Biology:Osmundastrum pulchellum

| Osmundastrum pulchellum | |

|---|---|

| |

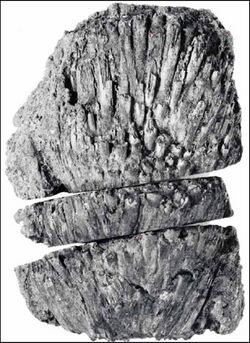

| Holotype rhizome | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Polypodiophyta |

| Class: | Polypodiopsida |

| Order: | Osmundales |

| Family: | Osmundaceae |

| Genus: | Osmundastrum |

| Species: | †O. pulchellum

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Osmundastrum pulchellum (Bomfleur, B., Grimm, G. W., & McLoughlin, S.) C.Presl

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Osmunda pulchella Bomfleur, B., Grimm, G. W., & McLoughlin, S., 2015 | |

Osmundastrum pulchellum is an extinct species of Osmundastrum, leptosporangiate ferns in the family Osmundaceae from the lower Jurassic (Pliensbachian-Toarcian?) Djupadal Formation of Southern Sweden.[1][2][3][4] It remained unstudied for 40 years.[5] It is one of the most exceptional fossil ferns ever found, preserving intact calcified (thus dead) tissue with DNA and cells.[3] Its exceptional preservation has allowed the study of the DNA relationships with extant Osmundaceae ferns, proving a 180-million-year genomic stasis.[3] It has also preserved its biotic interactions and even ongoing mitosis.[6][7][1][2]

History and discovery

The only known specimen was recovered at the mafic pyroclastic and epiclastic deposits of the Djupadal Formation, dated Pliensbachian-Toarcian(?), that are present near Korsaröd Lake, at the north of Höör, central Skåne, southern Sweden.[2] The location was studied first by Gustav Andersson, a local farmer, who was a passionate follower of scientific discoveries.[5] Through his interest in geology, he identified several coeval volcanic plugs, and motivated by the presence of volcanic soils, he excavated a location at the south of the Korsaröd lake.[5] Initially nothing was found, but a second deeper dig revealed a series of aggregated wood remains on volcanic lahar-derived stones.[5] Samples taken from the location were sent to the geologist Hans Tralau, who carried out palynological research on them, estimating an age of deposition of Late Toarcian-Aalenian(?).[8] A petrified rhizome was sent to Tralau, who understood the significance of the fossil and intended to publish it formally, but his untimely death in March 1977 made it impossible.[5] The rhizome, along with the fossil wood, was archived at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, where the geologist Britta Lundblad tried also to publish it formally, what was also impossible due to her retirement in 1986.[5] The fossil was lying forgotten in the archives of the museum until 2013, when it was discovered again and studied, finding that it preserved spectacular cellular detail, rarely seen on fossils.[5] In 2015, it was finally published as Osmunda pulchella by B. Bomfleur, G. W. Grimm and S. McLoughlin.[2][3][4][9] The specific epithet pulchella (Latin diminutive of pulchra, 'beautiful', 'fair;) was chosen in reference to the exquisite preservation and aesthetic appeal of the holotype specimen.[2] The name Osmunda pulchella was mostly used in the main publications referring to it until in 2017 a revision of the cladistic status of the fossil Osmundales showed that the fossil was in fact a member of the genus Osmundastrum, so it became Osmundatrum pulchellum.[1]

Description

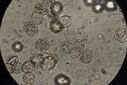

The Osmundastrum pulchellum holotype is a calcified rhizome fragment about 6 cm long and up to 4 cm in diameter that probably come from a small (approx. 50 cm tall) fern.[6] It is composed of a small central stem surrounded by a compact mantle of helically arranged petiole bases and interspersed rootlets that extend outwards perpendicular to the axis, indicating a low rhizomatous rather than arborescent growth.[2] This, together with the asymmetrical distribution of the roots, points to a creeping habit.[2] The stem is around about 7.5 mm in diameter and the pith about 1.5 mm in diameter and entirely parenchymatous.[2] In the pith, cell walls lack the presence of an internal endodermis or internal phloem, considered to be an original feature, rather than a loss due to inadequate preservation.[2] Traces of leaves and associated rootlets are present traversing the outer cortex.[2] This specimen is well known for the quality of its preservation, quality revealing cellular and subcellular detail: from tracheids with preserved wall thickenings, to parenchyma cells containing preserved cellular contents.[2] Some of the parenchyma cells contain oblate particles about 1–5 μm in diameter, interpreted as putative amyloplasts.[2]

Classification

The exceptional preservation of Osmundastrum pulchellum has allowed the establishment of an evolutionary overview of royal ferns since the lower Jurassic.[2][3][9] At its description as Osmunda pulchella, it was compared with Todea, Leptopteris, Plenasium and Claytosmunda, and found as a bridge in the morphological gap between extant Osmundastrum and the subgenus Osmunda inside Osmunda – the closest species to Osmundastrum.[2] It was shown that this species and the extant Osmundaceae share the same chromosome count and DNA content.[3] In 2017, a re-examination of the phylogeny of the fossil Osmundales showed it to be a member of the genus Osmundastrum and a probable precursor of the modern Osmundastrum cinnamomeum.[1] Latter, a new species, Osmundastrum gvozdevae from the Middle Jurassic of the Russian Kursk Region was recovered as a possible sister taxon.[10]

Biology

Osmundastrum pulchellum is well known thanks to exceptional preservation of detailed anatomical structures (e.g., pith, stele, petiole base, adventitious roots, and even nuclei). As well is the only known case of fossilized ongoing mitosis.[7] This is shown by the fact that the chromosomes and cell nuclei show marked structural heterogeneities compared to the cell walls during different stages of the cell cycle.[7] A rapid calcite permineralization "froze" the organic molecules in time, which suggests the fern rhizome was fossilized probably on a very short time, perhaps even minutes thanks to a fast lahar deposit.[7] The tissues show cells with nuclei, nucleoli, and chromosomes during the interphase, prophase, prometaphase, and possible anaphase of the cell cycle.[11] Some cells also show pyknotic nuclei typical of cells undergoing apoptosis (programmed cell death).[11] The subcellular detail is nearly unique, as other ferns preserved in similar conditions lack them, for example Ashicaulis liaoningensis.[12] Several biotic interactions were recovered on the rhizome. Exotic roots were recovered on the petiole bases, with a level of preservation that matches that of the whole plant, bearing a similar vasculature as seen in modern lycophytes. They are interpreted as belonging to a small herbaceous epiphytic lycopsid, with its megaspores also linked with the specimen.[6] Other sporangial fragments from other ferns (Deltoidospora toralis, Cibotiumspora jurienensis, etc.) were also recovered, known from the nearby deposits.[13] A similar community was recovered on a Todea rhizome from the early Eocene of Patagonia, but with the epiphytic plants being in Osmundastrum pulchellum exclusively lycopsids and ferns, which may indicate that bryophytes had not yet evolved the epiphytic habit during the Jurassic.[14] Possible oogonia of Peronosporomycetes are found in a parasitic or saprotrophic relation with the plant. If the identification of the oogonia of Peronosporomycetes is correct, then this implies regularly moist conditions for the growth of Osmundastrum pulchellum.[6] Thread-like structures were found, identified as derived from a pathogenic or saprotrophic fungus invading necrotic tissues of the host plant. The interaction of the fungus with the plant was probably mycorrhizal.[6] Excavations up to 715 μm in diameter are evident, filled with pellets that resemble the coprolites of oribatid mites, found also in Paleozoic and Mesozoic woods.[6]

Paleoenvironment

The Djupadal Formation was deposited in the Central Skane region, linked to the late Early Jurassic Volcanism. Several coeval Volcanic necks are recovered on the region, such as Eneskogen (A large hill covered by quaternary sediments. Some few boulders and basalt pillars were exposed), Bonnarp (5–6 m height and covers roughly 5,000 square meters, covered by Jurassic sediments) and Säte (Comprise two basalt pipes, each roughly 6–10 m high and some 10,000 square meters in area).[15] The Korsaröd member includes a volcanic-derived lagerstatten where this fern was found, probably derived from a fast lahar deposition.[13] Thanks to the data provided by the fossilized wood rings, it was found that the location of Korsaröd hosted a middle-latitude Mediterranean-type biome in the late Early Jurassic, with low rainfall. Superimposed on this climate were the effects of a local active Strombolian Volcanism and hydrothermal activity.[13] This location has been compared with modern Rotorua, New Zealand, considered an analogue for the type of environment represented in southern Sweden at this time.[4] The locality was populated mostly by Cupressaceae trees (including specimens up to 5 m in circunference), known thanks to the great abundance of the wood genus Protophyllocladoxylon and the high presence of the genus Perinopollenites elatoides (also Cupressaceae) and Eucommiidites troedsonii (Erdtmanithecales).[13] The underlying Höör Sandstone Formation hosts abundant Chasmatosporites spp. pollen produced by plants related to cycadophytes, while the Djupadal volcanogenic deposits are dominated by cypress family pollen with an understorey component rich in putative Erdtmanithecales, both representing vegetation of disturbed habitats. The abundance of Protophyllocladoxylon sp. is also related with a sporadic intraseasonal and multi-year episodes of growth disruption, probably due to the volcanic action.[13] Pollen, spores, wood and charcoal locally indicate a complex forest community subject to episodic fires and other forms of disturbance in an active volcanic landscape under a moderately seasonal climate.[6] Osmundastrum pulchellum was a prominent understorey element in this vegetation and was probably involved in various competitive interactions with neighboring plant species, such as lycophytes, whose roots have been recovered inside the rhizome.[6] The ferns were part of a fern- and conifer-rich vegetation occupying a topographic depression in the landscape (moist gully) that was engulfed by one or more lahar deposits.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Bomfleur, B.; Grimm, G. W.; McLoughlin, S. (2017). "The fossil Osmundales (royal ferns)—a phylogenetic network analysis, revised taxonomy, and evolutionary classification of anatomically preserved trunks and rhizomes". PeerJ 5: e3433. doi:10.7717/peerj.3433. PMID 28713650.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Bomfleur., B.; Grimm, G. W.; McLoughlin., S. (2015). "Osmunda pulchella sp. nov. from the Jurassic of Sweden—reconciling molecular and fossil evidence in the phylogeny of modern royal ferns (Osmundaceae)". BMC Evolutionary Biology 15 (1): 126. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0400-7. PMID 26123220.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Bomfleur, B.; McLoughlinVajda, V. (2014). Fossilized nuclei and chromosomes reveal 180 million years of genomic stasis in royal ferns. Science, 343(6177), 1376-1377, S.; Vajda, V. (2014). "Fossilized nuclei and chromosomes reveal 180 million years of genomic stasis in royal ferns". Science 343 (6177): 1376–1377. doi:10.1126/science.1249884. PMID 24653037. Bibcode: 2014Sci...343.1376B. https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/science.1249884. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Vajda, V.; McLoughlin, S.; Bomfleur, B. (2014). "Fossilfyndet i Korsaröd". Geologiskt Forum-Geological Society of Sweden 82 (1): 24–29. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267865986. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 McLoughlin, S.; Bomfleur, B.; Vajda, V. (2014). "A phenomenal fossil fern, forgotten for forty years". Deposits Magazine 40 (1): 16–21. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267866115. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 McLoughlin, S.; Bomfleur, B. (2016). "Biotic interactions in an exceptionally well preserved osmundaceous fern rhizome from the Early Jurassic of Sweden". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 464 (1): 86–96. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.01.044. Bibcode: 2016PPP...464...86M.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Qu, Y.; McLoughlin, M.; van Zuilen, M. A.; Whitehouse, M.; Engdahl, A.; Vajda, V. (2019). "Evidence for molecular structural variations in the cytoarchitectures of a Jurassic plant". Geology 47 (4): 325–329. doi:10.1130/g45725.1. Bibcode: 2019Geo....47..325Q.

- ↑ Tralau, H.,1973 : En palynologisk åldersbestämning av v ulkanisk aktivitet i Skåne. -Fauna och Flora, 68, pp .12 1- 176. S tockholm.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Bomfleur, B.; Grimm, G. W.; McLoughlin, S. (2014). "A fossil Osmunda from the Jurassic of Sweden—reconciling molecular and fossil evidence in the phylogeny of Osmundaceae". bioRxiv: 005777. doi:10.1101/005777. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/005777v1. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ↑ Bazhenova, N. V.; Bazhenov, A. V. (2019). "Stems of a New Osmundaceous Fern from the Middle Jurassic of Kursk Region, European Russia". Paleontological Journal 53 (5): 540–550. doi:10.1134/S0031030119050034. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1134/S0031030119050034. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Bailleul, A. M. (2021). "Fossilized cell nuclei are not that rare: Review of the histological evidence in the Phanerozoic". Earth-Science Reviews 216 (6): 103. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103599. Bibcode: 2021ESRv..21603599B. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350941252. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ Tian, N.; Wang, Y. D.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, S. L; Zhu, Z. P.; Liu, Z. J. (2018). "Permineralized osmundaceous and gleicheniaceous ferns from the Jurassic of Inner Mongolia, NE China". Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments 98 (1): 165–176. doi:10.1007/s12549-017-0313-0. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322690839. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Vajda, V.; Linderson, H.; McLoughlin, S. (2016). "Disrupted vegetation as a response to Jurassic volcanism in southern Sweden.". Geological Society, London, Special Publications 434 (1): 127–147. doi:10.1144/SP434.17. Bibcode: 2016GSLSP.434..127V. https://sp.lyellcollection.org/content/434/1/127. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ↑ Bippus, A. C.; Escapa, I. H.; Wilf, P.; Tomescu, A. M. (2019). "Fossil fern rhizomes as a model system for exploring epiphyte community structure across geologic time: evidence from Patagonia". PeerJ 7: e8244. doi:10.7717/peerj.8244. PMID 31844594.

- ↑ Bergelin, I. (2009). "Jurassic volcanism in Skåne, southern Sweden, and its relation to coeval regional and global events". GFF 131 (1): 165–175. doi:10.1080/11035890902851278.

Wikidata ☰ Q105834558 entry

|