Biology:Osmotic pressure

Osmotic pressure is the minimum pressure which needs to be applied to a solution to prevent the inward flow of its pure solvent across a semipermeable membrane.[1] It is also defined as the measure of the tendency of a solution to take in its pure solvent by osmosis. Potential osmotic pressure is the maximum osmotic pressure that could develop in a solution if it were separated from its pure solvent by a semipermeable membrane

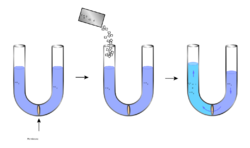

Osmosis occurs when two solutions containing different concentrations of solute are separated by a selectively permeable membrane. Solvent molecules pass preferentially through the membrane from the low-concentration solution to the solution with higher solute concentration. The transfer of solvent molecules will continue until equilibrium is attained.[1][2]

Theory and measurement

Jacobus van 't Hoff found a quantitative relationship between osmotic pressure and solute concentration, expressed in the following equation:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi = icRT }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi }[/math] is osmotic pressure, i is the dimensionless van 't Hoff index, c is the molar concentration of solute, R is the ideal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature (usually in kelvins). This formula applies when the solute concentration is sufficiently low that the solution can be treated as an ideal solution. The proportionality to concentration means that osmotic pressure is a colligative property. Note the similarity of this formula to the ideal gas law in the form [math]\displaystyle{ P = \frac{n}{V} RT = c_\text{gas} RT }[/math] where n is the total number of moles of gas molecules in the volume V, and n/V is the molar concentration of gas molecules. Harmon Northrop Morse and Frazer showed that the equation applied to more concentrated solutions if the unit of concentration was molal rather than molar;[3] so when the molality is used this equation has been called the Morse equation.

For more concentrated solutions the van 't Hoff equation can be extended as a power series in solute concentration, c. To a first approximation,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi = \Pi_0 + A c^2 }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi_0 }[/math] is the ideal pressure and A is an empirical parameter. The value of the parameter A (and of parameters from higher-order approximations) can be used to calculate Pitzer parameters. Empirical parameters are used to quantify the behavior of solutions of ionic and non-ionic solutes which are not ideal solutions in the thermodynamic sense.

The Pfeffer cell was developed for the measurement of osmotic pressure.

Applications

Osmotic pressure measurement may be used for the determination of molecular weights.

Osmotic pressure is an important factor affecting biological cells.[4] Osmoregulation is the homeostasis mechanism of an organism to reach balance in osmotic pressure.

- Hypertonicity is the presence of a solution that causes cells to shrink.

- Hypotonicity is the presence of a solution that causes cells to swell.

- Isotonicity is the presence of a solution that produces no change in cell volume.

When a biological cell is in a hypotonic environment, the cell interior accumulates water, water flows across the cell membrane into the cell, causing it to expand. In plant cells, the cell wall restricts the expansion, resulting in pressure on the cell wall from within called turgor pressure. Turgor pressure allows herbaceous plants to stand upright. It is also the determining factor for how plants regulate the aperture of their stomata. In animal cells excessive osmotic pressure can result in cytolysis.

Osmotic pressure is the basis of filtering ("reverse osmosis"), a process commonly used in water purification. The water to be purified is placed in a chamber and put under an amount of pressure greater than the osmotic pressure exerted by the water and the solutes dissolved in it. Part of the chamber opens to a differentially permeable membrane that lets water molecules through, but not the solute particles. The osmotic pressure of ocean water is approximately 27 atm. Reverse osmosis desalinates fresh water from ocean salt water.

Derivation of the van 't Hoff formula

Consider the system at the point when it has reached equilibrium. The condition for this is that the chemical potential of the solvent (since only it is free to flow toward equilibrium) on both sides of the membrane is equal. The compartment containing the pure solvent has a chemical potential of [math]\displaystyle{ \mu^0(p) }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] is the pressure. On the other side, in the compartment containing the solute, the chemical potential of the solvent depends on the mole fraction of the solvent, [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \lt x_v \lt 1 }[/math]. Besides, this compartment can assume a different pressure, [math]\displaystyle{ p' }[/math]. We can therefore write the chemical potential of the solvent as [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_v(x_v, p') }[/math]. If we write [math]\displaystyle{ p' = p + \Pi }[/math], the balance of the chemical potential is therefore:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_v^0(p)=\mu_v(x_v,p+\Pi). }[/math]

Here, the difference in pressure of the two compartments [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi \equiv p' - p }[/math] is defined as the osmotic pressure exerted by the solutes. Holding the pressure, the addition of solute decreases the chemical potential (an entropic effect). Thus, the pressure of the solution has to be increased in an effort to compensate the loss of the chemical potential.

In order to find [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi }[/math], the osmotic pressure, we consider equilibrium between a solution containing solute and pure water.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_v(x_v,p+\Pi) = \mu_v^0(p). }[/math]

We can write the left hand side as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_v(x_v,p+\Pi)=\mu_v^0(p+\Pi)+RT\ln(\gamma_v x_v) }[/math],

where [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma_v }[/math] is the activity coefficient of the solvent. The product [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma_v x_v }[/math] is also known as the activity of the solvent, which for water is the water activity [math]\displaystyle{ a_w }[/math]. The addition to the pressure is expressed through the expression for the energy of expansion:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_v^o(p+\Pi)=\mu_v^0(p)+\int_p^{p+\Pi}\! V_m(p') \, dp', }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ V_m }[/math] is the molar volume (m³/mol). Inserting the expression presented above into the chemical potential equation for the entire system and rearranging will arrive at:

- [math]\displaystyle{ -RT\ln(\gamma_v x_v)=\int_p^{p+\Pi}\! V_m(p') \, dp'. }[/math]

If the liquid is incompressible the molar volume is constant, [math]\displaystyle{ V_m(p') \equiv V_m }[/math], and the integral becomes [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi V_m }[/math]. Thus, we get

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi = -(RT/V_m) \ln(\gamma_v x_v) . }[/math]

The activity coefficient is a function of concentration and temperature, but in the case of dilute mixtures, it is often very close to 1.0, so

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi = -(RT/V_m) \ln(x_v) . }[/math]

The mole fraction of solute, [math]\displaystyle{ x_s }[/math], is [math]\displaystyle{ 1-x_v }[/math], so [math]\displaystyle{ \ln(x_v) }[/math] can be replaced with [math]\displaystyle{ \ln(1 - x_s) }[/math], which, when [math]\displaystyle{ x_s }[/math] is small, can be approximated by [math]\displaystyle{ -x_s }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi=(RT/V_m)x_s. }[/math]

The mole fraction [math]\displaystyle{ x_s }[/math]is [math]\displaystyle{ n_s/(n_s+n_v) }[/math]. When [math]\displaystyle{ x_s }[/math]is small, it may be approximated by [math]\displaystyle{ x_s = n_s/n_v }[/math]. Also, the molar volume [math]\displaystyle{ V_m }[/math] may be written as volume per mole, [math]\displaystyle{ V_m = V/n_v }[/math]. Combining these gives the following.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi = cRT. }[/math]

For aqueous solutions of salts, ionisation must be taken into account. For example, 1 mole of NaCl ionises to 2 moles of ions.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Fundamentals of Biochemistry (Rev. ed.). New York: Wiley. 2001. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-471-41759-0.

- ↑ "Section 5.5 (e)". Physical Chemistry (9th ed.). Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-954337-3.

- ↑ "The Osmotic Pressure of Concentrated Solutions and the Laws of the Perfect Solution.". Journal of the American Chemical Society 30 (5): 668–683. 1908-05-01. doi:10.1021/ja01947a002. ISSN 0002-7863. https://zenodo.org/record/1428858. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ↑ "Poroelastic osmoregulation of living cell volume" (in English). iScience 24 (12): 103482. December 2021. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103482. PMID 34927026. Bibcode: 2021iSci...24j3482E.

External links

|