Biology:Namacalathus

| Namacalathus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Genus: | †Namacalathus Grotzinger et al., 2000 |

| Species: | †N. hermanastes

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Namacalathus hermanastes Grotzinger et al., 2000

| |

Namacalathus[lower-alpha 1] is a problematic metazoan fossil occurring in the latest Ediacaran. The first, and only described species, N. hermanastes,[lower-alpha 2] was first described in 2000 from the Nama Group of central and southern Namibia.[1]

A U–Pb zircon age from the fossiliferous rock in Namibia and Oman provides an age for the Namacalathus zone in the range from 549 to 542 Ma, which corresponds to the Late Ediacaran. Alongside Namapoikia and Cloudina, these organisms are the oldest known evidence in the fossil record of the emergence of calcified skeletal formation in metazoans, a prominent feature in animals appearing later in the Early Cambrian. Shore et al. (2021) reported the first three-dimensional, pyritized preservation of soft tissue in Namacalathus hermanastes from the Nama Group (Namibia), and evaluate the implications of this finding for the knowledge of the phylogenetic relationships of this animal; they suggest it is an ancestor of Lophotrochozoan animals such as brachiopods and worms.[2]

There are only five occurrences of Namacalathus (Namibia, Canada , Oman, Siberia, Paraguay) known to date, all of which are found in association with Cloudina fossils.[1][3][4][5][6][7]

Among the late Precambrian fossil assemblage in the Nama group, Namibia, Namacalathus far outnumber Cloudina and other poorly preserved taxa and ichnofossils found in the formation. The Nama Group fossils occur within thrombolitic facies of immense Proterozoic stromatolitic reefs. Namacalathus lived a benthic existence with its stalk attached to the sea floor by means of a holdfast, or possibly to algal mats growing on the reef surface.

Morphology

The skeleton is believed to have consisted of high-magnesium calcite.[8]

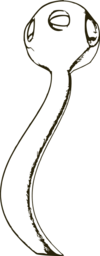

It has a unique shape with a cup on a stalk. The stalk is hollow all the way through and tapered from the bottom, ranging from 1 to 2 mm in diameter, and reaching 30 mm in length. The narrower top of the stalk connects to the cup. The cup is hollow and has a large hole in the top with the shell curving over forming a cup lip. Around the side of the globe are six or seven symmetrically arranged holes, called "windows". The wall curves inwards around each window in a formation called window lips. Each hole is slightly elongated vertically and expanded on the higher side. The size of the cup varies from two to about 25 mm, but averages 6.1 mm. The ratio of the height of the cup to the diameter is from 0.7 to 1.3. The fossil is lightly calcified, preserved as calcite crystals; its original morphology is unknown.[9] The walls in Namacalathus are only 0.1 mm thick, and often deformed by the weight of the sediment. The windows were probably originally filled with organic matter during life, but the cup was likely to be open.

Siberian specimens from the borehole Vostok 3 were designated as new species, because they have, unlike the type species N. hermanastes, a significantly smaller size. Most specimens show sections of the perforated cup, ranging from 110 to 230 μm in diameter; one specimen (with a cup 120 μm across) has a stalk (30 μm in diameter). The walls of the cup are 10 μm thick.[5]

Because the three-dimensional shape of Namacalathus is complex, and the wall is so thin, the fossils appear as a two-dimensional sections in a wide variety of shapes, including closed and open circles, irregular hexagons or heptagons, as well as heart and moon shapes.[10]

Ecology

Namacalathus was an ecological generalist, able to colonise a variety of settings in the mid- to off-ramp environs, adapting its size to suit the local conditions.[11]

Affinity

Namacalathus has typically been considered to represent a cnidarian-grade organism, due in part to its propensity for asexual reproduction by budding. Most recently, however (2015), it been interpreted as a lophophorate based on detailed observations of its skeletal construction, which point to accretionary growth in the manner of brachiopods and bryozoans.[8]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Grotzinger, John P.; Watters, Wesley A.; Knoll, Andrew H. (2000). "Calcified metazoans in thrombolite-stromatolite reefs of the terminal Proterozoic Nama Group, Namibia". Paleobiology 26 (3): 334–359. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0334:CMITSR>2.0.CO;2. http://paleobiol.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/26/3/334.

- ↑ Shore, A. J.; Wood, R. A.; Butler, I. B.; Zhuravlev, A. Yu.; McMahon, S.; Curtis, A.; Bowyer, F. T. (2021). "Ediacaran metazoan reveals lophotrochozoan affinity and deepens root of Cambrian Explosion". Science Advances 7 (1): eabf2933. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abf2933. PMID 33523867. Bibcode: 2021SciA....7.2933S.

- ↑ Amthor, Joachim E.; Grotzinger, John P.; Schröder, Stefan; Bowring, Samuel A.; Ramezani, Jahandar; Martin, Mark W.; Matter, Albert (2003). "Extinction of Cloudina and Namacalathus at the Precambrian-Cambrian boundary in Oman". Geology 31 (5): 431–434. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031<0431:EOCANA>2.0.CO;2. Bibcode: 2003Geo....31..431A.

- ↑ Hofmann, Hans J.; Mountjoy, Eric W. (2001). "Namacalathus-Cloudina assemblage in Neoproterozoic Miette Group (Byng Formation), British Columbia: Canada's oldest shelly fossils". Geology 29 (12): 1091–1094. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<1091:NCAINM>2.0.CO;2. Bibcode: 2001Geo....29.1091H.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kontorovich, A.E.; Varlamov, A.I.; Grazhdankin, D.V.; Karlova, G.A.; Klets, A.G.; Kontorovich, V.A.; Saraev, S.V.; Terleev, A.A. et al. (2008). "A section of Vendian in the east of West Siberian Plate (based on data from the Borehole Vostok 3)". Russian Geology and Geophysics 49 (12): 932–939. doi:10.1016/j.rgg.2008.06.012. Bibcode: 2008RuGG...49..932K.

- ↑ Kontorovich, A. E.; Sokolov, B. S.; Kontorovich, V. A.; Varlamov, A. I.; Grazhdankin, D. V.; Efimov, A. S.; Klets, A. G.; Saraev, S. V. et al. (2009). "The first section of vendian deposits in the basement complex of the West Siberian petroleum megabasin (resulting from the drilling of the Vostok-3 parametric borehole in the Eastern Tomsk region)". Doklady Earth Sciences 425 (1): 219–222. doi:10.1134/S1028334X09020093. Bibcode: 2009DokES.425..219K.

- ↑ Lucas Veríssimo Warren; Fernanda Quaglio; Marcello Guimarães Simões; Claudio Gaucher; Claudio Riccomini; Daniel G. Poiré; Bernardo Tavares Freitas; Paulo C. Boggiani et al. (2017). "Cloudina-Corumbella-Namacalathus association from the Itapucumi Group, Paraguay: Increasing ecosystem complexity and tiering at the end of the Ediacaran". Precambrian Research 298: 79–87. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2017.05.003. Bibcode: 2017PreR..298...79W. https://repositorio.unesp.br/bitstream/11449/163140/1/WOS000407654800005.pdf.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Zhuravlev, A. Yu.; Wood, R. A.; Penny, A. M. (2015). "Ediacaran skeletal metazoan interpreted as a lophophorate". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282 (1818): 20151860. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.1860. PMID 26538593.

- ↑ Porter, S. M. (1 June 2007). "Seawater Chemistry and Early Carbonate Biomineralization". Science 316 (5829): 1302. doi:10.1126/science.1137284. PMID 17540895. Bibcode: 2007Sci...316.1302P.

- ↑ Watters, Wesley A.; Grotzinger, John P. (2001). "Digital reconstruction of calcified early metazoans, terminal Proterozoic Nama Group, Namibia". Paleobiology 27 (1): 159–171. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2001)027<0159:DROCEM>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Penny, A. M.; Wood, R. A.; Zhuravlev, A. Yu.; Curtis, A.; Bowyer, F.; Tostevin, R. (2016). "Intraspecific variation in an Ediacaran skeletal metazoan:Namacalathusfrom the Nama Group, Namibia". Geobiology 15 (1): 81–93. doi:10.1111/gbi.12205. PMID 27677524.

Wikidata ☰ Q554023 entry

|