Biology:Pre-Columbian savannas of North America

Pre-Columbian savannas of North America, consisting of a mixed woodland-grassland ecosystem, were maintained by both natural lightning fires and by Native Americans before the significant arrival of Europeans.[1][2][3][4] Although decimated by widespread epidemic disease, Native Americans in the 16th century continued using fire to clear savanna until European colonists began colonizing the eastern seaboard. Many colonists continued the practice of burning to clear underbrush, reinforced by their similar experience in Europe, but some land reverted to forest.[1]

Postglacial events

During the Last Glacial Maximum about 18,000 years ago, the glacial front in the eastern United States extended south to the approximate location of the Missouri and Ohio River. These glaciers destroyed any vegetation in their path, and cooled the climate near their front. Pre-existing natural communities remained largely intact south of the glaciers, but saw an increase in dominance of pine and a now-extinct species of temperate spruce, (Picea critchfieldii). This area included many plant communities that rely on a lightning-based fire regime, such as the longleaf pine savanna. When the glaciers began to retreat, the ancient natural communities of the southeast would be the primary source of colonization for the newly exposed areas in the midwest.[5]

Warming and drying during the Holocene climatic optimum began about 9,000 years ago and affected the vegetation of the southeast. The prairies and savannas of the southeast expanded their range, and xeric oak and oak-hickory forest types proliferated. Cooler-climate species migrated northward and upward in elevation. This retreat caused a proportional increase in pine-dominated forests in the Appalachians.[6] At about 4,000 years BP, the Archaic Indian cultures began practising agriculture. Technology had advanced to the point that pottery was becoming common, and the small-scale felling of trees became feasible. Concurrently, the Archaic Indians began using fire in a widespread manner. Intentional burning of vegetation was taken up to mimic the effects of natural fires that tended to clear forest understories, thereby making travel easier and facilitating the growth of herbs and berry-producing plants that were important for both food and medicines.[6] In some areas, the effects of Native Americans fires would mimic natural lightning regimes, while in others they would significantly alter the natural communities.[7]

From the 16th century on, the massive depopulation of Native Americans caused by the arrival of European settlers meant an end to burning and farming across large areas.[6]

... by the time the first European observers were reporting the nature of the vegetation of the region, it is likely to have changed significantly since the regional peak of Indian influence. A myth has developed that prior to European culture the New World was a pristine wilderness. In fact, the vegetation conditions that the European settlers observed were changing rapidly because of aboriginal depopulation. As a result, canopy closure and forest tree density were increasing throughout the region.[6]

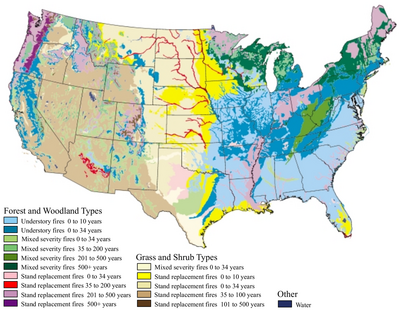

Historic or remaining savanna areas

Savanna surrounded much of the continent's central tallgrass prairie and shortgrass prairie. Fire also swept the Rocky Mountains aspen as frequently as every ten years, creating large areas of parkland.[1] In the far southwest was California oak woodland and Ponderosa Pine savanna, while further north was the Oregon White Oak savanna. The Central Hardwood Region covers a wide belt from northern Minnesota and Wisconsin, down through Iowa, Illinois, northern and central Missouri, eastern Kansas, and central Oklahoma to north-central Texas, with isolated pockets further east around the Great Lakes.[8] The Eastern savannas of the United States extended further east to the Atlantic seaboard.

In the southeast, longleaf pine dominated the savanna and open-floored forests which once covered 92,000,000 acres (370,000 km2) from Virginia to Texas. These covered 36% of the region's land and 52% of the upland areas. Of this, less than 1% of the unaltered forest still stands.[9]

In the Eastern Deciduous Forest, frequent fires kept open areas which supported herds of bison. A substantial portion of this forest was extensively burned by agricultural Native Americans. Annual burning created many large oaks and white pines with little understory.[10]

The Southeastern Pine Region, from Texas to Virginia, is characterized by longleaf, slash, loblolly, shortleaf, and sand pines. Lightning and humans burned the understory of longleaf pine every 1 to 15 years from Archaic periods until widespread fire suppression practices were adopted in the 1930s. Burning to manage wildlife habitat did continue and was a common practice by 1950. Longleaf pine dominated the coastal plains until the early 1900s, where loblolly and slash pines now dominate.[10]

At low altitudes in the Rocky Mountain region, large areas of Ponderosa pine and Douglas fir had an open park-like structure until the 1900s. In California's Sierra Nevada area, frequent fires kept clear the understory of stands of both Ponderosa pines and giant Sequoia.[10]

Destruction of the savannas

Industrialized sawmills in the early 20th century cleared many tall savanna old-growth trees, while fire suppression methods adopted in the 1930s and 1940s stopped much of the regular burning which the savanna required.[1][11][12] By the latter half of the 20th century, many researchers had rediscovered both the prehistoric use of fire and methods to practice burning, but by then almost all prairie and savanna lands had been converted to agriculture or succeeded to full-canopy forest. Modern conservation of savanna includes controlled burning, and at present about 6,000,000 acres (24,000 km2) a year are burned.[1]

See also

- Eastern savannas of the United States - Savanna in southeastern regions.

- Oak savanna - Savanna in west coast, western, and central regions.

- Native American use of fire - Other native uses of fire.

- Terra preta - Use of burning in South America agricultural use rather than grassland.

- Prairie remnant - Pre-Columbian fire dependent habitats of North America

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Brown, James K.; Smith, Jane Kapler (2000). "Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on flora". Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 2. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. pp. 40, 56–68. http://www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/pubs/4554.

- ↑ Earley, Lawrence S. (2006). Looking for Longleaf: The Fall And Rise of an American Forest. UNC Press. pp. 75–77. ISBN 0-8078-5699-1. https://archive.org/details/lookingforlongle0000earl/page/75.

- ↑ "Use of Fire by Native Americans". The Southern Forest Resource Assessment Summary Report. Southern Research Station, USDA Forest Service. http://www.srs.fs.fed.us/sustain/report/fire/fire-06.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ Williams, Gerald W. (2003-06-12). "References on the American Indian Use of Fire in Ecosystems" (PDF). http://www.blm.gov/heritage/docum/Fire/Bibliography%20-%20Indian%20Use%20of%20Fire.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Loehle, C. (2007). "Predicting Pleistocene climate from vegetation in North America". Climate of the Past 3 (1): 109–118. doi:10.5194/cp-3-109-2007. http://www.clim-past.net/3/109/2007/cp-3-109-2007.pdf.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Owen, Wayne (2002). "Chapter 2 (TERRA–2): The History of Native Plant Communities in the South". Southern Forest Resource Assessment Final Report. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station. https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/sustain/report/terra2/terra2.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ↑ David L. Lentz, ed (2000). Imperfect balance: landscape transformations in the Precolumbian Americas. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. xviii-xix. ISBN 0-231-11157-6.

- ↑ Dey, Daniel C.; Richard P. Guyette (2000). "Sustaining Oak Ecosystems in the Central Hardwood Region: Lessons from the Past--Continuing the History of Disturbance". Trans. 65th No. Amer. Wildl. and Natur. Resour. Conf. p. 170-183. http://nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/2065. Retrieved 2008-10-15.

- ↑ Hunter, William C.; Lori H. Peoples (May 2001). "Partners in Flight Bird Conservation Plan for The South Atlantic Coastal Plain (Physiographic Area 03)" (PDF). pp. 10–12, 63–64. http://www.blm.gov/wildlife/plan/pl_03_10.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 Telfer, Edmund S. (January 2000). "Regional Variation in Fire Regimes". in Jane Kapler Smith. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna.. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. pp. 9–15.

- ↑ GOBER, JIM R.. "Products of the Longleaf Pine" (PDF). Archived from the original on October 7, 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20061007170731/http://www.forestry.state.al.us/publication/TF_publications/tffall99/products_of_the_longleaf_pine.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ↑ Biswell, Harold; James Agee (1999). Prescribed Burning in California Wildlands Vegetation Management. University of California Press. pp. 86. ISBN 0-520-21945-7.