Biology:Mortierella polycephala

| Mortierella polycephala | |

|---|---|

| |

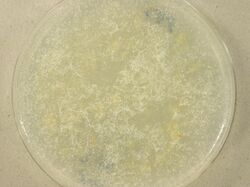

| UAMH 1152 grown on oatmeal agar at 25 C for 66 days | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | M. polycephala

|

| Binomial name | |

| Mortierella polycephala Coemans (1863)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Mortierella polycephala is a saprotrophic fungus[1] with a wide geographical distribution[2] occurring in many different habitats from soil and plants to salt marshes and slate slopes.[2] It is the type species of the genus Mortierella,[3] and was first described in 1863 by Henri Coemans.[4] A characteristic feature of the fungus is the presence of stylospores, which are aerial, spiny resting spores (chlamydospores).[5]

History and taxonomy

M. polycephala was the first species described in the genus Mortierella[6] of the phylum Zygomycota. It has been observed on feces of bats and rodents, such as mice and rats,[2] and it was first described by Coemans on the Bulletin de l'Académie Royale des Sciences de Belgique in 1863.[4] Coemans isolated it from wood rot polypore fungi in the genera Daedalea and Polyporus, however he did not study the mycelium or the chlamydospores.[7] The study of the previous characteristics was done by Van Tieghem who described the sporangia, chlamydospores and stylospores.[7] The species is characterized by the presence of many stylospores (aerial chlamydospores)[2] and sporangiospores arising from aerial hyphae.[8] Jean Dauphin, a professor at The University of Paris dedicated 28 pages to the description, study and experimentation on M. polycephala in his publication Contribution à l'Étude des Mortierellées (1908).[9] In his paper, this species was the only one in which external factors were assessed to determine their role in stimulating the production of zygospores.[9] M. indohii has been proposed as a closely related species to M. polycephala by several studies[5][3] based on the production of stylospores by both species. Based on phylogenetic analyses where the complete ITS region, and LSU and SSU genes were assessed, close relationship between the two species has been proposed.[3]

Growth and morphology

Colonies are white[1] with a spider web-like texture and sparse growth;[10] they have a garlic-like aroma[11] and can measure up to 7.5 cm in diameter after 5 days at 20 °C on malt extract agar.[2] Sporangiophores in this species measure 300–500 μm long: they are 12.5–20 μm wide at the base,[10] being reduced to 3.5–5 μm at the tip.[8] They can be single or come in clusters; primary branches are present mostly in the upper part of the sporangiophore and they may give rise to secondary and tertiary branches of 12–90 μm long.[8] Sporangia are brown,[8] round (globose), with a diameter of 37–75 μm[10] and they can contain 4–20 spores.[7] M. polycephala' sporangia can grow well between 10 °C and 25 °C, with an optimum temperature of about 17 °C.[7] Sporangiospores are hyaline,[8] they measure 5.5–13.2 μm long and have an oval to irregular shape.[10] The optimum germination temperature is 27 °C.[7] Zygospores can be up to 1 mm in diameter andare produced by both homothallic and heterothallic mechanisms;[10] they are well formed between 15 °C and 22 °C.[7] Stylospores can be aerial or submerged,[6] they are hyaline and can be found alone or in groups.[7] Their diameter is around 20 μm.[7]

Physiology

M. polycephala is able to decompose chitin, liquify gelatin, and produce ethanol, oxalic acid and acetic acid if grown on a glucose medium.[2] Minimal growth is observed at 4 °C; 17 °C is optimal for growth, and growth is not observed above 27 °C.[7] In his experiments Dauphin exposed the fungus to extremely low temperature using liquid air. He observed that at −180 °C (−292.0 °F), the spores of M. polycephala did not germinate but were not killed and germinated once returned to ambient temperature. At 4 °C, the chlamydospores and spores could germinate after 3 days and the mycelium was not abundant, yielding this as the minimum temperature at which M. polycephala could grow. At 15 °C germination was the best for M. polycephala: it took 2 days and the mycelium was abundant, but not too crowded. From 22–27 °C mycelium generation started to occur too fast and too crowded; and at 32 °C conditions started to get unhealthy for germination. Finally at 45 °C and higher temperatures, the spores died and germination was not possible.[7] Dauphin also discussed the effects of the lack of oxygen in the fungus growth and concluded it was not a determining factor affecting germination.[7]

Growth of M. polycephala' occurs best in natural or artificial light, and is reduced when colonies are grown in darkness; although no difference in size or morphology of fructifications is seen between colonies developed under differing lighting conditions.[7] M. polycephala grows more slowly under thermal radiation than under longer wavelengths (violet, ultraviolet, blue light) where germination is accelerated.[7] M. polycephala shows a tolerance to short-duration X-ray exposure. Longer periods of x-ray exposure result in slowed germination or death.[7] Dauphin used a radium tube given to him by Professor Pierre Curie to assess the tolerance of M. polycephala to ionizing radiation. He placed the fungus on a Petri dish, and situated the aperture of the radium source towards the centre of the dish. He found that at the borders of the dish, where radiation was more distant, germination was not affected: it was more abundant than normal; however, towards the centre of the dish growth became reduced.[7] He also compared fungal growth exposed to radium with growth under normal conditions using duplicate cultures of the same strain of M. polycephala. The control yielded normal growth and development, but the radium-exposed culture manifested double or triple the normal growth rate in some filaments while others developed cysts.[7]

Habitat and ecology

M. polycephala has been reported on decaying polypores, arable and desert soil, trees such as beech and spruce, flowering plants like Calluna, alfalfa roots, wheat, tomato and cabbage; and other ecosystems like salt marshes and slate slopes.[2] It is a saprotroph fungi,[1] extensively distributed in Europe: Belgium, France , The Netherlands, United Kingdom , Ukraine ,[1] Germany and Switzerland ;[2] Asia: China , Japan ,[1] India and Indonesia;[2] and America: Brazil and Mexico.[2] Its spores are transmitted via air or water movement.[1] Although several articles and books report M. polycephala as a cause of pulmonary infections for cattle[10][12][13][2] and abortion in cattle,[2] a primary source that confirms this statement has not been found and no other sources have reproduced the findings. A single report of animal infection attributed M. polycephala may represent a misidentified strain of M. wolfii.[14]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Kirk, PM (1997). "Mortierella polycephala". IMI Descriptions of Fungi and Bacteria 1307: 1–2.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 Domsch, KH; Gams, Walter; Andersen, TH (1980). Compendium of soil fungi (2nd ed.). London, UK: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0122204012. https://archive.org/details/tudesdesciencer00putsgoog.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Petkovits, T; Nagy, LG; Hoffmann, K; Wagner, L; Nyilasi, I; Griebel, T; Schnabelrauch, D; Vogel, H et al. (2011). "Data Partitions, Bayesian Analysis and Phylogeny of the Zygomycetous Fungal Family Mortierellaceae, Inferred from Nuclear Ribosomal DNA Sequences". PLOS ONE 6 (11): e27507. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027507. PMID 22102902. Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...627507P.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wagner, L.; Stielow, B.; Hoffmann, K.; Petkovits, T.; Papp, T.; Vágvölgyi, C; de Hoog, CS; Verkley, G. et al. (2013). "A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of the Mortierellales (Mortierellomycotina) based on nuclear ribosomal DNA". Persoonia 30: 77–93. doi:10.3767/003158513X666268. PMID 24027348.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Chien, CY; Kuhlman, EG; Gams, W (1974). "Zygospores in two Mortierella species with "Stylospores"". Mycologia 66 (1): 114–121. doi:10.1080/00275514.1974.12019580.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Yadav, DR; Kim, SW; Adhikari, M; Kim, HS; Kim, C; Lee, HB; Lee, YS (2015). "Three New Records of Mortierella Species Isolated from Crop Field Soil in Korea". Mycobiology 43 (3): 203–209. doi:10.5941/MYCO.2015.43.3.203. PMID 26539035.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 Dauphin, J (1908). "Contribution à l'étude de Mortiérellées". Ann Sci Nat Bor 8 (2): 1–112.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Mehrotra, BS; Baijal, U (1963). "Species of Mortierella from India-III". Mycopathol. Mycol. Appl. 20 (1–2): 49–54. doi:10.1007/bf02054875. PMID 14057952.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Blakeslee, AF (1909). "Papers on Mucors". Bot Gaz 47 (5): 418–423. doi:10.1086/329901.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 de Hoog, GS; Guarro, J; Gené, J; Figueras, MJ (2000). Atlas of Clinical Fungi. The Netherlands: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures/Universitat Rovira i Virgili. ISBN 978-9070351434.

- ↑ Gams, W (1977). "A key to the species of Mortierella". Persoonia 9: 381–391.

- ↑ Ribes, JA; Vanover-Sams, CL; Baker, DJ (200). "Zygomycetes in Human Disease". Clin Microbiol Rev 13 (2): 236–301. doi:10.1128/cmr.13.2.236. PMID 10756000.

- ↑ Hudson, RJ; Nielsen, O; Bellamy, J; Stephen, C (2010). Veterinary Science (1st ed.). United Kingdom: Eolss Publishing. ISBN 9781848263185.

- ↑ Liu, D (2011). Molecular detection of human fungal pathogens (1st ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 9781439812419.

Wikidata ☰ Q10589376 entry

|