Biology:Pyrgus malvae

| Pyrgus malvae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Aston Upthorpe, Oxfordshire | |

| |

| Underside | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Hesperiidae |

| Genus: | Pyrgus |

| Species: | P. malvae

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pyrgus malvae (Linnaeus, 1758)

| |

Pyrgus malvae, the grizzled skipper, is a butterfly species from the family Hesperiidae. It is a small skipper (butterfly) with a chequered pattern on its wings that appears to be black and white. This butterfly can be found throughout Europe and is common in central and southern regions of England. The butterfly prefers three major types of habitat: woodland, grassland, and industrial.[1] Referenced as a superspecies, Pyrgus malvae includes three semispecies: malvae, malvoides, and melotis.[2] Eggs are laid on plants that will provide warmth and proper nutrition for development. As larvae, their movement is usually restricted to a single plant, on which they will build tents, unless they move onto a second host plant. Larvae then spin cocoons, usually on the last host plant they have occupied, where they remain until spring. Upon emerging as adult butterflies, grizzled skippers are quite active during the day and tend to favour blue or violet-coloured plants for food.[1][3][4] They also possess multiple methods of communication; for example, vibrations are used to communicate with ants, and chemical secretions play a role in mating.[5][6] Exhibiting territorial behaviour, males apply perching and patrolling strategies to mate with a desired female.[1]

Taxonomy/phylogeny

In terms of a species complex, Pyrgus malvae is considered a superspecies that consists of three semispecies, which exhibit geographic variations in the genitalia of both male and female butterflies. These three semispecies are considered to be the Pyrgus malvae, Pyrgus malvoides, and Pyrgus melotis types. This classification can also be described as a monophyletic clade. Significant isolation mechanisms exist to accentuate the division between the malvae type and melotis type, more than the difference between the malvae and malvoides types. In fact, interbreeding has been observed between the malvae and malvoides types, indicating their close relation - namely that they are both part of the same species.[2]

Description

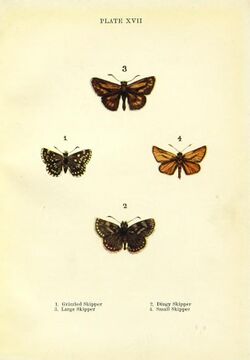

With its characteristic chequered black-and-white pattern, the grizzled skipper is quite distinctive. It is small, with an average forewing diameter of 12 millimeters, and closely resembles moths in appearance.[1] Males and females can be differentiated by the shape of their wings: males have slightly more angular wings, while females have a more rounded wing shape. Larvae are coloured green and light brown with darker brown stripes.[7] Seitz describes malvae "The terminal row of white dots developed, at least on the hindwing. Underside of hindwing reddish, with distinct white dots, those of the subterminal band being rounded. Veins bordered with yellowish white or white. In ab. taras Bergstr.(86a) the white spots of the forewing are united to form bands; occurs singly among ordinary specimens. Europe, Asia from the Mediterranean Sea to the Amur; Mongolia. — Larva yellowish grey, minutely dotted with greenish, the dots bearing short thin hairs, dorsal line darker, spiracles yellowish; in June and October on Potentilla, Dipsacus, Strawberry, Raspberry, and other plants. The butterflies are on the wing in April and May and again from the end of July onwards, on sunny slopes, roads among fields and clearings in woods, being common everywhere in Central Europe. [8]

Geographic range

Pygrus malvae can be found throughout Western Europe in northern Scandinavia, parts of Greece, and some of the Mediterranean Islands.[1] Its populations in many European countries appear to be quite stable. It is also present in Korea, as well as throughout the Mediterranean up to Middle Finland, and rarely in parts of Germany.[3]

Habitat

Although grizzled skippers occupy three major forms of habitats, they tend to settle in environments with spring nectar plants, larval food plants (agrimony, creeping cinquefoil, wild strawberry, tormentil), ranker vegetation, and edges with scrub or woodland.[1] Host plants are from the family Rosaceae with a focus on Agrimonia eupatoria as well as Potentilla.[3][9]

Woodland: This mainly consists of sparsely distributed vegetation and can have regions of bare ground that result from cutting or windblow.[1]

Grassland: These can result from three different patterns that involve animal grazing, scrub cutting, or disturbance by animals: 1) Scrubby grassland that includes bramble and wild strawberry 2) Unimproved grassland that include creeping cinquefoil 3) Unimproved grassland that includes agrimony.[1]

Industrial: Sparse vegetation with mainly wild strawberry or creeping cinquefoil depending on whether the environment is along a railway or clay working. These environments have typically been abandoned fairly recently.[1]

Other possible environments for the butterflies are heathland, shingle, sand dunes, and acidic, neutral and marshy grassland.[1]

Food resources

Adult food preference

Studies support a concentrated preference for specifically coloured flowers by grizzled skippers. They are most attracted to blue and violet while showing little or no attraction to white, yellow, or red. Butterflies have ultraviolet and blue receptors that may be responsible for Hesperiidae butterflies favoring blue. This evidence indicates that when butterflies from this species forage for food, they are particularly attentive to short-wavelength light that is reflected off flowers. In fact, this particular preference aligns with a prominent attentiveness that members of Hesperiidae have for blue. This preference may be a result of phylogenetic adaptations, foraging signals, and learning abilities. Specifically, the prevalence of blue flowers in lowlands could further intensify this preference, especially for grizzled skippers that tend to be found in lowland grasslands.[4][1]

Parental care

Host plant preference/selection

An overarching theme in behavioral ecology can be seen through female grizzled skipper investment in host plant selection. Females tend to lay eggs on host plants that are viewed as larger and more nutritionally rich. However, this nutritional advantage for caterpillars must be balanced with the presence of a warm microclimate that is suitable for the species. Warm microclimates align with P. tabernaemontani plants, but these may also have an increased chance of desiccation. On the other hand, A. eupatoria is a larger plant when near molehills and can be found in more suitable environments. As a result, A. eupatoria provides an appropriate balance for both of these requirements and is preferred as a host plant by P. malvae, particularly near molehills.[3] Females consider optical conspicuousness, or plant visibility, through prominence (height differences between host plants and vegetation). More prominent host plants, like A. eupatoria over P. tabernaemontani, are favored. However, these two different habitats are used significantly and may be evolutionary adaptations to offset the grizzled skippers’ risk of extinction imposed by a polarized weather pattern.[9]

Life history

Egg

Eggs are mainly found on agrimony, creeping cinquefoil, and wild strawberry plants, which provide nourishment for larvae.[1] Other plants that can be considered include barren strawberry, tormentil, salad burnet, bramble, dog rose, and wood avens.[1] Plants favored by mothers are typically located in bare ground or short vegetation environments, can have high nitrogen contents, and tend to be located in warmer microclimates. The eggs for grizzled skippers are laid one at a time, although females can lay them on more than two species of plants. Preferred plants have been observed to contain up to 22 eggs.[1]

Larva

This stage continues for two to three months in its entirety. At first, larvae live and spend the vast majority of their time within ‘tents’ that they build on the host leaf, and this partially feeds into their restricted mobility. The two reasons for leaving this shelter are 1.) to feed on another leaf, or 2.) to create another tent. Later on in this stage, larvae expand their mobility and are no longer restricted in diet or habitat. Plants that are higher in nitrogen content and nutrition are more highly incorporated into the diets of larger larvae, as are coarser shrubs.[1] Host plants located on molehills are favored for early larval stages due to open vegetation that is available as well as bare ground and warmer microclimates.[3]

Pupa

Pupal cocoons spun by larvae can be located on or within low vegetation. Generally, these cocoons are not found near the larvae's last tent. The location of these cocoons can consequently affect adult emergence patterns. Pupal cocoons on shorter vegetation will facilitate adult emergence earlier in the spring than pupal cocoons on longer vegetation.[1]

Adult

Grizzled skippers produce one brood per season and are in flight from the middle of March to the middle of July. Active during the day and focused on feeding or basking, they roost on tall vegetation like marjoram, knapweed, and St John's-wort.[1] In particular, adults spend days basking on bare ground and afternoons on taller vegetation. This provides them favorable microclimates and visibility.[1]

Migration

Location or regional dispersal

Butterflies move away from open spaces to the case of increasing wind speeds to seek shelter. Shelter may be particularly important because of vegetation; for example, they can support herbs and bramble. They are also useful in connecting multiple separated habitats. In fact, shelters are associated with higher activity amongst the butterflies.[10]

Enemies

Predators

Grizzled skippers belong in family Hesperiidae, but another group of butterflies (family Lycaenidae) uses the mechanism of wing expansion to produce vibrations and communicate with ants. Similar to this behavior, grizzled skippers also produce vibrations upon expanding their wings. This resembles the ‘ant-attendant’ behaviour that is specific to butterflies in the Lycaenidae. Ants are recognized as potential predators for lycaenid caterpillars, therefore, vibration signaling most likely functions as an anti-predatory survival mechanism. Similarly, grizzled skippers also exhibit this kind of vibratory communication. Although the behavior is absent during the caterpillar stage, grizzled skippers are able to produce vibrations upon wing expansion. Akin to lycaenids, grizzled skippers may use these vibrations as signals to communicate with ants and potentially as an attempt to temper aggression.[6]

Mating behaviour

Female/male interactions

Pheromones

Grizzled skippers are known to contain organs called androconia that are responsible for producing chemicals within the thorax as well as the abdomen. They are found in males at the forewing costal fold. The organs release sex pheromones that can be used as a sexual recognition mechanism and drive evolution. The process involves the male first locating a female visually, then using low concentrations of the pheromones at a relatively close proximity to indicate its viability as a mate. While courting the female, male butterflies have specialized hairlike structures called ‘tibial tufts’ on their hind legs that can be used to steer these chemicals directly to the female. However, this chemical communication cannot be differentiated between P. malvae and P. malvoides, a close relative considered a subspecies of P. malvae and not separated by isolation reproductive barriers.[5]

Courting

There are two main mating strategies that are used by grizzled skippers, which ultimately illustrate mechanisms of sexual selection by this species. In both, males demonstrate territorial behaviours. In the case of perching, males wait on taller plants for females to come to them in order to begin courting. In the case of patrolling, males locate a desired female and fly down to her.

The type of behaviour that they use in mating depends upon the pattern of food plant availability in their respective habitats.[1]

- Perching Approach: This is used in habitats that are poor for food plants. Males will engage in more of a perching approach where they await females above scrub edges that afford them with shelter, warmth, and visible range.[1]

- Patrolling Approach: This is used in habitats that are rich for food plants. Males will engage in more of a patrolling strategy by mingling with females.[1]

Climate effects on distribution

Pyrgus malvae is particularly receptive to warmer and drier climates.[11] Warmer summers are more favorable for the grizzled skipper and are positively correlated with the species. This could result from relationships between warmth and the success of the mother's ability to lay the egg as well as of larvae survival.[12] Warmer climates also tend to hasten the development of larvae and allow for earlier onset of the pupal stage.[9] Cooler northern weather may explain the concentration of this butterfly in southern regions.[12] As a result of climate warming, the grizzled skipper appears to show decreases in northern range margin, distribution area, and abundance. This response appears to be dependent upon climatic as well as nonclimatic driving forces.[13]

Physiology

Wing structure effect on flight behaviour

The wings of Pygrus malvae are only mildly adhesive, rough, and highly hydrophobic. These qualities prevent their wings from sticking to external surfaces, support their resistance to water damage, and allow the butterfly to self-clean its wings without risking desiccation. Additionally, these properties enable the grizzled skipper to avoid excess weight bearing, consequently promoting secure and efficient flight patterns.[14]

Conservation

Concerns

Past

1- Decreased woodland clearings, unimproved grassland, scrub habitats[1]

2- Unimproved grasslands and scrub habitats that have been changed[1]

3- Woodland and grassland sites that have been broken apart or deserted[1]

4- Artificial habitats that have been deteriorated[1]

Current/Future

1- Further changes that reduce open areas and spread apart clearings[1]

2- Reductions in coppice produce[1]

3- Further deteriorating unimproved grassland, scrub, and artificial habitats[1]

4- Further breaking apart and deserting habitats[1]

Prevalence decline

The grizzled skipper has notably been decreasing in its prevalence in several other European countries over the past 25 years. The species has experienced significant declines (ranging from 25% to over 50%) in United Kingdom , Croatia, Belgium, European Turkey, and the Netherlands. Less severe decline can be seen in the Czech Republic, Germany , Denmark , Finland , Luxembourg, Romania, Sweden, Slovakia, and Asian Turkey.[1] Once found across England as well as regions in Wales, the grizzled skipper is now concentrated in Central and Southern England only. In fact, five of England's counties have already experienced extinction of the species, and the butterfly can only be found in less than five sites in another five English counties. However, between 1995 and 1997, evidence of recolonization by the grizzled skipper has emerged, specifically in several counties in England.[1]

Grazing effect on population

Grazing has been applied as an approach to conservation, especially in the Netherlands where it is used to monitor the biodiversity of open habitats. Pyrgus malvae is important in these studied because it is considered as a threatened to susceptible species in the Netherlands.[15] Grazing appears to be positively associated with populations of Pyrgus malvae that are concentrated more in habitats with grazed vegetation rather than those with cut and ungrazed regions. The trend may be reflective of the fact that grizzled skippers prefer open grassland habitats. With its endangered status in the Netherlands, the grizzled skipper may benefit from extensive grazing as a nature restoration project.[15]

See also

- List of butterflies of Great Britain

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 (in en) Grizzled Skipper Action Plan (PDF Download Available). January 1998. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291312936. Retrieved 2017-09-26.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Jong, Rienk (1987). "Superspecies Pyrgus malvae (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) in the East Mediterranean, with notes on phylogenetic and biological relationships". Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie. http://repository.naturalis.nl/document/149689You.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Streitberger, Merle; Fartmann, Thomas (2013-01-01). "Molehills as important larval habitats for the grizzled skipper, Pyrgus malvae (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae), in calcareous grasslands" (in en). European Journal of Entomology 110 (4): 643–648. doi:10.14411/eje.2013.087. ISSN 1210-5759.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Kociková, Lenka; Miklisová, Dana; Čanády, Alexander; Panigaj, Ľubomír (2012). "Is colour an important factor influencing the behaviour of butterflies (Lepidoptera: Hesperioidea, Papilionoidea)?". European Journal of Entomology 109 (3): 403. doi:10.14411/eje.2012.052.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Hernández-Roldán, Juan L.; Bofill, Roger; Dapporto, Leonardo; Munguira, Miguel L.; Vila, Roger (2014-09-01). "Morphological and chemical analysis of male scent organs in the butterfly genus Pyrgus (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae)" (in en). Organisms Diversity & Evolution 14 (3): 269–278. doi:10.1007/s13127-014-0170-x. ISSN 1439-6092. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/ce81e9b8b8686755d7e0ddd1cb6f1117e3cdb1f7.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Elfferich, Nico W. (1998). "Is the larval and imaginal signalling of Lycaenidae and other Lepidoptera related to communication with ants". Deinsea 4 (1). http://natuurtijdschriften.nl/search?identifier=538588.

- ↑ Concise butterfly & moth guide. Hammond, Nicholas., Bee, Joyce., Carter, Stuart., Doyle, Sandra.. London. 2 October 2014. ISBN 9781472915832. OCLC 890699126.

- ↑ Adalbert Seitz Die Großschmetterlinge der Erde, Verlag Alfred Kernen, Stuttgart Band 1: Abt. 1, Die Großschmetterlinge des palaearktischen Faunengebietes, Die palaearktischen Tagfalter, 1909, 379 Seiten, mit 89 kolorierten Tafeln (3470 Figuren)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 Krämer, Benjamin; Kämpf, Immo; Enderle, Jan; Poniatowski, Dominik; Fartmann, Thomas (2012-12-01). "Microhabitat selection in a grassland butterfly: a trade-off between microclimate and food availability" (in en). Journal of Insect Conservation 16 (6): 857–865. doi:10.1007/s10841-012-9473-4. ISSN 1366-638X. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/73a73109e442decbe9bf9488bbff128c799f97da.

- ↑ Dover, J. W.; Sparks, T. H.; Greatorex-Davies, J. N. (1997-06-01). "The importance of shelter for butterflies in open landscapes" (in en). Journal of Insect Conservation 1 (2): 89–97. doi:10.1023/A:1018487127174. ISSN 1366-638X.

- ↑ Roy, D. B.; Rothery, P.; Moss, D.; Pollard, E.; Thomas, J. A. (2001-03-01). "Butterfly numbers and weather: predicting historical trends in abundance and the future effects of climate change" (in en). Journal of Animal Ecology 70 (2): 201–217. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2001.00480.x. ISSN 1365-2656.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 Pollard, E. (1988). "Temperature, Rainfall and Butterfly Numbers". Journal of Applied Ecology 25 (3): 819–828. doi:10.2307/2403748.

- ↑ Mair, Louise; Thomas, Chris D.; Anderson, Barbara J.; Fox, Richard; Botham, Marc; Hill, Jane K. (2012-08-01). "Temporal variation in responses of species to four decades of climate warming" (in en). Global Change Biology 18 (8): 2439–2447. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02730.x. ISSN 1365-2486. Bibcode: 2012GCBio..18.2439M. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/77486/1/Mair%20et%20al.%20main%20text.pdf.

- ↑ Sun, Gang; Fang, Yan (2015). "Anisotropic Characteristic of Insect (Lepidoptera) wing Surfaces". http://www.atlantis-press.com/php/download_paper.php?id=25838172.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 WallisDeVries, Michiel F.; Raemakers, Ivo (2001-06-01). "Does Extensive Grazing Benefit Butterflies in Coastal Dunes?" (in en). Restoration Ecology 9 (2): 179–188. doi:10.1046/j.1526-100x.2001.009002179.x. ISSN 1526-100X.

Literature

- Asher, Jim (2001). The Millennium Atlas of Butterflies in Britain and Ireland. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850565-5.

- Brereton, T. M.; Bourn, N. A. D., and Warren, M. S. (1998). Species action plan. Grizzled Skipper.

- Dover, J. W., T. H. Sparks, and J. N. Greatorex-Davies. "The importance of shelter for butterflies in open landscapes." Journal of Insect Conservation 1.2 (1997): 89–97.

- Elfferich, Nico W. "Is the larval and imaginal signalling of Lycaenidae and other Lepidoptera related to communication with ants." Deinsea 4.1 (1998): 91–96.

- Fang, Yan. "Anisotropic Characteristic of Insect (Lepidoptera) wing Surfaces." (2015).

- Hammond, Nicholas, et al. Concise Butterfly & Moth Guide. Bloomsbury, 2014.

- Hernández-Roldán, Juan L., et al. "Morphological and chemical analysis of male scent organs in the butterfly genus Pyrgus (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae)." Organisms Diversity & Evolution 14.3 (2014): 269–278.

- Jong, Rienk. Superspecies Pyrgus malvae (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) in the East Mediterranean, with notes on phylogenetic and biological relationships. Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, 1987.

- Kociková, Lenka, et al. "Is colour an important factor influencing the behaviour of butterflies (Lepidoptera: Hesperioidea, Papilionoidea)?." European Journal of Entomology 109.3 (2012): 403.

- Krämer, Benjamin, et al. "Microhabitat selection in a grassland butterfly: a trade-off between microclimate and food availability." Journal of Insect Conservation 16.6 (2012): 857–865.

- Pollard, E. "Temperature, rainfall and butterfly numbers." Journal of Applied Ecology (1988): 819–828.

- Roy, David B., et al. "Butterfly numbers and weather: predicting historical trends in abundance and the future effects of climate change." Journal of Animal Ecology 70.2 (2001): 201–217.

- Streitberger, Merle, and Thomas Fartmann. "Molehills as important larval habitats for the grizzled skipper, Pyrgus malvae (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae), in calcareous grasslands." European Journal of Entomology 110.4 (2013): 643.

- Wallisdevries, Michiel F., and Ivo Raemakers. “Does Extensive Grazing Benefit Butterflies in Coastal Dunes?” Restoration Ecology, vol. 9, no. 2, 2001, pp. 179–188., doi:10.1046/j.1526-100x.2001.009002179.x.

- Whalley, Paul (1981). The Mitchell Beazley Guide to Butterflies. London: Mitchell Beazley. ISBN 978-0-85533-348-5.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q1109803 entry

|