Biology:Spotted sunfish

| Spotted sunfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Family: | Centrarchidae |

| Genus: | Lepomis |

| Species: | L. punctatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lepomis punctatus (Valenciennes, 1831)

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Bryttus punctatus Valenciennes, 1831 | |

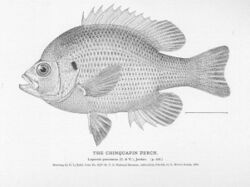

The spotted sunfish (Lepomis punctatus), also known as a stumpknocker,[3] is a member of the freshwater sunfish family Centrarchidae and order perciformes. The redspotted sunfish, redear sunfish and pumpkinseed sunfish are its closest relatives.[4] Lepomis punctatus is olive-green to brown in color with black to reddish spots at the base of each scale that form rows of dots on the side. The scientific name punctatus refers to this spotted pattern.[5] It was first described in 1831 by Valenciennes.

The spotted sunfish is a warmwater native of the Southeastern United States that inhabits areas of slow moving water. It is a benthic insectivore. Spotted sunfish do not commonly exceed 10 cm and a weight of 3 oz. It has some value as a pan fish and is occasionally caught by bream anglers. Spotted sunfish exhibit similar breeding behavior to other sunfishes. A single male guards a nest with multiple females.[4] It is evaluated by the IUCN as a Least concern species and shows little danger of decline or high sensitivity to habitat changes.[6] It has been suggested that it could be used as an indicator species, making it valuable to stream management. The spotted sunfish is a habitat generalist, but prefers complex habitats.[7] It has not been established as an invasive species in other parts of the world.

Originally Lepomis punctatus and Lepomis miniatus were both classified as the same species Lepomis punctatus. Morphological differences and molecular evidence supported a significant difference in the eastern and western species of Lepomis punctatus. The species was divided into subspecies Lepomis punctatus punctatus in the east and Lepomis punctatus miniatus in the west. Later (1992) miniatus was elevated into its own species.[8][9]

Geographic distribution

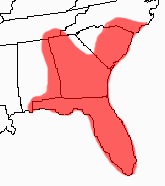

The spotted sunfish is a subtropical fish of the Southeastern United States found at latitudes of 41°N - 26°N. It is found in the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal drainages from the Cape Fear region in North Carolina to the Apalachicola River system in western Florida. The northernmost extent of its range is southern Tennessee. It is a warmwater fish and most abundant below the Fall Line.[4][10] In Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia the spotted sunfish has not faced decline, but is vulnerable to decline in North Carolina. Its vulnerability has not been evaluated in South Carolina or Florida, but there is not evidence that it is threatened there. This range is fairly common to other Lepomis, though others have ranges farther northward or westward.[11] No populations have been recorded outside of the native range.[7] In older literature the range of the spotted sunfish may include that of the redspotted sunfish, which occurs farther westward into Texas and northward up the Mississippi river.[4]

Ecology

Spotted sunfish are largely insectivores throughout their entire lives, feeding on midge larvae and other immature insects. Most prey is benthic in origin, but insects at the surface are also preyed upon. Bream anglers have caught spotted sunfish using crickets or worms. They are also known to feed on microcrustaceans such as amphipods (Hyalella) and cladocerans.[4][11] Spotted sunfish capture individual prey by suction feeding. Competition among various centrarchids is limited by physical difference in jaw mechanisms. For example, spotted sunfish and bluegill feed on similar prey items. Design of the lower jaw and therefore speed of capture varies between these two fishes; what one can easily capture the other cannot.[12]

Because sunfish feed on similar prey items throughout their lives, competition occurs between young and adult fish. Centrarchids in general are top predators in many habitats, and a sunfish's main competitor may be other sunfish. Benthic organisms such as crayfish and other fish feed on eggs. In the closely related bluegill, cannibalism in areas of high nest density has been observed. This suggests that spotted sunfish could also be cannibalistic in similar situations. High densities of hydra were also linked to high mortality. Piscivores such as largemouth bass are predators of sunfish.[13]

The spotted sunfish is a general habitat selector, but exhibits certain preferences. Juvenile and adults choose similar habitats, though younger fish sometimes show a preference for greater vegetation.[7] It is a demersal fish that inhabits slow moving streams and rivers, swamps, and less brackish portions of estuaries.[4] Spotted sunfish prefer heavily vegetated lake bottoms.[5] Limestone, sand and gravel are preferred substrates.[10] The Southeastern United States has acidic rain with a pH of 4.7-4.9. There is also a low carbonate hardness of Southeastern waters. This makes the area sensitive to acidification. Aquarists keeping sunfish have reported that they do best in neutral to high pH waters, in some extreme cases pH as high as 9.0 is observed. Acidification of their habitat could have negative impacts on the spotted sunfish.[citation needed]

Spotted sunfish typically reach a length of 9.8 cm (3.86 in), with a record of 20 cm (7.87 in).[10] A maximum weight of about three ounces is common.[14]

Life cycle

Spawning occurs from May to August in shallow water near ample cover. Males may construct either singular or colonial nests, though some have suggested that spotted sunfish are less colonial than other Lepomis. There may be several females to a single male. A female may have to attempt to enter a nest multiple times before she is accepted. Eggs are blueish in color. The male guards the eggs until they hatch and the fry disperse. Young grow about 3.3 cm in the first year.[4] Like other centrarchid fishes, Lepomis punctatus reaches sexual maturity after about two years. The average brood size is approximately 15,000. Spotted sunfish are not expected to live longer than five years.[15] Spotted sunfish have been known to hybridize with bluegill.[4]

Like many fish, males of Lepomis punctatus may exhibit one of two different breeding behaviors. A bourgeois male builds nests, attracts females, and guards the eggs. Parasitic cuckolder males (sometimes called satellite males) attempt to steal fertilizations from the guardian male and leave him to guard the nest. Spotted sunfish cuckolders are visibly different from other males. They are smaller and less conspicuous, and often like a female or juvenile.[16] Parasitic males may also display female mimicry, whereby the male mimics the behavior of a female to gain acceptance into a nest. This is thought to be common in centrarchid fishes relative to other fish. This behavior may help the guardian male by making his nest seem more attractive to females. Sunfish females prefer nests that are already populated by other females.[17]

Bourgeois males as sires were shown to be far more common than parasitic males in a study by Dewoody, et al. Although nearly half of the nests showed evidence for parasitism, 98% of the embryos were sired by a single guardian male. When nest density is high a guardian male may fertilize nearby nests when the opportunity arises. Most nests in this study, 87%, contained eggs from at least three females, and most nests had five or more females.[16]

Management

The spotted sunfish is not a threatened species, and has not been evaluated by the IUCN. No current management practices exist for this species by itself, however general habitat improvements benefit the species. Its potential as an indicator species makes it valuable to stream management.[6] It faces potential vulnerability in North Carolina, but has not faced significant decline or need for immediate management.[11] Because it is common, the spotted sunfish has been used in many studies of centrarchid fishes. It is not a common fish in aquariums. It has little commercial or sport value, except as a potential pan fish. It is feisty and has firm flesh.[4] General centrarchid management should be sufficient to maintain a healthy population of spotted sunfish. Intense management for more desirable sport fish could cause a decline in spotted sunfish. Conflicts between invasive cichlids and centrarchids has been observed.[18] Management to prevent the spread of cichlids is an important step in maintaining the sunfish population. As with many exotic fish, the cichlids originated from aquarium releases or escapes. Hurricanes and floods have aided the spread of exotic species.[19] One current management practice is to ban the sale of an animal in an area where it could be established. Further study of this fish may reveal areas where it faces decline. Drainage of wetlands and channelization would be expected to reduce abundance.[citation needed]

The spotted sunfish has been shown to have potential as an indicator species. Spotted sunfish select habitats with high complexity and depth. They are frequently found in areas with woody debris that offer shelter from velocity and provides cover. Small decreases (0.30m) in river stage below base flow conditions resulted in 20-70% declines in a study by Dutterer and Allen. Though the spotted sunfish itself is not threatened, managing for this fish benefits the entire aquatic community.[7] Similar centrarchids are preferred by anglers; the spotted sunfish must be closely watched to ensure that habitat is not modified for bluegill or redbreast sunfish at the expense of the spotted sunfish.[citation needed]

A threat to many centrarchids and potentially the spotted sunfish are invasive cichlids from the pet trade. The invasive Rio Grande cichlid (Herichthys cyanoguttatus) has had negative effects on bluegill in New Orleans. The cichlid was aggressive towards the bluegill and took over some nesting sites.[18] Several species of cichlid have become established in the Southeastern United States, particularly in the Everglades.[20] These species include the firemouth cichlid, convict cichlid, Mayan cichlid, and Salvin's cichlid. As with any invasive species, these should be monitored and removed if possible or practical.[citation needed]

There is potential that the range of invasive cichlids will increase as climate continues to warm .[21] Conflicts between these invasive species and the spotted sunfish should be closely monitored. This would not only benefit the spotted sunfish, it could provide valuable information for all centrarchids.[citation needed]

References

- ↑ NatureServe (2013). "Lepomis punctatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: e.T202560A18229920. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T202560A18229920.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/202560/18229920. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2019). "Lepomis punctatus" in FishBase. December 2019 version.

- ↑ "Stumpknocker". Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stumpknocker.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 "Newfound Press: The Fishes of Tennessee, By David A. Etnier and Wayne C. Starnes". Newfoundpress.utk.edu. 2012-04-09. http://www.newfoundpress.utk.edu/pubs/fishes/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Freshwater Fish - Spotted Sunfish". Myfwc.com. http://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/profiles/fish/freshwater/spotted-sunfish/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Search for Lepomis punctatus : Spotted Sunfish (Least Concern)". Iucnredlist.org. http://www.iucnredlist.org/search.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Andrew C. Dutterer; Michael S. Allen (February 2008). "Spotted Sunfish Habitat Selection at three Florida Rivers and Implications for Minimum Flows". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 137 (2): 454–466. doi:10.1577/T07-039.1.

- ↑ Bermingham, E.A. (1986). "Molecular Zoogeography of Freshwater Fishes in the Southeastern United States". Genetics 113 (4): 939–65. PMID 17246340.

- ↑ Warren, M.L. Variation of the spotted sunfish, Lepomis punctatus complex (Centrarchidae): morphometrics, pigmentation and species limits. Bulletin- Alabama Museum of Natural History. (2008)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Lepomis punctatus, Spotted sunfish". Fishbase.org. 2012-07-03. http://www.fishbase.org/summary/Lepomis-punctatus.html.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "NatureServe Explorer : Lepomis punctatus (Valenciennes, 1831) : Spotted Sunfish". Tnfish.org. http://www.tnfish.org/SpeciesFishInformation_TWRA/Research/SpottedSunfish_LepomisPunctatusInformation_NS.pdf.

- ↑ Wainwright, P.C.; Shaw, S. (1999). "Morphological basis of kinematic diversity in feeding sunfishes". Experimental Biology 202 (22): 3101–10.

- ↑ Cooke, S.P. (2009). Centrarchid Fishes: Diversity, Biology and Conservation. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 118–119. ISBN 9781444316049. https://books.google.com/books?id=mNqnLG5ssy8C&pg=PA142. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ "Spotted Sunfish - Lepomis punctatus". Hrla.com. http://www.hrla.com/NCFish/spotted_sunfish.htm.

- ↑ "Lepomis punctatus (Spotted sunfish)". Global Species. 2010-02-01. http://www.globalspecies.org/ntaxa/661065.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Dewoody, J.A.; Fletcher, D.E.; Mackiewicz, M.; Wilkins, S. D.; Avise, J.C. (2000). "The Genetic Mating System of Spotted Sunfish (Lepomis punctatus): Mate Numbers and the Influence of Male Reproductive Parasites.". Molecular Ecology: 2119–2129. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01123.x. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/12204476. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ Dominey, Wallace J. (1981-02-01). "Maintenance of female mimicry as a reproductive strategy in bluegill sunfish (Lepomis macrochirus)". Environmental Biology of Fishes 6: 59–64. doi:10.1007/BF00001800.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Lorenz, T.O.; O'Connell, M.T.; Schofield, P.J. (2011). "Aggressive interactions between the invasive Rio Grande cichlid (Herichthys cyanoguttatus) and native bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus), with notes on redspotted sunfish (Lepomis miniatus)". Journal of Ethology 29: 1. doi:10.1007/s10164-010-0219-z.

- ↑ Baier, Robert E. "BestThinking / Trending Topics / Science / Biology & Nature / Natural Resources / Floods Spread Invasive Species". Bestthinking.com. http://www.bestthinking.com/trendingtopics/science/biology_and_nature/natural_resources/floods-spread-invasive-species.

- ↑ [1][|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Rahel, Frank J.; Olden, Julian D. (2008). "Assessing the Effects of Climate Change on Aquatic Invasive Species". Conservation Biology 22 (3): 521–533. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00950.x. PMID 18577081.

Wikidata ☰ Q1069776 entry

|