Dihedral angle

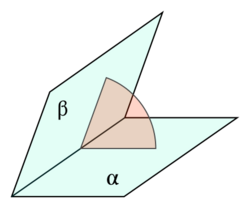

A dihedral angle is the angle between two intersecting planes or half-planes. In chemistry, it is the clockwise angle between half-planes through two sets of three atoms, having two atoms in common. In solid geometry, it is defined as the union of a line and two half-planes that have this line as a common edge. In higher dimensions, a dihedral angle represents the angle between two hyperplanes. The planes of a flying machine are said to be at positive dihedral angle when both starboard and port main planes (commonly called "wings") are upwardly inclined to the lateral axis; when downwardly inclined they are said to be at a negative dihedral angle.

Mathematical background

When the two intersecting planes are described in terms of Cartesian coordinates by the two equations

the dihedral angle, between them is given by:

and satisfies It can easily be observed that the angle is independent of and .

Alternatively, if nA and nB are normal vector to the planes, one has

where nA · nB is the dot product of the vectors and |nA| |nB| is the product of their lengths.[1]

The absolute value is required in above formulas, as the planes are not changed when changing all coefficient signs in one equation, or replacing one normal vector by its opposite.

However the absolute values can be and should be avoided when considering the dihedral angle of two half planes whose boundaries are the same line. In this case, the half planes can be described by a point P of their intersection, and three vectors b0, b1 and b2 such that P + b0, P + b1 and P + b2 belong respectively to the intersection line, the first half plane, and the second half plane. The dihedral angle of these two half planes is defined by

- ,

and satisfies In this case, switching the two half-planes gives the same result, and so does replacing with In chemistry (see below), we define a dihedral angle such that replacing with changes the sign of the angle, which can be between −π and π.

In polymer physics

In some scientific areas such as polymer physics, one may consider a chain of points and links between consecutive points. If the points are sequentially numbered and located at positions r1, r2, r3, etc. then bond vectors are defined by u1=r2−r1, u2=r3−r2, and ui=ri+1−ri, more generally.[2] This is the case for kinematic chains or amino acids in a protein structure. In these cases, one is often interested in the half-planes defined by three consecutive points, and the dihedral angle between two consecutive such half-planes. If u1, u2 and u3 are three consecutive bond vectors, the intersection of the half-planes is oriented, which allows defining a dihedral angle that belongs to the interval (−π, π]. This dihedral angle is defined by[3]

or, using the function atan2,

This dihedral angle does not depend on the orientation of the chain (order in which the point are considered) — reversing this ordering consists of replacing each vector by its opposite vector, and exchanging the indices 1 and 3. Both operations do not change the cosine, but change the sign of the sine. Thus, together, they do not change the angle.

A simpler formula for the same dihedral angle is the following (the proof is given below)

or equivalently,

This can be deduced from previous formulas by using the vector quadruple product formula, and the fact that a scalar triple product is zero if it contains twice the same vector:

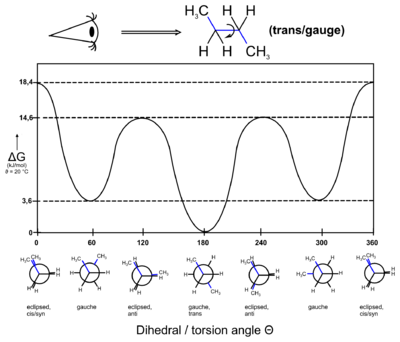

Given the definition of the cross product, this means that is the angle in the clockwise direction of the fourth atom compared to the first atom, while looking down the axis from the second atom to the third. Special cases (one may say the usual cases) are , and , which are called the trans, gauche+, and gauche− conformations.

In stereochemistry

|

|

|

| Configuration names according to dihedral angle |

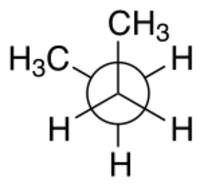

syn n-Butane in the gauche− conformation (−60°) Newman projection |

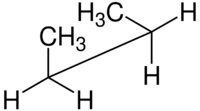

syn n-Butane sawhorse projection |

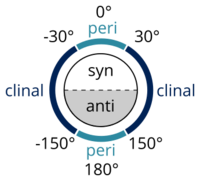

In stereochemistry, a torsion angle is defined as a particular example of a dihedral angle, describing the geometric relation of two parts of a molecule joined by a chemical bond.[4][5] Every set of three non-colinear atoms of a molecule defines a half-plane. As explained above, when two such half-planes intersect (i.e., a set of four consecutively-bonded atoms), the angle between them is a dihedral angle. Dihedral angles are used to specify the molecular conformation.[6] Stereochemical arrangements corresponding to angles between 0° and ±90° are called syn (s), those corresponding to angles between ±90° and 180° anti (a). Similarly, arrangements corresponding to angles between 30° and 150° or between −30° and −150° are called clinal (c) and those between 0° and ±30° or ±150° and 180° are called periplanar (p).

The two types of terms can be combined so as to define four ranges of angle; 0° to ±30° synperiplanar (sp); 30° to 90° and −30° to −90° synclinal (sc); 90° to 150° and −90° to −150° anticlinal (ac); ±150° to 180° antiperiplanar (ap). The synperiplanar conformation is also known as the syn- or cis-conformation; antiperiplanar as anti or trans; and synclinal as gauche or skew.

For example, with n-butane two planes can be specified in terms of the two central carbon atoms and either of the methyl carbon atoms. The syn-conformation shown above, with a dihedral angle of 60° is less stable than the anti-conformation with a dihedral angle of 180°.

For macromolecular usage the symbols T, C, G+, G−, A+ and A− are recommended (ap, sp, +sc, −sc, +ac and −ac respectively).

Proteins

A Ramachandran plot (also known as a Ramachandran diagram or a [φ,ψ] plot), originally developed in 1963 by G. N. Ramachandran, C. Ramakrishnan, and V. Sasisekharan,[7] is a way to visualize energetically allowed regions for backbone dihedral angles ψ against φ of amino acid residues in protein structure. In a protein chain three dihedral angles are defined:

- ω (omega) is the angle in the chain Cα − C' − N − Cα,

- φ (phi) is the angle in the chain C' − N − Cα − C'

- ψ (psi) is the angle in the chain N − Cα − C' − N (called φ′ by Ramachandran)

The figure at right illustrates the location of each of these angles (but it does not show correctly the way they are defined).[8]

The planarity of the peptide bond usually restricts ω to be 180° (the typical trans case) or 0° (the rare cis case). The distance between the Cα atoms in the trans and cis isomers is approximately 3.8 and 2.9 Å, respectively. The vast majority of the peptide bonds in proteins are trans, though the peptide bond to the nitrogen of proline has an increased prevalence of cis compared to other amino-acid pairs.[9]

The side chain dihedral angles are designated with χn (chi-n).[10] They tend to cluster near 180°, 60°, and −60°, which are called the trans, gauche−, and gauche+ conformations. The stability of certain sidechain dihedral angles is affected by the values φ and ψ.[11] For instance, there are direct steric interactions between the Cγ of the side chain in the gauche+ rotamer and the backbone nitrogen of the next residue when ψ is near -60°.[12] This is evident from statistical distributions in backbone-dependent rotamer libraries.

Converting from dihedral angles to Cartesian coordinates in chains

It is common to represent polymers backbones, notably proteins, in internal coordinates; that is, a list of consecutive dihedral angles and bond lengths. However, some types of computational chemistry instead use cartesian coordinates. In computational structure optimization, some programs need to flip back and forth between these representations during their iterations. This task can dominate the calculation time. For processes with many iterations or with long chains, it can also introduce cumulative numerical inaccuracy. While all conversion algorithms produce mathematically identical results, they differ in speed and numerical accuracy.[13][non-primary source needed]

Geometry

Every polyhedron has a dihedral angle at every edge describing the relationship of the two faces that share that edge. This dihedral angle, also called the face angle, is measured as the internal angle with respect to the polyhedron. An angle of 0° means the face normal vectors are antiparallel and the faces overlap each other, which implies that it is part of a degenerate polyhedron. An angle of 180° means the faces are parallel, as in a tiling. An angle greater than 180° exists on concave portions of a polyhedron.

Every dihedral angle in an edge-transitive polyhedron has the same value. This includes the 5 Platonic solids, the 13 Catalan solids, the 4 Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra, the two quasiregular solids, and two quasiregular dual solids.

Law of cosines for dihedral angle

Given 3 faces of a polyhedron which meet at a common vertex P and have edges AP, BP and CP, the cosine of the dihedral angle between the faces containing APC and BPC is:[14]

This can be deduced from Spherical law of cosines

See also

References

- ↑ "Angle Between Two Planes". https://math.tutorvista.com/geometry/angle-between-two-planes.html.

- ↑ Kröger, Martin (2005). Models for polymeric and anisotropic liquids. Springer. ISBN 3540262105.

- ↑ Blondel, Arnaud; Karplus, Martin (7 Dec 1998). "New formulation for derivatives of torsion angles and improper torsion angles in molecular mechanics: Elimination of singularities". Journal of Computational Chemistry 17 (9): 1132–1141. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19960715)17:9<1132::AID-JCC5>3.0.CO;2-T.

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Torsion angle". doi:10.1351/goldbook.T06406

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Dihedral angle". doi:10.1351/goldbook.D01730

- ↑ Anslyn, Eric; Dennis Dougherty (2006). Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. University Science. p. 95. ISBN 978-1891389313.

- ↑ Ramachandran, G. N.; Ramakrishnan, C.; Sasisekharan, V. (1963). "Stereochemistry of polypeptide chain configurations". Journal of Molecular Biology 7: 95–9. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(63)80023-6. PMID 13990617.

- ↑ Richardson, J. S. (1981). "The Anatomy and Taxonomy of Protein Structure". Anatomy and Taxonomy of Protein Structures. Advances in Protein Chemistry. 34. pp. 167–339. doi:10.1016/S0065-3233(08)60520-3. ISBN 9780120342341.

- ↑ "Detecting Proline and Non-Proline Cis Isomers in Protein Structures from Sequences Using Deep Residual Ensemble Learning". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 58 (9): 2033–2042. August 2018. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00442. PMID 30118602.

- ↑ "Side Chain Conformation". http://www.cryst.bbk.ac.uk/PPS95/course/3_geometry/conform.html.

- ↑ Dunbrack, RL Jr.; Karplus, M (20 March 1993). "Backbone-dependent rotamer library for proteins. Application to side-chain prediction.". Journal of Molecular Biology 230 (2): 543–74. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1993.1170. PMID 8464064.

- ↑ Dunbrack, RL Jr; Karplus, M (May 1994). "Conformational analysis of the backbone-dependent rotamer preferences of protein sidechains.". Nature Structural Biology 1 (5): 334–40. doi:10.1038/nsb0594-334. PMID 7664040.

- ↑ Parsons, J.; Holmes, J. B.; Rojas, J. M.; Tsai, J.; Strauss, C. E. (2005), "Practical conversion from torsion space to cartesian space for in silico protein synthesis", Journal of Computational Chemistry 26 (10): 1063–1068, doi:10.1002/jcc.20237, PMID 15898109

- ↑ "dihedral angle calculator polyhedron". http://www.had2know.com/academics/dihedral-angle-calculator-polyhedron.html.

External links

- The Dihedral Angle in Woodworking at Tips.FM

- Analysis of the 5 Regular Polyhedra gives a step-by-step derivation of these exact values.

|