Biology:Photosynthetic reaction centre protein family

| Type II reaction centre protein | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

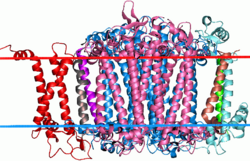

Structure of the photosynthetic reaction centre from Rhodopseudomonas viridis (PDB: 1PRC). Middle transmembrane section is the two subunits in this family; green blocks represent chlorophyll. Top section is the 4-heme (red) cytochrome c subunit (infobox below). The bottom section along with its connected TM helices is the H subunit. | |||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||

| Symbol | Photo_RC | ||||||||||

| Pfam | PF00124 | ||||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000484 | ||||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00217 | ||||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1prc / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||||

| TCDB | 3.E.2 | ||||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 2 | ||||||||||

| OPM protein | 1dxr | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Type I reaction centre protein | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Side view of Cyanobacterial photosystem I. Large near-symmetrical proteins in the center, colored blue and pink, are the two subunits of this family. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | PsaA_PsaB | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00223 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001280 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00347 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1jb0 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| TCDB | 5.B.4 | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 2 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 1jb0 | ||||||||

| Membranome | 535 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Photosynthetic reaction centre proteins are main protein components of photosynthetic reaction centres (RCs) of bacteria and plants. They are transmembrane proteins embedded in the chloroplast thylakoid or bacterial cell membrane.

Plants, algae, and cyanobacteria have one type of PRC for each of its two photosystems. Non-oxygenic bacteria, on the other hand, have an RC resembling either the Photosystem I centre (Type I) or the Photosystem II centre (Type II). In either case, PRCs have two related proteins (L/M; D1/D2; PsaA/PsaB) making up a quasi-symmetrical 5-helical core complex with pockets for pigment binding. The two types are structurally related and share a common ancestor.[1][2] Each type have different pockets for ligands to accommodate their specific reactions: while Type I RCs use iron sulfur clusters to accept electrons, Type II RCs use quinones. The centre units of Type I RCs also have six extra transmembrane helices for gathering energy.[2]

In bacteria

The Type II photosynthetic apparatus in non-oxygenic bacteria consists of light-harvesting protein-pigment complexes LH1 and LH2, which use carotenoid and bacteriochlorophyll as primary donors.[3] LH1 acts as the energy collection hub, temporarily storing it before its transfer to the photosynthetic reaction centre (RC).[4] Electrons are transferred from the primary donor via an intermediate acceptor (bacteriophaeophytin) to the primary acceptor (quinine Qa), and finally to the secondary acceptor (quinone Qb), resulting in the formation of ubiquinol QbH2. RC uses the excitation energy to shuffle electrons across the membrane, transferring them via ubiquinol to the cytochrome bc1 complex in order to establish a proton gradient across the membrane, which is used by ATP synthetase to form ATP.[5][6][7]

The core complex is anchored in the cell membrane, consisting of one unit of RC surrounded by LH1; in some species there may be additional subunits.[8] A type II RC consists of three subunits: L (light), M (medium), and H (heavy; InterPro: IPR005652). Subunits L and M provide the scaffolding for the chromophore, while subunit H contains a cytoplasmic domain.[9] In Rhodopseudomonas viridis, there is also a non-membranous tetrahaem cytochrome (4Hcyt) subunit on the periplasmic surface.

The structure for a type I system in the anaerobe Heliobacterium modesticaldum was resolved in 2017 (PDB: 5V8K). As a homodimer consisting of only one type of protein in the core complex, it is considered a closer example to what an ancestral unit before the Type I/II split is like compared to all heterodimeric systems.[2]

Oxygenic systems

The D1 (PsbA) and D2 (PsbD) photosystem II (PSII) reaction centre proteins from cyanobacteria, algae and plants only show approximately 15% sequence homology with the L and M subunits, however the conserved amino acids correspond to the binding sites of the photochemically active cofactors. As a result, the reaction centres (RCs) of purple photosynthetic bacteria and PSII display considerable structural similarity in terms of cofactor organisation.

The D1 and D2 proteins occur as a heterodimer that form the reaction core of PSII, a multisubunit protein-pigment complex containing over forty different cofactors, which are anchored in the cell membrane in cyanobacteria, and in the thylakoid membrane in algae and plants. Upon absorption of light energy, the D1/D2 heterodimer undergoes charge separation, and the electrons are transferred from the primary donor (chlorophyll a) via phaeophytin to the primary acceptor quinone Qa, then to the secondary acceptor Qb, which like the bacterial system, culminates in the production of ATP. However, PSII has an additional function over the bacterial system. At the oxidising side of PSII, a redox-active residue in the D1 protein reduces P680, the oxidised tyrosine then withdrawing electrons from a manganese cluster, which in turn withdraw electrons from water, leading to the splitting of water and the formation of molecular oxygen. PSII thus provides a source of electrons that can be used by photosystem I to produce the reducing power (NADPH) required to convert CO2 to glucose.[10][11]

Instead of assigning specialized roles to quinones, the PsaA-PsaB photosystem I centre evolved to make both quinones immobile. It also recruited the iron-sulphur PsaC subunit to further mitigate the risk of oxidative stress.[2]

In viruses

Photosynthetic reaction centre genes from PSII (PsbA, PsbD) have been discovered within marine bacteriophage.[12][13][14] Though it is widely accepted dogma that arbitrary pieces of DNA can be borne by phage between hosts (transduction), one would hardly expect to find transduced DNA within a large number of viruses. Transduction is presumed to be common in general, but for any single piece of DNA to be routinely transduced would be highly unexpected. Instead, conceptually, a gene routinely found in surveys of viral DNA would have to be a functional element of the virus itself (this does not imply that the gene would not be transferred among hosts - which the photosystem within viruses is[15] - but instead that there is a viral function for the gene, that it is not merely hitchhiking with the virus). However, free viruses lack the machinery needed to support metabolism, let alone photosynthesis. As a result, photosystem genes are not likely to be a functional component of the virus like a capsid protein or tail fibre. Instead, it is expressed within an infected host cell.[16][17] Most virus genes that are expressed in the host context are useful for hijacking the host machinery to produce viruses or for replication of the viral genome. These can include reverse transcriptases, integrases, nucleases or other enzymes. Photosystem components do not fit this mould either.

The production of an active photosystem during viral infection provides active photosynthesis to dying cells. This is not viral altruism towards the host, however. The problem with viral infections tends to be that they disable the host relatively rapidly. As protein expression is shunted from the host genome to the viral genome, the photosystem degrades relatively rapidly (due in part to the interaction with light, which is highly corrosive), cutting off the supply of nutrients to the replicating virus.[18] A solution to this problem is to add rapidly degraded photosystem genes to the virus, such that the nutrient flow is uninhibited and more viruses are produced. One would expect that this discovery will lead to other discoveries of a similar nature; that elements of the host metabolism key to viral production and easily damaged during infection are actively replaced or supported by the virus during infection. Indeed, recently, PSI gene cassettes containing whole gene suites [(psaJF, C, A, B, K, E and D) and (psaD, C, A and B)] were also reported to exist in marine cyanophages from the Pacific and Indian Oceans [19][20][21]

Subfamilies

- Photosynthetic reaction centre, M subunit InterPro: IPR005781

- Photosystem II reaction centre protein PsbA/D1 InterPro: IPR005867

- Photosystem II reaction centre protein PsbD/D2 InterPro: IPR005868

- Photosynthetic reaction centre, L subunit InterPro: IPR005871

See also

- C-terminal processing peptidase, also known as photosystem II D1 protein processing peptidase

Notes

- ↑ "Conservation of distantly related membrane proteins: photosynthetic reaction centers share a common structural core". Molecular Biology and Evolution 23 (11): 2001–7. November 2006. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl079. PMID 16887904.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Evolution of photosynthetic reaction centers: insights from the structure of the heliobacterial reaction center". Photosynthesis Research 138 (1): 11–37. October 2018. doi:10.1007/s11120-018-0503-2. PMID 29603081. Bibcode: 2018PhoRe.138...11O. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1494566.

- ↑ "Structural basis of the drastically increased initial electron transfer rate in the reaction center from a Rhodopseudomonas viridis mutant described at 2.00-A resolution". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (50): 39364–8. December 2000. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008225200. PMID 11005826.

- ↑ "The native architecture of a photosynthetic membrane". Nature 430 (7003): 1058–62. August 2004. doi:10.1038/nature02823. PMID 15329728. Bibcode: 2004Natur.430.1058B. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/102/1/huntercn1.pdf.

- ↑ "AFM studies of the supramolecular assembly of bacterial photosynthetic core-complexes". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 10 (5): 387–93. October 2006. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.08.007. PMID 16931113.

- ↑ "Coupling of light-induced electron transfer to proton uptake in photosynthesis". Nature Structural Biology 10 (8): 637–44. August 2003. doi:10.1038/nsb954. PMID 12872158.

- ↑ "Nobel lecture. The photosynthetic reaction centre from the purple bacterium Rhodopseudomonas viridis". The EMBO Journal 8 (8): 2149–70. August 1989. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08338.x. PMID 2676514.

- ↑ "Crystal structures of photosynthetic reaction center and high-potential iron-sulfur protein from Thermochromatium tepidum: thermostability and electron transfer". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (25): 13561–13566. 2000. doi:10.1073/pnas.240224997. PMID 11095707. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...9713561N.

- ↑ "Structure and function of the photosynthetic reaction center from Rhodobacter sphaeroides". J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 26 (1): 5–15. 1994. doi:10.1007/BF00763216. PMID 8027023. https://zenodo.org/record/1232456.

- ↑ "Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II from Thermosynechococcus vulcanus at 3.7-A resolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (1): 98–103. 2003. doi:10.1073/pnas.0135651100. PMID 12518057. Bibcode: 2003PNAS..100...98K.

- ↑ "The low molecular mass subunits of the photosynthetic supracomplex, photosystem II". Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1608 (2–3): 75–96. 2004. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.12.004. PMID 14871485.

- ↑ "Viral photosynthetic reaction center genes and transcripts in the marine environment". ISME J 1 (6): 492–501. 2007. doi:10.1038/ismej.2007.67. PMID 18043651. Bibcode: 2007ISMEJ...1..492S.

- ↑ "Genetic organization of the psbAD region in phages infecting marine Synechococcus strains". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (30): 11007–12. 2004. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401478101. PMID 15263091. Bibcode: 2004PNAS..10111007M.

- ↑ "Prevalence and evolution of core photosystem II genes in marine cyanobacterial viruses and their hosts". PLoS Biol. 4 (8): e234. 2006. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040234. PMID 16802857.

- ↑ "Transfer of photosynthesis genes to and from Prochlorococcus viruses". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (30): 11013–8. 2004. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401526101. PMID 15256601. Bibcode: 2004PNAS..10111013L.

- ↑ "Photosynthesis genes in marine viruses yield proteins during host infection". Nature 438 (7064): 86–9. 2005. doi:10.1038/nature04111. PMID 16222247. Bibcode: 2005Natur.438...86L.

- ↑ "Transcription of a 'photosynthetic' T4-type phage during infection of a marine cyanobacterium". Environ. Microbiol. 8 (5): 827–35. 2006. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00969.x. PMID 16623740.

- ↑ "Cyanophage infection and photoinhibition in marine cyanobacteria". Res. Microbiol. 155 (9): 720–5. 2004. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2004.06.002. PMID 15501648.

- ↑ "Photosystem-I gene cassettes are present in marine virus genomes". Nature 461 (7261): 258–262. 2009. doi:10.1038/nature08284. PMID 19710652. Bibcode: 2009Natur.461..258S.

- ↑ "Reconstructing a puzzle: existence of cyanophages containing both photosystem-I and photosystem-II gene suites inferred from oceanic metagenomic datasets". Environ. Microbiol. 13 (1): 24–32. 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02304.x. PMID 20649642.

- ↑ "Viral clones from the GOS expedition with an unusual photosystem-I gene cassette organization". ISME J 6 (8): 1617–20. 2012. doi:10.1038/ismej.2012.23. PMID 22456446. Bibcode: 2012ISMEJ...6.1617B.

References

- "X-ray structure analysis of a membrane protein complex. Electron density map at 3 A resolution and a model of the chromophores of the photosynthetic reaction center from Rhodopseudomonas viridis". Journal of Molecular Biology 180 (2): 385–98. December 1984. doi:10.1016/s0022-2836(84)80011-x. PMID 6392571.

|