Biology:Polydactyly in early tetrapods

Polydactyly in early tetrapods should here be understood as having more than five digits to the finger or foot, a condition that was the natural state of affairs in the very first tetrapods during the evolution of terrestriality. The polydactyly in these largely aquatic animals is not to be confused with polydactyly in the medical sense, i.e. it was not an anomaly in the sense it was not a congenital condition of having more than the typical number of digits for a given taxon.[1] Rather, it appears to be a result of the early evolution from a limb with a fin rather than digits.

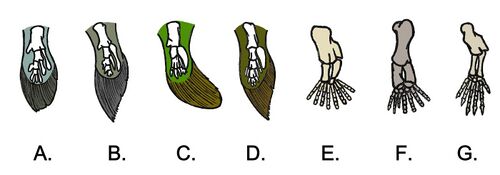

Tetrapods evolved from animals with fins such as found in lobe-finned fishes. From this condition a new pattern of limb formation evolved, where the development axis of the limb rotated to sprout secondary axes along the lower margin, giving rise to a variable number of very stout skeletal supports for a paddle-like foot.[2] The condition is thought to have arisen from the loss of the fin ray-forming proteins actinodin 1 and actinodin 2 or modification of the expression of HOXD13.[3][4]

Early groups like Acanthostega had eight digits, while the more derived Ichthyostega had seven digits, the yet-more derived Tulerpeton had six toes.[1] Crassigyrinus from the fossil-poor Romer's gap in early Carboniferous is usually thought to have had five digits to each foot. The Anthracosaurs, which may be stem-tetrapods [5][6] or reptiliomorphs,[7] retained the five-toe pattern still found in Amniotes, while further reduction had taken place on other Labyrinthodont lines, leaving the forefoot with four toes and the hind foot with five, a pattern still found in modern amphibians.[8] The increasing knowledge of Labyrinthodonts from Romer's gap has led to the challenging of the hypothesis that pentadactyly, as displayed by most modern tetrapods, is plesiomorphic. The number of digits was once thought to have been reduced in amphibians and reptiles independently,[1][9] but more recent studies suggest that a single reduction occurred, along the tetrapod stem, in the Late Devonian or Early Carboniferous.[10][11] However, even the early Ichthyostegalians like Acanthostega and Ichthyostega appear to have had the forward ossified bony toes combined in a single stout digit, making them effectively five-toed.

See also

- Polydactyl cat

- Polydactyly

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 Evolutionary developmental biology, by Brian Keith Hall, 1998, ISBN:0-412-78580-3, p. 262

- ↑ Coates, M.I. and Clack, J.A. (1990): Polydactyly in the earliest known tetrapod limbs. Nature, 347, pp.66-69.

- ↑ Zhang, J.; Wagh, P.; Guay, D.; Sanchez-Pulido, L.; Padhi, B. K.; Korzh, V.; Andrade-Navarro, M. A.; Akimenko, M. A. (2010). "Loss of fish actinotrichia proteins and the fin-to-limb transition". Nature 466 (7303): 234–237. doi:10.1038/nature09137. PMID 20574421. Bibcode: 2010Natur.466..234Z.

- ↑ Schneider, Igor; Shubin, Neil H. (December 2012). "Making Limbs from Fins". Developmental Cell 23 (6): 1121–1122. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2012.11.011. PMID 23237946.

- ↑ Laurin, M. 1998. The importance of global parsimony and historical bias in understanding tetrapod evolution. Part I. Systematics, middle ear evolution, and jaw suspension. Annales des Sciences Naturelles, Zoologie, Paris, 13e Série 19:1-42

- ↑ Marjanović, D. and M. Laurin. 2009. The origin(s) of modern amphibians: a commentary. Evolutionary Biology 36:336–338.

- ↑ Gauthier, J., A. G. Kluge, and T. Rowe. 1988. The early evolution of the Amniota; pp. 103-155 in M. J. Benton (ed.), The phylogeny and classification of the tetrapods, Volume 1: amphibians, reptiles, birds. Clarendon Press, Oxford

- ↑ Benton, M. (2005): Vertebrate Palaeontology 3rd edition. Blackwell Publishing

- ↑ Coates, M. I. 1991. New palaeontological contributions to limb ontogeny and phylogeny; pp. 325-337 in J. R. Hincliffe, J. M. Hurle, and D. Summerbell (ed.), Developmental Patterning of the Vertebrate Limb. Plenum Press in cooperation with NASO Scientific Affairs Division, New York

- ↑ Laurin, M. 1998. A reevaluation of the origin of pentadactyly. Evolution 52:1476-1482

- ↑ Ruta, M. and M. I. Coates. 2007. Dates, nodes and character conflict: addressing the lissamphibian origin problem. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 5:69-122