Biology:Ticks of domestic animals

Ticks of domestic animals directly cause poor health and loss of production to their hosts. Ticks also transmit numerous kinds of viruses, bacteria, and protozoa between domestic animals.[1] These microbes cause diseases which can be severely debilitating or fatal to domestic animals, and may also affect humans. Ticks are especially important to domestic animals in tropical and subtropical countries, where the warm climate enables many species to flourish. Also, the large populations of wild animals in warm countries provide a reservoir of ticks and infective microbes that spread to domestic animals. Farmers of livestock animals use many methods to control ticks, and related treatments are used to reduce infestation of companion animals.

Variety of ticks affecting domestic animals

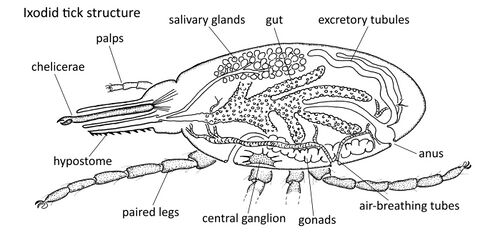

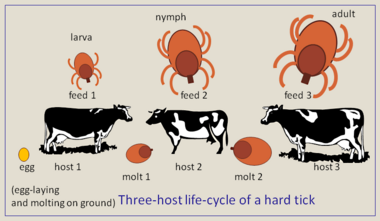

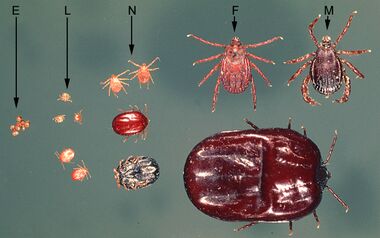

Ticks are invertebrate animals in the phylum Arthropoda, and are related to spiders. Ticks are in the subclass Acari, which consists of many orders of mites and one tick order, the Ixodida. Some mites are parasitic, but all ticks are parasitic feeders. Ticks pierce the skin of their hosts with specialized mouthparts to suck blood, and they survive exclusively by this obligate method of feeding. Some species of mites may be mistaken for larval ticks at infestations on animal hosts, but their feeding mechanisms are distinctive. All ticks have an incomplete metamorphosis: after hatching from the egg, a series of similar stages (instars) develops from a six-legged larva, to eight-legged nymph, and then a sexually developed, eight-legged adult. Between each stage is a molt (ecdysis), which enables the developing tick to expand within a new external skeleton. Ticks are grouped in three families, of which two have genera of importance to domestic animals, as follows.[2] The family Argasidae contains the important genera Argas, Ornithodoros, and Otobius. These genera are known as soft ticks because their outer body surfaces lack hard plates. The family Ixodidae contains 14 genera,[3] including Amblyomma, Dermacentor, Haemaphysalis, Hyalomma, Ixodes, Margaropus, and Rhipicephalus. Also, the important boophilid ticks, formerly of the genus Boophilus, are now classified as a subgenus within the genus Rhipicephalus.[4][5] These genera are known as hard ticks because their outer surfaces have hard plates. Within these genera are, very roughly, 100 species of importance to domestic animals.[6] Some of these species are also important to humans. The only countries that do not have some kind of problem with ticks on domestic animals are those that are permanently cold. An outline classification of the Acari, including the two families of ticks of importance to domestic animals is in the article Mites of livestock.

Typical ticks of domestic animals

Amblyomma and Rhipicephalus ixodid ticks

Amblyomma species are widespread on domestic animals throughout tropical and subtropical regions. Typical Amblyomma species are: Amblyomma americanum, the lone star tick of the Southern and Eastern USA; Am. cajennense, the Cayenne tick of South America and Southern USA; Amblyomma variegatum, the bont tick of Africa and the Caribbean (see Gallery below for photograph of female and male). A typical Rhipicephalus species is Rhipicephalus sanguineus, the tropical dog tick, specialized to feed only on dogs. It is distributed globally throughout the warm countries, wherever humans with their dogs live. Typical Rhipicephalus species that feed on cattle in Africa are R. appendiculatus, the brown ear-tick, and R. evertsi, the red-legged tick. Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus (or now simply Rhipicephalus microplus) is the most important tick of cattle in many tropical and subtropical countries to which it spread from Southeast Asia on transported cattle.

Boophilid ticks, a subgenus within Rhipicephalus

These ticks, commonly known as cattle ticks or blue ticks, have a highly characteristic morphology and one-host lifecycle. They have high specificity for cattle as hosts and their morphological characteristics used for identification are less distinct than those of three-host rhipicephalids such as R. appendiculatus. They are economically important to the cattle-rearing industry by causing direct parasitic losses and by transmission of microbes. In addition to Rhipicephalus microplus, species of most importance to domestic animals are R. annulatus, which is widespread in tropical and subtropical countries, and R. decoloratus which occurs in Africa.[citation needed]

One-host lifecycle of R. microplus

These ticks are adapted to the advantages of specialising to feed on cattle and with all the feeding stages occurring on one individual host in a rapid sequence. They also can survive by feeding on deer or some wild bovid hosts. Infestation starts when larvae on vegetation attach to a new host. When a larva feeds, it molts at the site where it feeds and emerges as a nymph. The nymph feeds at the same site or close by and molts where it feeds. It emerges from molt as either an adult female or male. The female's single large blood meal is converted into a batch of 2000 eggs. The males take several small meals of blood to support their repeated attempts at mating. The molts are rapid and the next stage remains in the hair coat to start feeding again. The combined feeding and molting periods take about 21 days. The engorged female drops from the host, hides under leaf litter on soil surface, lays one batch of eggs, and then dies. When eggs hatch, the larvae crawl up grass stems and wait until they can attach to passing cattle.[citation needed]

Hyalomma ticks

This genus contains many species of hard ticks important to domestic animals in hot, dry regions in Africa, the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, Pakistan, India,[7] and through to China. Typical species are Hyalomma anatolicum, Hy. rufipes, Hy. truncatum, and Hy. detritum, which feed as adults on cattle, sheep, and goats. Hyalomma dromedarii is specialized to feed on dromedary camels. Hyalomma ticks are adapted to live in regions with large seasonal variation of temperature and low rainfall. Diapause is an important mechanism to adjust to these climates. Another adaptation is to have a lifecycle within one species that can be two-host or three-host. For example: Hy. anatolicum may feed on a hare, molt on the hare, and feed again on the same individual hare, detach and molt to an adult and then feed on a cow - that is a two-host lifecycle. Or it may feed as a larva on a gerbil, then as a nymph on a cow, and then as an adult on another cow in a three-host lifecycle. Furthermore, this tick commonly feeds as a three-host tick with larvae, nymphs, and adults feeding on separate individual dairy cows confined to cattle housing in zero-grazing systems.[citation needed]

Argas and Ornithodoros soft ticks

Argas persicus, the fowl tick, is a major pest of poultry birds. The tampan ticks within the Ornithodoros moubata complex of species infest domestic pigs and also feed on humans. Ornithodoros savignyi is often found in large numbers at enclosures where camels and cattle are herded. Many species of argasid soft ticks are adapted to live in the nest or regular resting sites of their hosts, often waiting for months or even years for the host to return and enable the tick to feed. This nest-dwelling behavior is described as endophilic or nidicolous.[citation needed]

Multihost lifecycle of O. moubata

Argasidae soft ticks have different lifecycles from Ixodidae hard ticks, and these are very variable between species.[1] Typically, in Ornithodoros, a larva hatches from an egg laid in the nest or resting place of the host. The larva does not feed, but directly molts into the first nymph stage. This stage feeds, then molts into the next nymph stage. Feeding by soft ticks is generally completed within minutes rather than days, as with hard ticks. Depending on circumstances, four or five nymph stages occur, each progressively larger. Finally, a molt produces an adult female or male. The female takes repeated blood meals that are small compared to a female hard tick. Each blood meal is converted to a small batch of eggs. The male feeds sufficiently to support its mating. The lifecycle of Argas persicus is similar, but the larva feeds on blood of its bird host, remaining attached around 7 days.[citation needed]

Other groups of ticks

Other genera with species that are often of high local importance to domestic animals include the following examples, some of which are illustrated in the gallery below. Ixodes (Ixodes ricinus, the deer tick of Europe; Ixodes scapularis, the black-legged tick of North America; Ixodes holocyclus, the paralysis tick of Australia). Haemaphysalis (Ha. leachii, the yellow dog tick of the tropics). Dermacentor (Dermacentor andersoni, the Rocky Mountain wood tick; Dermacentor variabilis, the American dog tick; D. reticulatus, the ornate dog tick of Europe). D. nitens, the tropical horse tick of the Americas, has a one-host lifecycle similar to the boophilids. Margaropus winthemi, the beady-legged tick, infests horses and cattle in South Africa. The soft tick Otobius megnini, the spinose ear tick, has its nymphs feeding within the ear canal of many species of domestic animals. Adults of Ot. megnini do not feed. This tick occurs in the Americas and has spread to Africa and Asia.[citation needed]

Negative impacts to health

Biting stress and lost production

When a hard tick pierces the skin of its host, initially little or no pain is caused. Later, during the prolonged feeding of ticks, inflammation is caused at the wound, followed by acquired immune reactions in the skin (dermal hypersensitivities types 1 and 4) to the foreign proteins in tick saliva. This defense by the host is generally effective, but at the cost of pruritus (itch) and pain at the feeding site. Infestations of ticks on certain individual animals of a herd of livestock animals can build up to very high levels. This occurs on a minor proportion of individuals in the herd, whilst most individual animals have low infestations. On a herd basis, the accumulated effect of this biting stress can cause loss of appetite and loss of blood. These two losses result in reduced feed intake and anemia; combined, they cause a lower rate of growth or of milk production compared to hosts without tick infestation.[8][9] The feeding of soft ticks can cause severe biting stress because of the pain whilst they feed; Ornithodoros savignyi feeding on livestock that are herded in enclosures during nighttime is one notorious example.

Physical damage

At each feeding site of hard ticks, granuloma and wound healing produce a scar that remains for years after the tick has detached. When the skin of livestock animals is made into leather, these scars remain as blemishes that reduce the value of the leather. Larger ticks cause obstructive and painful damage, such as Amblyomma variegatum adults, which often feed on udders of cattle and reduce suckling by the calves. Hyalomma truncatum adults feed on the feet of sheep and goats, causing lameness. Wounds caused by dense clusters of adult ticks can make the host susceptible to infestation with larvae of flesh-eating myiasis flies, such as the screw-worm, Cochliomyia hominivorax.[10][11]

Poisoning

When ticks feed, they secrete saliva containing powerful enzymes and substances with strong pharmacological properties to maintain flow of blood and reduce host immunity. Sometimes, this causes a poisoning of the host. This is not because of a functional toxin in the sense that snake poison is functional for the snake. However, the result can be various forms of toxaemia caused by a variety of ticks. A moist eczema, sometimes with hair loss (alopecia) known as sweating sickness in cattle is caused by Hyalomma truncatum. Tick paralysis can be life-threatening and is caused in sheep by feeding of Ixodes rubicundus of South Africa. In cattle, paralysis is caused by both Dermacentor andersoni in North America and the Australian paralysis tick, Ixodes holocyclus. I. holocyclus also causes paralysis in dogs and humans.[12][13][14]

Ticks as vectors of disease

Because ticks feed repeatedly and only on blood, and have long lives, they are suitable hosts for many types of microbes, which exploit the ticks for transmission between one domestic animal and another. Ticks are thus known as vectors (transmitters) of microbes. Most of these parasitic relationships are highly developed with a strict biological relationship between the microbe and the tick's gut and salivary glands. However, some microbes, such as Anaplasma marginale and A. centrale, can also be transmitted by biting flies, or by blood on injection needles (iatrogenic transmission). A characteristic of diseases caused by tick-transmitted microbes is that herds or flocks of livestock often acquire effective levels of immune resistance to both the vector ticks and the microbes, so outbreaks of acute disease tend to be rare. This stability is often due to immunity to the microbes developing as a result of survival through early infection from ticks carrying small infective doses of the microbe, the epidemiology of infections with Babesia species of protozoa is a well described example.[15] The ticks are often constantly present and long-lived. Acquisition of immunity may be aided by the protection of antibodies in the mother's colostrum (first milk).

At least one microbe causing disease associated with ticks is not transmitted by the ticks. The skin disease dermatophilosis of cattle, sheep, and goats is caused by the bacterium Dermatophilus congolensis, which is transmitted by simple contagion. When Amblyomma variegatum adult ticks are also feeding and causing a systemic suppression of immunity in the host, then dermatophilosis becomes severe or even fatal.[16]

Viral diseases

The virus of Nairobi sheep disease in East Africa is transmitted by Rhipicephalus ticks. African swine fever is naturally transmitted between wild species of the pig family by feeding of Ornithodoros moubata group ticks. This pattern of transmission can expand to include domestic pigs. However, within groups of domestic pigs, the virus can also be transmitted by contagion. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus is transmitted between many mammal species by Hyalomma truncatum, Hyalomma rufipes, and Hyalomma turanicum over a wide area of Africa, Europe, and Asia. In cattle and sheep, it causes mild fever and its main importance is when it spreads to humans (zoonosis) by feeding of the larvae or nymphs of these ticks.[17] There are other viruses transmitted by ticks between wild animals and that have zoonotic importance when humans also become infected. The epidemiological pathways of these viruses can also involve domestic animals, if only by being hosts that add to the size of the tick population. Examples include the viruses that cause Tick-borne encephalitis, and Kyasanur Forest disease.[18]

Bacterial diseases

Borrelia bacteria are well described elsewhere in association with Ixodes ticks for causing Lyme disease in humans, but this disease also affects domestic dogs. Borrelia anserina is transmitted by Argas persicus to poultry, causing avian borreliosis in a wide spread of tropical and subtropical countries.[19] Anaplasma phagocytophilum (formerly Ehrlichia phagocytophila) is a bacterium of deer that spreads to sheep where it causes tick-borne fever in Europe, resulting in abortion by ewes and temporary sterility of rams. This bacterium invades and proliferates in neutrophil cells of the blood. This depletes these antibacterial cells and renders the host susceptible to opportunistic infections by Staphylococcus aureus bacteria which invade joints and cause the crippling disease of sheep called tick pyaemia. Anaplasma marginale infects marginal areas of red blood cells of cattle and causes anaplasmosis wherever boophilid ticks occur as transmitters. Anaplasma centrale tends to infect the central region of red blood cells, and is sufficiently closely related to An. marginale to have been used from long ago as a live vaccine to protect cattle against the more virulent An. marginale. Sheep and goats suffer disease from infection with Anaplasma ovis which is transmitted similarly to the anaplasmas described above. Ehrlichia ruminantium (formerly Cowdria ruminantium) is transmitted mainly by Amblyomma hebraeum and Am. variegatum in Africa, causing the severe disease heartwater in cattle, sheep, and goats. This disease is named after the prominent sign of pericardial edema. The bacteria infect the brain, causing prostration. Heartwater also occurs on the Caribbean islands, having spread there on shipments of cattle from Africa about 150 years ago, before anything was known of tick transmitted microbes.[11][20]

Protozoal diseases

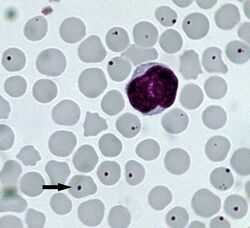

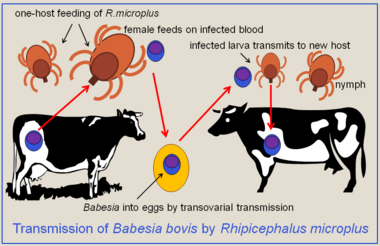

Babesia bovis protozoa are transmitted by R. microplus and cause babesiosis or redwater fever in cattle throughout the tropics and subtropics wherever this boophilid species occurs. The less pathogenic Ba. bigemina is transmitted by R. microplus and R. decoloratorus. Development of Babesia in the tick is complex and includes sexual reproduction. These Babesia are transmitted from adult female boophilid ticks to the next generation, as larvae, by infection of the eggs. This is known as transovarian transmission; it provides the only opportunity for transmission through one-host ticks. Other species of Babesia are transmitted by three-host ticks in ways similar to Theileria protozoa, as described below. In cattle, infection of the red blood cells may grow rapidly to create a potentially fatal inflammatory crisis of the blood. The name redwater (coloured urine) derives from the hemoglobinuria caused by the destruction of red blood cells infected with the merozoite stage of Babesia; anemia results from the same destruction. Horses suffer babesiosis or biliary fever when infected by Ba. equi or B. caballi. This occurs in many countries where vector ticks are found, such as R. e. evertsi, Hy. truncatum, and D. nitens. Dogs are at risk from severe infection with Ba. canis and its subspecies, transmitted by the dog ticks R. sanguineus, D. reticulatus, and Ha. leachi. Domestic cats become infected with Ba. felis and Ba. cati from feeding ticks. Cytauxzoon felis is a protozoan related to Babesia and Theileria. It is transmitted by the American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis. This microbe circulates between wild bobcats in southern USA, causing little apparent disease. If it infects domestic cats, it causes a cytauxzoonosis that is eventually fatal.[citation needed]

Theileria annulata is a protozoan closely related to Babesia. In cattle, it causes the disease tropical theileriosis throughout a long arc of countries from Morocco across to China.[21] Theileria parva is the causative microbe of East Coast fever of cattle in Eastern, Central, and Southern Africa. Theileria species infect monocytic white blood cells of their hosts. The infected cells are induced to divide by the Theileria, which then proliferates within each daughter cell, in a rapidly expanding infection. This causes multiple inflammatory crises, of which pulmonary edema is a predominant cause of death. Theileria annulata is transmitted by Hy. anatolicum, Hy. detritum, and other hyalommas. Theileria parva is transmitted predominantly by Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. Because this is a three-host feeding tick, the opportunities for transmission are from infected cow to feeding larva then through the molt into the nymph which feeds and transmits. Similarly, transmission can also be from feeding nymphs to infected adult. This is known as transstadial transmission, and no transovarian transmission occurs in this case. The development of Theileria in ticks includes sexual reproduction which enables generation of new variants that can evade the immune mechanisms of cattle.[22]

Disease control methods

Treatment with chemical and botanical pesticides against ticks

Synthetic chemical acaricides

Ticks infesting sheep and cattle have been controlled with a wide variety of chemicals ranging from coal tar extracts, arsenic salts, and specific pesticidal chemicals such as DDT for many decades. These are now replaced by various synthetic chemicals of high specificity for acarines and ticks, and farmers frequently rely on treating their animals with these materials as their default method.[23] However, the expense of labour, equipment and acaricide can sometimes upset a good balance of cost : benefit with conventional treatment methods.[24] Synthetic chemical pesticides specific for ticks (acaricides) are suspended in water for application to the hair coat of domestic animals. Cattle can be immersed in dip-baths containing dipwash, or soaked using a pressurized spray-race made of metal tubing and nozzles. Sheep can be treated in smaller dips or showers. Acaricides can be applied to dogs in watery shampoo formulations. Acaricide active ingredients are usually soluble in oil. This makes them suitable for concentrated oily formulations which spread from a pour-on applicator over the hair coat. Alternatively, some acaricides are incorporated in polyvinylchoride plastic ear tags for cattle, or collars for dogs.[25][26] Modern acaricides belong to the general classes of organophosphates (example chlorfenvinphos), formamidines (example amitraz), synthetic pyrethroids (example flumethrin), phenylpyrazoles (example fipronil), and benzylphenyl ureas (example fluazuron).[2] When correctly applied, they can be highly effective. Problems with acaricides are: danger of acute poisoning of treated animals and human staff; residues contaminating meat and milk; environmental contamination especially water sources; resistance that ticks acquire to acaricides; and cost of application. Cost and contamination can be reduced by seasonal timing of application (strategic treatment) based on ecological knowledge. Prediction of best times for treatment can be made using computerized models of the population dynamics of ticks.[27][28][29]

Botanical acaricides

Farmers lacking access to, or sufficient cash for, manufactured synthetic acaricides often use various herbal treatments, locally available. Nicotine from treated tobacco leaf is an example, but such unregistered preparations require careful use to avoid poisoning or skin damage. Commercially formulated botanical acaricide may often be available in tropical regions, containing the active ingredient azadirachtin. This is extracted as neem oil from fruits and seeds from the neem tree, Azadirachta indica.[30]

Eradication of ticks

Eradication of ticks, as total removal of all populations of a species over a wide geographical area defined by natural boundaries, has been attempted several times.[31] In the southern states of the USA the tick then known as Boophilus annulatus (Rhipicephalus annulatus) was eradicated for the purpose of control of babesiosis in cattle. The eradication was successful after more than 50 years of control with much emphasis on dipping in chemical acaricides. The tick was eradicated up to the border of USA with Mexico, and a control and quarantine zone remains in place there.[32] Similar efforts were made to eradicate the tick then known as Boophilus microplus (also a Rhipicephalus, Rhipicephalus microplus) from New South Wales, Australia. However, this failed, partly due to the difficulty of maintaining a barrier against invasions from the more favourable areas for the tick in sub-tropical Queensland.[33] Amblyomma variegatum was subject to a multi-country eradication program in the Caribbean area, but it failed for complex economic and political reasons.[34]

Biological and ecological based methods in control of ticks and transmitted microbes

Cattle breeding for disease resistance

Breeding for resistant cattle has been successful for their ability to acquire strong immune resistance to Rhipicephalus microplus following natural exposure to these ticks.[35] Commercial breeds of cattle (examples: Australian Friesian Sahiwal and Australian Milking Zebu) are successful in the relevant environment. Only a few commercial breeds of tick-resistant cattle are available. These breeds were developed under laboratory conditions where bulls were selected for good ability to acquire immune resistance to ticks, and cows were selected for heat tolerance and milk yield. The scope for selecting cattle under farm conditions includes culling those animals persistently with heavy infestations of ticks. This is due to a characteristic of many parasitic infestations where in a population of hosts, a few individual hosts carry heavy infestations, whilst the majority are lightly infested. This is called an overdispersed, or aggregated, distribution; it may be caused by individual variation in immune competence, which has a genetic component.[36]

Pasture management

For farms infested with R. microplus in Australia and South America, rotation of pasture can kill the questing larvae.[37] Pasture management is feasible for control of these one-host ticks because the only stage that quests for hosts on vegetation is the larval stage. Because of their small size, larvae are highly susceptible to dehydration and starvation, so a period without access to hosts of about 2 months can be effective. The nymphs and adults of three-host ticks, such as Amblyomma and Rhipicephalus species, can live for many months to a year or more, respectively, whilst questing on the vegetation. Thus, controlling them by pasture management is usually not practical. In addition, farmers find the priority to provide their stock with good feed often conflicts with the regimens for pasture rotation for tick control.[38] Ticks affecting dogs and other companion animals around private houses are reduced by clearing of vegetation and leaf litter, mowing grass short, and fencing out deer and other wild animals that bring in ticks.

Epidemiological factors

Compared to other arthropods of veterinary and medical importance, most species of ticks are long-lived over their whole lifecycles. Ixodes species in cool, temperate climates typically take one year to develop through each of the three feeding stages. Amblyomma species may also have a three-year lifecycle, and the adults can live off-host, without feeding, for up to 2 years. Ornithodoros and Argas ticks are particularly adapted to wait for their hosts to arrive by being able to survive for years between blood meals as adults, 18 years have been recorded for O. lahorensis.[2][39] Food reserves for survival of off-host ticks include large membrane-bound vesicles of lipid in the digestive cells of their gut. Further adaptations include a thick integument with waxy waterproofing combined with ability to secrete hygroscopic salts from specialized parts of their salivary glands (type 1 acini) out to the exterior of their mouthparts and then suck back in the watery solution that develops around the salty material.[40]

At least some species of ticks have fairly stable populations, with variations in population densities from year to year varying by roughly 10- to 100-fold.[41] The abiotic (environmental) factor that appears to have most influence on tick distribution and abundance is dehydration stress from the combination of high temperatures and low moisture (measured as relative humidity or low saturation deficit, usually resulting from a climate of low rainfall). Computer models to test hypotheses and to predict the distribution of ticks reflect these stresses, using meteorological information where available, or indices of vegetation type as an analogue of temperature and dehydration stress.[42][43] Biotic (host related) factors that influence tick distribution and abundance include the obvious need for the hosts to which the ticks are adapted to be present, and also the defenses that the hosts have against the ticks. During the lifecycle of a three-host tick feeding on its natural host that has acquired immunological resistance to the feeding of the ticks, tick mortality can be high.[44] This mortality is highest for the larvae which are easily killed by the immune reactions in the host's skin. It is lowest in the feeding adults. However, even if the ticks do feed, detach, and moult, the size of newly moulted adults is smaller, and the reproductive capacity of the females is reduced.[45] These biotic factors are likely to produce a pattern of mortality of the ticks that is density-dependent.[43] A high density of ticks attempting to feed induces strong immune resistance in their hosts, but a low density of ticks does not induce such strong resistance.

Ticks combine long life of the stages of that carry pathogenic microbes and long survival of these microbes in specialized niches within the tick, such as within cells of the salivary glands or the gut. In a population of Rhipicephalus or Hyalomma ticks feeding on cattle in which Theileria species of protozoa circulate and cause theileriosis, the ticks act as long-term reservoirs of the protozoans. In addition, some species of protozoans (within the Theileria and Babesia genera), are able to infect ticks even when they exist in the blood of their hosts at such a low level that no signs of disease can be detected. This is known as a carrier state of infection.[46][47] These pathogenic protozoa can be detected circulating in populations of the cattle hosts and tick vectors with only low levels of detectable disease in the cattle caused by the protozoa. Any situation like this - with prevalent infection or infestation but little disease - is called endemic stability.[48] It is possible that this can be exploited for better control of tick related diseases by use of breeds of cattle with good ability to acquire resistance to both the ticks and the protozoans. However, there are commonly situations where the potential benefits of endemic stability to disease are difficult for farmers to use effectively. The farmers may prefer to rely more on direct tick control, and drugs and vaccines against the protozoans.[49][50]

Drug treatment against microbes

Antibiotics with efficacy against bacterial pathogens transmitted by ticks include tetracycline, penicillin, and doxycycline. Against Babesia protozoa are imidocarb and diminazine, both of which can be used to treat patent clinical infections.[51] Against Theileria are parvaquone and halofuginone, both effective for clinical cases.[52] These drugs are usually administered to treat diagnosed cases, but the timing of treatment then becomes critical. Problems with drug treatment include the development of resistance by the microbes and cost. Also, treatment does not necessarily fully clear infections, and this may lead to persistent subclinical infections that remain infective to more ticks (carrier infections); this may be considered unsafe in some situations.[citation needed]

Vaccination against microbes and ticks

Vaccination against An. marginale is done using live strains of the cross-reactive An. centrale.[53] Vaccines are available on a commercial basis to immunize cattle against Babesia bovis.[54] This is made by serial infection of calves to attenuate the virulence of the strain of Babesia, followed by splenectomy to produce many of the piroplasm stage in blood, which is then bottled for use. The vaccine is delivered containing the live protozoa to induce immunity without acute disease.[55] Theileria annulata can be grown and attenuated in virulence by means of infecting cell cultures with the schizont stage of the protozoan. This is delivered as a frozen vaccine from which live parasites are thawed out before injection.[56][57] Cattle can be protected against East Coast fever by an infection-and-treatment procedure. Rhipicephalus appendiculatus ticks are infected with Theileria parva under laboratory conditions; theilerial sporozoites are extracted from the ticks and stored in liquid nitrogen; infective doses of the live vaccine are delivered to identified cattle and a few days later a protective dose of antibiotic is delivered to stop the infection from developing into clinical East Coast fever.[58] Vaccines are often highly effective, but the live parasite vaccines have problems of potential contamination with other microbes and induction of a carrier state which may be unwanted. Intensive attempts are made to develop vaccines to control these diseases using a recombinant DNA techniques to synthesize the relevant antigens, but as with vaccines against human malaria this is a difficult technological challenge.[59][60]

A commercial vaccine was developed in Australia against Rh. microplus.[61][62] It acts against a glycoprotein molecule that is exposed on the outer membrane of digestive cells of the gut of feeding ticks. This molecule is synthesized using recombinant DNA technique to make the antigen of the vaccine. Vaccinated cattle develop antibodies circulating in their blood. When the Rh. microplus female ticks engorge with blood, the antibody reacts with the natural antigen in their guts so strongly that digestion is disrupted and the reproductive rate of the ticks is reduced. This vaccine is manufactured in Australia and a closely similar vaccine is manufactured in Cuba.[63]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Walker, Mark David (2 November 2017). "Ticks on dogs and cats". The Veterinary Nurse 8 (9): 486–492. doi:10.12968/vetn.2017.8.9.486.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Sonenshine, D.E. (1993), Biology of ticks (vol 1). Oxford University Press, New York. ISBN:0-19-505910-7

- ↑ Guglielmone, Alberto A.; Robbins, Richard G.; Apanaskevich, Dmitry A.; Petney, Trevor N.; Estrada-Peña, Agustín; Horak, Ivan G.; Shao, Renfu; Barker, Stephen C. (6 July 2010). "The Argasidae, Ixodidae and Nuttalliellidae (Acari: Ixodida) of the world: a list of valid species names". Zootaxa 2528 (1): 1–28. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2528.1.1. http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/2010/f/z02528p028f.pdf.

- ↑ Beati, Lorenza; Keirans, James E. (February 2001). "Analysis of the systematic relationships among ticks of the genera Rhipicephalus and Boophilus (Acari: Ixodidae) based on mitochondrial 12s ribosomal DNA gene sequences and morphological characters". Journal of Parasitology 87 (1): 32–48. doi:10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[0032:AOTSRA2.0.CO;2]. PMID 11227901.

- ↑ Barker, S. C.; Murrell, A. (October 2004). "Systematics and evolution of ticks with a list of valid genus and species names". Parasitology 129 (S1): S15–S36. doi:10.1017/s0031182004005207. PMID 15938503. https://tede.ufrrj.br/bitstream/jspui/2545/2/2017%20-%20Iwine%20Joyce%20Barbosa%20de%20S%c3%a1%20Hungaro%20Faria.pdf.

- ↑ Taylor, M.A. (2007). Veterinary parasitology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-1964-1.

- ↑ Geevarghese, G; Dhanda, V (1987). The Indian Hyalomma ticks (Ixodoidea: Ixodidae). Publications and Information Division, India Council of Agricultural Research. OCLC 19554336.[page needed]

- ↑ Jonsson, N.N. (April 2006). "The productivity effects of cattle tick (Boophilus microplus) infestation on cattle, with particular reference to Bos indicus cattle and their crosses". Veterinary Parasitology 137 (1–2): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.01.010. PMID 16472920.

- ↑ Pegram, R. G.; James, A. D.; Oosterwijk, G. P. M.; Killorn, K. J.; Lemche, J.; Ghirotti, M.; Tekle, Z.; Chizyuka, H. G. B. et al. (September 1991). "Studies on the economics of ticks in Zambia". Experimental & Applied Acarology 12 (1–2): 9–26. doi:10.1007/BF01204396. PMID 1748032.

- ↑ Stachurski, F. (December 2000). "Invasion of West African cattle by the tick Amblyomma variegatum". Medical and Veterinary Entomology 14 (4): 391–399. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00246.x. PMID 11129703.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Lancaster, J.L. (1986). Arthropods in livestock and poultry production. Chichester: Ellis Horwood Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85312-790-1.[page needed]

- ↑ Gothe, Rainer; Kunze, Klaus; Hoogstraal, Harry (23 November 1979). "The Mechanisms of Pathogenicity in the Tick Paralyses". Journal of Medical Entomology 16 (5): 357–369. doi:10.1093/jmedent/16.5.357. PMID 232161.

- ↑ Stone, Bernard F.; Binnington, Keith C.; Gauci, Maryann; Aylward, James H. (June 1989). "Tick/host interactions forIxodes holocyclus: Role, effects, biosynthesis and nature of its toxic and allergenic oral secretions". Experimental & Applied Acarology 7 (1): 59–69. doi:10.1007/BF01200453. PMID 2667920.

- ↑ Barker, Stephen C.; Walker, Alan R. (18 June 2014). "Ticks of Australia. The species that infest domestic animals and humans". Zootaxa 3816 (1): 1–144. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3816.1.1. PMID 24943801. https://biotaxa.org/Zootaxa/article/download/zootaxa.3816.1.1/19356.

- ↑ Bock, R.; Jackson, L.; De Vos, A.; Jorgensen, W. (October 2004). "Babesiosis of cattle". Parasitology 129 (S1): S247–S269. doi:10.1017/s0031182004005190. PMID 15938514.

- ↑ Martinez, Dominique; Aumont, Gilles; Moutoussamy, M.; Gabriel, D.; Tatareau, A. H.; Barré, Nicolas; Vallée, F.; Mari, Bernard (1993). "Epidemiological studies on dermatophilosis in the Caribbean". Revue d'Elevage et de Médecine Vétérinaire des Pays Tropicaux 46 (1–2): 323–7. PMID 8161379. https://agritrop.cirad.fr/398696/.

- ↑ Coetzer, J.A.W. (1994). Infectious diseases of livestock with special reference to southern Africa. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-570506-5.[page needed]

- ↑ Gould, EA; Solomon, T (February 2008). "Pathogenic flaviviruses". The Lancet 371 (9611): 500–509. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60238-X. PMID 18262042.

- ↑ Hoogstraal, H (June 1979). "Ticks and spirochetes". Acta Tropica 36 (2): 133–136. doi:10.5169/seals-312515. PMID 41420.

- ↑ Uilenberg, G.; Barre, N.; Camus, E.; Burridge, M.J.; Garris, G.I. (March 1984). "Heartwater in the Caribbean". Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2 (1–4): 255–267. doi:10.1016/0167-5877(84)90068-0.

- ↑ Norval, R.A.I. (1992). The epidemiology of theileriosis in Africa. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-521740-8.[page needed]

- ↑ Katzer, F.; Ngugi, D.; Walker, A.R.; McKeever, D.J. (February 2010). "Genotypic diversity, a survival strategy for the apicomplexan parasite Theileria parva". Veterinary Parasitology 167 (2–4): 236–243. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.09.025. PMID 19837514.

- ↑ George, J. E.; Pound, J. M.; Davey, R. B. (October 2004). "Chemical control of ticks on cattle and the resistance of these parasites to acaricides". Parasitology 129 (S1): S353–S366. doi:10.1017/s0031182003004682. PMID 15938518.

- ↑ Okello-Onen, J; Mukhebi, A.W; Tukahirwa, E.M; Musisi, G; Bode, E; Heinonen, R; Perry, B.D; Opuda-Asibo, J (January 1998). "Financial analysis of dipping strategies for indigenous cattle under ranch conditions in Uganda". Preventive Veterinary Medicine 33 (1–4): 241–250. doi:10.1016/s0167-5877(97)00035-4. PMID 9500178.

- ↑ George, J. E.; Pound, J. M.; Davey, R. B. (2008). "Acaricides for controlling ticks on cattle and the problem of acaricide resistance". in Bowman, Alan S; Nuttall, Patricia A. Ticks. pp. 408–423. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511551802.019. ISBN 978-0-511-55180-2.

- ↑ Willadsen, Peter (May 2006). "Tick control: Thoughts on a research agenda". Veterinary Parasitology 138 (1–2): 161–168. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.01.050. PMID 16497440.

- ↑ Mount, G. A.; Haile, D. G.; Davey, R. B.; Cooksey, L. M. (1 March 1991). "Computer Simulation of Boophilus Cattle Tick (Acari: Ixodidae) Population Dynamics". Journal of Medical Entomology 28 (2): 223–240. doi:10.1093/jmedent/28.2.223. PMID 2056504.

- ↑ Randolph, S. E.; Rogers, D. J. (September 1997). "A generic population model for the African tick Rhipicephalus appendiculatus". Parasitology 115 (3): 265–279. doi:10.1017/s0031182097001315. PMID 9300464. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:06c3adf2-76cb-47b6-9d81-8c3470d2e63e.

- ↑ Schmidtmann, Edward T. (1994). "Ecologically based strategies for controlling ticks". in Sonenshine, Daniel E.; Mather, Thomas N.. Ecological Dynamics of Tick-borne Zoonoses. Oxford University Press. pp. 240–280. ISBN 978-0-19-507313-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=aT3nCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA240.

- ↑ Handule, Ismail Mohamed; Ketavan, Chitapa; Gebre, Solomon (31 March 2002). "Toxic Effect of Ethiopian Neem Oil on Larvae of Cattle Tick, Rhipicephalus pulchellus Gerstaeker". Agriculture and Natural Resources 36 (1): 18–22. https://li01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/anres/article/view/242682.

- ↑ Walker, Alan R. (July 2011). "Eradication and control of livestock ticks: biological, economic and social perspectives". Parasitology 138 (8): 945–959. doi:10.1017/S0031182011000709. PMID 21733257.

- ↑ Strom, C. (2009). Making catfish bait out of government boys: the fight against cattle ticks and transformation of the yeoman south. The University of Georgia Press, Athens, GA, USA and London UK. ISBN:978-0-8203-2749-5.[page needed]

- ↑ Angus, Beverley M. (December 1996). "The history of the cattle tick Boophilus microptus in Australia and achievements in its control". International Journal for Parasitology 26 (12): 1341–1355. doi:10.1016/s0020-7519(96)00112-9. PMID 9024884.

- ↑ Pegram, R. 2010. Thirteen years of hell in paradise: an account of the Caribbean Amblyomma program. Trafford Publishing, Bloomington, Indiana, USA. ISBN:978-1-4269-4453-6.[page needed]

- ↑ Hewetson, R. W. (May 1972). "The inheritance of resistance by cattle to cattle tick". Australian Veterinary Journal 48 (5): 299–303. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1972.tb05161.x. PMID 5068812.

- ↑ Shaw, D. J.; Grenfell, B. T.; Dobson, A. P. (December 1998). "Patterns of macroparasite aggregation in wildlife host populations". Parasitology 117 (6): 597–610. doi:10.1017/s0031182098003448. PMID 9881385.

- ↑ Harley, K.L.S.; Wilkinson, P.R. (1971). "A modification of pasture spelling to reduce acaricide treatments for cattle tick control". Australian Veterinary Journal 47 (3): 108–111. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1971.tb14750.x. PMID 5103591.

- ↑ Elder, J.K. (1980). "A survey concerning cattle tick control in Queensland, 4. Use of resistant cattle and pasture spelling". Australian Veterinary Journal 56 (5): 219–223. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1980.tb15976.x. PMID 7436925.

- ↑ Hoogstraal, Harry (1985). "Argasid and Nuttalliellid Ticks as Parasites and Vectors". Advances in Parasitology Volume 24. Advances in Parasitology. 24. pp. 135–238. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(08)60563-1. ISBN 978-0-12-031724-0.

- ↑ Bowman, A. S.; Ball, A.; Sauer, J. R. (2008). "Tick salivary glands: The physiology of tick water balance and their role in pathogen trafficking and transmission". in Bowman, Alan S; Nuttall, Patricia A. Ticks. pp. 73–91. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511551802.004. ISBN 978-0-511-55180-2.

- ↑ Horak, Ivan G.; Gallivan, Gordon J.; Spickett, Arthur M. (24 February 2011). "The dynamics of questing ticks collected for 164 consecutive months off the vegetation of two landscape zones in the Kruger National Park (1988–2002). Part I. Total ticks, Amblyomma hebraeum and Rhipicephalus decoloratus". Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 78 (1): 32. doi:10.4102/ojvr.v78i1.32. PMID 23327204.

- ↑ Randolph, S. E. (May 1994). "Density-dependent acquired resistance to ticks in natural hosts, independent of concurrent infection with Babesia microti". Parasitology 108 (4): 413–419. doi:10.1017/s003118200007596x. PMID 8008455.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Randolph, S. E. (2008). "The impact of tick ecology on pathogen transmission dynamics". in Bowman, Alan S; Nuttall, Patricia A. Ticks. pp. 40–72. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511551802.003. ISBN 978-0-511-55180-2.

- ↑ Utech, KBW; Wharton, RH; Kerr, JD (1978). "Resistance to Boophilus microplus (Canestrini) in different breeds of cattle". Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 29 (4): 885. doi:10.1071/ar9780885.

- ↑ Chiera, J. W.; Newson, R. M.; Cunningham, M. P. (April 1985). "Cumulative effects of host resistance on Rhipicephalus appendiculatus Neumann (Acarina: Ixodidae) in the laboratory". Parasitology 90 (2): 401–409. doi:10.1017/s003118200005109x.

- ↑ Latif, AA; Hove, T; Kanhai, GK; Masaka, S (September 2001). "Laboratory and field investigations into the Theileria parva carrier-state in cattle in Zimbabwe". The Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 68 (3): 203–208. PMID 11769352.

- ↑ Bock, R.; Jackson, L.; De Vos, A.; Jorgensen, W. (October 2004). "Babesiosis of cattle". Parasitology 129 (S1): S247–S269. doi:10.1017/s0031182004005190. ProQuest 750568336. PMID 15938514.

- ↑ Hay, Simon I. (July 2001). "The paradox of endemic stability". Trends in Parasitology 17 (7): 310. doi:10.1016/s1471-4922(01)02008-6. PMID 11423357.

- ↑ Jonsson, Nicholas N.; Bock, Russell E.; Jorgensen, Wayne K.; Morton, John M.; Stear, Michael J. (March 2012). "Is endemic stability of tick-borne disease in cattle a useful concept?". Trends in Parasitology 28 (3): 85–89. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2011.12.002. PMID 22277132.

- ↑ Rubaire-Akiiki, Christopher M.; Okello-Onen, Joseph; Musunga, David; Kabagambe, Edmond K.; Vaarst, Mettee; Okello, David; Opolot, Charles; Bisagaya, A. et al. (August 2006). "Effect of agro-ecological zone and grazing system on incidence of East Coast Fever in calves in Mbale and Sironko Districts of Eastern Uganda". Preventive Veterinary Medicine 75 (3–4): 251–266. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2006.04.015. PMID 16797092.

- ↑ Todorovic, RA; Vizcaino, OG; Gonzalez, EF; Adams, LG (September 1973). "Chemoprophylaxis (Imidocarb) against Babesia bigemina and Babesia argentina infections". American Journal of Veterinary Research 34 (9): 1153–61. PMID 4747036.

- ↑ Singh, D.K.; Thakur, M.; Raghav, P.R.S.; Varshney, B.C. (January 1993). "Chemotherapeutic trials with four drugs in crossbred calves experimentally infected with Theileria annulata". Research in Veterinary Science 54 (1): 68–71. doi:10.1016/0034-5288(93)90013-6. PMID 8434151.

- ↑ Dalgliesh, R. J.; Jorgensen, W. K.; de Vos, A. J. (March 1990). "Australian frozen vaccines for the control of babesiosis and anaplasmosis in cattle—A review". Tropical Animal Health and Production 22 (1): 44–52. doi:10.1007/BF02243499. PMID 2181745.

- ↑ de Vos, A.J. (1 December 1979). "Epidemiology and control of bovine babesiosis in South Africa". Journal of the South African Veterinary Association 50 (4): 357–362. PMID 576018. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/sabinet/savet/1979/00000050/00000004/art00034.

- ↑ Timms, P.; Dalgliesh, R. J.; Barry, D. N.; Dimmock, C. K.; Rodwell, B. J. (March 1983). "Babesia bovis: comparison of culture-derived parasites, non-living antigen and conventional vaccine in the protection of cattle against heterologous challenge". Australian Veterinary Journal 60 (3): 75–77. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1983.tb05874.x. PMID 6347164.

- ↑ Pipano, E. (March 1995). "Live vaccine against hemoparasitic disease in livestock". Veterinary Parasitology 57 (1–3): 213–231. doi:10.1016/0304-4017(94)03122-d. PMID 7597786.

- ↑ Hashemi-Fesharki, R. (February 1988). "Control of Theileria annulata in Iran". Parasitology Today 4 (2): 36–40. doi:10.1016/0169-4758(88)90062-2. PMID 15463034.

- ↑ Di Giulio, Giuseppe; Lynen, Godelieve; Morzaria, Subhash; Oura, Chris; Bishop, Richard (February 2009). "Live immunization against East Coast fever – current status". Trends in Parasitology 25 (2): 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2008.11.007. PMID 19135416.

- ↑ McKeever, D.J; Taracha, E.L.N; Morrison, W.I; Musoke, A.J; Morzaria, S.P (July 1999). "Protective Immune Mechanisms against Theileria parva: Evolution of Vaccine Development Strategies". Parasitology Today 15 (7): 263–267. doi:10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01465-9. PMID 10377527.

- ↑ Musoke, A.; Morzaria, S.; Nkonge, C.; Jones, E.; Nene, V. (15 January 1992). "A recombinant sporozoite surface antigen of Theileria parva induces protection in cattle". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 89 (2): 514–518. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.2.514. PMID 1731322. Bibcode: 1992PNAS...89..514M.

- ↑ Willadsen, Peter; Smith, Don; Cobon, Gary; McKENNA, Robert V. (May 1996). "Comparative vaccination of cattle against Boophilus microplus with recombinant antigen Bm86 alone or in combination with recombinant Bm91". Parasite Immunology 18 (5): 241–246. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3024.1996.d01-90.x. PMID 9229376.

- ↑ Willadsen, P. (2008). "Anti-tick vaccines". in Bowman, Alan S; Nuttall, Patricia A. Ticks. pp. 424–446. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511551802.020. ISBN 9780511551802.

- ↑ Delafuente, J; Rodríguez, M; Redondo, M; Montero, C; García-García, JC; Méndez, L; Serrano, E; Valdés, M et al. (February 1998). "Field studies and cost-effectiveness analysis of vaccination with Gavac? against the cattle tick Boophilus microplus". Vaccine 16 (4): 366–373. doi:10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00208-9. PMID 9607057.

External links

- Ticks. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA.

- Tick-borne Livestock Diseases and their Vectors: Five-part Series. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Ticks. Livestock Veterinary Entomology. Texas A&M AgriLife Extension.

- Tropical bont tick, Amblyomma variegatum. Prine, K. C. and A. C. Hodges. EENY-518. University of Florida IFAS. Published 2012, updated 2013.

- [1] Overview of tick paralysis.

- Parasitic Insects, Mites and Ticks: Genera of Medical and Veterinary Importance Wikibooks

Further reading

- Baker, A.S. (1999) Mites and Ticks of Domestic Animals: an identification guide and information source. London: The Stationery Office, ISBN:0-11-310049-3.

- Bowman, A. S. & Nuttall, P. A. (2008) Ticks: Biology, Disease and Control. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN:978-0-521-86761-0

- Estrada-Peña, A., Bouattour, A., Camicas, J.-L. & Walker, A.R. (2004) Ticks of domestic animals in the Mediterranean Region. University of Zaragoza, ISBN:84-96214-18-4.

- Fivaz, B., Petney, T. & Horak I. (1992) Tick vector biology: medical and veterinary aspects. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, ISBN:3-540-54045-8

- Howell C.J., Walker J.B. & Nevill E.M. (1978) Ticks, mites and insects infesting domestic animals in South Africa. Republic of South Africa Department of Agricultural Technical Services, Science Bulletin 393, Pretoria.

- Latif, A.A. (2013) Illustrated guide to identification of African tick species. Agricultural Research Council, Pretoria. ISBN:978-0-9922220-5-5

- Roberts, F.H.S. (1970) Australian ticks. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Melbourne.

- Russell, R.C., Otranto, D. & Wall R.L. (2013) The Encyclopedia of Medical and Veterinary Entomology. CABI, Wallingford. ISBN:978-1-78064-037-2.

- Slamon, M. & Tarrés-Call, J. (eds) (2013) Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases: Geographical Distribution and Control Strategies in the Euro-Asia Region. CABI, Wallingford. ISBN: 978-1-84593-853-6.

- Sonenshine, D.E. & Mather, T.N. (eds) (1994) Ecological Dynamics of Tick-borne Zoonoses. Oxford University Press, New York. ISBN:0-19-507313-4

- Sonenshine, D.E. & Roe, M.R. (eds) (2014) Biology of Ticks (2nd edition, vols 1&2) Oxford University Press, New York. vol 1 ISBN:978-0-19974405-3; vol 2 ISBN: 978-0-19-974406-0.

- Spickett, A.M. (2013) Ixodid ticks of major economic importance and their distribution in South Africa. Agricultural Research Council, Pretoria. ISBN:978-0-9922220-4-8

- Walker, A.R., Bouattour, A., Camicas, J.-L., Estrada-Peña, A., Horak, I.G., Latif, A.A., Pegram, R.G. & Preston, P.M. 2003. Ticks of domestic animals in Africa: a guide to identification of species. Bioscience Reports, Edinburgh. ISBN:0-9545173-0-X, http://www.alanrwalker.com/guidebooks/ticks/

Gallery

|