhs.uk/menopause#-292420.

- ↑ "EMAS position statement: Predictors of premature and early natural menopause". Maturitas 123: 82–88. May 2019. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.03.008. PMID 31027683.

- ↑ The Vulva: Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology. CRC Press. 22 Mar 2013. pp. 155–158.

- ↑ "Menstrual blood problems: Clots, color and thickness". http://women.webmd.com/menstrual-blood-problems-clots-color-and-thickness.

- ↑ C. J. Dockeray, B. L. Sheppard, L. Daly, J. Bonnar (April 1987), "The fibrinolytic enzyme system in normal menstruation and excessive uterine bleeding and the effect of tranexamic acid", European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 24 (4): 309–318, doi:10.1016/0028-2243(87)90156-0, ISSN 0301-2115, PMID 2953634

- ↑ "Iron-deficiency is not something you get just for being a lady". SciAm. 27 July 2011. http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/context-and-variation/2011/07/27/iron-deficiency-anemia/.

- ↑ "A prospective, multidisciplinary evaluation of premenopausal women with iron-deficiency anemia". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 94 (1): 109–115. January 1999. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00780.x. PMID 9934740.

- ↑ "A Review of Clinical Guidelines on the Management of Iron Deficiency and Iron-Deficiency Anemia in Women with Heavy Menstrual Bleeding". Advances in Therapy 38 (1): 201–225. January 2021. doi:10.1007/s12325-020-01564-y. PMID 33247314.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea". Epidemiologic Reviews 36 (1): 104–113. 1 January 2014. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxt009. PMID 24284871.

- ↑ "Premenstrual syndrome (PMS)" (in en). 12 July 2017. https://www.womenshealth.gov/menstrual-cycle/premenstrual-syndrome.

- ↑ "Ectopic Pregnancy Clinical Presentation: History, Physical Examination". http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2041923-clinical.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Dysmenorrhoea". BMJ Clinical Evidence 2014: 390–400. October 2014. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.08.108. PMID 25338194.

- ↑ "Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug resistance in dysmenorrhea: epidemiology, causes, and treatment". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 218 (4): 390–400. April 2018. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.08.108. PMID 28888592.

- ↑ "The efficacy and safety of acupuncture in women with primary dysmenorrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Medicine 97 (23). June 2018. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011007. PMID 29879061.

- ↑ "Acupuncture for dysmenorrhoea". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016 (4). April 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007854.pub3. PMID 27087494.

- ↑ "The complex relationship between estrogen and migraines: a scoping review". Systematic Reviews 10 (1). March 2021. doi:10.1186/s13643-021-01618-4. PMID 33691790.

- ↑ "Catamenial epilepsy: definition, prevalence pathophysiology and treatment". Seizure 17 (2): 151–159. March 2008. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2007.11.014. PMID 18164632.

- ↑ "Non-contact ACL injuries in female athletes: an International Olympic Committee current concepts statement". British Journal of Sports Medicine 42 (6): 394–412. June 2008. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.048934. PMID 18539658.

- ↑ "Women's Bodies". Discovering Human Sexuality. Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc.. 2015. pp. 44. ISBN 978-1-60535-275-6.

- ↑ "Background and Overview of the Book". The Evolutionary Biology of Human Female Sexuality. New York: Oxford University Press. 2008. pp. 12. ISBN 978-0-19-534099-0.

- ↑ "My Fertile Period". DuoFertility. Cambridge Temperature Concepts Limited. http://www.duofertility.com/en/my-body/my-cycle/my-fertile-period.html.

- ↑ "How regular is regular? An analysis of menstrual cycle regularity". Contraception 70 (4): 289–292. October 2004. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2004.04.012. PMID 15451332.

- ↑ "Oligoovulation". about.com. 16 April 2008. http://pcos.about.com/od/glossary/g/oligoovulation.htm.

- ↑ Taking Charge of Your Fertility (Revised ed.). New York: HarperCollins. 2002. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-06-093764-5. https://archive.org/details/takingchargeofyo00toni.

- ↑ Anovulation at eMedicine

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Menstruation Disorders at eMedicine

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "Abnormal uterine bleeding". American Family Physician 60 (5): 1371–80; discussion 1381–2. October 1999. PMID 10524483. http://www.aafp.org/link_out?pmid=10524483.

- ↑ "Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea and its influence on women's health". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 37 (11): 1049–1056. November 2014. doi:10.1007/s40618-014-0169-3. PMID 25201001.

- ↑ "Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. 2022. NBK532307.

- ↑ "Health risks of female genital mutilation (FGM)". https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/health_consequences_fgm/en/.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Menstrual Hygiene, Management, and Waste Disposal: Practices and Challenges Faced by Girls/Women of Developing Countries". Journal of Environmental and Public Health 2018. 2018. doi:10.1155/2018/1730964. PMID 29675047.

- ↑ "Girls 'too poor' to buy sanitary protection missing school". BBC News. 14 March 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-39266056.

- ↑ Chin L (2014). Period of shame - The effects of menstrual hygiene management on rural women and girls' quality of life in Savannakhet, Laos (Thesis). Archived from the original on 7 December 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ↑ "Menstrual Hygiene Matters: a resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world". Reproductive Health Matters 21 (41): 257–259. 2013.

- ↑ "Period poverty". https://www.actionaid.org.uk/about-us/what-we-do/womens-economic-empowerment/period-poverty.

- ↑ Global Review of Sanitation System Trends and Interactions with Menstrual Management Practices: Report for the Menstrual Management and Sanitation Systems Project. (Report). Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI). https://www.susana.org/en/knowledge-hub/resources-and-publications/library/details/1556.

- ↑ Cox, Elizabeth (2023-12-12). "Leaks and pees: How women allotment gardeners manage bodily mess and the remains of early loss" (in English). The Sociological Review Magazine. doi:10.51428/tsr.tour5403. https://thesociologicalreview.org/magazine/december-2023/mess/leaks-and-pees/.

- ↑ "Progestin potency – Assessment and relevance to choice of oral contraceptives". Middle East Fertility Society Journal 16 (4): 248–253. 1 December 2011. doi:10.1016/j.mefs.2011.08.006.

- ↑ CYWH Staff (2011-10-18). "Medical Uses of the Birth Control Pill". http://www.youngwomenshealth.org/med-uses-ocp.html.

- ↑ "U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports 65 (3): 1–103. July 2016. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6503a1. PMID 27467196.

- ↑ "Delaying your period with birth control pills". Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/womens-health/WO00069.

- ↑ "How can I delay my period while on holiday?". National Health Service, United Kingdom. http://www.nhs.uk/chq/Pages/830.aspx?CategoryID=60&SubCategoryID=179.

- ↑ "Monthly Periods--Are They Necessary?". Pediatric Annals 44 (9): e231–e236. September 2015. doi:10.3928/00904481-20150910-11. PMID 26431242.

- ↑ (in en) Infant and Young Child Feeding. World Health Organization. 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK148970/. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ↑ "Lactational control of reproduction". Reproduction, Fertility, and Development 13 (7–8): 583–590. 2001. doi:10.1071/RD01056. PMID 11999309.

- ↑ The Art of Natural Family Planning (4th ed.). Cincinnati, OH: The Couple to Couple League. 1996. p. 347. ISBN 0-926412-13-2.

- ↑ "Prolactin response to suckling and maintenance of postpartum amenorrhea among intensively breastfeeding Nepali women". Endocrine Research 22 (1): 1–28. February 1996. doi:10.3109/07435809609030495. PMID 8690004.

- ↑ "Breastfeeding: Does It Really Space Babies?". The Couple to Couple League International. Internet Archive. 17 January 2008. http://www.ccli.org/nfp/ebf/spacebabies.php., which cites:

- "The relation between breastfeeding and amenorrhea: report of a survey". JOGN Nursing; Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 1 (4): 15–21. November–December 1972. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.1972.tb00558.x. PMID 4485271.

- "Breastfeeding survey results similar to 1971 study". The CCL News 13 (3): 10. November–December 1986.

- "Breastfeeding survey results similar to 1971 study". The CCL News 13 (4): 5. January–February 1987.

- ↑ The Reluctant Hypothesis: A History of Discourse Surrounding the Lunar Phase Method of Regulating Conception. Lacuna Press. 2007. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-9510974-2-7.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 "Degendering Menstruation: Making Trans Menstruators Matter" (in en). The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Singapore: Springer Singapore. 2020. pp. 945–959. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_68. ISBN 978-981-15-0613-0.

- ↑ "J.K. Rowling accused of transphobia after mocking 'people who menstruate' headline" (in en). NBC News. 7 June 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/j-k-rowling-accused-transphobia-after-mocking-people-who-menstruate-n1227071.

- ↑ "Surah Al-Baqarah - 222". https://quran.com/al-baqarah/222.

- ↑ "Chapter: 6, Menstrual Periods". ahadith.co.uk. http://ahadith.co.uk/chapter.php?cid=28.

- ↑ Leviticus 15:19-30, 18:19, 20:18

- ↑ "Restriction and renewal, pollution and power, constraint and community: The paradoxes of religious women's experiences of menstruation.". Sex Roles 68 (1): 12–31. January 2013. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0132-8.

- ↑ "Menstruation related myths in India: strategies for combating it". Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 4 (2): 184–186. 2015. doi:10.4103/2249-4863.154627. PMID 25949964.

- ↑ Wolff, Fritz. Avesta: The Sacred Books Parsen.

- ↑ "The Role of Mother in Informing Girls About Puberty: A Meta-Analysis Study". Nursing and Midwifery Studies 5 (1). March 2016. doi:10.17795/nmsjournal30360. PMID 27331056.

- ↑ "Effect of peer education in school on sexual health knowledge and attitude in girl adolescents". Journal of Education and Health Promotion 4: 78. 2015-12-30. doi:10.4103/2277-9531.171791. PMID 27462620.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 "More than just a punctuation mark: How boys and young men learn about menstruation". Journal of Family Issues 32 (2): 129–56. February 2011. doi:10.1177/0192513x10371609.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 "The impact of schools and school programs upon adolescent sexual behavior". Journal of Sex Research 39 (1): 27–33. February 2002. doi:10.1080/00224490209552116. PMID 12476253.

- ↑ "Puberty Experiences of Low-Income Girls in the United States: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Literature From 2000 to 2014". The Journal of Adolescent Health 60 (4): 363–379. April 2017. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.10.008. PMID 28041680.

- ↑ "Menstrual Taboos: Moving Beyond the Curse". The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Palgrave Macmillan. 2020. pp. 143–162. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_14. ISBN 978-981-15-0614-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565616/. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ↑ Culture and Depression: Studies in the Anthropology and Cross-Cultural Psychiatry of Affect and Disorder. University of California Press. 1985. pp. 203–204. ISBN 978-0-520-05883-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=27UwDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA182.

- ↑ The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation. University of Illinois Press. 1988. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-252-01452-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=njfQfrMr31EC&pg=PR9.

- ↑ "Nepal: Emerging from menstrual quarantine". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). August 2011. http://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?page=publisher&publisher=IRIN&type=&coi=NPL&docid=4e3f7ae82&skip=0.

- ↑ "Women hail menstruation ruling". BBC News. 15 September 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4250506.stm.

- ↑ "Menstrual Health and the Problem with Menstrual Stigma". The Federation of American Women's Clubs Overseas, Inc. (FAWCO). September 2019. https://www.fawco.org/global-issues/target-program/health/blog-health-matters/4146-sample.

- ↑ "Egyptians used papyrus—and other ways of handling periods through the years" (in en). 2023-11-29. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/periods-menstruation-women-history-ancient-egypt.

- ↑ Vertebrate Endocrinology (5 ed.). Academic Press. 2013. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-12-396465-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=F_NaW1ZcSSAC&pg=PA361.

- ↑ 1001 things everyone should know about the universe (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. 1997. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-385-48223-3.

- ↑ "Synchrony and Its Discontents". How women got their curves and other just-so stories evolutionary enigmas ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. 2009. ISBN 978-0-231-51839-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=fZM2AAAAQBAJ&pg=PT64.

- ↑ Human Reproductive Biology. Academic Press. 2013. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-12-382185-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=M4kEdSnS-pkC&pg=PA53.

- ↑ "What's the link between the moon and menstruation?". The Straight Dope. 24 September 1999. http://www.straightdope.com/classics/a990924.html.: Science and the Paranormal: Probing the Existence of the Supernatural. Scribner Book Company. 1983. ISBN 978-0-684-17820-2.

- ↑ "The myth of moon phases and menstruation". Clue. 3 December 2018. https://helloclue.com/articles/cycle-a-z/myth-moon-phases-menstruation.

- ↑ "Regulation of ovulation by human pheromones". Nature 392 (6672): 177–179. March 1998. doi:10.1038/32408. PMID 9515961. Bibcode: 1998Natur.392..177S.

- ↑ "Does menstrual synchrony really exist?". The Straight Dope. The Chicago Reader. 20 December 2002. http://www.straightdope.com/columns/021220.html.

- ↑ "Darwin's legacy: an evolutionary view of women's reproductive and sexual functioning". Journal of Sex Research 50 (3–4): 207–246. 2013. doi:10.1080/00224499.2012.763085. PMID 23480070.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 "Should Paid 'Menstrual Leave' Be a Thing?". The Atlantic. 16 May 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/05/should-women-get-paid-menstrual-leave-days/370789/.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 "Addressing Menstruation in the Workplace: The Menstrual Leave Debate". The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Palgrave Macmillan. 2020. pp. 561–575. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_43. ISBN 978-981-15-0614-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565643/.

- ↑ King S. (2021) Menstrual Leave: Good Intention, Poor Solution. In: Hassard J., Torres L.D. (eds) Aligning Perspectives in Gender Mainstreaming. Aligning Perspectives on Health, Safety and Well-Being. Springer, Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-53269-7_9

- ↑ "Should women get paid menstruation leave?". 11 October 2006. http://www.salon.com/2006/10/11/menstruation_4/.

- ↑ "Menstrual Leave: Delightful or Discriminatory?". 4 August 2013. http://lipmag.com/culture/menstrual-leave-delightful-or-discriminatory/.

- ↑ "The evolution of endometrial cycles and menstruation". The Quarterly Review of Biology 71 (2): 181–220. June 1996. doi:10.1086/419369. PMID 8693059.

Sources

- "Psychology, gender, and health: psychological aspects of the menstrual cycle". The Psychology of Women and Gender: Half the Human Experience (10th ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE Publishing. 2021. ISBN 978-1-544-39360-5.

- "The menstrual cycle: its biology in the context of silent ovulatory disturbances". Routledge International Handbook of Women's Sexual and Reproductive Health (1st ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. 2020. ISBN 978-1-138-49026-0. OCLC 1121130010.

Further reading

- Bobel, C.; Winkler, I. T.; Fahs, B.; Hasson, K. A.; Kissling, E. A.; Roberts, T. A. (2020). The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7. ISBN 978-981-15-0614-7. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7.

- Maria Kathryn Tomlinson (2025). The Menstrual Movement in the Media. Palgrave Studies in Communication for Social Change. Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-72195-3. ISBN 978-3-031-72195-3. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-72195-3.

- Habeeb, Saima (2023). "Menstruation". in Shackelford Todd K. (in en). Encyclopedia of Sexual Psychology and Behavior. Springer, Cham. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-08956-5_1521-1. ISBN 978-3-031-08956-5. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-031-08956-5_1521-1.

External links

|