Chemistry:Nomenclature of monoclonal antibodies

| Prefix | Target substem | Stem | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| meaning | meaning | |||

| variable | -ami- | serum amyloid protein (SAP)/amyloidosis (pre-substem) |

-bart | artificial antibody |

| -ba- | bacterial | -ment | fragment (derived from a variable domain) | |

| -ci- | cardiovascular | -mig | multi-immunoglobulin (e.g. BsMAb) | |

| -de- | metabolic or endocrine pathways | -tug | unmodified immunoglobulin | |

| -eni- | enzyme inhibition | |||

| -fung- | fungal | |||

| -gro- | skeletal muscle mass related growth

factors and receptors (pre-substem) | |||

| -ki- | cytokine and cytokine receptor | |||

| -ler- | allergen | |||

| -ne- | neural | |||

| -os- | bone | |||

| -pru- | immunosuppressive | |||

| -sto- | immunostimulatory | |||

| -ta- | tumor | |||

| -toxa- | toxin | |||

| -vet- | veterinary use (sub-stem) | |||

| -vi- | viral | |||

The nomenclature of monoclonal antibodies is a naming scheme for assigning generic, or nonproprietary, names to monoclonal antibodies. An antibody is a protein that is produced in B cells and used by the immune system of humans and other vertebrate animals to identify a specific foreign object like a bacterium or a virus. Monoclonal antibodies are those that were produced in identical cells, often artificially, and so share the same target object. They have a wide range of applications including medical uses.[5]

This naming scheme is used for both the World Health Organization's International Nonproprietary Names (INN)[6] and the United States Adopted Names (USAN)[7] for pharmaceuticals. In general, word stems are used to identify classes of drugs, in most cases placed word-finally. All monoclonal antibody names assigned until 2021 end with the stem -mab; newer names have different stems. Unlike most other pharmaceuticals, monoclonal antibody nomenclature uses different preceding word parts (morphemes) depending on structure and function. These are officially called substems and sometimes erroneously infixes, even by the USAN Council itself.[7]

The scheme has been revised several times: in 2009, in 2017, in 2021, and in 2022.[1][2][8][4]

Components

Stem

Until 2021, the stem -mab was used for all monoclonal antibodies as well as for their fragments, as long as at least one variable domain (the domain that contains the target binding structure) was included.[9] This is the case for antigen-binding fragments[10] and single-chain variable fragments,[11] among other artificial proteins.

The new scheme, published in November 2021, divides antibodies into four groups: Group 1 uses the stem -tug for full-length unmodified immunoglobulins, those that might occur as such in the immune system. Group 2 has the stem -bart for full-length antibodies artificial, which contain one or more engineered regions (at least one point mutation). Group 3 uses -mig for multi-immunoglobulins of any length, comprising bispecific and multispecific monoclonal antibodies. Finally, group 4 assigns the stem -ment for monospecific antibody fragments without an Fc region.[1][2]

Other antibody parts (such as Fc regions) and antibody mimetics use different naming schemes.

Substem for source

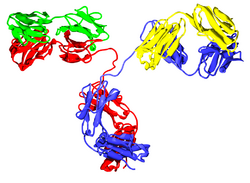

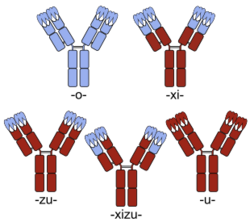

Human parts are shown in brown, non-human parts in blue. The variable domains are the boxes on top of each antibody; the CDRs within these domains are represented as triple loops.

For antibodies named until early 2017, the substem preceding the stem denotes the animal from which the antibody was obtained.[7] The first monoclonal antibodies were produced in mice (substem -o-, yielding the ending -omab; usually Mus musculus, the house mouse) or other non-human organisms. Neither INN nor USAN has ever been requested for antibodies from rats (theoretically -a-), hamsters (-e-) and primates (-i-).[9]

These non-human antibodies are recognized as foreign by the human immune system and may be rapidly cleared from the body, provoke an allergic reaction, or both.[12][13] To avoid this, parts of the antibody can be replaced with human amino acid sequences, or pure human antibodies can be engineered. If the constant region is replaced with the human form, the antibody is termed chimeric and the substem used was -xi-. Part of the variable regions may also be substituted, in which case it is called humanized and -zu- was used; typically, everything is replaced except the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs), the three loops of amino acid sequences at the outside of each variable region that bind to the target structure; although some other residues may have to remain non-human in order to achieve good binding. Partly chimeric and partly humanized antibodies used -xizu-. These three substems did not indicate the foreign species used for production. Thus, the human/mouse chimeric antibody basiliximab ends in -ximab just as does the human/macaque antibody gomiliximab. Purely human antibodies used -u-.[3]

Rat/mouse hybrid antibodies can be engineered with binding sites for two different antigens. These drugs, termed trifunctional antibodies, had the substem -axo-.[14]

Newer antibody names omit this part of the name.[8]

Substem for target

The substem preceding the source of the antibody refers to the medicine's target. Examples of targets are tumors, organ systems like the circulatory system, or infectious agents like bacteria or viruses. The term target does not imply what sort of action the antibody exerts. Therapeutic, prophylactic and diagnostic agents are not distinguished by this nomenclature.

In the naming scheme as originally developed, these substems mostly consist of a consonant, a vowel, then another consonant. The final letter may be dropped if the resulting name would be difficult to pronounce otherwise. Examples include -ci(r)- for the circulatory system, -li(m)- for the immune system (lim stands for lymphocyte) and -ne(r)- for the nervous system. The final letter is usually omitted if the following source substem begins with a consonant (such as -zu- or -xi-), but not all target substems are used in their shortened form. -mul-, for example, is never reduced to -mu- because no chimeric or humanized antibodies targeting the musculoskeletal system ever received an INN. Combination of target and source substems resulted in endings like -limumab (immune system, human) or -ciximab (circulatory system, chimeric, consonant r dropped).[7]

New and shorter target substems were adopted in 2009. They mostly consist of a consonant, plus a vowel which is omitted if the source substem begins with a vowel. For example, human antibodies targeting the immune system receive names ending in -lumab instead of the old -limumab. Some endings like -ciximab remained unchanged.[3] The old system employed seven different substems for tumor targets, depending on the type of tumor. Because many antibodies are investigated for several tumor types, the new convention only has -t(u)-.[7]

With the source substem being discontinued in 2017, the need for dropping the target substem's final vowel disappeared.[8]

Prefix

The prefix carries no special meaning. It should be unique for each medicine and contribute to a well-sounding name.[3] This means that antibodies with the same source and target substems are only distinguished by their prefix. Even antibodies targeting exactly the same structure are differently prefixed, such as the adalimumab and golimumab, both of which are TNF inhibitors but differ in their chemical structure.[15][16]

Additional words

A second word following the name of the antibody indicates that another substance is attached,[3] which is done for several reasons.

- An antibody can be PEGylated (attached to molecules of polyethylene glycol) to slow down its degradation by enzymes and to decrease its immunogenicity;[17] this is shown by the word pegol as in alacizumab pegol.[18]

- A cytotoxic agent can be linked to an anti-tumor antibody for drug targeting purposes. The word vedotin, for example, stands for monomethyl auristatin E which is toxic by itself but predominantly affects cancer cells if used in conjugates like glembatumumab vedotin.[19]

- A chelator for binding a radioisotope can be attached. Pendetide, a derivative of pentetic acid, is used for example in capromab pendetide to chelate indium-111.[20] If the drug contains a radioisotope, the name of the isotope precedes the name of the antibody.[3] Consequently, indium (111In) capromab pendetide is the name for the above example including indium-111.[20]

Overview

| Prefix | Target substem | Source substem (until 2017) | Stem | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~1993 | 2009–2017 | 2017–2021 | from 2021 | meaning | meaning | old | from 2021 | meaning | |||

| variable | — | -ami- | -ami- | -ami- | serum amyloid protein (SAP)/amyloidosis (pre-substem) |

-a- | rat | -mab | -bart | artificial antibody | |

| -anibi- | — | — | — | angiogenesis (inhibitor) | -e- | hamster | -ment | fragment (derived from a variable domain) | |||

| -ba(c)- | -b(a)- | -ba- | -ba- | bacterial | -i- | primate | -mig | multi-immunoglobulin (e.g. BsMAb) | |||

| -ci(r)- | -c(i)- | -ci- | -ci- | cardiovascular | -o- | mouse | -tug | unmodified immunoglobulin | |||

| -d(e)- | -d(e)-[lower-alpha 1] | -de-[lower-alpha 1] | -de- | endocrine | -u- | human | |||||

| — | — | -eni-[lower-alpha 2] | -eni- | enzyme inhibition | -xi- | chimeric (human/foreign) | |||||

| -fung- | -f(u)- | -fung- | -fung- | fungal | -zu- | humanized | |||||

| -gr(o)- | -gros- | -gros- | -gro-[lower-alpha 3] | skeletal muscle mass related growth factors and receptors (pre-substem) |

-xizu- | chimeric/humanized hybrid | |||||

| -ki(n)- | -k(i)- | -ki- | -ki- | formerly: interleukin; from 2020: cytokine and cytokine receptor | -axo- | rat/mouse hybrid (see trifunctional antibody) | |||||

| -les- | — | — | — | inflammatory lesions[25] | |||||||

| -li(m)- | -l(i)- | -li- | -ler- | immunomodulating | allergen | -vet- | veterinary use (pre-substem)[lower-alpha 4] | ||||

| -pru- | immunosuppressive | ||||||||||

| -sto- | immunostimulatory | ||||||||||

| -mul- | — | — | — | musculoskeletal system[26] | |||||||

| -ne(u)(r)- | -n(e)- | -ne- | -ne- | neural (nervous system) | |||||||

| -os- | -s(o)- | -os- | -os- | bone | |||||||

| -co(l)- | -t(u)- | -ta- | -ta- | colonic tumor | tumor | ||||||

| -go(t)- | testicular tumor | ||||||||||

| -go(v)- | ovarian tumor | ||||||||||

| -ma(r)- | mammary tumor | ||||||||||

| -me(l)- | melanoma | ||||||||||

| -pr(o)- | prostate tumor | ||||||||||

| -tu(m)- | miscellaneous tumor | ||||||||||

| -toxa- | -tox(a)- | -toxa- | -toxa- | toxin | |||||||

| — | — | -vet- | -vet- | veterinary use (pre-stem)[lower-alpha 4] | |||||||

| -vi(r)- | -v(i)- | -vi- | -vi- | viral | |||||||

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 not mentioned in documents of the 2010s

- ↑ introduced between 2017 and 2021

- ↑ changed in 2019 from -gros- to -gro- to avoid naming conflicts with -os-

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 can be inserted between target substem and stem, as in lo-ki-vet-mab (This part of the name was originally listed under the source substems and moved to the target substems when the former were dropped in 2017.[8])

History

Emil von Behring and Kitasato Shibasaburō discovered in 1890 that diphtheria and tetanus toxins were neutralized in the bloodstream of animals by substances they called antitoxins, which were specific for the respective toxin.[27] Behring received the first Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their find in 1901.[28] A year after the discovery, Paul Ehrlich used the term antibodies (German Antikörper) for these antitoxins.[29]

The principle of monoclonal antibody production, called hybridoma technology, was published in 1975 by Georges Köhler and César Milstein,[30] who were awarded the 1984 Medicine Nobel Prize for their discovery together with Niels Kaj Jerne.[31] Muromonab-CD3 was the first monoclonal antibody to be approved for clinical use in humans, in 1986.[32]

The World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the system of International Nonproprietary Names in 1950, with the first INN list being published three years later. The stem -mab for monoclonal antibodies was proposed around 1990, and the current system with target and source substems was developed between 1991 and 1993. Due to the collaboration between the WHO and the United States Adopted Names Council, antibody USANs have the same structure and are largely identical to INNs. Until 2009, more than 170 monoclonal antibodies received names following this nomenclature.[9][33]

In October 2008, the WHO convoked a working group to revise the nomenclature of monoclonal antibodies, to meet challenges discussed in April the same year. This led to the adoption of the new target substems in November 2009.[9] In spring 2010, the first new antibody names were adopted.[34]

In April 2017, at the WHO's 64th Consultation on International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances, it was decided to drop the source substem and from that meeting onwards, it is no longer used in new antibody names.[35] The revised nomenclature was published in May 2017.[23] The difficulty in capturing the complexity and subtleties of the many methods by which antibody drugs can be produced is one of the reasons that the INN dropped the source substem, as is the need for creating more clearly distinguishable names.[36][23]

The 2021 revision, published in November 2021, replaced the hitherto universal stem -mab with four distinct stems depending on the basic structure. Also, the target substem -li- for immunomodulating antibodies was split into substems for immunosuppressive (-pru-) and immunostimulatory antibodies (-sto-) and those targeting allergens (-ler-).[1][4]

Examples

1980s

- The monoclonal antibody muromonab-CD3, approved for clinical use in 1986, was named before these conventions took effect, and consequently its name does not follow them. Instead, it is a contraction from "murine monoclonal antibody targeting CD3".[32]

Convention until 2009

- Adalimumab is a drug targeting TNF alpha. Its name can be broken down into ada-lim-u-mab. Therefore, the drug is a human monoclonal antibody targeting the immune system. If adalimumab had been named between 2009 and 2017, it would have been adalumab (ada-l

i-u-mab). After 2017, it would be adalimab (ada-li-mab).[15] - Abciximab is a commonly used medication to prevent platelets from clumping together. Broken down into ab-ci-xi-mab, its name shows the drug to be a chimeric monoclonal antibody used on the cardiovascular system. This and the following two names would look the same if the 2009 convention were applied.[37]

- The name of the breast cancer medication trastuzumab can be analyzed as tras-tu-zu-mab. Therefore, the drug is a humanized monoclonal antibody used against a tumor.[38]

- Alacizumab pegol is a PEGylated humanized antibody targeting the circulatory system.[18]

- Technetium (99mTc) pintumomab[39] and technetium (99mTc) nofetumomab merpentan are radiolabeled antibodies, merpentan being a chelator that links the antibody nofetumomab to the radioisotope technetium-99m.[40]

- Rozrolimupab is a polyclonal antibody. Broken down into rozro-lim-u-pab, its name shows the drug to be a human polyclonal antibody (-pab) acting on the immune system.[41]

Convention from 2009 to 2017

- Olaratumab is an antineoplastic. Its name is composed of the components olara-t-u-mab. This shows that the drug is a human monoclonal antibody acting against tumors.[34]

- The name of benralizumab, a drug designed for the treatment of asthma, has the components benra-li-zu-mab, marking it as a humanized antibody acting on the immune system.[42]

Convention from 2017 to 2021

- Belantamab mafodotin (belan-ta-mab) is also an antineoplastic. It is conjugated to a cytotoxic agent that is chemically related to monomethyl auristatin E.[43]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 World Health Organization (November 2021), New INN monoclonal antibody (mAb) nomenclature scheme: Geneva, November 2021, https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/international-nonproprietary-names-(inn)/new_mab_-nomenclature-_2021.pdf, retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 World Health Organization (2021-10-31), New INN monoclonal antibody (mAb) nomenclature scheme: International Nonproprietary Names scheme for monoclonal antibody (mAb), https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/inn-21-531, retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 "General policies for monoclonal antibodies". World Health Organization. 2009-12-18. https://www.who.int/medicines/services/inn/generalpoliciesmonoclonalantibodiesjan10.pdf.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "New INN monoclonal antibody (mAb) nomenclature scheme (May 2022)". 2 May 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/inn-22-542.

- ↑ Janeway, CA Jr.; Travers, P.; Walport, M.; Shlomchik, M. J. (2001). Immunobiology (5th ed.). Garland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8153-3642-6. https://archive.org/details/immunobiology00char.

- ↑ "Guidelines on the Use of International Nonproprietary Names (INNs) for Pharmaceutical Substances". 1997. pp. 27–28. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1997/WHO_PHARM_S_NOM_1570.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 "AMA (USAN) Monoclonal antibodies". United States Adopted Names. 2007-08-07. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-science/united-states-adopted-names-council/naming-guidelines/naming-biologics/monoclonal-antibodies.page?.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 World Health Organization (2017-05-26), Revised monoclonal antibody (mAb) nomenclature scheme: Geneva, 26 May 2017, https://www.who.int/medicines/services/inn/Revised_mAb_nomenclature_scheme.pdf, retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "International Nonproprietary Names". WHO Drug Information (World Health Organization) 23 (3): 195–199. 2009. https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/druginformation/issues/DrugInfo09_Vol23-3.pdf. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ↑ "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN)". WHO Drug Information (World Health Organization) 18 (1): 61. 2004. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/druginfo/18_1_2004_INN90.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ↑ "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN)". WHO Drug Information (World Health Organization) 15 (2): 121. 2001. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/druginfo/DRUG_INFO_15_2_2001_INN-85.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ↑ Stern, M.; Herrmann, R. (2005). "Overview of monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy: present and promise". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 54 (1): 11–29. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.10.011. PMID 15780905.

- ↑ Tabrizi, M.; Tseng, C.; Roskos, L. (2006). "Elimination mechanisms of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies". Drug Discovery Today 11 (1–2): 81–88. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03638-X. PMID 16478695.

- ↑ Lordick, F.; Ott, K.; Weitz, J.; Jäger, D. (2008). "The evolving role of catumaxomab in gastric cancer". Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy 8 (9): 1407–15. doi:10.1517/14712598.8.9.1407. PMID 18694358.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Miyasaka, N. (2009). "Adalimumab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis". Expert Review of Clinical Immunology 5 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1586/1744666X.5.1.19. PMID 20476896.

- ↑ "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN)". WHO Drug Information (World Health Organization) 18 (2): 167. 2004. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/druginfo/18_2_2004_INN91.pdf. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- ↑ Veronese, F.; Pasut, G. (2005). "PEGylation, successful approach to drug delivery". Drug Discovery Today 10 (21): 1451–1458. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03575-0. PMID 16243265.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN)". WHO Drug Information (World Health Organization) 22 (3): 221. 2008. https://www.who.int/medicines/services/inn/INN_2008_list60.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ↑ "Drug Dictionary: Glembatumumab vedotin". National Cancer Institute. 2011-02-02. http://www.cancer.gov/drugdictionary/?CdrID=599456.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "ATC/DDD Classification (final)". WHO Drug Information (World Health Organization) 15 (2). 2001. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js2288e/7.html. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- ↑ "The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances". World Health Organization. 2009. pp. 107–109, 168–169. https://www.who.int/medicines/services/inn/StemBook2009.pdf.

- ↑ "Monoclonal Antibodies". 4 May 2016. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/united-states-adopted-names/monoclonal-antibodies.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 "Revised monoclonal antibody (mAb) nomenclature scheme". Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO). 26 May 2017. https://www.who.int/medicines/services/inn/Revised_mAb_nomenclature_scheme.pdf.

- ↑ International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for biological and biotechnological substances (a review) (Report). 2019. WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2019.1. https://www.who.int/medicines/services/inn/BioReview2019.pdf.

- ↑ "76.4.1: Besilesomab". Handbook of Therapeutic Antibodies (2nd ed.). Weinheim, Germany: John Wiley & Sons. 2014. p. 2131. ISBN 978-3-527-32937-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=svHsBQAAQBAJ&dq=Besilesomab&pg=PA2131.

- ↑ Entry on Stamulumab. at: Römpp Online. Georg Thieme Verlag, retrieved 2021-11-17.

- ↑ AGN (1931). "The Late Baron Shibasaburo Kitasato". Canadian Medical Association Journal 25 (2): 206. PMID 20318414.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1901". Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1901/index.html.

- ↑ Lindenmann, J. (1984). "Origin of the terms 'antibody' and 'antigen'". Scandinavian Journal of Immunology 19 (4): 281–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.1984.tb00931.x. PMID 6374880.

- ↑ Köhler, G.; Milstein, C. (2005). "Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. 1975". Journal of Immunology 174 (5): 2453–5. PMID 15728446.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1984". Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1984/index.html.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Mutschler, E.; Geisslinger, G.; Kroemer, H. K.; Schäfer-Korting, M. (2001) (in de). Arzneimittelwirkungen (8 ed.). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. p. 937. ISBN 978-3-8047-1763-3.

- ↑ "International Nonproprietary Names". Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/inn.html.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Statement on a Nonproprietary name adopted by the USAN Council: Olaratumab. American Medical Association. 2010-03-08. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/365/olaratumab.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ↑ "64th Consultation on International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances, Geneva, 4-7 April 2017 Executive Summary". World Health Organization. 2017-07-31. https://www.who.int/medicines/services/inn/64th_Executive_Summary.pdf.

- ↑ Parren, P.; Carter, P.J.; Pluckthun, A. (2017). "Changes to International Nonproprietary Names for antibody therapeutics 2017 and beyond: of mice, men and more". mAbs 9 (6): 898–906. doi:10.1080/19420862.2017.1341029. PMID 28621572.

- ↑ "Abciximab". Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/cdi/abciximab.html.

- ↑ "Trastuzumab". Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/cdi/trastuzumab.html.

- ↑ "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN)". WHO Drug Information (World Health Organization) 16 (3): 264. 2002. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/druginfo/INN_2002_list48.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ↑ International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for Pharmaceutical Substances: Names for radicals & groups comprehensive list. World Health Organization. 2002. p. 22. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s4894e/s4894e.pdf. Retrieved 2010-12-24.

- ↑ "Statement On A Nonproprietary Name Adopted By The Usan Council - Rozrolimupab". American Medical Association. https://searchusan.ama-assn.org/usan/documentDownload?uri=/unstructured/binary/usan/rozrolimupab.pdf.

- ↑ Statement on a Nonproprietary name adopted by the USAN Council: Benralizumab. American Medical Association. 2010-03-08. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/365/benralizumab.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ↑ "International nonproprietary names for pharmaceutical substances (INN): recommended INN: list 80". WHO Drug Information 32 (3): 431–2. 2018. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

|