Chemistry:Herkimer diamond

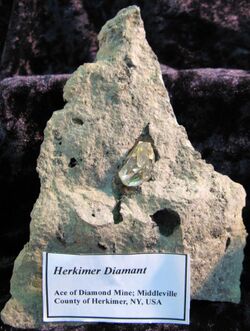

Herkimer diamonds are double-terminated quartz crystals discovered within exposed outcrops of dolomite in and around Herkimer County, New York, and the Mohawk River Valley in the US.[1][2] They are not diamonds; the "diamond" in their name is due to both their clarity and well formed faces. Because the first discovery sites were in the village of Middleville and in the city of Little Falls, respectively, the crystal is also known as a Middleville diamond or a Little Falls diamond.[3]

Herkimer diamonds became widely recognized after workmen discovered them in large quantities while cutting into the Mohawk River Valley dolomite in the late 18th century. Geologists discovered exposed dolomite in Herkimer County outcroppings and began mining there, leading to the "Herkimer diamond" moniker. Double-terminated quartz crystals may be found in sites around the world, but only those mined in Herkimer County can be given this name.

Process of formation

The geologic history of these crystals began about 500 million years ago in a shallow sea which was receiving sediments from the ancient Adirondack Mountains to the north. The calcium and magnesium carbonate sediments accumulated and lithified to form the dolomite bedrock currently known as the Little Falls Formation and formerly as the Little Falls Dolostone.[4] While buried, cavities were formed by acidic waters forming the vugs in which the quartz crystals formed. While the dolomite unit is Cambrian in age, the quartz within the vugs is interpreted to have formed during the Carboniferous Period.[5] Waxy organic material, silicon dioxide and pyrite (iron sulfide) was present as minor constituents of rock made of dolomite and calcite. As sediment buried the rock and temperatures rose, crystals grew in the cavities very slowly, resulting in quartz crystals of exceptional clarity. Inclusions can be found in these crystals that provide clues to the origins of the Herkimer diamonds. Found within the inclusions are solids, liquids (salt water or petroleum), gases (most often carbon dioxide), two- and three-phase inclusions, and negative (uniaxial) crystals. A black hydrocarbon is the most common solid inclusion.[6]

See also

- Cape May diamonds, another form of quartz referred to as "diamonds"

References

- ↑ King, Hobart M.. "Herkimer Diamonds". Geology.com. http://geology.com/articles/herkimer-diamonds.shtml.

- ↑ Pough, Frederick (1960). A Field Guide to Rocks and Minerals. p. 232.

- ↑ ""Herkimer-style" Quartz". Mindat. http://www.mindat.org/min-1877.html.

- ↑ Baldwin, Mike (2003-07-11). "Herkimer Diamonds". MAGS Explorer 2 (7). http://www.memphisgeology.org/images/Explorer0703.pdf. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- ↑ Muskatt, H.S.; Tollerton, V.P., Jr. (September 18–20, 1992). "Field trip guidebook". in April, R.H.. New York State Geological Association Guidebook, annual meeting. Hamilton, NY., as quoted in GEOLEX, USGS

- ↑ "Hydrocarbon". Herkimer History. https://www.herkimerhistory.com/Hydrocarbon.html.

External links

- Website for the New York State Academy of Mineralogy

- Prospecting for Herkimer Diamonds

- HerkimerHistory.com

- Video of mining for Herkimer Diamonds with a jackhammer

- Book Review: Collector’s Guide to Herkimer Diamonds

|