Source code

| Program execution |

|---|

| General concepts |

| Types of code |

| Compilation strategies |

| Notable runtimes |

|

| Notable compilers & toolchains |

|

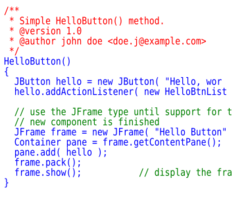

In computing, source code, or simply code, is any collection of text, with or without comments, written using a human-readable programming language, usually as plain text. The source code of a program is specially designed to facilitate the work of computer programmers, who specify the actions to be performed by a computer mostly by writing source code.

The source code is often transformed by an assembler or compiler into binary machine code that can be executed by the computer. The machine code is then available for execution at a later time.

Most application software is distributed in a form that includes only executable files. If the source code were included it would be useful to a user, programmer or a system administrator, any of whom might wish to study or modify the program.

Alternatively, depending on the technology being used, source code may be interpreted and executed directly.

Definitions

Richard Stallman's definition, formulated in his 1989 seminal license, proposed source code as whatever form in which software is modified:

The "source code" for a work means the preferred form of the work for making modifications to it.[2]

Some classical sources define source code as the text form of programming languages, for example:

Source code (also referred to as source or code) is the version of software as it is originally written (i.e., typed into a computer) by a human in plain text (i.e., human readable alphanumeric characters).[3]

This responds to the fact that, when program translation first appeared, the contemporary form of software production were textual programming languages, thus source code was text code while machine code was target code. However, as programming pipelines started to incorporate more intermediate forms, some in languages like JavaScript that could be either source or target, text code stopped being synonymous with source code.

Stallman's definition thus contemplates JavaScript and HTML's source-target ambivalence, as well as contemplating possible future forms of software production, like visual programming languages, or datasets in Machine Learning.[4][5]

Other broader interpretations, however, consider source code to include the machine code along with all the high level languages that produce it, this definition undoes the original machine/text distinction by considering each step in the program translation to be source code.

For the purpose of clarity "source code" is taken to mean any fully executable description of a software system. It is therefore so construed as to include machine code, very high level languages and executable graphical representations of systems. [6][7]

This approach allows for a much more flexible approach to system analysis, dispensing with the requirement for designer to collaborate by publishing a convenient form for understanding and modification. It can also be applied to scenarios where a designer is not needed, like DNA. However, this form of analysis does not contemplate a costlier machine-to-machine code analysis than human-to-machine code analysis.

The earliest programs for stored-program computers were entered in binary through the front panel switches of the computer. This first-generation programming language had no distinction between source code and machine code.

When IBM first offered software to work with its machine, the source code was provided at no additional charge. At that time, the cost of developing and supporting software was included in the price of the hardware. For decades, IBM distributed source code with its software product licenses, until 1983.[8]

Most early computer magazines published source code as type-in programs.

Occasionally the entire source code to a large program is published as a hardback book, such as Computers and Typesetting, vol. B: TeX, The Program by Donald Knuth, PGP Source Code and Internals by Philip Zimmermann, PC SpeedScript by Randy Thompson, and µC/OS, The Real-Time Kernel by Jean Labrosse.

Organization

The source code which constitutes a program is usually held in one or more text files stored on a computer's hard disk; usually, these files are carefully arranged into a directory tree, known as a source tree. Source code can also be stored in a database (as is common for stored procedures) or elsewhere.

The source code for a particular piece of software may be contained in a single file or many files. Though the practice is uncommon, a program's source code can be written in different programming languages.[9] For example, a program written primarily in the C programming language, might have portions written in assembly language for optimization purposes. It is also possible for some components of a piece of software to be written and compiled separately, in an arbitrary programming language, and later integrated into the software using a technique called library linking. In some languages, such as Java, this can be done at runtime (each class is compiled into a separate file that is linked by the interpreter at runtime).

Yet another method is to make the main program an interpreter for a programming language,[10] either designed specifically for the application in question or general-purpose and then write the bulk of the actual user functionality as macros or other forms of add-ins in this language, an approach taken for example by the GNU Emacs text editor.

The code base of a computer programming project is the larger collection of all the source code of all the computer programs which make up the project. It has become common practice to maintain code bases in version control systems. Moderately complex software customarily requires the compilation or assembly of several, sometimes dozens or maybe even hundreds, of different source code files. In these cases, instructions for compilations, such as a Makefile, are included with the source code. These describe the programming relationships among the source code files and contain information about how they are to be compiled.

Purposes

Source code is primarily used as input to the process that produces an executable program (i.e., it is compiled or interpreted). It is also used as a method of communicating algorithms between people (e.g., code snippets in books).[11]

Computer programmers often find it helpful to review existing source code to learn about programming techniques.[11] The sharing of source code between developers is frequently cited as a contributing factor to the maturation of their programming skills.[11] Some people consider source code an expressive artistic medium.[12]

Porting software to other computer platforms is usually prohibitively difficult without source code. Without the source code for a particular piece of software, portability is generally computationally expensive.[13] Possible porting options include binary translation and emulation of the original platform.

Decompilation of an executable program can be used to generate source code, either in assembly code or in a high-level language.

Programmers frequently adapt source code from one piece of software to use in other projects, a concept known as software reusability.

Legal aspects

The situation varies worldwide, but in the United States before 1974, software and its source code was not copyrightable and therefore always public domain software.[14]

In 1974, the US Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyrighted Works (CONTU) decided that "computer programs, to the extent that they embody an author's original creation, are proper subject matter of copyright".[15][16]

In 1983 in the United States court case Apple v. Franklin it was ruled that the same applied to object code; and that the Copyright Act gave computer programs the copyright status of literary works.

In 1999, in the United States court case Bernstein v. United States it was further ruled that source code could be considered a constitutionally protected form of free speech. Proponents of free speech argued that because source code conveys information to programmers, is written in a language, and can be used to share humor and other artistic pursuits, it is a protected form of communication.[17][18][19]

Licensing

Copyright [yyyy] [name of copyright owner]

Licensed under the Apache License, Version 2.0 (the "License"); you may not use this file except in compliance with the License. You may obtain a copy of the License at

- http://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0

Unless required by applicable law or agreed to in writing, software distributed under the License is distributed on an "AS IS" BASIS, WITHOUT WARRANTIES OR CONDITIONS OF ANY KIND, either express or implied. See the License for the specific language governing permissions and limitations under the License.

An author of a non-trivial work like software,[16] has several exclusive rights, among them the copyright for the source code and object code.[21] The author has the right and possibility to grant customers and users of his software some of his exclusive rights in form of software licensing. Software, and its accompanying source code, can be associated with several licensing paradigms; the most important distinction is free software vs proprietary software. This is done by including a copyright notice that declares licensing terms. If no notice is found, then the default of All rights reserved is implied.

Generally speaking, a software is free software if its users are free to use it for any purpose, study and change its source code, give or sell its exact copies, and give or sell its modified copies. Software is proprietary if it is distributed while the source code is kept secret, or is privately owned and restricted. One of the first software licenses to be published and to explicitly grant these freedoms was the GNU General Public License in 1989; the BSD license is another early example from 1990.

For proprietary software, the provisions of the various copyright laws, trade secrecy and patents are used to keep the source code closed. Additionally, many pieces of retail software come with an end-user license agreement (EULA) which typically prohibits decompilation, reverse engineering, analysis, modification, or circumventing of copy protection. Types of source code protection—beyond traditional compilation to object code—include code encryption, code obfuscation or code morphing.

Quality

The way a program is written can have important consequences for its maintainers. Coding conventions, which stress readability and some language-specific conventions, are aimed at the maintenance of the software source code, which involves debugging and updating. Other priorities, such as the speed of the program's execution, or the ability to compile the program for multiple architectures, often make code readability a less important consideration, since code quality generally depends on its purpose.

See also

- Bytecode

- Code as data

- Coding conventions

- Computer code

- Free software

- Legacy code

- Machine code

- Markup language

- Obfuscated code

- Object code

- Open-source software

- Package (package management system)

- Programming language

- Source code repository

- Syntax highlighting

- Visual programming language

References

- ↑ Kernighan, Brian W.. "Programming in C: A Tutorial". Bell Laboratories, Murray Hill, N. J.. http://cm.bell-labs.com/cm/cs/who/dmr/ctut.pdf.

- ↑ "The GNU General Public License v3.0". Free Software Foundation. 29 June 2007. https://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl-3.0.html.

- ↑ "Source Code Definition". February 14, 2006. http://www.linfo.org/source_code.html.

- ↑ "What is Free Software?". https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-sw.en.html.

- ↑ Stallman, Richard (2017-11-15). "The JavaScript Trap". GNU Project. https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/javascript-trap.html. Retrieved 2022-07-20.

- ↑ "Why Source Code Analysis and Manipulation Will Always Be Important" by Mark Harman, 10th IEEE International Working Conference on Source Code Analysis and Manipulation (SCAM 2010). Timișoara, Romania, 12–13 September 2010.

- ↑ "SCAM Working Conference". .

- ↑ Martin Goetz (February 8, 1988). "Object-code only: Is IBM playing fair?". Computerworld 22 (6): 59. https://books.google.com/books?id=hSBrPSYgjI4C. "It was in 1983 that IBM reversed its 20-year-old policy of distributing source code with its software product licenses.".

- ↑ "Extending and Embedding the Python Interpreter". docs.python.org. https://docs.python.org/extending/.

- ↑ "Interpreter Method - Techopedia" (in en). http://www.techopedia.com/definition/7793/interpreter.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Spinellis, D: Code Reading: The Open Source Perspective. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2003. ISBN 0-201-79940-5

- ↑ "Art and Computer Programming" ONLamp.com , (2005)

- ↑ "Software Portability - CodeProject". https://www.codeproject.com/Answers/803159/What-is-Portability.

- ↑ Liu, Joseph P.; Dogan, Stacey L. (2005). "Copyright Law and Subject Matter Specificity: The Case of Computer Software" (in en). New York University Annual Survey of American Law 61 (2). https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp/536/.

- ↑ Apple Computer, Inc. v. Franklin Computer Corporation Puts the Byte Back into Copyright Protection for Computer Programs in Golden Gate University Law Review Volume 14, Issue 2, Article 3 by Jan L. Nussbaum (January 1984)

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Lemley, Menell, Merges and Samuelson. Software and Internet Law, p. 34.

- ↑ "Info". cr.yp.to. http://cr.yp.to/export/2002/08.02-bernstein-subst.pdf.

- ↑ Bernstein v. US Department of Justice on eff.org

- ↑ EFF at 25: Remembering the Case that established Code as Speech on EFF.org by Alison Dame-Boyle (16 April 2015)

- ↑ "License". www.apache.org. https://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0.

- ↑ Hancock, Terry (2008-08-29). "What if copyright didn't apply to binary executables?". Free Software Magazine. http://www.freesoftwaremagazine.com/articles/what_if_copyright_didnt_apply_binary_executables.

Sources

- (VEW04) "Using a Decompiler for Real-World Source Recovery", M. Van Emmerik and T. Waddington, the Working Conference on Reverse Engineering, Delft, Netherlands, 9–12 November 2004. Extended version of the paper.

External links

- Source Code Definition by The Linux Information Project (LINFO)

- "Obligatory accreditation system for IT security products". MetaFilter.com. 22 September 2008. http://www.metafilter.com/75061/Obligatory-accreditation-system-for-IT-security-products. "will introduce rules requiring foreign firms to disclose secret information about digital household appliances and other products from May next year, the Yomiuri Shimbun said, citing unnamed sources. If a company refuses to disclose information, China would ban it from exporting the product to the Chinese market or producing or selling it in China, the paper said."

- Same program written in multiple languages

|