Chord (peer-to-peer)

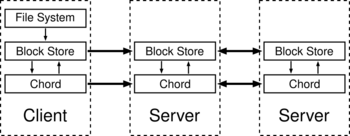

In computing, Chord is a protocol and algorithm for a peer-to-peer distributed hash table. A distributed hash table stores key-value pairs by assigning keys to different computers (known as "nodes"); a node will store the values for all the keys for which it is responsible. Chord specifies how keys are assigned to nodes, and how a node can discover the value for a given key by first locating the node responsible for that key.

Chord is one of the four original distributed hash table protocols, along with CAN, Tapestry, and Pastry. It was introduced in 2001 by Ion Stoica, Robert Morris, David Karger, Frans Kaashoek, and Hari Balakrishnan, and was developed at MIT.[1] The 2001 Chord paper[1] won an ACM SIGCOMM Test of Time award in 2011.[2]

Subsequent research by Pamela Zave has shown that the original Chord algorithm (as specified in the 2001 SIGCOMM paper,[1] the 2001 Technical report,[3] the 2002 PODC paper,[4] and the 2003 TON paper [5]) can mis-order the ring, produce several rings, and break the ring.[6]

Overview

Nodes and keys are assigned an [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math]-bit identifier using consistent hashing. The SHA-1 algorithm is the base hashing function for consistent hashing. Consistent hashing is integral to the robustness and performance of Chord because both keys and nodes (in fact, their IP addresses) are uniformly distributed in the same identifier space with a negligible possibility of collision. Thus, it also allows nodes to join and leave the network without disruption. In the protocol, the term node is used to refer to both a node itself and its identifier (ID) without ambiguity. So is the term key.

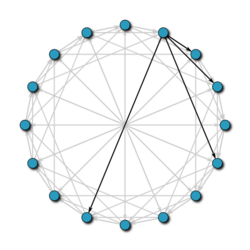

Using the Chord lookup protocol, nodes and keys are arranged in an identifier circle that has at most [math]\displaystyle{ 2^m }[/math] nodes, ranging from [math]\displaystyle{ 0 }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ 2^m - 1 }[/math]. ([math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] should be large enough to avoid collision.) Some of these nodes will map to machines or keys while others (most) will be empty.

Each node has a successor and a predecessor. The successor to a node is the next node in the identifier circle in a clockwise direction. The predecessor is counter-clockwise. If there is a node for each possible ID, the successor of node 0 is node 1, and the predecessor of node 0 is node [math]\displaystyle{ 2^m - 1 }[/math]; however, normally there are "holes" in the sequence. For example, the successor of node 153 may be node 167 (and nodes from 154 to 166 do not exist); in this case, the predecessor of node 167 will be node 153.

The concept of successor can be used for keys as well. The successor node of a key [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] is the first node whose ID equals to [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] or follows [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] in the identifier circle, denoted by [math]\displaystyle{ successor(k) }[/math]. Every key is assigned to (stored at) its successor node, so looking up a key [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] is to query [math]\displaystyle{ successor(k) }[/math].

Since the successor (or predecessor) of a node may disappear from the network (because of failure or departure), each node records an arc of [math]\displaystyle{ 2r+1 }[/math] nodes in the middle of which it stands, i.e., the list of [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] nodes preceding it and [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] nodes following it. This list results in a high probability that a node is able to correctly locate its successor or predecessor, even if the network in question suffers from a high failure rate.

Protocol details

Basic query

The core usage of the Chord protocol is to query a key from a client (generally a node as well), i.e. to find [math]\displaystyle{ successor(k) }[/math]. The basic approach is to pass the query to a node's successor, if it cannot find the key locally. This will lead to a [math]\displaystyle{ O(N) }[/math] query time where [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] is the number of machines in the ring.

Finger table

To avoid the linear search above, Chord implements a faster search method by requiring each node to keep a finger table containing up to [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] entries, recall that [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] is the number of bits in the hash key. The [math]\displaystyle{ i^{th} }[/math] entry of node [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] will contain [math]\displaystyle{ successor((n+2^{i-1})\,\bmod\,2^m) }[/math]. The first entry of finger table is actually the node's immediate successor (and therefore an extra successor field is not needed). Every time a node wants to look up a key [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math], it will pass the query to the closest successor or predecessor (depending on the finger table) of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] in its finger table (the "largest" one on the circle whose ID is smaller than [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]), until a node finds out the key is stored in its immediate successor.

With such a finger table, the number of nodes that must be contacted to find a successor in an N-node network is [math]\displaystyle{ O(\log N) }[/math]. (See proof below.)

Node join

Whenever a new node joins, three invariants should be maintained (the first two ensure correctness and the last one keeps querying fast):

- Each node's successor points to its immediate successor correctly.

- Each key is stored in [math]\displaystyle{ successor(k) }[/math].

- Each node's finger table should be correct.

To satisfy these invariants, a predecessor field is maintained for each node. As the successor is the first entry of the finger table, we do not need to maintain this field separately any more. The following tasks should be done for a newly joined node [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]:

- Initialize node [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] (the predecessor and the finger table).

- Notify other nodes to update their predecessors and finger tables.

- The new node takes over its responsible keys from its successor.

The predecessor of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] can be easily obtained from the predecessor of [math]\displaystyle{ successor(n) }[/math] (in the previous circle). As for its finger table, there are various initialization methods. The simplest one is to execute find successor queries for all [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] entries, resulting in [math]\displaystyle{ O(M\log N) }[/math] initialization time. A better method is to check whether [math]\displaystyle{ i^{th} }[/math] entry in the finger table is still correct for the [math]\displaystyle{ (i+1)^{th} }[/math] entry. This will lead to [math]\displaystyle{ O(\log^2 N) }[/math]. The best method is to initialize the finger table from its immediate neighbours and make some updates, which is [math]\displaystyle{ O(\log N) }[/math].

Stabilization

To ensure correct lookups, all successor pointers must be up to date. Therefore, a stabilization protocol is running periodically in the background which updates finger tables and successor pointers.

The stabilization protocol works as follows:

- Stabilize(): n asks its successor for its predecessor p and decides whether p should be n's successor instead (this is the case if p recently joined the system).

- Notify(): notifies n's successor of its existence, so it can change its predecessor to n

- Fix_fingers(): updates finger tables

Potential uses

- Cooperative Mirroring: A load balancing mechanism by a local network hosting information available to computers outside of the local network. This scheme could allow developers to balance the load between many computers instead of a central server to ensure availability of their product.

- Time-shared storage: In a network, once a computer joins the network its available data is distributed throughout the network for retrieval when that computer disconnects from the network. As well as other computers' data is sent to the computer in question for offline retrieval when they are no longer connected to the network. Mainly for nodes without the ability to connect full-time to the network.

- Distributed Indices: Retrieval of files over the network within a searchable database. e.g. P2P file transfer clients.

- Large scale combinatorial searches: Keys being candidate solutions to a problem and each key mapping to the node, or computer, that is responsible for evaluating them as a solution or not. e.g. Code Breaking

- Also used in wireless sensor networks for reliability[7]

Proof sketches

With high probability, Chord contacts [math]\displaystyle{ O(\log N) }[/math] nodes to find a successor in an [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math]-node network.

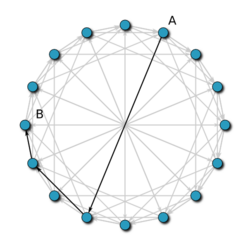

Suppose node [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] wishes to find the successor of key [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] be the predecessor of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]. We wish to find an upper bound for the number of steps it takes for a message to be routed from [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]. Node [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] will examine its finger table and route the request to the closest predecessor of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] that it has. Call this node [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math]. If [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] is the [math]\displaystyle{ i^{th} }[/math] entry in [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]'s finger table, then both [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] are at distances between [math]\displaystyle{ 2^{i-1} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ 2^{i} }[/math] from [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] along the identifier circle. Hence, the distance between [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] along this circle is at most [math]\displaystyle{ 2^{i-1} }[/math]. Thus the distance from [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] is less than the distance from [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math]: the new distance to [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] is at most half the initial distance.

This process of halving the remaining distance repeats itself, so after [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] steps, the distance remaining to [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] is at most [math]\displaystyle{ 2^m / 2^t }[/math]; in particular, after [math]\displaystyle{ \log N }[/math] steps, the remaining distance is at most [math]\displaystyle{ 2^m / N }[/math]. Because nodes are distributed uniformly at random along the identifier circle, the expected number of nodes falling within an interval of this length is 1, and with high probability, there are fewer than [math]\displaystyle{ \log N }[/math] such nodes. Because the message always advances by at least one node, it takes at most [math]\displaystyle{ \log N }[/math] steps for a message to traverse this remaining distance. The total expected routing time is thus [math]\displaystyle{ O(\log N) }[/math].

If Chord keeps track of [math]\displaystyle{ r = O(\log N) }[/math] predecessors/successors, then with high probability, if each node has probability of 1/4 of failing, find_successor (see below) and find_predecessor (see below) will return the correct nodes

Simply, the probability that all [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] nodes fail is [math]\displaystyle{ \left({{1}\over{4}}\right)^r = O\left({{1}\over{N}}\right) }[/math], which is a low probability; so with high probability at least one of them is alive and the node will have the correct pointer.

Pseudocode

- Definitions for pseudocode

-

- finger[k]

- first node that succeeds [math]\displaystyle{ (n+2^{k-1}) \mbox{ mod } 2^m, 1 \leq k \leq m }[/math]

- successor

- the next node from the node in question on the identifier ring

- predecessor

- the previous node from the node in question on the identifier ring

The pseudocode to find the successor node of an id is given below:

// ask node n to find the successor of id

n.find_successor(id)

// Yes, that should be a closing square bracket to match the opening parenthesis.

// It is a half closed interval.

if id ∈ (n, successor] then

return successor

else

// forward the query around the circle

n0 := closest_preceding_node(id)

return n0.find_successor(id)

// search the local table for the highest predecessor of id

n.closest_preceding_node(id)

for i = m downto 1 do

if (finger[i] ∈ (n, id)) then

return finger[i]

return n

The pseudocode to stabilize the chord ring/circle after node joins and departures is as follows:

// create a new Chord ring.

n.create()

predecessor := nil

successor := n

// join a Chord ring containing node n'.

n.join(n')

predecessor := nil

successor := n'.find_successor(n)

// called periodically. n asks the successor

// about its predecessor, verifies if n's immediate

// successor is consistent, and tells the successor about n

n.stabilize()

x = successor.predecessor

if x ∈ (n, successor) then

successor := x

successor.notify(n)

// n' thinks it might be our predecessor.

n.notify(n')

if predecessor is nil or n'∈(predecessor, n) then

predecessor := n'

// called periodically. refreshes finger table entries.

// next stores the index of the finger to fix

n.fix_fingers()

next := next + 1

if next > m then

next := 1

finger[next] := find_successor(n+2next-1);

// called periodically. checks whether predecessor has failed.

n.check_predecessor()

if predecessor has failed then

predecessor := nil

See also

- Kademlia

- Koorde

- OverSim – the overlay simulation framework

- SimGrid – a toolkit for the simulation of distributed applications -

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Stoica, I.; Morris, R.; Kaashoek, M. F.; Balakrishnan, H. (2001). "Chord: A scalable peer-to-peer lookup service for internet applications". ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review 31 (4): 149. doi:10.1145/964723.383071. http://pdos.csail.mit.edu/papers/chord:sigcomm01/chord_sigcomm.pdf.

- ↑ "ACM SIGCOMM Test of Time Paper Award". http://www.sigcomm.org/awards/test-of-time-paper-award.

- ↑ Template:Cite tech report

- ↑ Liben-Nowell, David; Balakrishnan, Hari; Karger, David (July 2002). "Analysis of the evolution of peer-to-peer systems". PODC '02: Proceedings of the twenty-first annual symposium on Principles of distributed computing. pp. 233–242. doi:10.1145/571825.571863. https://people.csail.mit.edu/karger/Papers/p2p-evol.pdf.

- ↑ "Chord: a scalable peer-to-peer lookup protocol for Internet applications". IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking 11 (1): 17–32. 25 February 2003. doi:10.1109/TNET.2002.808407.

- ↑ Zave, Pamela (2012). "Using lightweight modeling to understand chord". ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review 42 (2): 49–57. doi:10.1145/2185376.2185383. http://www.pamelazave.com/chord-ccr.pdf.

- ↑ Labbai, Peer Meera (Fall 2016). "T2WSN: TITIVATED TWO-TIRED CHORD OVERLAY AIDING ROBUSTNESS AND DELIVERY RATIO FOR WIRELESS SENSOR NETWORKS". Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology 91: 168–176. http://www.jatit.org/volumes/Vol91No1/18Vol91No1.pdf.

External links

- The Chord Project (redirect from: http://pdos.lcs.mit.edu/chord/)

- Open Chord – An Open Source Java Implementation

- Chordless – Another Open Source Java Implementation

- jDHTUQ- An open source java implementation. API to generalize the implementation of peer-to-peer DHT systems. Contains GUI in mode data structure

|