Chemistry:Epoxidation of allylic alcohols

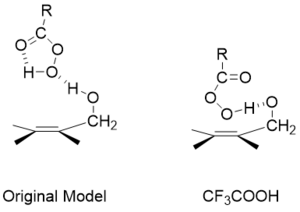

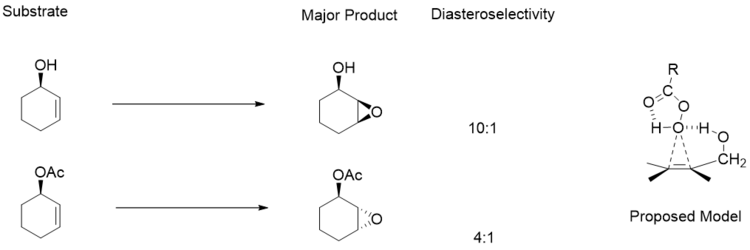

The epoxidation of allylic alcohols is a class of epoxidation reactions in organic chemistry. One implementation of this reaction is the Sharpless epoxidation. Early work showed that allylic alcohols give facial selectivity when using meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (m-CPBA) as an oxidant. This selectivity was reversed when the allylic alcohol was acetylated. This finding leads to the conclusion that hydrogen bonding played a key role in selectivity and the following model was proposed.[1]

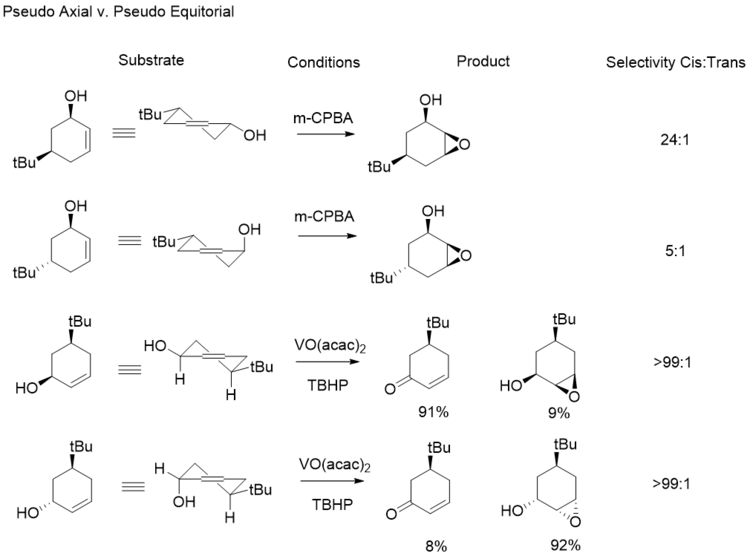

For cyclic allylic alcohols, greater selectivity is seen when the alcohol is locked in the pseudo equatorial position rather than the pseudo axial position.[2] However, it was found that for metal catalyzed systems such as those based on vanadium, reaction rates were accelerated when the hydroxyl group was in the axial position by a factor of 34. Substrates which were locked in the pseudo equatorial position were shown to undergo oxidation to form the ene-one. In both cases of vanadium catalyzed epoxidations, the epoxidized product showed excellent selectivity for the syn diastereomer.[3]

In the absence of hydrogen bonding, steric effects direct peroxide addition to the opposite face. However, perfluoric peracids are still able to hydrogen bond with protected alcohols and give normal selectivity with the hydrogen present on the peracid.[4]

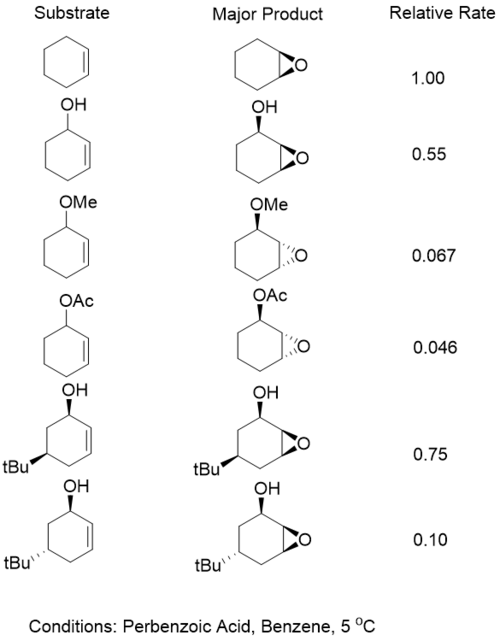

Although the presence of an allylic alcohol does lead to increased stereoselectivity, the rates of these reactions are slower than systems lacking alcohols. However, the reaction rates of substrates with a hydrogen bonding group are still faster than the equivalent protected substrates. This observation is attributed to a balance of two factors. The first is the stabilization of the transition state as a result of the hydrogen bonding. The second is the electron-withdrawing nature of the oxygen, which draws electron density away from the alkene, lowering its reactivity.[5]

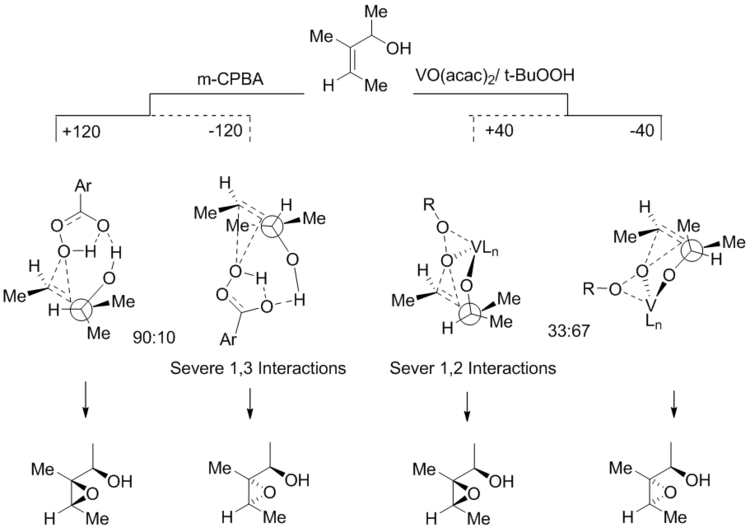

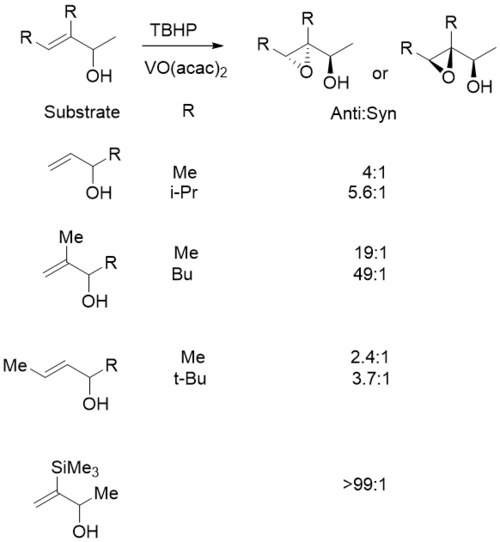

Acyclic allylic alcohols exhibit good selectivity as well. In these systems both A1,2 (steric interactions with vinyl) and A1,3 strain are considered. It has been shown that a dihedral angle of 120 best directs substrates which hydrogen bond with the directing group. This geometry allows for the peroxide to be properly positioned, as well as to allow minimal donation from the C-C pi into the C-O sigma star.[6] This donation would lower the electron density of the alkene, and deactivate the reaction. However, vanadium complexes do not hydrogen bond with their substrates. Instead they coordinate with the alcohol. This means that a dihedral angle of 40 allows for ideal position of the peroxide sigma star orbital.[7]

In systems that hydrogen bond, A1,3 strain plays a larger role because the required geometry forces any allylic substituents to have severe A1,3 interactions, but avoids A1,2. This leads to syn addition of the resulting epoxide. In the vanadium case, the required geometry leads to severe A1,2 interactions, but avoids A1,3, leading to formation of the epoxide anti to the directing group. Vanadium catalyzed epoxidations have been shown to be very sensitive to the steric bulk of the vinyl group.[8][9][10]

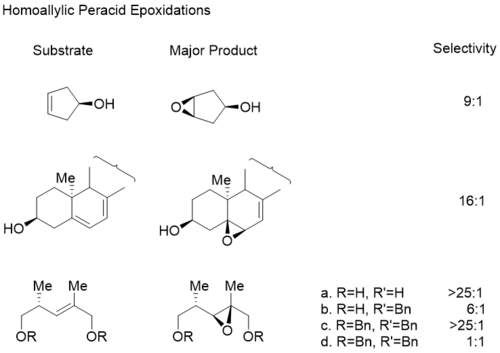

Homoallylic alcohols are effective directing groups for epoxidations in both cyclic and acyclic systems for substrates which show hydrogen bonding. However these reactions tend to have lower levels of selectivity.[11][12]

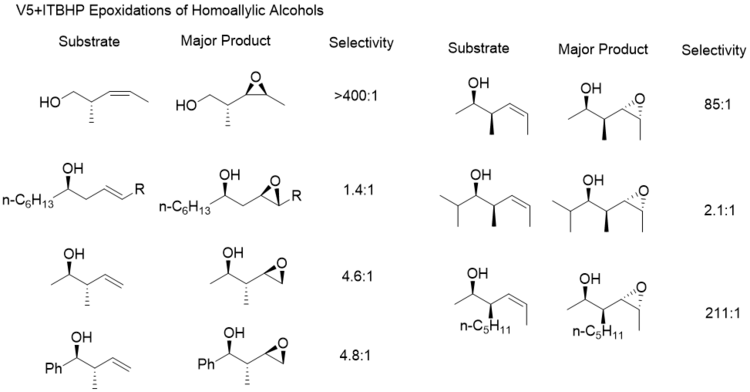

While hydrogen bonding substrates give the same type of selectivity in allylic and homoallylic cases, the opposite is true of vanadium catalysts.

A transition state proposed by Mihelich shows that for these reactions, the driving force for selectivity is minimizing A1,3 strain in a pseudo chair structure.

The proposed transition state shows that the substrate will try to assume a conformation which minimizes the allyic strain. To do this, the least sterically bulky R group will rotate to assume the R4 position.[13]

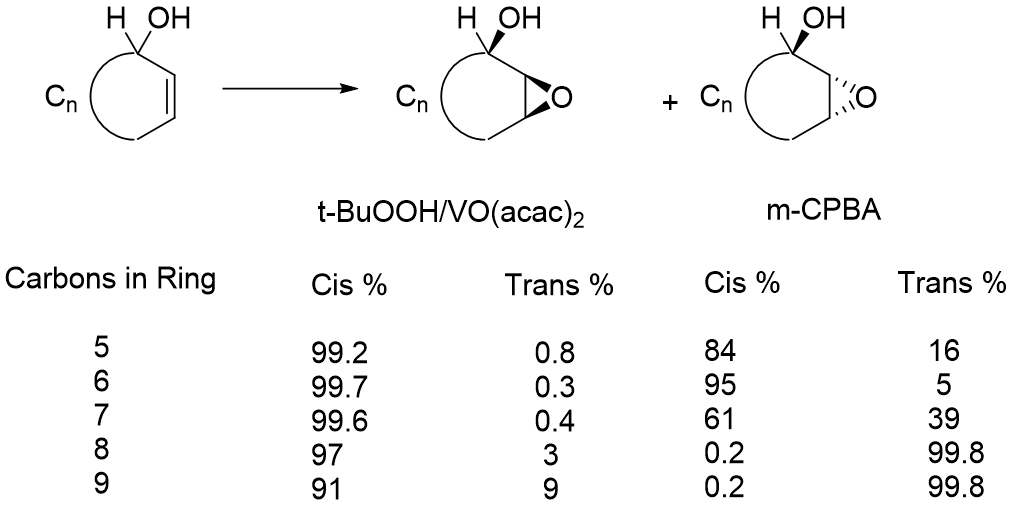

Although peracids and metal catalyzed epoxidations show different selectivity in acyclic systems, they show relatively similar selectivity in cyclic systems For cyclic ring systems that are smaller seven or smaller or 10 or lager, similar patterns of selectivity are observed. However it has been shown that for medium-sized rings (eight and nine) peracid oxidizers show reverse selectivity, while vanadium catalyzed reactions continue to show formation of the syn epoxide.[14]

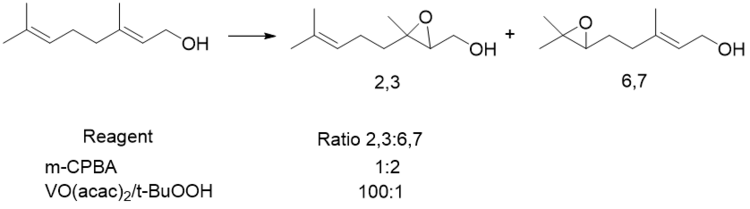

Although it is the least reactive metal catalyst for epoxidations, vanadium is highly selective for alkenes with allylic alcohols. Early work done by Sharpless shows its preference for reacting with alkenes with allylic alcohols over more substituted electron dense alkenes. In this case, Vanadium showed reverse regioselectivity from both m-CPBA and the more reactive molybdenum species. Although vanadium is generally less reactive than other metal complexes, in the presence of allylic alcohols, the rate of the reaction is accelerated beyond that of molybdenum, the most reactive metal for epoxidations.[15]

References

- ↑ Henbest, H. B.; Wilson, R. A. L. (1957). "376. Aspects of stereochemistry. Part I. Stereospecificity in formation of epoxides from cyclic allylic alcohols". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 1958. doi:10.1039/JR9570001958.

- ↑ Chamberlain, P.; Roberts, M. L.; Whitham, G. H. (1970). "Epoxidation of allylic alcohols with peroxy-acids. Attempts to define transition state geometry". Journal of the Chemical Society B: Physical Organic: 1374. doi:10.1039/J29700001374.

- ↑ Weyerstahl, Peter; Marschall-Weyerstahl, Helga; Penninger, Josef; Walther, Lutz (1987). "Terpenes and terpene derivatives-22". Tetrahedron 43 (22): 5287–5298. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)87705-X.

- ↑ McKittrick, Brian A.; Ganem, Bruce (1985). "Syn-stereoselective epoxidation of allylic ethers using CF3CO3H". Tetrahedron Letters 26 (40): 4895–4898. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)94979-7.

- ↑ Hoveyda, Amir H.; Evans, David A.; Fu, Gregory C. (1993). "Substrate-directable chemical reactions". Chemical Reviews 93 (4): 1307–1370. doi:10.1021/cr00020a002.

- ↑ Houk, K. N.; Paddon-Row, M. N.; Rondan, N. G.; Wu, Y. D.; Brown, F. K.; Spellmeyer, D. C.; Metz, J. T.; Li, Y .; Loncharich, R. J. Science, 1986, 231, 1108-1117.

- ↑ Waldemar, A.; Wirth, T. Accounts of Chemical Research, 1999, 32.8, 703-710.

- ↑ Mihelich, Edward D. (1979). "Vanadium-catalyzed epoxidations. I. A new selectivity pattern for acyclic allylic alcohols". Tetrahedron Letters 20 (49): 4729–4732. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)86695-8.

- ↑ Rossiter, B.E.; Verhoeven, T.R.; Sharpless, K.B. (1979). "Stereoselective epoxidation of acyclic allylic alcohols. A correction of our previous work". Tetrahedron Letters 20 (49): 4733–4736. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)86696-X.

- ↑ Narula, Acharan S. (1982). "Stereoselective introduction of chiral centres in acyclic precursors: A probe into the transition state for V5+-catalyzed t-butylhydroperoxide (TBHP) epoxidation of acyclic allylic alcohols and its synthetic implications". Tetrahedron Letters 23 (52): 5579–5582. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)85899-2.

- ↑ Cragg, G. M. L.; Meakins, G. D. (1965). "366. Steroids of unnatural configuration. Part IX. Oxidation of 9α-lumisterol (pyrocalciferol) and 9β-ergosterol (isopyrocalciferol) with perbenzoic acid". J. Chem. Soc.: 2054–2063. doi:10.1039/JR9650002054.

- ↑ Johnson, M. R.; Kishi, Y. Tetrahedron Lett., 1979, 4347-4350.

- ↑ Mihelich, Edward D.; Daniels, Karen; Eickhoff, David J. (1981). "Vanadium-catalyzed epoxidations. 2. Highly stereoselective epoxidations of acyclic homoallylic alcohols predicted by a detailed transition-state model". Journal of the American Chemical Society 103 (25): 7690–7692. doi:10.1021/ja00415a067.

- ↑ Itoh, Takashi; Jitsukawa, Koichiro; Kaneda, Kiyotomi; Teranishi, Shiichiro (1979). "Vanadium-catalyzed epoxidation of cyclic allylic alcohols. Stereoselectivity and stereocontrol mechanism". Journal of the American Chemical Society 101: 159–169. doi:10.1021/ja00495a027.

- ↑ Sharpless, K. B.; Michaelson, R. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1973, 95 (18)

|