Biology:Perdita meconis

| Perdita meconis | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Andrenidae |

| Genus: | Perdita |

| Species: | P. meconis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Perdita meconis Griswold, 1993

| |

Perdita meconis, the Mojave poppy bee, is a rare bee species that was described in 1993.[2] The Mojave poppy bee has been petitioned for protection under the Endangered Species Act due to pressures in their native range such as invasive species, habitat fragmentation, gypsum mining, and climate change.[3] [4]

Overview

The Mojave poppy bee is a solitary bee that is a part of the genus Perdita and is native to the Mojave Desert. The Mojave poppy bee is oligolectic, like other Perdita species, having a mutualistic relationship with plants in a single genus, the Las Vegas bear poppy and the dwarf bear-poppy.[5] This relationship is in part how they got their name as the Latin word for poppy is "mecon".[2] It's genome has recently been sequenced as part of the Beenome100 project. [6]

Description

Males

Male Mojave poppy bees are relatively small with a body length of 5 mm, and 4 mm forewings. They have a dark green head that is wider than it is long, with light yellow mandibles and face (below the antennae). They have mostly black legs with light yellow around the leg joints and stripes on the front of their lower legs. Furthermore, the abdominal terga of Mojave poppy bees have several distinct characteristics including a dark green to brown region on T1 (closest to the thorax), T2 features a yellow stripe with dark brown spots, T3 is similar with less definition in the spots, T4 is amber in color with slightly lighter spots that lack definition, T5-7 are amber. T7 (furthest from the thorax) has a unique shape featuring a thickened apical projection.[2]

Females

Female Mojave poppy bees are difficult to distinguish from other Perdita.[2][3] Female Mojave poppy bees are slightly larger than their male counterparts with a body length of 6.5–7 mm, and 4.5–5 mm forewings. Their heads share the same color scheme as the male Mojave poppy bees, however the pale yellow is less extensive. Their legs are dark brown with light yellow on their front legs. Their terga are colored differently than the males with T1 and T2 having a dark brown color with a green cast and a basal stripe. T3 and T4 are similar with wider basal stripes. T5 is yellow except for a defined spot.[2]

Habitat

Range

The Mojave poppy bee's former range included the southwest corner of Utah, northwest region of Arizona and the Southern region of Nevada (near Las Vegas). Now there is no evidence that the Mojave poppy bee remains in Utah. It is presumed that the populations that inhabited the area around St George have died out.[7] Some evidence suggests one of the reasons that the Mojave poppy bee was pushed to extinction in Utah could be due to the invasion of Africanized honey bees.[4][8] The current range has been reduced to seven known, highly fragmented, sites in Nevada. There was only a single historical report of this bee in Arizona, and this region is devoid of populations at this time.[3] For this reason the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service considers the possible range of the Mojave poppy bee to be limited to Nevada.[9]

Host plants

The Mojave poppy bee does not switch flowers, meaning its range is limited to where their preferred poppies grow, and where adequate nesting substrate is available. The Mojave poppy bee lives in the gypsum substrate in which their preferred poppies, the dwarf bear-poppy and Las Vegas bear-poppy, grow.[3][5][2] The dwarf bear-poppy has been listed as an endangered species since 1979[5] and remains listed on the endangered species list today.[10] The Las Vegas bear-poppy has been submitted for protection under the endangered species act. This petition for protection is currently under review.[11]

Environmental stress

Invasive species

As noted prior, there is evidence that the introduction of the invasive Africanized honey bees pushed the Mojave poppy bee to extirpation in Utah.[4][8] Africanized bees continue to threaten the remaining Mojave poppy bee colonies as they continue to invade the regions where the Mojave poppy bee still survives.[12] It is thought that the reason that the Mojave poppy bee has withstood the invasion of Africanized bees in Nevada is due to a difference in livestock grazing practices between Utah and the other locations.[8]

Africanized bees have thus far filled the niche of the Mojave poppy bee in Utah, pollinating the bear-poppies.[5] This indicates that the continued proliferation of the highly successful Africanized honey bees in Mojave poppy bee habitat remains a threat to the protection of this rare species.[3]

Habitat fragmentation and loss of gene flow

One of the major threats to the Mojave poppy bee is habitat fragmentation which can be caused by urbanization of previously wild landscapes. Urbanization in the Mojave poppy bee's habitat is happening quickly, resulting in habitat fragmentation; because of the poppy bee's small flight radius, the bees become isolated and cannot maintain gene flow between the smaller populations.[3] It is thought that the smaller isolated populations could have been a much larger more connected metapopulation that has now been fragmented.[8]

Dwindling of poppies and gypsum mining

The dwindling of the Mojave poppy bee's preferred poppies has been more pronounced because recent efforts to urbanize the desert landscape involve uprooting the plants to facilitate urban expansion. However, another threat to the poppies and the Mojave poppy bee is gypsum mining. There are three gypsum mines in the bees' range that dig up the gypsum substrate that the poppies grow in and that the bees nest in.[3] The Bureau of Land Management approved expansion of gypsum mining in 2018 despite the endangered status of the poppy species and the importance of this habitat for the Mojave poppy bee.[13][3]

Climate change

Climate change has placed stress on the bear-poppies' life cycle and the Mojave poppy bee's life cycle, by causing a disconnect between flowering times and active periods in bee populations.[3]

Endangered Species Act

Application

In 2018 an application for the Mojave poppy bee to be protected under the Endangered Species Act was penned and submitted. The petition cited gypsum mining, urbanization, habitat fragmentation, climate change, invasive species, and disease/predation as reasons for protection. The petition also called for the remaining poppy bee habitat to be designated a critical habitat that needs to be protected for the continued survival of the Mojave poppy bee.[3]

Current status

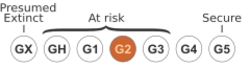

The application was placed under consideration in 2019 by the Environmental Protection Agency, however they have yet to make a decision to accept or reject the protection of the Mojave poppy bee or their habitat.[9] Despite the delay in the verdict under the Endangered Species Act there is a general consensus that Perdita meconis is vulnerable to, or under threat of, extinction.[7]

References

- ↑ "Perdita meconis". NatureServe. https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.114779/Perdita_meconis. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Griswold, Terry (1993). "New species of Perdita (Pygoperdita) Timberlake of the P. californica species group (Hymenoptera)". Pan-Pacific Entomologist 69 (2): 183–189.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 Cornelisse, T. (2018). Petition to list the Mojave poppy bee (Perdita meconis) under the Endangered Species Act and concurrently designate critical habitat. Center for Biological Diversity.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Tripodi, Amber D.; Tepedino, Vincent J.; Portman, Zachary M. (2019-12-01). "Timing of Invasion by Africanized Bees Coincides with Local Extinction of a Specialized Pollinator of a Rare Poppy in Utah, USA" (in en). Journal of Apicultural Science 63 (2): 281–288. doi:10.2478/jas-2019-0019. ISSN 2299-4831.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 DeNittis, Alyson M.; Meyer, Susan E. (2021-12-21). "Reproductive Success of an Endangered Plant after Invasive Bees Supplant Native Pollinator Services". Diversity 14 (1): 1. doi:10.3390/d14010001. ISSN 1424-2818.

- ↑ Schweizer, Rena M; Meidt, Colleen G; Benavides, Ligia R; Wilson, Joseph S; Griswold, Terry L; Sim, Sheina B; Geib, Scott M; Branstetter, Michael G (2024-07-10). Shapiro, Beth. ed. "Reference genome for the Mojave poppy bee ( Perdita meconis ), a specialist pollinator of conservation concern" (in en). Journal of Heredity 115 (4): 470–479. doi:10.1093/jhered/esad076. ISSN 0022-1503. PMID 38088446. PMC 11235129. https://academic.oup.com/jhered/article/115/4/470/7471740.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.114779/Perdita_meconis.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Portman, Zachary M.; Tepedino, Vincent J.; Tripodi, Amber D.; Szalanski, Allen L.; Durham, Susan L. (2018). "Local extinction of a rare plant pollinator in Southern Utah (USA) associated with invasion by Africanized honey bees" (in en). Biological Invasions 20 (3): 593–606. doi:10.1007/s10530-017-1559-1. ISSN 1387-3547. Bibcode: 2018BiInv..20..593P. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10530-017-1559-1.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "ECOS: Species Profile". https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/species/10757.

- ↑ "ECOS: Species Profile". https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/species/5492.

- ↑ "ECOS: Species Profile". https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/species/7225.

- ↑ "USDA Map of Africanized Honey Bee Spread Updated : USDA ARS". https://www.ars.usda.gov/news-events/news/research-news/2007/usda-map-of-africanized-honey-bee-spread-updated/.

- ↑ Bureau of Land Management. 2018. Environmental Assessment: Lima Nevada Gypsum Quarry Plan of Operations. Environmental Assessment DOI-BLM-NV-S010-2013-0024-EA N-91107. United States Department of the Interior.

Wikidata ☰ Q2209934 entry

|