Cubit

The cubit is an ancient unit of length based on the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger.[1] It was primarily associated with the Sumerians, Egyptians, and Israelites. The term cubit is found in the Bible regarding Noah's Ark, the Ark of the Covenant, the Tabernacle, and Solomon's Temple. The common cubit was divided into 6 palms × 4 fingers = 24 digits.[2] Royal cubits added a palm for 7 palms × 4 fingers = 28 digits.[3] These lengths typically ranged from 44.4 to 52.92 cm (1 ft 5 1⁄2 in to 1 ft 8 13⁄16 in), with an ancient Roman cubit being as long as 120 cm (3 ft 11 in).

Cubits of various lengths were employed in many parts of the world in antiquity, during the Middle Ages and as recently as early modern times. The term is still used in hedgelaying, the length of the forearm being frequently used to determine the interval between stakes placed within the hedge.[4]

Etymology

The English word "cubit" comes from the Latin noun cubitum "elbow", from the verb cubo, cubare, cubui, cubitum "to lie down",[5] from which also comes the adjective "recumbent".[6]

Ancient Egyptian royal cubit

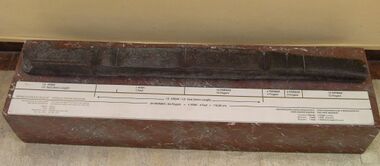

The ancient Egyptian royal cubit (meh niswt) is the earliest attested standard measure. Cubit rods were used for the measurement of length. A number of these rods have survived: two are known from the tomb of Maya, the treasurer of the 18th dynasty pharaoh Tutankhamun, in Saqqara; another was found in the tomb of Kha (TT8) in Thebes. Fourteen such rods, including one double cubit rod, were described and compared by Lepsius in 1865.[7] These cubit rods range from 523.5 to 529.2 mm (20 5⁄8 to 20 27⁄32 in) in length and are divided into seven palms; each palm is divided into four fingers, and the fingers are further subdivided.[8][7][9]

| <hiero>M23-t:n-D42</hiero>

Hieroglyph of the royal cubit, meh niswt |

Early evidence for the use of this royal cubit comes from the Early Dynastic Period: on the Palermo Stone, the flood level of the Nile river during the reign of the Pharaoh Djer is given as measuring 6 cubits and 1 palm.[8] Use of the royal cubit is also known from Old Kingdom architecture, from at least as early as the construction of the Step Pyramid of Djoser designed by Imhotep in around 2700 BC.[10]

Ancient Mesopotamian units of measurement

Ancient Mesopotamian units of measurement originated in the loosely organized city-states of Early Dynastic Sumer. Each city, kingdom and trade guild had its own standards until the formation of the Akkadian Empire when Sargon of Akkad issued a common standard. This standard was improved by Naram-Sin, but fell into disuse after the Akkadian Empire dissolved. The standard of Naram-Sin was readopted in the Ur III period by the Nanše Hymn which reduced a plethora of multiple standards to a few agreed upon common groupings. Successors to Sumerian civilization including the Babylonians, Assyrians, and Persians continued to use these groupings.

The Classical Mesopotamian system formed the basis for Elamite, Hebrew, Urartian, Hurrian, Hittite, Ugaritic, Phoenician, Babylonian, Assyrian, Persian, Arabic, and Islamic metrologies.[11] The Classical Mesopotamian System also has a proportional relationship, by virtue of standardized commerce, to Bronze Age Harappan and Egyptian metrologies.

In 1916, during the last years of the Ottoman Empire and in the middle of World War I, the German assyriologist Eckhard Unger found a copper-alloy bar while excavating at Nippur. The bar dates from c. 2650 BCE and Unger claimed it was used as a measurement standard. This irregularly formed and irregularly marked graduated rule supposedly defined the Sumerian cubit as about 518.6 mm (20 13⁄32 in).[12]

There is some evidence that cubits were used to measure angular separation. The Babylonian Astronomical Diary for 568–567 BCE refers to Jupiter being one cubit behind the elbow of Sagittarius. One cubit measures about 2 degrees.[13]

Late Assyrian cubits

Ancient Assyrian units of measure appear to exhibit significant variability. However, based on analysis of careful measurement of sculptured slabs and figures from Khorsabad, dating to the time of Sargon II, now held in Western museums, it appears that standard measures did exist.[14] This analysis, together with information from cuneiform documents from the period, confirm the existence of three Late Assyrian cubits or "kus" as the measure was called in Assyrian literature:

- The standard cubit (approximately 515 mm (20.3 in)[convert: invalid option]), used in most normal situations.

- The big cubit (566 mm (22.3 in)[convert: invalid option]) is believed to have been reserved for representations of religious and mythological beings.

- The rare cubit of the king (550 mm (22 in)[convert: invalid option]) is believed to have been used for representations of the king.

Biblical cubit

The standard of the cubit (Hebrew: אמה) in different countries and in different ages has varied. This realization led the rabbis of the 2nd century CE to clarify the length of their cubit, saying that the measure of the cubit of which they have spoken "applies to the cubit of middle-size".[15] In this case, the requirement is to make use of a standard 6 handbreadths to each cubit,[16][17] and which handbreadth was not to be confused with an outstretched palm, but rather one that was clenched and which handbreadth has the standard width of 4 fingerbreadths (each fingerbreadth being equivalent to the width of a thumb, about 2.25 cm).[18][19] This puts the handbreadth at roughly 9 cm (3 1⁄2 in), and 6 handbreadths (1 cubit) at 54 cm (21 1⁄2 in). Epiphanius of Salamis, in his treatise On Weights and Measures, describes how it was customary, in his day, to take the measurement of the biblical cubit: "The cubit is a measure, but it is taken from the measure of the forearm. For the part from the elbow to the wrist and the palm of the hand is called the cubit, the middle finger of the cubit measure being also extended at the same time and there being added below (it) the span, that is, of the hand, taken all together."[20]

Rabbi Avraham Chaim Naeh put the linear measurement of a cubit at 48 cm (19 in).[21] Avrohom Yeshaya Karelitz (the "Chazon Ish"), dissenting, put the length of a cubit at 57.6 cm (22 11⁄16 in).[22]

Rabbi and philosopher Maimonides, following the Talmud, makes a distinction between the cubit of 6 handbreadths used in ordinary measurements, and the cubit of 5 handbreadths used in measuring the Golden Altar, the base of the altar of burnt offerings, its circuit and the horns of the altar.[15]

Ancient Greece

In ancient Greek units of measurement, the standard forearm cubit (Ancient Greek: πῆχυς, romanized: pēkhys) measured approximately 460 mm (18 in). The short forearm cubit (πυγμή pygmē, lit. 'fist'), from the knuckle of the middle finger (i.e., fist clenched) to the elbow, measured approximately 340 mm (13 1⁄2 in).[23]

Ancient Rome

In ancient Rome, according to Vitruvius, a cubit was equal to 1 1⁄2 Roman feet or 6 palm widths (approximately 444 mm or 17 1⁄2 in).[24] A 120-centimetre cubit (approximately four feet long), called the Roman ulna, was common in the Roman empire, which cubit was measured from the fingers of the outstretched arm opposite the man's hip.[25]; also, [26]with[27]

Islamic world

In the Islamic world, the cubit (dhirāʿ) had a similar origin, being originally defined as the arm from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger.[28] Several different cubit lengths were current in the medieval Islamic world for the unit of length, ranging from 48.25–145.6 cm (19–57 5⁄16 in), and in turn the dhirāʿ was commonly subdivided into six handsbreadths (qabḍa), and each handsbreadth into four fingerbreadths (aṣbaʿ).[28] The most commonly used definitions were:

- the legal cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-sharʿiyya), also known as the hand cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-yad), cubit of Yusuf (al-dhirāʿ al-Yūsufiyya, named after the 8th-century qāḍī Abu Yusuf), postal cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-barīd), "freed" cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-mursala) and thread cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-ghazl). It measured 49.8 cm (19 5⁄8 in), although in the Abbasid Caliphate it measured 48.25 cm (19 in), possibly as a result of reforms of Caliph al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833).[28]

- the black cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-sawdāʾ), adopted in the Abbasid period and fixed by the measure used in the Nilometer on Rawda Island at 54.04 cm (21 1⁄4 in). It is also known as the common cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-ʿāmma), sack-cloth cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-kirbās), and was the most commonly used in the Maghreb and Islamic Spain under the name al-dhirāʿ al-Rashshāshiyya.[28]

- the king's cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-malik), inherited from the Sassanid Persians. It measured eight qabḍa for a total of 66.5 cm (26 3⁄16 in) on average. It was this measure used by Ziyad ibn Abihi for his survey of Iraq, and is hence also known as Ziyadi cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-Ziyādiyya) or survey cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-misāḥaʾ). From Caliph al-Mansur (r. 754–775) it was also known as the Hashemite cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-Hāshimiyya). Other identical measures were the work cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-ʿamal) and likely also the al-dhirāʿ al-hindāsa, which measures 65.6 cm (25 13⁄16 in).[28]

- the cloth cubit, which fluctuated widely according to region: the Egyptian cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-bazz or al-dhirāʿ al-baladiyya) measured 58.15 cm (22 29⁄32 in), that of Damascus 63 cm (25 in), that of Aleppo 67.7 cm (26 5⁄8 in), that of Baghdad 82.9 cm (32 5⁄8 in), and that of Istanbul 68.6 cm (27 in).[28]

A variety of more local or specific cubit measures were developed over time: the "small" Hashemite cubit of 60.05 cm (23 21⁄32 in), also known as the cubit of Bilal (al-dhirāʿ al-Bilāliyya, named after the 8th-century Basran qāḍī Bilal ibn Abi Burda); the Egyptian carpenter's cubit (al-dhirāʿ bi'l-najjāri) or architect's cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-miʿmāriyya) of c. 77.5 cm (30 1⁄2 in), reduced and standardized to 75 cm (29 1⁄2 in) in the 19th century; the house cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-dār) of 50.3 cm (19 13⁄16 in), introduced by the Abbasid-era qāḍī Ibn Abi Layla; the cubit of Umar (al-dhirāʿ al-ʿUmariyya) of 72.8 centimetres (28.7 in) and its double, the scale cubit (al-dhirāʿ al-mīzāniyya) established by al-Ma'mun and used mainly for measuring canals.[28]

In medieval and early modern Persia, the cubit (usually known as gaz) was either the legal cubit of 49.8 cm (19 5⁄8 in), or the Isfahan cubit of 79.8 cm (31 7⁄16 in).[28] A royal cubit (gaz-i shāhī) appeared in the 17th century with 95 cm (37 1⁄2 in), while a "shortened" cubit (gaz-i mukassar) of 6.8 cm (2 11⁄16 in) (likely derived from the widely used cloth cubit of Aleppo) was used for cloth.[28] The measure survived into the 20th century, with 1 gaz equal to 104 cm (41 in).[28] Mughal India also had its own royal cubit (dhirāʿ-i pādishāhī) of 81.3 cm (32 in).[28]

Other systems

Other measurements based on the length of the forearm include some lengths of ell, the Russian lokot (локоть), the Indian hasta, the Thai sok, the Malay hasta, the Tamil muzham, the Telugu moora (మూర), the Khmer hat, and the Tibetan khru (ཁྲུ).[29]

Cubit arm in heraldry

A cubit arm in heraldry may be dexter or sinister. It may be vested (with a sleeve) and may be shown in various positions, most commonly erect, but also fesswise (horizontal), bendwise (diagonal) and is often shown grasping objects.[30] It is most often used erect as a crest, for example by the families of Poyntz of Iron Acton, Rolle of Stevenstone and Turton.

See also

- History of measurement

- List of obsolete units of measurement

- System of measurement

- Unit of measurement

References

- ↑ "Definition of CUBIT". 2 February 2024. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cubit.

- ↑ Vitruvian Man.

- ↑ Stephen Skinner, Sacred Geometry – Deciphering The Code (Sterling, 2009) & many other sources.

- ↑ Hart, Sarah. "The Green Man". Oliver Liebscher. http://www.shropshirehedgelaying.co.uk/hedgelaying_article_3.php. "On the roadside the finish is clean and neat, a living fence of intertwined branches between stakes placed an old cubit (the length of a man's forearm or approximately 18 inches) apart."

- ↑ Cassell's Latin Dictionary

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, Second edition, 1989; online version September 2011. s.v. "cubit"

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Richard Lepsius (1865). Die altaegyptische Elle und ihre Eintheilung (in German). Berlin: Dümmler. p. 14–18.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Marshall Clagett (1999). Ancient Egyptian science, a Source Book. Volume Three: Ancient Egyptian Mathematics. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-232-0. p.

- ↑ Arnold Dieter (1991). Building in Egypt: pharaonic stone masonry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506350-9. p. 251.

- ↑ Jean Philippe Lauer (1931). "Étude sur Quelques Monuments de la IIIe Dynastie (Pyramide à Degrés de Saqqarah)". Annales du Service des Antiquités de L'Egypte IFAO 31:60 p. 59

- ↑ Conder 1908, p. 87.

- ↑ Acta praehistorica et archaeologica Volumes 7–8. Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte; Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut (Berlin, Germany); Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Berlin: Bruno Hessling Verlag, 1976. p. 49.

- ↑ Steele, John M., A Brief Introduction to Astronomy in the Middle East (SAQI, 2008), pp. 41–42. Steele does not elaborate on the relationship between the cubit as a unit of length and a unit of angular separation.

- ↑ Guralnick, Eleanor (1996). "Sargonid Sculpture and the Late Assyrian Cubit". Iraq 58: 89–103. ISSN 0021-0889.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Mishnah with Maimonides' Commentary (ed. Yosef Qafih), vol. 3, Mossad Harav Kook: Jerusalem 1967, Middot 3:1 [p. 291] (Hebrew).

- ↑ Mishnah (Kelim 17:9–10, pp. 629, note 14 – 630). In the Tosefta (Kelim Baba-Metsia 6:12–13), however, it brings down a second opinion, namely, that of Rabbi Meir, who distinguishes between a medium-sized cubit of 5 handbreadths, used principally for rabbinic measurements in measuring the bare and untilled ground near a vineyard and where there is a prohibition to grow therein seed plants under the laws of Diverse Kinds, and a larger cubit of 6 handbreadths used to measure therewith the altar. Cf. Saul Lieberman, Tosefet Rishonim (part 3), Jerusalem 1939, p. 54, s.v. איזו היא אמה בינונית, where he brings down a variant reading of the same Tosefta and where it has 6 handbreadths, instead of 5 handbreadths, for the medium size cubit.

- ↑ Cf. Warren, C. (1903) (in en). The Ancient Cubit and Our Weights and Measures. London: The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. p. 4. OCLC 752584387. https://archive.org/details/ancientcubitourw00warruoft/page/n3/mode/2up.

- ↑ Tosefta (Kelim Baba-Metsia 6:12–13)

- ↑ Mishnah with Maimonides' Commentary (ed. Yosef Qafih), vol. 1, Mossad Harav Kook: Jerusalem 1963, Kila'im 6:6 [p. 127] (Hebrew).

- ↑ Epiphanius' Treatise on Weights and Measures – the Syriac Version (ed. James Elmer Dean, The University of Chicago Press: Chicago 1935, p. 69.

- ↑ Abraham Haim Noe, Sefer Ḳuntres ha-Shiʻurim (Abridged edition from Shiʻurei Torah), Jerusalem 1943, p. 17 (section 20).

- ↑ Chazon Ish, Orach Chaim 39:14.

- ↑ Vörös, Gyozo (January–February 2015), "Anastylosis at Machaerus", Biblical Archaeology Review 41 (1): 56

- ↑ H. Arthur Klein (1974). The Science of Measurement: A Historical Survey. New York: Dover. ISBN 9780486258393. p. 68.

- ↑ Stone, Mark H. (30 January 2014). Kaushik Bose. ed. "The Cubit: A History and Measurement Commentary (Review Article)" (in en). Journal of Anthropology 2014: 489757 [4]. doi:10.1155/2014/489757.

- ↑ Grant, James (1814) (in en). Thoughts on the Origin and Descent of the Gael: With an Account of the Picts, Caledonians, and Scots; and Observations Relative to the Authenticity of the Poems of Ossian. Edinburgh: For A. Constable and Company. p. 137. https://archive.org/details/thoughtsonorigin01gran_0. Retrieved 1 January 2018. "Solinus, cap. 45, uses ulna for cubitus, where Pliny speaks of a crocodile of 22 cubits long. Solinus expresses it by so many ulnae, and Julius Pollux uses both words for the same... they call a cubitus an ulna."

- ↑ Ozdural, Alpay (1998). Necipoğlu, Gülru. ed. "Sinan's Arsin: A Survey of Ottoman Architectural Metrology" (in en). Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World (Leiden, The Netherlands) 15: 109. ISSN 0732-2992. "... Roman ulna of four feet..."ISBN 90 04 11084-4

- ↑ 28.00 28.01 28.02 28.03 28.04 28.05 28.06 28.07 28.08 28.09 28.10 Hinz (1965). "Dhirāʿ". in Lewis, B.. The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 231–232. OCLC 495469475. https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/search?s.q=Dhir%C4%81%CA%BF&s.f.s2_parent=s.f.book.encyclopaedia-of-islam-2&search-go=Search.

- ↑ Rigpa Wiki, accessed January 2022, "[1]"

- ↑ Allcock, Hubert (2003). Heraldic design : its origins, ancient forms, and modern usage, with over 500 illustrations. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. p. 24. ISBN 048642975X. https://books.google.com/books?id=TEmZhTZ3XnwC&q=cubit+arm&pg=PA24.

Bibliography

- Arnold, Dieter (2003). The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture. Taurus. ISBN 1-86064-465-1. https://archive.org/details/encyclopaediaofa00diet.

- Hirsch, Emil G. et al. (1906), "Weights and Measures", in Cyrus Adler; Gotthard Deutsch; Louis Ginzberg et al., The Jewish Encyclopedia, XII, pp. 483 ff, http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/14821-weights-and-measures.

- Petrie, Sir Flinders (1881). Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh.

- Stone, Mark H., "The Cubit: A History and Measurement Commentary", Journal of Anthropology doi:10.1155/2014/489757, 2014

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1921 Collier's Encyclopedia article Cubit. |

|