Biology:Persian leopard

| Persian leopard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. p. tulliana

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera pardus tulliana (Valenciennes, 1856)

| |

| |

| Distribution of Persian leopard (in green) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

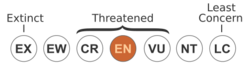

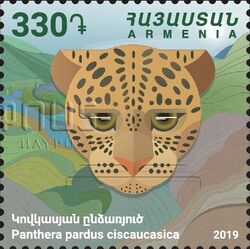

The Persian leopard, also known as the Caucasian leopard[2] is a leopard population in the Caucasus, Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia. The Persian leopard was previously considered a distinct subspecies, Panthera pardus saxicolor or Panthera pardus ciscaucasica,[2] but is now assigned to the subspecies Panthera pardus tulliana, which also includes the Anatolian leopard in Turkey.[3] The Persian leopard is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List, as the population is estimated at fewer than 871–1,290 mature individuals and considered declining.[1]

A phylogenetic analysis suggests that the Persian leopard matrilineally belongs to a monophyletic group that diverged from African and Arabian leopards in the second half of the Pleistocene.[4]

Taxonomy

Felis tulliana was the scientific name proposed by Achille Valenciennes in 1856 who described a leopard skin and skull from the area of Smyrna in western Turkey.[5] Felis ciscaucasica was proposed by Konstantin Alekseevich Satunin in 1914 based on a leopard specimen from the Kuban region of the North Caucasus.[6] Panthera pardus saxicolor was proposed by Reginald Innes Pocock in 1927 who described leopard skins from different areas of Persia, but recognized their similarity to Caucasian leopard skins.[7] Pocock also described a single skin and two skulls from the Kirthar Mountains in Balochistan as P. p. sindica in 1930. He admitted that the skin closely resembles those of P. p. saxicolor, but are distinguishable from the typical P. p. fusca in colour.[8] It was subsumed to P. p. saxicolor based on molecular genetic analysis in 1996.[9][10]

Today, these names are considered synonyms.[11] Results of a phylogenetic analysis suggests that the Persian leopard matrilineally belongs to a monophyletic group that diverged from a group of Asian leopards in the second half of the Pleistocene.[4]

Characteristics

The Persian leopard varies in colouration; both pale and dark individuals occur in Iran.[12] Its medium body length is 158 cm (62 in), including a 192 mm (7.6 in) long skull and with a 94 cm (37 in) long tail.[13] It weighs up to 60 kg (130 lb).[14]

Biometric data collected from 25 female and male individuals in various provinces of Iran indicates average body length of 259 cm (102 in). A young male from northern Iran weighed 64 kg (141 lb).[15]

Distribution and habitat

The Persian leopard was most likely distributed over the whole Caucasus, except for steppe areas. During surveys conducted between 2001 and 2005 no leopard was recorded in the western part of the Greater Caucasus; it probably survived only at a few sites in the eastern part. The largest population survives in the Alborz and Zagros mountains of Iran.[16] The political and social changes in the former Soviet Union in 1992 caused a severe economic crisis and a weakening of formerly effective protection systems. Ranges of all wildlife were severely fragmented. The former leopard range declined enormously as leopards were persecuted and wild ungulates hunted. Inadequate baseline data and lack of monitoring programmes make it difficult to evaluate declines of mammalian prey species.[17]

As of 2008, of the estimated 871–1,290 mature leopards:[18]

- 550–850 live in Iran, which is the leopard's stronghold in Southwest Asia;[12]

- about 200–300 survive in Afghanistan, where their status is poorly known;

- about 78–90 live in Turkmenistan;

- fewer than 10–13 survive in Armenia;

- fewer than 10–13 survive in Azerbaijan;

- fewer than 10 survive in the Russian North Caucasus;

- fewer than 5 survive in Turkey;[19]

- fewer than 5 survive in Georgia;

- about 3–4 survive in Nagorno-Karabakh.

The Persian leopard avoids areas with long-duration snow cover and areas that are near urban development.[20] Its habitat consists of subalpine meadows, broadleaf forests and rugged ravines from 600–3,800 m (2,000–12,500 ft) in the Greater Caucasus, and rocky slopes, mountain steppes, and sparse juniper forests in the Lesser Caucasus and Iran.[16] Only some small and isolated populations remain in the whole ecoregion. Suitable habitat in each range country is limited and most often situated in remote border areas. Local populations depend on immigration from source populations in the south, mainly in Iran.[21]

Turkey

The Anatolian leopard was considered to have been native to southwestern Turkey, but it is not sure whether leopards survived in this area.[1] The first camera trap photograph of a leopard in the country was obtained in September 2013 in Trabzon Province.[22] Between 2001 and 2013, at least three leopards were killed by local people in southeastern Turkey including one in Çınar district of Diyarbakır Province.[23] In February 2008, a leopard was recorded in Bitlis Province.[24]

North Caucasus

In April 2001, an adult female was shot on the border to Kabardino-Balkaria, her two cubs captured and taken to the Novosibirsk Zoo in Russia.[11] During surveys in the Caucasus in 2007, the presence of leopards was documented. This population was estimated to comprises less than 50 individuals.[16]

In the North Caucasus, signs of leopard presence were found in the upper Andiyskoe and Avarskoye Koisu rivers in Dagestan. In Ingushetia, Ossetia, and Chechnya local people reported the presence of leopards, but no leopard is known to occur in the Western Caucasus.[21]

In 2016, three leopards were released in the Caucasus Nature Reserve in an attempt to reintroduce the species in its historical habitat.[25] Later that year, the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment signed an agreement with Azerbaijan on the creation of a trans-border reserve between the Tlyaratinsky District and the Zagatala State Reserve aimed at the reintroduction of the Persian leopard in the area.[26]

Georgia

Since 1954, leopards were thought to be extinct in Georgia – killed by hunters.[11] There have been several sightings of leopards around the Tbilisi area and in the Shida Kartli province to the northwest of the capital. Leopards live primarily in dense forests, although several have been spotted in the lowland plains in the southeastern region of Kakheti in 2004.[27] Leopard signs have also been found at two localities in Tusheti, the headwaters of the Andi Koysu and Assa rivers bordering Dagestan.[21]

In the winter of 2003, zoologists found footprints of a leopard in Vashlovani National Park in southeastern Georgia. Camera traps recorded one young male individual several times.[28] This individual has not been recorded again between 2009 and 2014.[29]

Armenia

In Armenia, people and leopards have co-existed since early prehistoric times. By the mid-20th century leopards were relatively common in the country's mountains.[30] Between October 2000 and July 2002, tracks of 10 leopards were found in an area of 780 km2 (300 sq mi) in the rugged and cliffy terrain of Khosrov State Reserve, located southeast of Yerevan on the southwestern slopes of the Gegham mountains.[31][32] Leopards were known to live on the Meghri Ridge in the extreme south of Armenia, where only one individual was camera trapped between August 2006 and April 2007, and no signs of other leopards were found during track surveys conducted over an area of 296.9 km2 (114.6 sq mi). The local prey base could support 4–10 individuals, but poaching and disturbance caused by livestock breeding, gathering of edible plants and mushrooms, deforestation and human-induced wild fires were so high that they exceed the tolerance limits of leopards.[33] During surveys in 2013–2014, camera traps recorded leopards in 24 locations in southern Armenia, of which 14 are located in the Zangezur Mountains.[29] This trans-boundary mountain range provides important breeding habitat for leopards in the Lesser Caucasus.[34]

The leopard protection program is implemented by the Ministry of Nature Protection of Armenia in cooperation with WWF Armenia since 2002. It aims at increasing the population and protecting both habitat and main prey species, such as the bezoar ibex and the Armenian mouflon.[35]

Azerbaijan

In 2001, hunting leopards was banned in Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, and anti-poaching activities were regularly conducted in southern Armenia since 2003. Since 2005, seven protected areas have been established in the Lesser Caucasus covering an area of 1,940 km2 (750 sq mi), and three in the Talysh Mountains with an area of 449 km2 (173 sq mi). The total protected area in the country now amounts to 4,245 km2 (1,639 sq mi).[29]

Leopards also survived in northwestern Azerbaijan in the Akhar-Bakhar section of Ilisu State Reserve in the foothills of the Greater Caucasus, but in 2007 numbers were thought to be extremely low.[21]

In March 2007 and in October 2012, an individual was photographed by a camera trap in Hirkan National Park.[36][37] This protected area in southeastern Azerbaijan is located in the Talysh Mountains, which are contiguous with the Alborz Mountains in Iran. During surveys in 2013–2014, camera traps recorded leopards in five locations in Hirkan National Park.[29] The first male leopard crossing from Hirkan National Park into Iran was documented in February 2014. It was killed in the Chubar Highlands in north-western Iran's Gilan Province by a local hunter. This incident indicates that the Talysh Mountains are an important corridor for trans-boundary movement of leopards.[38]

In September 2012, the first female leopard was photographed in Zangezur National Park close to the international border with Iran.[39] During surveys in 2013–2014, camera traps recorded leopards in seven locations in Zangezur National Park, including two different females and one male. All sites are close to the international border with Iran.[29] Five cubs were documented in two sites in the Lesser Caucasus and the Talysh Mountains.[40] Between July 2014 and June 2018, four leopards were identified in the Talysh Mountains and 11 in the trans-boundary region of Nakhchivan and southern Armenia.[41]

Iran

In Iran, leopards were recorded in 74 of 204 protected areas.[42] They are more abundant in the northern than in the southern part of the country.[12] The Hyrcanian forests located in the north and along the Alborz mountain chain are considered as one of the most important habitats for leopards in the country. Their habitat comprises climates with temperatures ranging from −23 °C (−9 °F) to 49 °C (120 °F), but most leopards were recorded in habitats with temperatures of 13 to 18 °C (55 to 64 °F), maximum 20 days of ice cover per year and rainfall of more than 200 mm (7.9 in) per year.[43] The Central Alborz Protected Area covering more than 3,500 km2 (1,400 sq mi) is one of the largest reserves in the country where leopards roam.[44] Evidence for breeding of leopards was documented in six localities inside protected areas located in the Iranian part of the Lesser Caucasus.[34]

In Bamu National Park located northeast in Fars Province, camera trapping carried out from autumn 2007 to spring 2008 revealed seven individuals in a sampling area of 321.12 km2 (123.99 sq mi).[45]

In northeastern Iran, four leopard families with two cubs each were identified during a survey carried out from 2005 to 2008 in Sarigol National Park. A male leopard was photographed in January 2008 spraying urine on a Berberis tree; he was photographed several times until mid-February 2008 in the same area.[46] Camera trapping surveys in summer 2016 documented the presence of 52 leopards in Sarigol, Salouk and Tandooreh National Parks. These included 10 cubs in seven families, thus highlighting that the Kopet Dag and Aladagh Mountains constitute important leopard refugia in the Middle East.[47]

Iraq

Leopards were sporadically recorded in northern Iraq.[48] In October 2011 and January 2012, a leopard was photographed by a camera trap on Jazhna Mountain, located in the Zagros Mountains forest steppe in Iraqi Kurdistan, northern Iraq.[49] Between 2001 and 2014, at least nine leopards were killed by local people in this region.[23]

Turkmenistan

Leopards were recorded by camera traps in the Badkhyz Nature Reserve in the country's south-west.[50] Between September 2014 and August 2016, two radio-collared leopards moved from Iran's Kopet Dag region into Turkmenistan, revealing that the leopard population in the two countries is connected.[51] In 2017, a young male leopard from Iran's Tandoureh National Park dispersed to and settled in Turkmenistan. [52] In October 2018, Iran Environment and Wildlife Watch reported that an old male Persian leopard had moved 20 km (12 mi) from Iran to Turkmenistan.[53]

Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, the leopard is thought to inhabit the central highlands, such as the Hindu Kush and the Wakhan corridor.[54] But photographic evidence for the presence of leopards in these areas does not exist. One individual was recorded by a camera-trap in Bamyan Province in 2011. The long-lasting conflict in the country badly affected both predator and prey species, so that the national population is considered to be small and severely threatened.[55] Between 2004 and 2007, a total of 85 leopard skins were seen being offered in markets of Kabul.[56]

Behaviour and ecology

The diet of the Persian leopard varies depending on habitat.[57][58] In Iran and southern Armenia, it preys foremost on ungulates such as wild goat (Capra aegagrus), mouflon (Ovis orientalis), wild boar (Sus scrofa), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and goitered gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa). It also preys on smaller mammals such as Indian crested porcupine (Hystrix indica) and European hare (Lepus europaeus).[19][59] It occasionally attacks livestock and herding dogs. In Iran, the presence of leopards is highly correlated with the presence of wild goat and wild sheep. An attack by a leopard on an onager (Equus hemionus) was also recorded.[60]

Threats

The Persian leopard is threatened by poaching, depletion of prey base due to poaching, human disturbance such as presence of military and training of troops in border areas, habitat loss due to deforestation, fire, agricultural expansion, overgrazing, and infrastructure development.[1]

In Iran, primary threats are habitat disturbances, illegal hunting and excess of livestock in leopard habitats. Outside protected areas, leopards are unlikely to persist.[61] Droughts in wide areas of leopard habitats affected main prey species such as wild goat and wild sheep.[62] An assessment of leopard mortality in Iran revealed that 71 leopards were killed between 2007 and 2011 in 18 provinces; 70% were hunted or poisoned illegally, and 18% died in road accidents.[63] Between 2000 and 2015, 147 leopards were killed in the country. More than 60% of them died due to poaching, through poisonous bait, and were shot by rangers, trophy hunters and military forces. About 26% of them died in road accidents. More males than females were killed.[64]

In the 1980s, anti-personnel mines were deployed along the northern part of the Iran-Iraq border to deter people from entering the area. Persian leopards roaming this area are safe from poachers and efforts for industrial development, but at least two individuals are known to have stepped on mines and been killed.[65]

Conservation

Panthera pardus is listed in CITES Appendix I.[1]

The Armenian Leopard Conservation Society is a youth ecological group's working initiative, which was founded to study the leopard in Armenia and in the Caucasus region. In the present day, it has become common to establish a Leopard Record Monitoring Network in the Caucasus as a significant step in the formation of leopard distribution and ecology in the region.[32]

As of 2019[update], Nature Iraq is mapping the habitat near the border with Iran as the first stage of a conservation project.[66]

In captivity

As of December 2011, there were 112 captive Persian leopards in zoos worldwide comprising 48 male, 50 female and 5 unsexed individuals less than 12 months of age within the European Endangered Species Programme.[67]

Reintroduction projects

In 2009, a Persian Leopard Breeding and Rehabilitation Centre was created in Sochi National Park, where two male leopards from Turkmenistan are being kept since September 2009, and two females from Iran since May 2010. Their descendants are planned to be released into the wild in the Caucasus Biosphere Reserve.[68][69] In 2012, a pair of leopards was brought to the Persian Leopard Breeding and Rehabilitation Centre from Lisbon Zoo. Two cubs were born there in July 2013. It is planned to release them into the wild after they have learned survival skills.[70]

In culture

The year 2019 was announced as "The Year of the Caucasian Leopard" by the Ministry of Nature Protection of Armenia.[71]

See also

Leopard subspecies: African leopard · Arabian leopard · Anatolian leopard · Indian leopard · Indochinese leopard · Javan leopard · Sri Lankan leopard · Amur leopard · Panthera pardus spelaea

- Chinese leopard

- Zanzibar leopard

- Leopard attack

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Stein, A.B.; Athreya, V.; Gerngross, P.; Balme, G.; Henschel, P.; Karanth, U.; Miquelle, D.; Rostro, S. et al. (2016). "Panthera pardus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T15954A160698029. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/15954/160698029.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Khorozyan, I. (2014). "Morphological variation and sexual dimorphism of the common leopard (Panthera pardus) in the Middle East and their implications for species taxonomy and conservation". Mammalian Biology-Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 79 (6): 398–405. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2014.07.004.

- ↑ Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V. et al. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group". Cat News (Special Issue 11): 73–75. https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/32616/A_revised_Felidae_Taxonomy_CatNews.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y#page=73.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Farhadina, M. S.; Farahmand, H.; Gavashelishvili, A.; Kaboli, M.; Karami, M.; Khalili, B.; Montazamy, Sh. (2015). "Molecular and craniological analysis of leopard, Panthera pardus (Carnivora: Felidae) in Iran: support for a monophyletic clade in western Asia". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 114 (4): 721–736. doi:10.1111/bij.12473.

- ↑ Valenciennes, A. (1856). "Sur une nouvelles espèce de Panthère tué par M. Tchihatcheff à Ninfi, village situé à huit lieues est de Smyrne". Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences 42: 1035–1039.

- ↑ Satunin, K. A. (1914) (in Russian). Key of the Mammals of the Russian Empire. Vol. 1: Chiroptera, Insectivora and Carnivora. Tiflis: Tipografīi︠a︡ Kant︠s︡eli︠a︡rīi nami︠e︡stnika E.I.V. na Kavkazi︠e︡.

- ↑ Pocock, R. I. (1927). "Description of two subspecies of leopards". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Series 9 20 (116): 213–214. doi:10.1080/00222932708655586.

- ↑ Pocock, R. I. (1930). "The Panthers and Ounces of Asia". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 34 (1): 65–82.

- ↑ Miththapala, S.; Seidensticker, J.; O'Brien, S. J. (1996). "Phylogeographic Subspecies Recognition in Leopards (P. pardus): Molecular Genetic Variation". Conservation Biology 10 (4): 1115–1132. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10041115.x.

- ↑ Uphyrkina, O.; Johnson, E.W.; Quigley, H.; Miquelle, D.; Marker, L.; Bush, M.; O'Brien, S. J. (2001). "Phylogenetics, genome diversity and origin of modern leopard, Panthera pardus". Molecular Ecology 10 (11): 2617–2633. doi:10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01350.x. PMID 11883877. http://www.biosoil.ru/files/00001386.pdf.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Khorozyan, I. G.; Gennady, F.; Baryshnikov, G. F.; Abramov, A. V. (2006). "Taxonomic status of the leopard, Panthera pardus (Carnivora, Felidae) in the Caucasus and adjacent areas". Russian Journal of Theriology 5 (1): 41–52. https://web.archive.org/web/20160303232940/http://wild-cat.org/pardus/infos/Khorozyan2006Leopard-taxonomy.pdf.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Kiabi, B.H., Dareshouri, B.F., Ghaemi, R.A., Jahanshahi, M. (2002). "Population status of the Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor Pocock, 1927) in Iran". Zoology in the Middle East 26: 41–47. doi:10.1080/09397140.2002.10637920. http://www.kasparek-verlag.de/PDF%20Abstracts/PDF26%20Abstracts/041-048%20Kiabi-Leopard.pdf.

- ↑ Satunin, K. A. (1914). "Leopardus pardus ciscaucasicus, Satunin". Conspectus Mammalium Imperii Rossici I.. Tiflis: Tipografiâ Kancelârii Namestnika E. I. V. na Kavkaz. pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Lukarevsky, V., Malkhasyan, A., Askerov, E. (2007). "Biology and ecology of the leopard in the Caucasus". Cat News (Special Issue 2): 4–8.

- ↑ Sanei, A. (2007). Analysis of leopard (Panthera pardus) status in Iran. Tehran: Sepehr Publication Center. https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=explorer&chrome=true&srcid=0B7Vwy9iDuZifNjliMzYzNTQtZWFjYy00ODgzLWJkNWQtZmY4ZTUzOTY1MTc2&hl=en.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Lukarevsky, V.; Akkiev, M.; Askerov, E.; Agili, A.; Can, E.; Gurielidze, Z.; Kudaktin, A.; Malkhasyan, A. et al. (2007). "Status of the Leopard in the Caucasus". Cat News (Special Issue 2): 15–21. http://www.catsg.org/fileadmin/filesharing/5.Cat_News/5.3._Special_Issues/5.3.2._SI_2/Lukarevsky_et_al_2007_Status_of_the_leopard_in_the_Caucasus.pdf.

- ↑ Mallon, D.; Weinberg, P.; Kopaliani, N. (2007). "Status of the prey species of the Leopard in the Caucasus". Cat News (Special Issue 2): 22–27. http://www.catsg.org/fileadmin/filesharing/5.Cat_News/5.3._Special_Issues/5.3.2._SI_2/Mallon_et_al_2007_Status_of_prey_species_of_the_leopard_in_the_Caucasus.pdf.

- ↑ Khorozyan, I. (2008). "Panthera pardus ssp. saxicolor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008. https://www.iucnredlist.org/details/15961/0.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Khorozyan, I., Malkhasyan, A., Asmaryan, S. (2005). "The Persian leopard prowls its way to survival". Endangered Species Update 22 (2): 51–60. http://wild-cat.org/pardus/infos/Khorozyan+al2005-PersianLeopardSurvival.pdf.

- ↑ Gavashelishvili, A.; Lukarevskiy, V. (2008). "Modelling the habitat requirements of leopard Panthera pardus in west and central Asia". Journal of Applied Ecology 45 (2): 579–588. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01432.x.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 WWF (2007). Strategy for the Conservation of the Leopard in the Caucasus Ecoregion. Strategic Planning Workshop on Leopard Conservation in the Caucasus (Report). Tbilisi, Georgia, 30 May – 1 June 2007. http://assets.panda.org/downloads/caucasus_leopard_conservation_strategy_1.pdf.

- ↑ "Panthera pardus spotted in Turkey". World Bulletin. 2013. https://www.worldbulletin.net/general/panthera-pardus-spotted-in-turkey-h117601.html.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Avgan, B., Raza, H., Barzani, M., and Breitenmoser, U. (2016). "Do recent leopard Panthera pardus records from northern Iraq and south-eastern Turkey reveal an unknown population nucleus in the region?". Zoology in the Middle East 62 (2): 95–104. doi:10.1080/09397140.2016.1173904.

- ↑ Toyran, K. (2018). "Noteworthy record of Panthera pardus in Turkey (Carnivora: Felidae)". Fresenius Environmental Bulletin 27 (11): 7348–7353. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329058421.

- ↑ "Выпущенные неделю назад леопарды осваивают Кавказский заповедник". RIA Novosti. 2016. http://ria.ru/society/20160722/1472589358.html.

- ↑ "Россия и Азербайджан создадут резерват для переднеазиатского леопарда". RIA Novosti. 2016. http://ria.ru/society/20160811/1474113124.html.

- ↑ Butkhuzi, L. (2004). "Breaking news: leopard in Georgia". Caucasus Environment (2): 49–51.

- ↑ Antelava, N. (2004). Lone leopard spotted in Georgia. BBC News, 25 May 2004.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 Askerov, E.; Talibov, T.; Manvelyan, K.; Zazanashvili, N.; Malkhasyan, A.; Fatullayev, P.; Heidelberg, A. (2015). "South-Eastern Lesser Caucasus: the most important landscape for conserving the leopard (Panthera pardus) in the Caucasus region (Mammalia: Felidae)". Zoology in the Middle East 61 (2): 95–101. doi:10.1080/09397140.2015.1035003.

- ↑ Khorozyan, I. (2003). "The Persian leopard in Armenia: research and conservation". Proceedings of Regional Scientific Conference "Wildlife Research and Conservation in South Caucasus", 7–8 October 2003, Yerevan, Armenia. Yerevan. pp. 161–163.

- ↑ Khorozyan, I.; Malkhasyan, A. (2002). "Ecology of the leopard (Panthera pardus) in Khosrov Reserve, Armenia: implications for conservation". Scientific Reports of the Zoological Society "La Torbiera" (6): 1–41. http://www.wildlife.ir/Files/Leopard-Year/Khorozyan_&_Malkhasyan_2003_Ecology_in_the_leopard_in_Khosro.pdf.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Khorozyan, I. (2003). "Habitat preferences by the Persian Leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor Pocock, 1927) in Armenia". Zoology in the Middle East 30: 25–36. doi:10.1080/09397140.2003.10637984.

- ↑ Khorozyan, I.; Malkhazyan, A. G.; Abramov, A. (2008). "Presence – absence surveys of prey and their use in predicting leopard (Panthera pardus) densities: a case study from Armenia". Integrative Zoology 2008 (3): 322–332. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4877.2008.00111.x. PMID 21396082. http://www.shikahogh.am/pdf/leopardandprey.pdf. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Farhadinia, M.S.; Ahmadi, M.; Sharbafi, E.; Khosravi, S.; Alinezhad, H.; Macdonald, D.W. (2015). "Leveraging trans-boundary conservation partnerships: Persistence of Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in the Iranian Caucasus". Biological Conservation 191: 770–778. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2015.08.027. http://www.wildlife.ir/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/12/6.pdf.

- ↑ "Еще одного кавказского леопарда засняли в Армении – редчайшие кадры" (in ru). Sputnik. 2019. https://ru.armeniasputnik.am/society/20190111/16687283/Esche-odnogo-kavkazskogo-leoparda-zasnyali-v-Armenii--redchayshie-kadry.html. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ↑ Бабаева, З. (2007). "Представителю Бакинского офиса Всемирного Фонда охраны дикой природы удалось впервые сфотографировать в Азербайджане живого леопарда". Day. http://news.day.az/society/73546.html.

- ↑ Исабалаева, И. (2012). "В Гирканском национальном парке Азербайджана обнаружен еще один кавказский леопард". Novosti. https://web.archive.org/web/20121202175935/http://news.mail.ru/inworld/azerbaijan/society/11121891/.

- ↑ Maharramova, E.; Moqanaki, E.M.; Askerov, E.; Faezi, S.; Alinezhad, H.; Mousavi, M.; Zazanashvili, N. (2018). "Transboundary leopard movement between Azerbaijan and Iran in the Southern Caucasus". Cat News (67): 8–10. http://www.wildlife.ir/wp-content/uploads/sites/1/2018/06/Maharramova_et_al_2018_Transboundary_leopard_movement.pdf.

- ↑ Avgan, B.; Ismayilov, A.; Fatullayev, P.; Huseynali, T. T.; Askerov, E.; Breitenmoser, U. (2012). "First hard evidence of leopard in Nakhchivan". Cat News (57): 33.

- ↑ Breitenmoser, U.; Askerov, E.; Soofi, M.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Heidelberg, A.; Manvelyan, K.; Zazanashvili, N. (2017). "Transboundary leopard conservation in the Lesser Caucasus and the Alborz Range". Cat News (65): 24–25.

- ↑ Askerov, E.; Talibov, T.; Manvelyan, K.; Zazanashvili, N.; Fatullayev, P.; Malkhasyan, A. (2019). "Leopard (Panthera pardus) reoccupying its historic range in the South Caucasus: a first evidence (Mammalia: Felidae)". Zoology in the Middle East 65 (1): 88–90. doi:10.1080/09397140.2018.1552349.

- ↑ Sanei, A.; Mousavi, M.; Kiabi, B.H.; Masoud, M.R.; Gord Mardi, E.; Mohamadi, H.; Shakiba, M.; Baran Zehi, A. et al. (2016). "Status assessment of the Persian leopard in Iran". Cat News (Special Issue 10): 43–50.

- ↑ Sanei, A.; Zakaria, M. (2011). "Distribution pattern of the Persian leopard ("Panthera pardus saxicolor") in Iran". Asia Life Sciences (Supplement 7): 7–18. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258220250.

- ↑ Farhadinia, M.; Nezami, B.; Mahdavi, A.; Kaveh, H. (2007). "Photos of Persian Leopard in Alborz Mountains, Iran". Cat News 46: 34–35. http://wildlife.ir/Files/library/CN46_Farhadinia_et_al.pdf.

- ↑ Ghoddousi, A.; Hamidi, A. Kh.; Ghadirian, T.; Ashayeri, D.; Khorozyan, I. (2010). "The status of the Endangered Persian leopard Panthera pardus saxicolor in Bamu National Park, Iran". Oryx 44 (4): 551–557. doi:10.1017/S0030605310000827. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231840269.

- ↑ Farhadinia, M.; Mahdavi, A.; Hosseini-Zavarei, F. (2009). "Reproductive ecology of Persian leopard, Panthera pardus saxicolor, in Sarigol National Park, northeastern Iran". Zoology in the Middle East 48: 13–16. doi:10.1080/09397140.2009.10638361. http://wildlife.ir/Files/Leopard-Year/Leopard%20Sarigol%20Reproduction_2009%20ZME.PDF.

- ↑ Farhadinia, M.S.; McClintock, B.T.; Johnson, P.J.; Behnoud, P.; Hobeali, K.; Moghadas, P.; Hunter, L.T.; Macdonald, D.W. (2019). "A paradox of local abundance amidst regional rarity: the value of montane refugia for Persian leopard conservation". Scientific Reports 9 (1): 14622. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-50605-2.

- ↑ Al-Sheikhly, O. F. (2012). "The hunting of endangered mammals in Iraq". Wildlife Middle East (6): 2–3.

- ↑ Raza, H. A.; Ahmad, S. A.; Hassan, N. A.; Qadir, K. A. M.; Ali, L. (2012). "First photographic record of the Persian leopard in Kurdistan, northern Iraq". Cat News (56): 34–35.

- ↑ Kaczensky, P.; Linnell, J. D. C. (2014). Rapid assessment of the mammalian community of the Badhyz Ecosystem, Turkmenistan, October 2014. NINA Report 1148. Trondheim: Norwegian Institute for Nature Research.

- ↑ Farhadinia, M.; Memarian, I.; Hobeali, K.; Shahrdari, A.; Ekrami, B.; Kaandorp, J.; Macdonald, D.W. (2017). "GPS collars reveal transboundary movements by Persian leopards in Iran". Cat News (65): 28–30.

- ↑ Farhadinia, M.S.; Johnson, P.J.; Macdonald, D.W.; Hunter, L.T.B. (2018). "Anchoring and adjusting amidst humans: Ranging behavior of Persian leopards along the Iran-Turkmenistan borderland". PLoS ONE 13 (5): e0196602. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196602. PMID 29719005. Bibcode: 2018PLoSO..1396602F.

- ↑ "Persian Leopard Borzou Migrates to Turkmenistan". 10 October 2018. https://ifpnews.com/exclusive/persian-leopard-borzou-migrates-to-turkmenistan/.

- ↑ Habibi, K. (2004). Mammals of Afghanistan. Coimbatore: Zoo Outreach Organization.

- ↑ Moheb, Z.; Bradfield, D. (2014). "Status of the common leopard in Afghanistan". Cat News (61): 15–16.

- ↑ Manati, A. R. (2009). "The trade in Leopard and Snow Leopard skins in Afghanistan". TRAFFIC Bulletin 22 (2): 57–58.

- ↑ Hamidi, A. H. K. (2008). Persian Leopard Ecology and Conservation in Bamu National Park, Iran. Cat Project of the Month – March 2008

- ↑ Farhadinia, M.S.; Nezami, B.; Hosseini-Zavarei, F.; Valizadeh, M. (2009). "Persistence of Persian leopard in a buffer habitat in northeastern Iran". Cat News (51): 34–36. http://wildlife.ir/Files/library/persian%20leopard.pdf.

- ↑ Lukarevsky V., Malkhasyan, A., Askerov, E. (2007). "Biology and ecology of the leopard in the Caucasus". Cat News (Special Issue 2): 9–15.

- ↑ Sanei, A., Zakaria, M., Hermidas, S. (2011). "Prey composition in the Persian leopard distribution range in Iran". Asia Life Sciences Supplement 7: 19–30. http://journals.uplb.edu.ph/index.php/ALS/article/view/693/636. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ Sanei, A., Zakaria, M. (2009). Primary threats to Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Proceedings of the 8th International Annual Symposium on Sustainability Science and Management. 3–4 May 2009. Diterbitkan Oleh, Terengganu, Malaysia

- ↑ Sanei, A., Zakaria, M. (2011). "Survival of the Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in Iran: Primary threats and human-leopard conflicts". Asia Life Sciences Supplement 7: 31–39. http://journals.uplb.edu.ph/index.php/ALS/article/view/694/637. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ Sanei, A.; Mousavi, M.; Mousivand, M.; Zakaria, M. (2012). "Assessment of the Persian leopard mortality rate in Iran". Proceedings of UMT 11th International Annual Symposium on Sustainability Science and Management: 1458–1462. http://www.leopardspecialists.com/index.php/component/docman/doc_download/14-assessment-of-the-persian-leopard-mortality-rate-in-iran?Itemid=.

- ↑ Naderi, M., Farashi, A., Erdi, M.A. (2018). "Persian leopard's (Panthera pardus saxicolor) unnatural mortality factors analysis in Iran". PLoS ONE 13 (4): e0195387. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0195387. PMID 29694391. Bibcode: 2018PLoSO..1395387N.

- ↑ Schwartzstein, P. (2014). "For Leopards in Iran and Iraq, Land Mines Are a Surprising Refuge". National Geographic. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/12/141219-persian-leopard-iran-iraq-land-mine/.

- ↑ "Persian Leopard Conservation" (in en). http://www.natureiraq.org/persian-leopard-conservation.html.

- ↑ International Species Information System (2011). "ISIS Species Holdings: Panthera pardus saxicolor, December 2011". https://www.isis.org/Pages/findanimals.aspx.

- ↑ WWF (2009). "Flying Turkmen leopards to bring species back to Caucasus". WWF. http://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/news/?uNewsID=174841.

- ↑ Druzhinin, A. (2010). "Iranian leopards make themselves at home in Russia's Sochi". RIA Novosti. http://en.rian.ru/russia/20100506/158901243.html.

- ↑ WWF (2013). "First Persian leopard cubs born in Russia for 50 years". World Wide Fund for Nature International. http://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?209420/First-Persian-Leopard-cubs-born-in-Russia-for-50-years.

- ↑ "Еще одного кавказского леопарда засняли в Армении — редчайшие кадры". 2019. https://ru.armeniasputnik.am/society/20190111/16687283/Esche-odnogo-kavkazskogo-leoparda-zasnyali-v-Armenii--redchayshie-kadry.html. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

Further reading

- Sanei, A. (2016). Leopard National Conservation and Management Action Plan in Iran, Department of Environment of Iran. ISBN 978-600-04-4354-2.

- Zakaria, M. and Sanei, A. (2011). Conservation and management prospects of the Persian and Malayan leopards. Asia Life Sciences Supplement 7: 1–5.

- Sanei, A., Zakaria, M. (2008). Distribution of "Panthera pardus" in Iran in relation to its habitat and climate type. In: Saiful, A. A., Norhayati, A., Shuhaimi, M.O., Ahmad, A.K. and A.R. Zulfahmi (eds.) "Third Regional symposium on environment and natural resources". Universiti Kebangsan Malaysia, Malaysia.

- Aghili, A. (2005). Leopard Survey in Caucasus Ecoregion (Northwest) of Iran. Leopard Conservation Society, Centre for Sustainable Development (CENESTA), Iran Department of Environment, Natural Environment & Biodiversity Office

- Shakula, V. (2004). First record of leopard in Kazakhstan. Cat News |volume=41: 11–12.

- Zulfiqar, A. (2001). Leopard in Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province. Cat News |volume=35: 9–10.

- Woodroffe, R. (2000). Predators and people: using human densities to interpret declines of large carnivores. Animal Conservation (2000) 3: 165–173.

- Janashvili, A. (1984). "Leopard". Georgian Soviet Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. Tbilisi, pp. 567

- Gasparyan, K.M. and F. S. Agadjanyan. (1974). The panther in Armenia. Biological Journal of Armenia 27: 84–87.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panthera pardus saxicolor. |

- IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group: Panthera pardus in Asia and P. p. saxicolor

- Leopards .:. wild-cat.org — Information about research and conservation of leopards in Asia

- Asian Leopard Specialist Society: Research, Conservation and Management of Asian leopard subspecies

- nbcnews.com August 2007 : Zoo reveals rare Persian leopard triplets

- Iranian Cheetah Society : Leopards in Crisis in Northern Iran

- Caucasian leopard

Wikidata ☰ Q729713 entry