Biology:Southern fin whale

| Southern fin whale[1][2] | |

|---|---|

| |

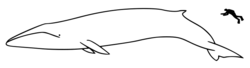

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Balaenopteridae |

| Genus: | Balaenoptera |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | B. p. quoyi

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Balaenoptera physalus quoyi (Fischer, 1829)

| |

The southern fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus quoyi) is a subspecies of fin whale that lives in the Southern Ocean.[2] At least one other subspecies of fin whale, the northern fin whale (B. p. physalus), exists in the Northern Hemisphere.[2]

Taxonomy

Based on differences in the vertebrae, the Swedish zoologist Einar Lönnberg (1931) designated Balaenoptera physalus quoyii (later the Russia n scientist A.G. Tomilin (1957) corrected this to B. p. quoyi). B. p. quoyi in turn is based on Balaena quoyi (Fischer, 1829), which was the name given to a 16.7 m (55 ft) specimen seen on the shores of the Falkland Islands by Monsieur Quoy and originally named Balaena rostrata australis by Desmoulins (1822).[3]

Size

Southern fin whales are larger than their northern hemisphere counterparts, with males averaging 20.5 m (67 ft) and females 22 m (72 ft).[4] Maximum reported figures are 25 m (82 ft) for males and 27.3 m (90 ft) for females, while the longest measured by Mackintosh and Wheeler (1929) were 22.4 metres (73 feet 6 inches) and 24.5 metres (80 feet 5 inches);[5] although Major F. A. Spencer, while whaling inspector of the factory ship Southern Princess (1936–38), confirmed the length of a 25.9 m (85 ft) female caught in the Antarctic south of the southern Indian Ocean.[6] At sexual maturity, males average 19.2 m (63 ft) and females 19.9 m (65 ft).[7]

Reproduction

Because of the opposing seasons in each hemisphere, B. p. quoyi breeds at a different time of the year than B. p. physalus. Peak conception for B. p. quoyi is June–July, while peak birthing is in May.[4] Along with the impacts of whaling, slower reproduction rate of the species may affect population recoveries as the total population size is predicted to be at less than 50% of its pre-whaling state by 2100.[8]

References

- ↑ Mead, J.G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". in Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=14300025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Balaenoptera physalus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=180527. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ Perrin, William F., James G. Mead, and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. "Review of the evidence used in the description of currently recognized cetacean subspecies". NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS (December 2009), pp. 1-35.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Evans, Peter G. H. (1987). The Natural History of Whales and Dolphins. Facts on File.

- ↑ Mackintosh, N. A.; Wheeler, J. F. G. (1929). "Southern blue and fin whales". Discovery Reports I: 259–540.

- ↑ Mackintosh, N. A. (1943). "The southern stocks of whalebone whales". Discovery Reports XXII: 199–300.

- ↑ Klinowska, M. (1991). Dolphins, Porpoises and Whales of the World: The IUCN Red Data Book. Cambridge, U.K.: IUCN.

- ↑ CSIRO. 2017. Post-whaling recovery of Southern Hemisphere. Phys.org. Retrieved on August 22, 2017

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q7570671 entry

|