Configuration space (mathematics)

In mathematics, a configuration space is a construction closely related to state spaces or phase spaces in physics. In physics, these are used to describe the state of a whole system as a single point in a high-dimensional space. In mathematics, they are used to describe assignments of a collection of points to positions in a topological space. More specifically, configuration spaces in mathematics are particular examples of configuration spaces in physics in the particular case of several non-colliding particles.

Definition

For a topological space and a positive integer , let be the Cartesian product of copies of , equipped with the product topology. The nth (ordered) configuration space of is the set of n-tuples of pairwise distinct points in :

This space is generally endowed with the subspace topology from the inclusion of into . It is also sometimes denoted , , or .[2]

There is a natural action of the symmetric group on the points in given by

This action gives rise to the nth unordered configuration space of X,

which is the orbit space of that action. The intuition is that this action "forgets the names of the points". The unordered configuration space is sometimes denoted ,[2] , or . The collection of unordered configuration spaces over all is the Ran space, and comes with a natural topology.

Alternative formulations

For a topological space and a finite set , the configuration space of X with particles labeled by S is

For , define . Then the nth configuration space of X is , and is denoted simply .[3]

Examples

- The space of ordered configuration of two points in is homeomorphic to the product of the Euclidean 3-space with a circle, i.e. .[2]

- More generally, the configuration space of two points in is homotopy equivalent to the sphere .[4]

- The configuration space of points in is the classifying space of the th braid group (see below).

Connection to braid groups

The n-strand braid group on a connected topological space X is

the fundamental group of the nth unordered configuration space of X. The n-strand pure braid group on X is[2]

The first studied braid groups were the Artin braid groups . While the above definition is not the one that Emil Artin gave, Adolf Hurwitz implicitly defined the Artin braid groups as fundamental groups of configuration spaces of the complex plane considerably before Artin's definition (in 1891).[5]

It follows from this definition and the fact that and are Eilenberg–MacLane spaces of type , that the unordered configuration space of the plane is a classifying space for the Artin braid group, and is a classifying space for the pure Artin braid group, when both are considered as discrete groups.[6]

Configuration spaces of manifolds

If the original space is a manifold, its ordered configuration spaces are open subspaces of the powers of and are thus themselves manifolds. The configuration space of distinct unordered points is also a manifold, while the configuration space of not necessarily distinct[clarification needed] unordered points is instead an orbifold.

A configuration space is a type of classifying space or (fine) moduli space. In particular, there is a universal bundle which is a sub-bundle of the trivial bundle , and which has the property that the fiber over each point is the n element subset of classified by p.

Homotopy invariance

The homotopy type of configuration spaces is not homotopy invariant. For example, the spaces are not homotopy equivalent for any two distinct values of : is empty for , is not connected for , is an Eilenberg–MacLane space of type , and is simply connected for .

It used to be an open question whether there were examples of compact manifolds which were homotopy equivalent but had non-homotopy equivalent configuration spaces: such an example was found only in 2005 by Riccardo Longoni and Paolo Salvatore. Their example are two three-dimensional lens spaces, and the configuration spaces of at least two points in them. That these configuration spaces are not homotopy equivalent was detected by Massey products in their respective universal covers.[7] Homotopy invariance for configuration spaces of simply connected closed manifolds remains open in general, and has been proved to hold over the base field .[8][9] Real homotopy invariance of simply connected compact manifolds with simply connected boundary of dimension at least 4 was also proved.[10]

Configuration spaces of graphs

Some results are particular to configuration spaces of graphs. This problem can be related to robotics and motion planning: one can imagine placing several robots on tracks and trying to navigate them to different positions without collision. The tracks correspond to (the edges of) a graph, the robots correspond to particles, and successful navigation corresponds to a path in the configuration space of that graph.[11]

For any graph , is an Eilenberg–MacLane space of type [11] and strong deformation retracts to a CW complex of dimension , where is the number of vertices of degree at least 3.[11][12] Moreover, and deformation retract to non-positively curved cubical complexes of dimension at most .[13][14]

Configuration spaces of mechanical linkages

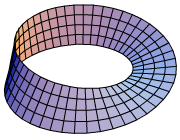

One also defines the configuration space of a mechanical linkage with the graph its underlying geometry. Such a graph is commonly assumed to be constructed as concatenation of rigid rods and hinges. The configuration space of such a linkage is defined as the totality of all its admissible positions in the Euclidean space equipped with a proper metric. The configuration space of a generic linkage is a smooth manifold, for example, for the trivial planar linkage made of rigid rods connected with revolute joints, the configuration space is the n-torus .[15][16] The simplest singularity point in such configuration spaces is a product of a cone on a homogeneous quadratic hypersurface by a Euclidean space. Such a singularity point emerges for linkages which can be divided into two sub-linkages such that their respective endpoints trace-paths intersect in a non-transverse manner, for example linkage which can be aligned (i.e. completely be folded into a line).[17]

Compactification

The configuration space of distinct points is non-compact, having ends where the points tend to approach each other (become confluent). Many geometric applications require compact spaces, so one would like to compactify , i.e., embed it as an open subset of a compact space with suitable properties. Approaches to this problem have been given by Raoul Bott and Clifford Taubes,[18] as well as William Fulton and Robert MacPherson.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ Farber, Michael; Grant, Mark (2009). "Topological complexity of configuration spaces". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 137 (5): 1841–1847. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-08-09808-0.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Ghrist, Robert (2009-12-01). "Configuration Spaces, Braids, and Robotics". in Berrick, A. Jon. Braids. Lecture Notes Series, Institute for Mathematical Sciences, National University of Singapore. 19. World Scientific. pp. 263–304. doi:10.1142/9789814291415_0004. ISBN 9789814291408.

- ↑ Chettih, Safia; Lütgehetmann, Daniel (2018). "The Homology of Configuration Spaces of Trees with Loops". Algebraic & Geometric Topology 18 (4): 2443–2469. doi:10.2140/agt.2018.18.2443.

- ↑ Sinha, Dev (2010-02-20). "The homology of the little disks operad". p. 2. arXiv:math/0610236.

- ↑ Magnus, Wilhelm (1974). "Braid groups: A survey". Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Theory of Groups. Lecture Notes in Mathematics. 372. Springer. pp. 465. doi:10.1007/BFb0065203. ISBN 978-3-540-06845-7. https://doi.org/10.1007%2FBFb0065203.

- ↑ Arnold, Vladimir (1969). "The cohomology ring of the colored braid group" (in ru). Vladimir I. Arnold — Collected Works. 5. Translated by Victor Vassiliev. pp. 227–231. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31031-7_18. ISBN 978-3-642-31030-0.

- ↑ Salvatore, Paolo; Longoni, Riccardo (2005), "Configuration spaces are not homotopy invariant", Topology 44 (2): 375–380, doi:10.1016/j.top.2004.11.002

- ↑ Campos, Ricardo; Willwacher, Thomas (2023). "A model for configuration spaces of points". Algebraic & Geometric Topology 23 (5): 2029–2106. doi:10.2140/agt.2023.23.2029.

- ↑ Idrissi, Najib (2016-08-29). "The Lambrechts–Stanley Model of Configuration Spaces". Inventiones Mathematicae 216: 1–68. doi:10.1007/s00222-018-0842-9. Bibcode: 2016arXiv160808054I. https://archive.org/details/arxiv-1608.08054.

- ↑ Campos, Ricardo; Idrissi, Najib; Lambrechts, Pascal; Willwacher, Thomas (2018-02-02). "Configuration Spaces of Manifolds with Boundary". arXiv:1802.00716 [math.AT].

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Ghrist, Robert (2001), "Configuration spaces and braid groups on graphs in robotics", Knots, braids, and mapping class groups—papers dedicated to Joan S. Birman, AMS/IP Stud. Adv. Math., 24, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, pp. 29–40

- ↑ Farley, Daniel; Sabalka, Lucas (2005). "Discrete Morse theory and graph braid groups". Algebraic & Geometric Topology 5 (3): 1075–1109. doi:10.2140/agt.2005.5.1075.

- ↑ Świątkowski, Jacek (2001). "Estimates for homological dimension of configuration spaces of graphs" (in pl). Colloquium Mathematicum 89 (1): 69–79. doi:10.4064/cm89-1-5.

- ↑ Lütgehetmann, Daniel (2014). Configuration spaces of graphs (Master’s thesis). Berlin: Free University of Berlin.

- ↑ Shvalb, Nir; Shoham, Moshe; Blanc, David (2005). "The configuration space of arachnoid mechanisms" (in en). Forum Mathematicum 17 (6): 1033–1042. doi:10.1515/form.2005.17.6.1033.

- ↑ Farber, Michael (2007). Invitation to Topological Robotics. american Mathematical Society.

- ↑ Shvalb, Nir; Blanc, David (2012). "Generic singular configurations of linkages" (in en). Topology and Its Applications 159 (3): 877–890. doi:10.1016/j.topol.2011.12.003.

- ↑ Bott, Raoul; Taubes, Clifford (1994-10-01). "On the self-linking of knots". Journal of Mathematical Physics 35 (10): 5247–5287. doi:10.1063/1.530750. ISSN 0022-2488. http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.530750.

- ↑ Fulton, William; MacPherson, Robert (January 1994). "A Compactification of Configuration Spaces". Annals of Mathematics 139 (1): 183. doi:10.2307/2946631. ISSN 0003-486X. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2946631.

|