Chemistry:Spermaceti

Spermaceti is a waxy substance found in the head cavities of the sperm whale (and, in smaller quantities, in the oils of other whales). Spermaceti is created in the spermaceti organ inside the whale's head. This organ may contain as much as 1,900 litres (500 US gal) of spermaceti.[1] It has been extracted by whalers since the 17th century for human use in cosmetics, textiles, and candles.

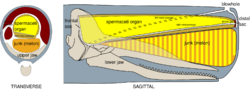

Theories for the spermaceti organ's biological function suggest that it may control buoyancy, act as a focusing apparatus for the whale's sense of echolocation, or possibly both. Concrete evidence supports both theories.[verification needed] The buoyancy theory holds that the sperm whale is capable of heating the spermaceti, lowering its density and thus allowing the whale to float; for the whale to sink again, it must take water into its blowhole, which cools the spermaceti into a denser solid. This claim has been called into question by recent research that indicates a lack of biological structures to support this heat exchange, and the fact that the change in density is too small to be meaningful until the organ grows to a huge size.[2] Measurement of the proportion of wax esters retained by a harvested sperm whale accurately described the age and future life expectancy of a given individual. The level of wax esters in the spermaceti organ increases with the age of the whale - 38–51% in calves, 58–87% in adult females, and 71–94% in adult males.[3]

Spermaceti wax is extracted from sperm oil by crystallisation at 6 °C (43 °F), when treated by pressure and a chemical solution of caustic alkali. Spermaceti forms brilliant white crystals that are hard but oily to the touch, and are devoid of taste or smell, making it very useful as an ingredient in cosmetics, leatherworking, and lubricants. The substance was also used in making candles of a standard photometric value, in the dressing of fabrics, and as a pharmaceutical excipient, especially in cerates and ointments.

The whaling industry in the 17th and 18th centuries was developed to find, harvest, and refine the contents of the head of a sperm whale. The crews seeking spermaceti routinely left on three-year tours on several oceans. Cetaceous lamp oil was a commodity that created many maritime fortunes. The light produced by a single pure spermaceti source (candle) became the standard measurement of "candlepower" for another century. Candlepower, a photometric unit defined in the United Kingdom Act of Parliament Metropolitan Gas Act 1860 and adopted at the International Electrotechnical Conference of 1883, was based on the light produced by a pure spermaceti candle.

Etymology

Spermaceti is derived from Medieval Latin sperma ceti, meaning "whale sperm" (from Latin sperma meaning "semen" or "seed", and ceti, the genitive form of "whale"). The substance was initially believed to be whale semen, due to its appearance when fresh. The substance is also the origin of the name of the sperm whale.[4][5][6]

Properties

Raw spermaceti is liquid within the head of the sperm whale, and is said to have a smell similar to raw milk.[7] It is composed mostly of wax esters (chiefly cetyl palmitate) and a smaller proportion of triglycerides.[8] Unlike other toothed whales, most of the carbon chains in the wax esters are relatively long (C

10–C

22).[3] The blubber oil of the whale is about 66% wax.[3] When it cools to 30 °C or below, the waxes begin to solidify.[9] The speed of sound in spermaceti is 2,684 m/s (at 40 kHz, 36 °C), making it nearly twice as good a conductor of sounds as the oil in a dolphin's melon.[10]

Spermaceti is insoluble in water, very slightly soluble in cold ethanol, but easily dissolved in ether, chloroform, carbon disulfide, and boiling ethanol. Spermaceti consists principally of cetyl palmitate (the ester of cetyl alcohol and palmitic acid), C

15H

31COOC

16H

33. Simple triglycerides are seen as well.

A botanical alternative to spermaceti is a derivative of jojoba oil, jojoba esters, C

19H

41COOC

20H

41, a solid wax, which is chemically and physically very similar to spermaceti and may be used in many of the same applications.

Biological function

Currently, disagreement exists on what biological purpose or purposes spermaceti serves. The proportion of wax esters retained by an average (living) whale head appears to reflect buoyancy influenced by heat. Changes in density likely enhance echolocation. It might be used as a means of adjusting the whale's buoyancy, since the density of the spermaceti changes with its phase.[11] Another hypothesis has been that it is used as a cushion to protect the sperm whale's delicate snout while diving.[12][13]

The most likely primary function of the spermaceti organ is to add internal echo or resonator clicks to the sonar echolocation clicks emitted by the respiratory organs.[14] This makes possible the whale sensing the motion of its prey and its position. The changing distance to the prey affects the time interval between the returning clicks reflected by the prey (Doppler effect). This would explain the low density and high compressibility of the spermaceti, which enhance the resonance by the contrast of the acoustic properties of the sea water and of the hard tissue surrounding the spermaceti.

Spermaceti processing

After killing a sperm whale, the whalers would pull the carcass alongside the ship, cut off the head and pull it on deck. Then, they would cut a hole in it and bail out the matter inside with a bucket. The harvested matter, raw spermaceti, was stored in casks to be processed back on land. A large whale could yield as much as 500 US gallons (1,900 l; 420 imp gal). The spermaceti was boiled and strained of impurities to prevent it from going rancid. On land, the casks were allowed to chill during the winter, causing the spermaceti to congeal into a spongy and viscous mass. The congealed matter was then loaded into wool sacks and placed in a press to squeeze out the liquid. This liquid was bottled and sold as "winter-strained sperm oil". This was the most valuable product - an oil that remained liquid in freezing winter temperatures.

Later, during the warmer seasons, the leftover solid was allowed to partially melt, and the liquid was strained off to leave a fully solid wax. This wax, brown in color, was then bleached and sold as "spermaceti wax".[15][16] Spermaceti wax is white and translucent. It melts at about 50 °C (122 °F) and congeals at 45 °C (113 °F).[17]

Gallery

-

Processing of spermaceti

-

1864 illustration captioned: "Removing the spermaceti from the head of the cachelot, or sperm whale"

-

A whaler bailing spermaceti from the severed head of a sperm whale (1874 illustration).

-

A jar of raw spermaceti

-

A sperm whale is killed, its spermaceti bailed out, and its blubber stripped and boiled in this excerpt from the 1922 movie Down to the Sea in Ships.

See also

References

- ↑ Norris, K. S.; Harvey, G. W. (January 1972). "A Theory for the Function of the Spermaceti Organ of the Sperm Whale (Physeter Catodon L.)". Nasa, Washington Animal Orientation and Navigation 262: 397. Bibcode: 1972NASSP.262..397N. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19720017437.pdf.

- ↑ Whitehead, Hal (2003-08-15). Sperm Whales: Social Evolution in the Ocean. ISBN 9780226895185. https://books.google.com/books?id=TKXdCli7nI0C&q=spermaceti+temperature&pg=PA318.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 William F. Perrin, Bernd Würsig, J. G. M. Thewissen (2002). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. p. 1164

- ↑ "Spermaceti (n.)". Spermaceti (n.). http://etymonline.com/index.php?term=spermaceti&allowed_in_frame=0.

- ↑ Wagner, Eric (December 2011). "The Sperm Whale's Deadly Call". Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-sperm-whales-deadly-call-94653/.

- ↑ Bennett, Max (29 November 2021). "Ode to the Sperm Whale". In Our Nature. https://www.inournaturemag.com/all/features/ode-to-sperm-whale-whjir3.

- ↑ William M Davis (1874). Nimrod of the Sea. Chapter 6

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://www.wdcs.org/submissions_bin/trade_report_201006.pdf.

- ↑ Malcolm R. Clarke (1978). Physical Properties of Spermaceti Oil in the Sperm Whale. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom

- ↑ Kenneth S. Norris, George W. Harvey (1972). A Theory for the Function of the Spermaceti Organ of the Sperm Whale

- ↑ Clarke, M.R. (November 1970). "Function of the Spermaceti Organ of the Sperm Whale". Nature 228 (5274): 873–874. doi:10.1038/228873a0. PMID 16058732. Bibcode: 1970Natur.228..873C.

- ↑ Christopher Grayce. Newton. Sperm whales' name, "[1]", Last accessed October 2, 2010

- ↑ Doug Lennox, Dundurn Press, 2006, Now You Know: The Book of Answers, "[2]", Last accessed October 2, 2010.

- ↑ Whitehead, Hal (2018). "Sperm Whale: Physeter macrocephalus". Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals: 919–925. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00242-9. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128043271002429. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ↑ ""Beginning with Candle Making A History of the Whaling Museum " Historic Nantucket article from the Nantucket Historical Association". Nha.org. http://www.nha.org/history/hn/HNWhalingmus.htm.

- ↑ Wilson Heflin (2004). Herman Melville's Whaling Years. pg 232

- ↑ "A practical treatise on friction, lubrication, fats and oils, including the manufacture of lubricating oils, leather oils, paint oils, solid lubricants and greases, modes of testing oils, and the application of lubricants". Philadelphia, Baird. 1916. https://archive.org/details/practicaltreatis00dietuoft.

Further reading

- Carrier, David R.; Deban, Stephen M.; Otterstrom, Jason (2002). "The face that sank the Essex: potential function of the spermaceti organ in aggression". Journal of Experimental Biology 205 (Pt 12): 1755–1763. doi:10.1242/jeb.205.12.1755. PMID 12042334. http://debanlab.org/storage/Carrieretal2002.pdf.

- Dolin, Eric Jay (2007). Leviathan, The History of Whaling in America. W.W. Norton & Co.. ISBN 978-0-393-06057-7. https://archive.org/details/leviathanhistory00doli.

|