Biology:Serruria elongata

| Serruria elongata | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Genus: | Serruria |

| Species: | S. elongata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Serruria elongata (P.J.Bergius) R.Br.

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Serruria elongata or long-stalk spiderhead[3] is a plant belonging to the protea family. It is an erect, hairless shrublet of 1–1½ m (3½–5 ft) high with densely set, alternate, finely divided leaves lower down the plant, with needle-like segments. On top of an up to 30 cm (12 in) long inflorescence stalk are several, loosely arranged heads of pin-like, densely silvery-haired flower buds, each of which opens with four curled, magenta pink corolla lobes. The species is endemic to the southern Western Cape province of South Africa. It flowers during the southern hemisphere winter and early spring, between June and September.[4][5][6]

Description

Serruria elongata is a small, hairless shrub of 1–1½ m (3½–5 ft) high with upright or rising stems. Its leaves are arranged in what appears to be a whorl at the base of the inflorescence stalk, are 5–12½ cm (2–5 in) long twice or more feather-shaped divided in the upper half to third, with about sixty segments, hairless or young leaves sometimes felty. The highest order segments are about 1 mm (0.04 in) thick, cylinder-shaped with a blunt tip that carries a pointy extension of the midrib.[2][6]

Each stalk carries five to twenty five flower heads, arranged like a panicle or corymb on the long common inflorescence stalk, extending far above the leaves. The inflorescence stalk is hairless and 15–30 cm (6–12 in) long. The primary branches of the inflorescence stalk are up to about 6 cm (2¼ in) in length and mostly carry several heads, each of which is subtended by a lance-shaped bract of 4–8 mm (0.16–0.32 in) long, with a pointy or pointed tip (or acute or acuminate). The stalks that carry the individual flower heads are 4–6 mm (0.16–0.24 in) long, hairless, and lack or have a very small bract. Flower heads are about 1½ cm (0.6 in) across.[2][6]

The hairless bract that subtends the individual flower is purplish in colour, about 6 mm (0.24 in) long and 3 mm (0.12 in) wide, and consists of a roundish body from which a thick midrib extends in a long, stretched tip. The silvery flowers are straight while still buds. The lower part of the 4-merous perianth with the lobes fused (called the tube) is 3 mm (0.012 in) long, hairless and quickly splits to its base. The middle part where all four segments that become free as soon as the flower opens (called claws) are magenta pink, 6½–8 mm (¼–⅓ in) long, very narrowly spade-shaped, and covered in short hairs pressed to its surface. The higher part consist of four segments (called limbs) each 2 mm (0.08 in) long, narrowly oblong, with an almost pointy tip and felty hairy. These are each directly merged with a felty hairy, line-shaped anther of 1½ mm (0.06 in) long. The felty ovary is about 1 mm (0.04 in) long. It is extended into a cylinder-shaped, hairless style of about 6½ mm (¼ in) in length. It is topped by a blunt, oblong or nearly hoof-shaped stigma of about 1⅓ mm (0.05 in), that is slightly thicker than the style. The one-seeded fruit sits on a short stalk, is about 2 mm (0.08 in) long, more or less egg-shaped, with a short beak and covered in rust-coloured hairs.[2][6]

Taxonomy

The long-stalk spiderhead was first described in 1766 by the early Swedish botanist Peter Jonas Bergius, who named it Leucadendron elongatum. Carl Peter Thunberg, another Swedish naturalist who has been called "the father of South African botany", described a comparable plant and named it Protea glomerata in 1781. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck in 1791 called the plant Protea thyrsoides. In 1809, Joseph Knight published a book titled On the cultivation of the plants belonging to the natural order of Proteeae, that contained an extensive revision of the Proteaceae attributed to Richard Anthony Salisbury. Salisbury described the long-stalk spiderhead and called it Serruria crithmifolia. It is assumed that Salisbury had committed plagiarism by making use of a draft he had seen of a presentation given by Robert Brown titled On the natural order of plants called Proteaceae. Brown was to publish this talk as a paper in 1810, in which he reassigned the species, and so created the new combination Serruria elongata. The names that Salisbury had created have been therefore largely ignored by other botanists. Carl Ludwig Willdenow had named the species Protea helvola, but it took until 1856 before Carl Meissner described it, in his 1856 contribution to the series Prodromus Systematis Naturalis Regni Vegetabilis by Alphonse Pyramus de Candolle. All of these names are now considered synonymous.[2][7][8]

Distribution, habitat and ecology

The long-stalk spiderhead can be found in Du Toitskloof, between Paarl and Worcester in the northwest to the neighbourhood of Cape Agulhas in the southeast.[3] It grows at 100–650 metres (330–2,130 ft) elevation in fynbos vegetation on sandy soils that have been formed by the weathering of acid sandstones.[6]

The flowers were observed to produce a strong sweet scent, reminiscent of jasmine, late in the afternoon.[9] No smell has been noted earlier during daylight hours. The sweet scent near dusk suggests the species may be pollinated by moths.[9] The fruits are collected by ants and the seeds remain dormant until a spring that follows a summer bushfire.[6]

Conservation

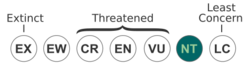

The long-stalk spiderhead is considered a near threatened species, because over the last 60 years about 30% of its habitat was lost to urban expansion, agriculture and afforestation, and competition by invasive plant species. Further population decrease is expected due to climate change. The expansion of naturalised alien ants is also a threat, since unlike native ants, they didn't carry the fruits to their underground nest before they eat the elaiosome and so fail to protect the seeds against the wildfires that naturally occur in the fynbos.[3]

References

- ↑ Rebelo, A.G.; Mtshali, H.; von Staden, L. (2020). "Serruria elongata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T113237447A185533902. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T113237447A185533902.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/113237447/185533902. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Compilation Serruria elongata". https://plants.jstor.org/compilation/serruria.elongata?searchUri=.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Long-stalk spiderhead". http://redlist.sanbi.org/species.php?species=807-39.

- ↑ "Serruria elongata". http://www.fernkloof.org.za/index.php/all-plants/plant-families/item/serruria-elongata.

- ↑ "Serruria elongata flowerheads". https://www.operationwildflower.org.za/index.php/albums/genera-m-z/serruria/serruria-elongata-flower-672.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 "Serruria elongata R.Br..". https://botany.cz/cs/serruria-elongata/.

- ↑ "Serruria elongata". https://botany.cz/cs/serruria-elongata/.

- ↑ H.O. Juel. "Plantae Thubergianae". http://bibdigital.rjb.csic.es/Imagenes/JUEL_Pl_Thunb/JUEL_Pl_Thunb_273.pdf.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 "Is Serruria elongata stalked spiderhead moth pollinated?". https://www.proteaatlas.org.za/p12see.htm.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q18083649 entry

|