Camassa–Holm equation

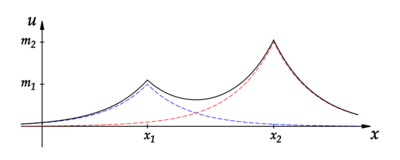

[math]\displaystyle{ u = m_1 \, e^{-|x-x_1|} + m_2 \, e^{-|x-x_2|}. }[/math]

The evolution of the individual peakon positions [math]\displaystyle{ x_1(t) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ x_2(t) }[/math], as well as the evolution of the peakon amplitudes [math]\displaystyle{ m_1(t) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ m_2(t), }[/math] is however less trivial: this is determined in a non-linear fashion by the interaction.

In fluid dynamics, the Camassa–Holm equation is the integrable, dimensionless and non-linear partial differential equation

- [math]\displaystyle{ u_t + 2\kappa u_x - u_{xxt} + 3 u u_x = 2 u_x u_{xx} + u u_{xxx}. \, }[/math]

The equation was introduced by Roberto Camassa and Darryl Holm[1] as a bi-Hamiltonian model for waves in shallow water, and in this context the parameter κ is positive and the solitary wave solutions are smooth solitons.

In the special case that κ is equal to zero, the Camassa–Holm equation has peakon solutions: solitons with a sharp peak, so with a discontinuity at the peak in the wave slope.

Relation to waves in shallow water

The Camassa–Holm equation can be written as the system of equations:[2]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} u_t + u u_x + p_x &= 0, \\ p - p_{xx} &= 2 \kappa u + u^2 + \frac{1}{2} \left( u_x \right)^2, \end{align} }[/math]

with p the (dimensionless) pressure or surface elevation. This shows that the Camassa–Holm equation is a model for shallow water waves with non-hydrostatic pressure and a water layer on a horizontal bed.

The linear dispersion characteristics of the Camassa–Holm equation are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \omega = 2\kappa \frac{k}{1+k^2}, }[/math]

with ω the angular frequency and k the wavenumber. Not surprisingly, this is of similar form as the one for the Korteweg–de Vries equation, provided κ is non-zero. For κ equal to zero, the Camassa–Holm equation has no frequency dispersion — moreover, the linear phase speed is zero for this case. As a result, κ is the phase speed for the long-wave limit of k approaching zero, and the Camassa–Holm equation is (if κ is non-zero) a model for one-directional wave propagation like the Korteweg–de Vries equation.

Hamiltonian structure

Introducing the momentum m as

- [math]\displaystyle{ m = u - u_{xx} + \kappa, \, }[/math]

then two compatible Hamiltonian descriptions of the Camassa–Holm equation are:[3]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} m_t &= -\mathcal{D}_1 \frac{\delta \mathcal{H}_1}{\delta m} & & \text{ with }& \mathcal{D}_1 &= m \frac{\partial}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial}{\partial x} m & \text{ and } \mathcal{H}_1 &= \frac{1}{2} \int u^2 + \left(u_x\right)^2\; \text{d}x, \\ m_t &= -\mathcal{D}_2 \frac{\delta \mathcal{H}_2}{\delta m} & & \text{ with }& \mathcal{D}_2 &= \frac{\partial}{\partial x} - \frac{\partial^3}{\partial x^3} & \text{ and } \mathcal{H}_2 &= \frac{1}{2} \int u^3 + u \left(u_{x}\right)^2 - \kappa u^2\; \text{d}x. \end{align} }[/math]

Integrability

The Camassa–Holm equation is an integrable system. Integrability means that there is a change of variables (action-angle variables) such that the evolution equation in the new variables is equivalent to a linear flow at constant speed. This change of variables is achieved by studying an associated isospectral/scattering problem, and is reminiscent of the fact that integrable classical Hamiltonian systems are equivalent to linear flows at constant speed on tori. The Camassa–Holm equation is integrable provided that the momentum

- [math]\displaystyle{ m= u-u_{xx}+ \kappa \, }[/math]

is positive — see [4] and [5] for a detailed description of the spectrum associated to the isospectral problem,[4] for the inverse spectral problem in the case of spatially periodic smooth solutions, and [6] for the inverse scattering approach in the case of smooth solutions that decay at infinity.

Exact solutions

Traveling waves are solutions of the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ u(t,x)=f(x-ct) \, }[/math]

representing waves of permanent shape f that propagate at constant speed c. These waves are called solitary waves if they are localized disturbances, that is, if the wave profile f decays at infinity. If the solitary waves retain their shape and speed after interacting with other waves of the same type, we say that the solitary waves are solitons. There is a close connection between integrability and solitons.[7] In the limiting case when κ = 0 the solitons become peaked (shaped like the graph of the function f(x) = e−|x|), and they are then called peakons. It is possible to provide explicit formulas for the peakon interactions, visualizing thus the fact that they are solitons.[8] For the smooth solitons the soliton interactions are less elegant.[9] This is due in part to the fact that, unlike the peakons, the smooth solitons are relatively easy to describe qualitatively — they are smooth, decaying exponentially fast at infinity, symmetric with respect to the crest, and with two inflection points[10] — but explicit formulas are not available. Notice also that the solitary waves are orbitally stable i.e. their shape is stable under small perturbations, both for the smooth solitons[10] and for the peakons.[11]

Wave breaking

The Camassa–Holm equation models breaking waves: a smooth initial profile with sufficient decay at infinity develops into either a wave that exists for all times or into a breaking wave (wave breaking[12] being characterized by the fact that the solution remains bounded but its slope becomes unbounded in finite time). The fact that the equations admits solutions of this type was discovered by Camassa and Holm[1] and these considerations were subsequently put on a firm mathematical basis.[13] It is known that the only way singularities can occur in solutions is in the form of breaking waves.[14][15] Moreover, from the knowledge of a smooth initial profile it is possible to predict (via a necessary and sufficient condition) whether wave breaking occurs or not.[16] As for the continuation of solutions after wave breaking, two scenarios are possible: the conservative case[17] and the dissipative case[18] (with the first characterized by conservation of the energy, while the dissipative scenario accounts for loss of energy due to breaking).

Long-time asymptotics

It can be shown that for sufficiently fast decaying smooth initial conditions with positive momentum splits into a finite number and solitons plus a decaying dispersive part. More precisely, one can show the following for [math]\displaystyle{ \kappa\gt 0 }[/math]:[19] Abbreviate [math]\displaystyle{ c =x / (\kappa t) }[/math]. In the soliton region [math]\displaystyle{ c\gt 2 }[/math] the solutions splits into a finite linear combination solitons. In the region [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt c\lt 2 }[/math] the solution is asymptotically given by a modulated sine function whose amplitude decays like [math]\displaystyle{ t^{-1/2} }[/math]. In the region [math]\displaystyle{ -1/4\lt c\lt 0 }[/math] the solution is asymptotically given by a sum of two modulated sine function as in the previous case. In the region [math]\displaystyle{ c\lt -1/4 }[/math] the solution decays rapidly. In the case [math]\displaystyle{ \kappa=0 }[/math] the solution splits into an infinite linear combination of peakons[20] (as previously conjectured[21]).

Geometric formulation

In the spatially periodic case, the Camassa–Holm equation can be given the following geometric interpretation. The group [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{Diff}(S^1) }[/math] of diffeomorphisms of the unit circle [math]\displaystyle{ S^1 }[/math] is an infinite-dimensional Lie group whose Lie algebra [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{Vect}(S^1) }[/math] consists of smooth vector fields on [math]\displaystyle{ S^1 }[/math].[22] The [math]\displaystyle{ H^1 }[/math] inner product on [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{Vect}(S^1) }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left\langle u \frac{\partial}{\partial x} , v\frac{\partial}{\partial x} \right\rangle_{H^1} = \int_{S^1}(uv+u_xv_x)dx, }[/math]

induces a right-invariant Riemannian metric on [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{Diff}(S^1) }[/math]. Here [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] is the standard coordinate on [math]\displaystyle{ S^1 }[/math]. Let

- [math]\displaystyle{ U(x,t)=u(x,t)\frac{\partial}{\partial x} }[/math]

be a time-dependent vector field on [math]\displaystyle{ S^1 }[/math], and let [math]\displaystyle{ \{\varphi_t\} }[/math] be the flow of [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math], i.e. the solution to

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{d}{dt}\varphi_t(x)=u(\varphi_t(x),t). }[/math]

Then [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] is a solution to the Camassa–Holm equation with [math]\displaystyle{ \kappa=0 }[/math], if and only if the path [math]\displaystyle{ t\mapsto\varphi_t\in\mathrm{Diff}(S^1) }[/math] is a geodesic on [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{Diff}(S^1) }[/math] with respect to the right-invariant [math]\displaystyle{ H^1 }[/math] metric.[23]

For general [math]\displaystyle{ \kappa }[/math], the Camassa–Holm equation corresponds to the geodesic equation of a similar right-invariant metric on the universal central extension of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{Diff}(S^1) }[/math], the Virasoro group.

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Camassa & Holm 1993.

- ↑ Loubet 2005.

- ↑ Boldea 1995.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Constantin & McKean 1999.

- ↑ Constantin 2001.

- ↑ Constantin, Gerdjikov & Ivanov 2006.

- ↑ Drazin & Johnson 1989.

- ↑ Beals, Sattinger & Szmigielski 1999.

- ↑ Parker 2005.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Constantin & Strauss 2002.

- ↑ Constantin & Strauss 2000.

- ↑ Whitham 1974.

- ↑ Constantin & Escher 1998.

- ↑ Constantin 2000.

- ↑ Constantin & Escher 2000.

- ↑ McKean 2004.

- ↑ Bressan & Constantin 2007a.

- ↑ Bressan & Constantin 2007b.

- ↑ Boutet de Monvel et al. 2009.

- ↑ Eckhardt & Teschl 2013.

- ↑ McKean 2003.

- ↑ Kriegl & Michor 1997.

- ↑ Misiołek 1998.

References

- Beals, Richard; Sattinger, David H.; Szmigielski, Jacek (1999), "Multi-peakons and a theorem of Stieltjes", Inverse Problems 15 (1): L1–L4, doi:10.1088/0266-5611/15/1/001, Bibcode: 1999InvPr..15L...1B

- Boldea, Costin-Radu (1995), "A generalization for peakon's solitary wave and Camassa–Holm equation", General Mathematics 5 (1–4): 33–42, http://www.emis.de/journals/GM/vol5/bold.html

- Boutet de Monvel; Kostenko, Aleksey; Shepelsky, Dmitry; Teschl, Gerald (2009), "Long-Time Asymptotics for the Camassa–Holm Equation", SIAM Journal on Mathematical Analysis 41 (4): 1559–1588, doi:10.1137/090748500

- Bressan, Alberto; Constantin, Adrian (2007a), "Global conservative solutions of the Camassa–Holm equation", Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis 183 (2): 215–239, doi:10.1007/s00205-006-0010-z, Bibcode: 2007ArRMA.183..215B, http://www.math.ntnu.no/conservation/2005/016.html

- Bressan, Alberto; Constantin, Adrian (2007b), "Global dissipative solutions of the Camassa–Holm equation", Analysis and Applications 5: 1–27, doi:10.1142/S0219530507000857, http://www.math.ntnu.no/conservation/2006/023.html

- Camassa, Roberto; Holm, Darryl D. (1993), "An integrable shallow water equation with peaked solitons", Physical Review Letters 71 (11): 1661–1664, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.1661, PMID 10054466, Bibcode: 1993PhRvL..71.1661C

- Constantin, Adrian (2000), "Existence of permanent and breaking waves for a shallow water equation: a geometric approach", Annales de l'Institut Fourier 50 (2): 321–362, doi:10.5802/aif.1757, http://www.numdam.org/item?id=AIF_2000__50_2_321_0

- Constantin, Adrian (2001), "On the scattering problem for the Camassa–Holm equation", Proceedings of the Royal Society A 457 (2008): 953–970, doi:10.1098/rspa.2000.0701, Bibcode: 2001RSPSA.457..953C

- Constantin, Adrian; Escher, Joachim (1998), "Wave breaking for nonlinear nonlocal shallow water equations", Acta Mathematica 181 (2): 229–243, doi:10.1007/BF02392586

- Constantin, Adrian; Escher, Joachim (2000), "On the blow-up rate and the blow-up set of breaking waves for a shallow water equation", Mathematische Zeitschrift 233 (1): 75–91, doi:10.1007/PL00004793

- Constantin, Adrian; McKean, Henry P. (1999), "A shallow water equation on the circle", Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 52 (8): 949–982, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0312(199908)52:8<949::AID-CPA3>3.0.CO;2-D

- Constantin, Adrian; Strauss, Walter A. (2000), "Stability of peakons", Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 53 (5): 603–610, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0312(200005)53:5<603::AID-CPA3>3.0.CO;2-L

- Constantin, Adrian; Strauss, Walter A. (2002), "Stability of the Camassa–Holm solitons", Journal of Nonlinear Science 12 (4): 415–422, doi:10.1007/s00332-002-0517-x, Bibcode: 2002JNS....12..415C

- Constantin, Adrian; Gerdjikov, Vladimir S.; Ivanov, Rossen I. (2006), "Inverse scattering transform for the Camassa–Holm equation", Inverse Problems 22 (6): 2197–2207, doi:10.1088/0266-5611/22/6/017, Bibcode: 2006InvPr..22.2197C

- Drazin, P. G.; Johnson, R. S. (1989), Solitons: an introduction, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Eckhardt, Jonathan; Teschl, Gerald (2013), "On the isospectral problem of the dispersionless Camassa-Holm equation", Advances in Mathematics 235 (1): 469–495, doi:10.1016/j.aim.2012.12.006

- Kriegl, Andreas; Michor, Peter W. (1997), The convenient setting of global analysis, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, pp. 454–456, ISBN 0-8218-0780-3, OCLC 37141279, https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/37141279

- Loubet, Enrique (2005), "About the explicit characterization of Hamiltonians of the Camassa–Holm hierarchy", Journal of Nonlinear Mathematical Physics 12 (1): 135–143, doi:10.2991/jnmp.2005.12.1.11, Bibcode: 2005JNMP...12..135L, https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/21734/1/121art7.pdf

- McKean, Henry P. (2003), "Fredholm determinants and the Camassa–Holm hierarchy", Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 56 (5): 638–680, doi:10.1002/cpa.10069

- McKean, Henry P. (2004), "Breakdown of the Camassa–Holm equation", Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 57 (3): 416–418, doi:10.1002/cpa.20003

- Misiołek, Gerard (1998), "A shallow water equation as a geodesic flow on the Bott-Virasoro group", Journal of Geometry and Physics 24 (3): 203–208, doi:10.1016/S0393-0440(97)00010-7, Bibcode: 1998JGP....24..203M

- Parker, Allen (2005), "On the Camassa–Holm equation and a direct method of solution. III. N-soliton solutions", Proceedings of the Royal Society A 461 (2064): 3893–3911, doi:10.1098/rspa.2005.1537, Bibcode: 2005RSPSA.461.3893P

- Whitham, G. B. (1974), Linear and nonlinear waves, New York; London; Sydney: Wiley Interscience

Further reading

- Peakon solutions

- Beals, Richard; Sattinger, David H.; Szmigielski, Jacek (2000), "Multipeakons and the classical moment problem", Advances in Mathematics 154 (2): 229–257, doi:10.1006/aima.1999.1883

- Water wave theory

- Constantin, Adrian; Lannes, David (2007), "The hydrodynamical relevance of the Camassa–Holm and Degasperis–Procesi equations", Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis 192 (1): 165–186, doi:10.1007/s00205-008-0128-2, Bibcode: 2009ArRMA.192..165C

- Johnson, Robin S. (2003b), "The classical problem of water waves: a reservoir of integrable and nearly-integrable equations", J. Nonlinear Math. Phys. 10 (suppl. 1): 72–92, doi:10.2991/jnmp.2003.10.s1.6, Bibcode: 2003JNMP...10S..72J

- Existence, uniqueness, wellposedness, stability, propagation speed, etc.

- Bressan, Alberto; Constantin, Adrian (2007a), "Global conservative solutions of the Camassa–Holm equation", Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 183 (2): 215–239, doi:10.1007/s00205-006-0010-z, Bibcode: 2007ArRMA.183..215B, http://www.math.ntnu.no/conservation/2005/016.html

- Constantin, Adrian; Strauss, Walter A. (2000), "Stability of peakons", Comm. Pure Appl. Math. 53 (5): 603–610, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0312(200005)53:5<603::AID-CPA3>3.0.CO;2-L

- Holden, Helge; Raynaud, Xavier (2007a), "Global conservative multipeakon solutions of the Camassa–Holm equation", J. Hyperbolic Differ. Equ. 4 (1): 39–64, doi:10.1142/S0219891607001045, http://www.math.ntnu.no/conservation/2006/011.html

- McKean, Henry P. (2004), "Breakdown of the Camassa–Holm equation", Comm. Pure Appl. Math. 57 (3): 416–418, doi:10.1002/cpa.20003

- Travelling waves

- Lenells, Jonatan (2005c), "Traveling wave solutions of the Camassa–Holm equation", J. Differential Equations 217 (2): 393–430, doi:10.1016/j.jde.2004.09.007, Bibcode: 2005JDE...217..393L

- Integrability structure (symmetries, hierarchy of soliton equations, conservations laws) and differential-geometric formulation

- Fuchssteiner, Benno (1996), "Some tricks from the symmetry-toolbox for nonlinear equations: generalizations of the Camassa–Holm equation", Physica D 95 (3–4): 229–243, doi:10.1016/0167-2789(96)00048-6, Bibcode: 1996PhyD...95..229F

- Lenells, Jonatan (2005a), "Conservation laws of the Camassa–Holm equation", J. Phys. A 38 (4): 869–880, doi:10.1088/0305-4470/38/4/007, Bibcode: 2005JPhA...38..869L

- McKean, Henry P. (2003b), "The Liouville correspondence between the Korteweg–de Vries and the Camassa–Holm hierarchies", Comm. Pure Appl. Math. 56 (7): 998–1015, doi:10.1002/cpa.10083

- Misiołek, Gerard (1998), "A shallow water equation as a geodesic flow on the Bott–Virasoro group", J. Geom. Phys. 24 (3): 203–208, doi:10.1016/S0393-0440(97)00010-7, Bibcode: 1998JGP....24..203M

- Abenda, Simonetta; Grava, Tamara (2005), "Modulation of Camassa–Holm equation and reciprocal transformations", Annales de l'Institut Fourier 55 (6): 1803–1834, doi:10.5802/aif.2142, Bibcode: 2005math.ph...6042A

- Alber, Mark S.; Camassa, Roberto; Holm, Darryl D.; Marsden, Jerrold E. (1994), "The geometry of peaked solitons and billiard solutions of a class of integrable PDEs", Lett. Math. Phys. 32 (2): 137–151, doi:10.1007/BF00739423, Bibcode: 1994LMaPh..32..137A

- Alber, Mark S.; Camassa, Roberto; Holm, Darryl D.; Fedorov, Yuri N.; Marsden, Jerrold E. (2001), "The complex geometry of weak piecewise smooth solutions of integrable nonlinear PDE's of shallow water and Dym type", Comm. Math. Phys. 221 (1): 197–227, doi:10.1007/PL00005573, Bibcode: 2001CMaPh.221..197A

- Artebrant, Robert; Schroll, Hans Joachim (2006), "Numerical simulation of Camassa–Holm peakons by adaptive upwinding", Applied Numerical Mathematics 56 (5): 695–711, doi:10.1016/j.apnum.2005.06.002

- Beals, Richard; Sattinger, David H.; Szmigielski, Jacek (2005), "Periodic peakons and Calogero–Françoise flows", J. Inst. Math. Jussieu 4 (1): 1–27, doi:10.1017/S1474748005000010

- Boutet de Monvel, Anne; Shepelsky, Dmitry (2005), "The Camassa–Holm equation on the half-line", C. R. Math. Acad. Sci. Paris 341 (10): 611–616, doi:10.1016/j.crma.2005.09.035, http://www.numdam.org/articles/10.1016/j.crma.2005.09.035/

- Boutet de Monvel, Anne; Shepelsky, Dmitry (2006), "Riemann–Hilbert approach for the Camassa–Holm equation on the line", C. R. Math. Acad. Sci. Paris 343 (10): 627–632, doi:10.1016/j.crma.2006.10.014, http://www.numdam.org/articles/10.1016/j.crma.2006.10.014/

- Boyd, John P. (2005), "Near-corner waves of the Camassa–Holm equation", Physics Letters A 336 (4–5): 342–348, doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2004.12.055, Bibcode: 2005PhLA..336..342B

- Byers, Peter (2006), "Existence time for the Camassa–Holm equation and the critical Sobolev index", Indiana Univ. Math. J. 55 (3): 941–954, doi:10.1512/iumj.2006.55.2710

- Camassa, Roberto (2003), "Characteristics and the initial value problem of a completely integrable shallow water equation", Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. Ser. B 3 (1): 115–139, doi:10.3934/dcdsb.2003.3.115

- Camassa, Roberto; Holm, Darryl D.; Hyman, J. M. (1994), "Advances in Applied Mechanics Volume 31", Adv. Appl. Mech. 31: 1–33, doi:10.1016/S0065-2156(08)70254-0, ISBN 9780120020317

- Camassa, Roberto; Huang, Jingfang; Lee, Long (2005), "On a completely integrable numerical scheme for a nonlinear shallow-water wave equation", J. Nonlinear Math. Phys. 12 (suppl. 1): 146–162, doi:10.2991/jnmp.2005.12.s1.13, Bibcode: 2005JNMP...12S.146C

- Camassa, Roberto; Huang, Jingfang; Lee, Long (2006), "Integral and integrable algorithms for a nonlinear shallow-water wave equation", J. Comput. Phys. 216 (2): 547–572, doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2005.12.013, Bibcode: 2006JCoPh.216..547C

- Casati, Paolo; Lorenzoni, Paolo; Ortenzi, Giovanni; Pedroni, Marco (2005), "On the local and nonlocal Camassa–Holm hierarchies", J. Math. Phys. 46 (4): 042704, 8 pp, doi:10.1063/1.1888568, Bibcode: 2005JMP....46d2704C

- Coclite, Giuseppe Maria; Karlsen, Kenneth Hvistendahl (2006), "A singular limit problem for conservation laws related to the Camassa–Holm shallow water equation", Comm. Partial Differential Equations 31 (7–9): 1253–1272, doi:10.1080/03605300600781600, http://www.math.ntnu.no/conservation/2005/017.html

- Coclite, Giuseppe Maria; Karlsen, Kenneth Hvistendahl; Risebro, Nils Henrik (2008a), "A convergent finite difference scheme for the Camassa–Holm equation with general H1 initial data", SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 46 (3): 1554–1579, doi:10.1137/060673242, http://www.math.ntnu.no/conservation/2006/038.html

- Coclite, Giuseppe Maria; Karlsen, Kenneth Hvistendahl; Risebro, Nils Henrik (2008b), "An explicit finite difference scheme for the Camassa–Holm equation", arXiv:0802.3129 [math.AP]

- Cohen, David; Owren, Brynjulf; Raynaud, Xavier (2008), "Multi-symplectic integration of the Camassa–Holm equation", Journal of Computational Physics 227 (11): 5492–5512, doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2008.01.051, Bibcode: 2008JCoPh.227.5492C

- Constantin, Adrian (1997), "The Hamiltonian structure of the Camassa–Holm equation", Exposition. Math. 15 (1): 53–85

- Constantin, Adrian (1998), "On the inverse spectral problem for the Camassa–Holm equation", J. Funct. Anal. 155 (2): 352–363, doi:10.1006/jfan.1997.3231

- Constantin, Adrian (2005), "Finite propagation speed for the Camassa–Holm equation", J. Math. Phys. 46 (2): 023506, 4 pp, doi:10.1063/1.1845603, Bibcode: 2005JMP....46b3506C

- Constantin, Adrian; Escher, Joachim (1998a), "Global existence and blow-up for a shallow water equation", Ann. Scuola Norm. Sup. Pisa Cl. Sci. 26 (2): 303–328, http://www.numdam.org/item?id=ASNSP_1998_4_26_2_303_0

- Constantin, Adrian; Escher, Joachim (1998c), "Well-posedness, global existence, and blowup phenomena for a periodic quasi-linear hyperbolic equation", Comm. Pure Appl. Math. 51 (5): 475–504, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0312(199805)51:5<475::AID-CPA2>3.0.CO;2-5

- Constantin, Adrian; Gerdjikov, Vladimir S.; Ivanov, Rossen I. (2007), "Generalized Fourier transform for the Camassa–Holm hierarchy", Inverse Problems 23 (4): 1565–1597, doi:10.1088/0266-5611/23/4/012, Bibcode: 2007InvPr..23.1565C

- Constantin, Adrian; Ivanov, Rossen (2006), "Poisson structure and action-angle variables for the Camassa–Holm equation", Lett. Math. Phys. 76 (1): 93–108, doi:10.1007/s11005-006-0063-9, Bibcode: 2006LMaPh..76...93C

- Constantin, Adrian; Kolev, Boris (2003), "Geodesic flow on the diffeomorphism group of the circle", Comment. Math. Helv. 78 (4): 787–804, doi:10.1007/s00014-003-0785-6

- Constantin, Adrian; Molinet, Luc (2000), "Global weak solutions for a shallow water equation", Comm. Math. Phys. 211 (1): 45–61, doi:10.1007/s002200050801, Bibcode: 2000CMaPh.211...45C

- Constantin, Adrian; Molinet, Luc (2001), "Orbital stability of solitary waves for a shallow water equation", Phys. D 157 (1–2): 75–89, doi:10.1016/S0167-2789(01)00298-6, Bibcode: 2001PhyD..157...75C

- Dai, Hui-Hui (1998), "Model equations for nonlinear dispersive waves in a compressible Mooney–Rivlin rod", Acta Mech. 127 (1–4): 193–207, doi:10.1007/BF01170373

- Dai, Hui-Hui; Pavlov, Maxim (1998), "Transformations for the Camassa–Holm equation, its high-frequency limit and the sinh-Gordon equation", J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 67 (11): 3655–3657, doi:10.1143/JPSJ.67.3655, Bibcode: 1998JPSJ...67.3655D

- Danchin, Raphaël (2001), "A few remarks on the Camassa–Holm equation", Differential Integral Equations 14 (8): 953–988

- Danchin, Raphaël (2003), "A note on well-posedness for Camassa–Holm equation", J. Differential Equations 192 (2): 429–444, doi:10.1016/S0022-0396(03)00096-2, Bibcode: 2003JDE...192..429D

- Escher, Joachim; Yin, Zhaoyang (2008), "Initial boundary value problems of the Camassa–Holm equation", Comm. Partial Differential Equations 33 (1–3): 377–395, doi:10.1080/03605300701318872

- Fisher, Michael; Schiff, Jeremy (1999), "The Camassa–Holm equation: conserved quantities and the initial value problem", Phys. Lett. A 259 (5): 371–376, doi:10.1016/S0375-9601(99)00466-1, Bibcode: 1999PhLA..259..371F

- Fuchssteiner, Benno (1981), "The Lie algebra structure of nonlinear evolution equations admitting infinite-dimensional abelian symmetry groups", Progr. Theoret. Phys. 65 (3): 861–876, doi:10.1143/PTP.65.861, Bibcode: 1981PThPh..65..861F

- Fuchssteiner, Benno; Fokas, Athanassios S. (1981), "Symplectic structures, their Bäcklund transformations and hereditary symmetries", Physica D 4 (1): 47–66, doi:10.1016/0167-2789(81)90004-X, Bibcode: 1981PhyD....4...47F

- Gesztesy, Fritz; Holden, Helge (2003), "Algebro-geometric solutions of the Camassa–Holm hierarchy", Rev. Mat. Iberoamericana 19 (1): 73–142, http://projecteuclid.org/getRecord?id=euclid.rmi/1049123081

- Golovko, V.; Kersten, P.; Krasil'shchik, I.; Verbovetsky, A. (2008), "On integrability of the Camassa–Holm equation and its invariants: a geometrical approach", Acta Appl. Math. 101 (1–3): 59–83, doi:10.1007/s10440-008-9200-z

- Himonas, A. Alexandrou; Misiołek, Gerard (2001), "The Cauchy problem for an integrable shallow-water equation", Differential and Integral Equations 14 (7): 821–831

- Himonas, A. Alexandrou; Misiołek, Gerard (2005), "High-frequency smooth solutions and well-posedness of the Camassa–Holm equation", Int. Math. Res. Not. 2005 (51): 3135–3151, doi:10.1155/IMRN.2005.3135

- Himonas, A. Alexandrou; Misiołek, Gerard; Ponce, Gustavo; Zhou, Yong (2007), "Persistence properties and unique continuation of solutions of the Camassa–Holm equation", Comm. Math. Phys. 271 (2): 511–522, doi:10.1007/s00220-006-0172-4, Bibcode: 2007CMaPh.271..511H

- Holden, Helge; Raynaud, Xavier (2006a), "A convergent numerical scheme for the Camassa–Holm equation based on multipeakons", Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. 14 (3): 505–523, doi:10.3934/dcds.2006.14.505, http://www.math.ntnu.no/conservation/2005/004.html

- Holden, Helge; Raynaud, Xavier (2006b), "Convergence of a finite difference scheme for the Camassa–Holm equation", SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 44 (4): 1655–1680, doi:10.1137/040611975, http://www.math.ntnu.no/conservation/2004/038.html

- Holden, Helge; Raynaud, Xavier (2008a), "Periodic conservative solutions of the Camassa–Holm equation", Annales de l'Institut Fourier 58 (3): 945–988, doi:10.5802/aif.2375, http://www.math.ntnu.no/conservation/2006/035.html

- Holden, Helge; Raynaud, Xavier (2007b), "Global conservative solutions of the Camassa–Holm equation—a Lagrangian point of view", Communications in Partial Differential Equations 32 (10–12): 1511–1549, doi:10.1080/03605300601088674, http://www.math.ntnu.no/conservation/2006/001.html

- Holden, Helge; Raynaud, Xavier (2008), Dissipative solutions for the Camassa–Holm equation, http://www.math.ntnu.no/conservation/2008/012.html

- Hwang, Seok (2007), "Singular limit problem of the Camassa–Holm type equation", Journal of Differential Equations 235 (1): 74–84, doi:10.1016/j.jde.2006.12.011, Bibcode: 2007JDE...235...74H

- Ionescu-Kruse, Delia (2007), "Variational derivation of the Camassa–Holm shallow water equation with non-zero vorticity", Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. 19 (3): 531–543, doi:10.3934/dcds.2007.19.531, Bibcode: 2007arXiv0711.4701I, http://www.aimsciences.org/journals/displayPapers.jsp?comments=Special%20Issue%20on%20%3Cbr%3E%20Geometric%20Mechanics&pubID=197&journID=1&pubString=Volume:%2019,%20Number:%203,%20November%202007, retrieved 2009-02-19

- Johnson, Robin S. (2002), "Camassa–Holm, Korteweg–de Vries and related models for water waves", J. Fluid Mech. 455 (1): 63–82, doi:10.1017/S0022112001007224, Bibcode: 2002JFM...455...63J

- Johnson, Robin S. (2003a), "The Camassa–Holm equation for water waves moving over a shear flow", Fluid Dynam. Res. 33 (1–2): 97–111, doi:10.1016/S0169-5983(03)00036-4, Bibcode: 2003FlDyR..33...97J

- Johnson, Robin S. (2003c), "On solutions of the Camassa–Holm equation", R. Soc. Lond. Proc. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 459 (2035): 1687–1708, doi:10.1098/rspa.2002.1078, Bibcode: 2003RSPSA.459.1687J

- Kaup, D. J. (2006), "Evolution of the scattering coefficients of the Camassa–Holm equation, for general initial data", Stud. Appl. Math. 117 (2): 149–164, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9590.2006.00350.x

- Khesin, Boris; Misiołek, Gerard (2003), "Euler equations on homogeneous spaces and Virasoro orbits", Advances in Mathematics 176 (1): 116–144, doi:10.1016/S0001-8708(02)00063-4

- de Lellis, Camillo; Kappeler, Thomas; Topalov, Peter (2007), "Low-regularity solutions of the periodic Camassa–Holm equation", Communications in Partial Differential Equations 32 (1–3): 87–126, doi:10.1080/03605300601091470

- Lenells, Jonatan (2004), "A variational approach to the stability of periodic peakons", J. Nonlinear Math. Phys. 11 (2): 151–163, doi:10.2991/jnmp.2004.11.2.2, Bibcode: 2004JNMP...11..151L

- Lenells, Jonatan (2004), "Stability of periodic peakons", International Mathematics Research Notices 2004 (10): 485–499, doi:10.1155/S1073792804132431

- Lenells, Jonatan (2004), "The correspondence between KdV and Camassa–Holm", International Mathematics Research Notices 2004 (71): 3797–3811, doi:10.1155/S1073792804142451

- Lenells, Jonatan (2005), "Stability for the periodic Camassa–Holm equation", Mathematica Scandinavica 97 (2): 188–200, doi:10.7146/math.scand.a-14971

- Lenells, Jonatan (2007), "Infinite propagation speed of the Camassa–Holm equation", J. Math. Anal. Appl. 325 (2): 1468–1478, doi:10.1016/j.jmaa.2006.02.045

- Li, Luen-Chau (2008), "Factorization problem on the Hilbert–Schmidt group and the Camassa–Holm equation", Comm. Pure Appl. Math. 61 (2): 186–209, doi:10.1002/cpa.20207

- Liao (2013), "Do peaked solitary water waves indeed exist?", Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation 19 (6): 1792–1821, doi:10.1016/j.cnsns.2013.09.042, Bibcode: 2014CNSNS..19.1792L

- Lombardo, Maria Carmela; Sammartino, Marco; Sciacca, Vincenzo (2005), "A note on the analytic solutions of the Camassa–Holm equation", C. R. Math. Acad. Sci. Paris 341 (11): 659–664, doi:10.1016/j.crma.2005.10.006, http://www.numdam.org/articles/10.1016/j.crma.2005.10.006/

- Loubet, Enrique (2006), "Genesis of solitons arising from individual flows of the Camassa–Holm hierarchy", Comm. Pure Appl. Math. 59 (3): 408–465, doi:10.1002/cpa.20109

- Misiołek, Gerard (2005), "Classical solutions of the periodic Camassa–Holm equation", Geometric and Functional Analysis 12 (5): 1080–1104, doi:10.1007/PL00012648

- Olver, Peter J.; Rosenau, Philip (1996), "Tri-Hamiltonian duality between solitons and solitary-wave solutions having compact support", Phys. Rev. E 53 (2): 1900–1906, doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.53.1900, PMID 9964452, Bibcode: 1996PhRvE..53.1900O

- Ortenzi, Giovanni; Pedroni, Marco; Rubtsov, Vladimir (2008), "On the higher Poisson structures of the Camassa–Holm hierarchy", Acta Appl. Math. 101 (1–3): 243–254, doi:10.1007/s10440-008-9188-4

- Parker, Allen (2004), "On the Camassa–Holm equation and a direct method of solution. I. Bilinear form and solitary waves", Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 460 (2050): 2929–2957, doi:10.1098/rspa.2004.1301, Bibcode: 2004RSPSA.460.2929P

- Parker, Allen (2005), "On the Camassa–Holm equation and a direct method of solution. II. Soliton solutions", Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 461 (2063): 3611–3632, doi:10.1098/rspa.2005.1536, Bibcode: 2005RSPSA.461.3611P

- Parker, Allen (2006), "A factorization procedure for solving the Camassa–Holm equation", Inverse Problems 22 (2): 599–609, doi:10.1088/0266-5611/22/2/013, Bibcode: 2006InvPr..22..599P

- Parker, Allen (2007), "Cusped solitons of the Camassa–Holm equation. I. Cuspon solitary wave and antipeakon limit", Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 34 (3): 730–739, doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2007.01.033, Bibcode: 2007CSF....34..730P

- Parker, Allen (2008), "Wave dynamics for peaked solitons of the Camassa–Holm equation", Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 35 (2): 220–237, doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2007.07.049, Bibcode: 2008CSF....35..220P

- Qiao, Zhijun (2003), "The Camassa–Holm hierarchy, N-dimensional integrable systems, and algebro-geometric solution on a symplectic submanifold", Communications in Mathematical Physics 239 (1–2): 309–341, doi:10.1007/s00220-003-0880-y, Bibcode: 2003CMaPh.239..309Q

- Reyes, Enrique G. (2002), "Geometric integrability of the Camassa–Holm equation", Lett. Math. Phys. 59 (2): 117–131, doi:10.1023/A:1014933316169

- Rodríguez-Blanco, Guillermo (2001), "On the Cauchy problem for the Camassa–Holm equation", Nonlinear Analysis 46 (3): 309–327, doi:10.1016/S0362-546X(01)00791-X

- Schiff, Jeremy (1998), "The Camassa–Holm equation: a loop group approach", Physica D 121 (1–2): 24–43, doi:10.1016/S0167-2789(98)00099-2, Bibcode: 1998PhyD..121...24S

- Vaninsky, K. L. (2005), "Equations of Camassa–Holm type and Jacobi ellipsoidal coordinates", Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 58 (9): 1149–1187, doi:10.1002/cpa.20089

- Wahlén, Erik (2005), "A blow-up result for the periodic Camassa–Holm equation", Archiv der Mathematik 84 (4): 334–340, doi:10.1007/s00013-004-1199-4

- Wahlén, Erik (2006), "Global existence of weak solutions to the Camassa–Holm equation", Int. Math. Res. Not. 2006: 28976, doi:10.1155/IMRN/2006/28976

- Wu, Shuyin; Yin, Zhaoyang (2006), "Blow-up, blow-up rate and decay of the solution of the weakly dissipative Camassa–Holm equation", J. Math. Phys. 47 (1): 013504, 12 pp, doi:10.1063/1.2158437, Bibcode: 2006JMP....47a3504W

- Xin, Zhouping; Zhang, Ping (2002), "On the uniqueness and large time behavior of the weak solutions to a shallow water equation", Comm. Partial Differential Equations 27 (9–10): 1815–1844, doi:10.1081/PDE-120016129

- Zampogni, Luca (2007), "On algebro-geometric solutions of the Camassa–Holm hierarchy", Adv. Nonlinear Stud. 7 (3): 345–380, doi:10.1515/ans-2007-0303

|