Cycloid

A cycloid is the curve traced by a point on the rim of a circular wheel as the wheel rolls along a straight line without slipping. A cycloid is a specific form of trochoid and is an example of a roulette, a curve generated by a curve rolling on another curve.

The cycloid, with the cusps pointing upward, is the curve of fastest descent under constant gravity, and is also the form of a curve for which the period of an object in descent on the curve does not depend on the object's starting position.

History

Moby Dick by Herman Melville, 1851

The cycloid has been called "The Helen of Geometers" as it caused frequent quarrels among 17th-century mathematicians.[1]

Historians of mathematics have proposed several candidates for the discoverer of the cycloid. Mathematical historian Paul Tannery cited similar work by the Syrian philosopher Iamblichus as evidence that the curve was likely known in antiquity.[2] English mathematician John Wallis writing in 1679 attributed the discovery to Nicholas of Cusa,[3] but subsequent scholarship indicates Wallis was either mistaken or the evidence used by Wallis is now lost.[4] Galileo Galilei's name was put forward at the end of the 19th century[5] and at least one author reports credit being given to Marin Mersenne.[6] Beginning with the work of Moritz Cantor[7] and Siegmund Günther,[8] scholars now assign priority to French mathematician Charles de Bovelles[9][10][11] based on his description of the cycloid in his Introductio in geometriam, published in 1503.[12] In this work, Bovelles mistakes the arch traced by a rolling wheel as part of a larger circle with a radius 120% larger than the smaller wheel.[4]

Galileo originated the term cycloid and was the first to make a serious study of the curve.[4] According to his student Evangelista Torricelli,[13] in 1599 Galileo attempted the quadrature of the cycloid (constructing a square with area equal to the area under the cycloid) with an unusually empirical approach that involved tracing both the generating circle and the resulting cycloid on sheet metal, cutting them out and weighing them. He discovered the ratio was roughly 3:1 but incorrectly concluded the ratio was an irrational fraction, which would have made quadrature impossible.[6] Around 1628, Gilles Persone de Roberval likely learned of the quadrature problem from Père Marin Mersenne and effected the quadrature in 1634 by using Cavalieri's Theorem.[4] However, this work was not published until 1693 (in his Traité des Indivisibles).[14]

Constructing the tangent of the cycloid dates to August 1638 when Mersenne received unique methods from Roberval, Pierre de Fermat and René Descartes. Mersenne passed these results along to Galileo, who gave them to his students Torricelli and Viviana, who were able to produce a quadrature. This result and others were published by Torricelli in 1644,[13] which is also the first printed work on the cycloid. This led to Roberval charging Torricelli with plagiarism, with the controversy cut short by Torricelli's early death in 1647.[14]

In 1658, Blaise Pascal had given up mathematics for theology but, while suffering from a toothache, began considering several problems concerning the cycloid. His toothache disappeared, and he took this as a heavenly sign to proceed with his research. Eight days later he had completed his essay and, to publicize the results, proposed a contest. Pascal proposed three questions relating to the center of gravity, area and volume of the cycloid, with the winner or winners to receive prizes of 20 and 40 Spanish doubloons. Pascal, Roberval and Senator Carcavy were the judges, and neither of the two submissions (by John Wallis and Antoine de Lalouvère) were judged to be adequate.[15]: 198 While the contest was ongoing, Christopher Wren sent Pascal a proposal for a proof of the rectification of the cycloid; Roberval claimed promptly that he had known of the proof for years. Wallis published Wren's proof (crediting Wren) in Wallis's Tractus Duo, giving Wren priority for the first published proof.[14]

Fifteen years later, Christiaan Huygens had deployed the cycloidal pendulum to improve chronometers and had discovered that a particle would traverse a segment of an inverted cycloidal arch in the same amount of time, regardless of its starting point. In 1686, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz used analytic geometry to describe the curve with a single equation. In 1696, Johann Bernoulli posed the brachistochrone problem, the solution of which is a cycloid.[14]

Equations

The cycloid through the origin, with a horizontal base given by the line y = 0, this line also being known as the x-axis, generated by a circle of radius r rolling over the "positive" side of the base (y ≥ 0), consists of the points (x, y), with

where t is a real parameter, corresponding to the angle through which the rolling circle has rotated. For given t, the circle's centre lies at x = rt, y = r.

Solving for t and replacing, the Cartesian equation is found to be:

An equation for the cycloid of the form y = f(x) with a closed-form expression for the right-hand side is not possible.

When y is viewed as a function of x, the cycloid is differentiable everywhere except at the cusps, where it hits the x-axis, with the derivative tending toward or as one approaches a cusp. The map from t to (x, y) is a differentiable curve or parametric curve of class C∞ and the singularity where the derivative is 0 is an ordinary cusp.

A cycloid segment from one cusp to the next is called an arch of the cycloid. The first arch of the cycloid consists of points such that

The cycloid satisfies the differential equation:

- .

Evolute

The evolute of the cycloid has the property of being exactly the same cycloid it originates from. This can otherwise be seen from the tip of a wire initially lying on a half arc of cycloid describing a cycloid arc equal to the one it was lying on once unwrapped (see also cycloidal pendulum and arc length).

Demonstration

There are several demonstrations of the assertion. The one presented here uses the physical definition of cycloid and the kinematic property that the instantaneous velocity of a point is tangent to its trajectory. Referring to the adjacent picture, and are two tangent points belonging to two rolling circles. The two circles start to roll with same speed and same direction without skidding. and start to draw two cycloid arcs as in the picture. Considering the line connecting and at an arbitrary instant (red line), it is possible to prove that the line is anytime tangent in to the lower arc and orthogonal to the tangent in of the upper arc. One sees that calling the point in common between the upper circle and the lower circle:

- are aligned because (equal rolling speed) and therefore . The point lies on the line therefore ad analogously . From the equality of and one has that also . It follows .

- If is the meeting point between the perpendicular from to the straight of and the tangent to the circle in , then the triangle is isosceles because and (easy to prove seen the construction) . For the previous noted equality between and then and is isosceles.

- Conducting from the orthogonal straight to , from the straight line tangent to the upper circle and calling the meeting point is now easy to see that is a rhombus, using the theorems concerning the angles between parallel lines

- Now consider the speed of . It can be seen as the sum of two components, the rolling speed and the drifting speed . Both speeds are equal in modulus because the circles roll without skidding. is parallel to and is tangent to the lower circle in therefore is parallel to . The rhombus constituted from the components and is therefore similar (same angles) to the rhombus because they have parallel sides. The total speed of is then parallel to because both are diagonals of two rhombuses with parallel sides and has in common with the contact point . It follows that the speed vector lies on the prolongation of . Because is tangent to the arc of cycloid in (property of velocity of a trajectory), it follows that also is coinciding with the tangent to the lower cycloid arc in .

- Analogously, it can be easily demonstrated that is orthogonal to (other diagonal of the rhombus).

- The tip of an inextensible wire initially stretched on half arc of lower cycloid and bounded to the upper circle in will then follow the point along its path without changing its length because the speed of the tip is at each moment orthogonal to the wire (no stretching or compression). The wire will be at the same time tangent in to the lower arc because the tension and the demonstrated items. If it would not be tangent then there would be a discontinuity in and consequently there would be unbalanced tension forces.

Area

One arch of a cycloid generated by a circle of radius r can be parameterized by

with

Since

the area under the arch is

This result, and some generalizations, can be obtained without calculation by Mamikon's visual calculus.

Arc length

The arc length S of one arch is given by

Another immediate way to calculate the length of the cycloid given the properties of the evolute is to notice that when a wire describing an evolute has been completely unwrapped it extends itself along two diameters, a length of 4r. Because the wire does not change length during the unwrapping it follows that the length of half an arc of cycloid is 4r and a complete arc is 8r.

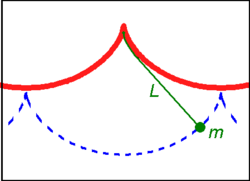

Cycloidal pendulum

If a simple pendulum is suspended from the cusp of an inverted cycloid, such that the "string" is constrained between the adjacent arcs of the cycloid, and the pendulum's length L is equal to that of half the arc length of the cycloid (i.e., twice the diameter of the generating circle, L=4r), the bob of the pendulum also traces a cycloid path. Such a cycloidal pendulum is isochronous, regardless of amplitude. Introducing a coordinate system centred in the position of the cusp, the equation of motion is given by:

where is the angle of the straight part of the string with respect to the vertical axis, and is given by

where A<1 is the "amplitude", is the radian frequency of the pendulum and g the gravitational acceleration.

The 17th-century Dutch mathematician Christiaan Huygens discovered and proved these properties of the cycloid while searching for more accurate pendulum clock designs to be used in navigation.[16]

Related curves

Several curves are related to the cycloid.

- Curtate cycloid: Here the point tracing out the curve is inside the circle, which rolls on a line.

- Prolate cycloid: Here the point tracing out the curve is outside the circle, which rolls on a line.

- Trochoid: refers to any of the cycloid, the curtate cycloid and the prolate cycloid.

- Hypocycloid: The point is on the edge of the circle, which rolls not on a line but on the inside of another circle.

- Epicycloid: The point is on the edge of the circle, which rolls not on a line but on the outside of another circle.

- Hypotrochoid: As hypocycloid but the point need not be on the edge of its circle.

- Epitrochoid: As epicycloid but the point need not be on the edge of its circle.

All these curves are roulettes with a circle rolled along a uniform curvature. The cycloid, epicycloids, and hypocycloids have the property that each is similar to its evolute. If q is the product of that curvature with the circle's radius, signed positive for epi- and negative for hypo-, then the curve:evolute similitude ratio is 1 + 2q.

The classic Spirograph toy traces out hypotrochoid and epitrochoid curves.

Use in architecture

The cycloidal arch was used by architect Louis Kahn in his design for the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. It was also used in the design of the Hopkins Center in Hanover, New Hampshire.

Use in violin plate arching

Early research indicated that some transverse arching curves of the plates of golden age violins are closely modeled by curtate cycloid curves.[17] Later work indicates that curtate cycloids do not serve as general models for these curves,[18] which vary considerably.

See also

- Roulette (curve)

- Cyclogon

- List of periodic functions

- Epicycloid

- Epitrochoid

- Hypocycloid

- Hypotrochoid

- Spirograph

- Tautochrone curve

- Brachistochrone curve

References

- ↑ Cajori, Florian (1999). A History of Mathematics. New York: Chelsea. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-8218-2102-2.

- ↑ Tannery, Paul (1883), "Pour l'histoire des lignes et surfaces courbes dans l'antiquité", Bulletin des sciences mathèmatique (Paris): 284 (cited in Whitman 1943);

- ↑ Wallis, D. (1695). "An Extract of a Letter from Dr. Wallis, of May 4. 1697, Concerning the Cycloeid Known to Cardinal Cusanus, about the Year 1450; and to Carolus Bovillus about the Year 1500". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 19 (215–235): 561. doi:10.1098/rstl.1695.0098. (Cited in Günther, p. 5)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Whitman, E. A. (May 1943), "Some historical notes on the cycloid", The American Mathematical Monthly 50 (5): 309–315, doi:10.2307/2302830

- ↑ Cajori, Florian, A History of Mathematics (5th ed.), p. 162, ISBN 0-8218-2102-4, https://books.google.com/books?id=mGJRjIC9fZgC(Note: The first (1893) edition and its reprints state that Galileo invented the cycloid. According to Phillips, this was corrected in the second (1919) edition and has remained through the most recent (fifth) edition.)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Roidt, Tom (2011). Cycloids and Paths (PDF) (MS). Portland State University. p. 4.

- ↑ Cantor, Moritz (1892), Vorlesungen über Geschichte der Mathematik, Bd. 2, Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, OCLC 25376971, https://archive.org/details/vorlesungenuberg00cant

- ↑ Günther, Siegmund (1876), Vermischte untersuchungen zur geschichte der mathematischen wissenschaften, Leipzig: Druck und Verlag Von B. G. Teubner, pp. 352, OCLC 2060559

- ↑ {{citation | title=Brachistochrone, Tautochrone, Cycloid—Apple of Discord | last=Phillips | first=J. P. | journal=The Mathematics Teacher | volume=60 | number=5 |date=May 1967 | pages=506–508 | jstor=27957609

- ↑ Victor, Joseph M. (1978), Charles de Bovelles, 1479-1553: An Intellectual Biography, p. 42, ISBN 978-2-600-03073-1, https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=bw4lM9wF1lgC

- ↑ Martin, J. (2010). "The Helen of Geometry". The College Mathematics Journal 41: 17–28. doi:10.4169/074683410X475083.

- ↑ de Bouelles, Charles (1503), Introductio in geometriam ... Liber de quadratura circuli. Liber de cubicatione sphere. Perspectiva introductio., OCLC 660960655

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Torricelli, Evangelista (1644), Opera geometrica, OCLC 55541940

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Walker, Evelyn (1932), A Study of Roberval's Traité des Indivisibles, Columbia University (cited in Whitman 1943);

- ↑ Conner, James A. (2006), Pascal's Wager: The Man Who Played Dice with God (1st ed.), HarperCollins, pp. 224, ISBN 9780060766917

- ↑ C. Huygens, "The Pendulum Clock or Geometrical Demonstrations Concerning the Motion of Pendula (sic) as Applied to Clocks," Translated by R. J. Blackwell, Iowa State University Press (Ames, Iowa, USA, 1986).

- ↑ Playfair, Q. "Curtate Cycloid Arching in Golden Age Cremonese Violin Family Instruments". Catgut Acoustical Society Journal. II 4 (7): 48–58.

- ↑ Mottola, RM (2011). "Comparison of Arching Profiles of Golden Age Cremonese Violins and Some Mathematically Generated Curves". Savart Journal 1 (1). http://savartjournal.org/index.php/sj/article/view/12.

Further reading

- An application from physics: Ghatak, A. & Mahadevan, L. Crack street: the cycloidal wake of a cylinder tearing through a sheet. Physical Review Letters, 91, (2003). link.aps.org

- Edward Kasner & James Newman (1940) Mathematics and the Imagination, pp 196–200, Simon & Schuster.

- Wells D (1991). The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Geometry. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 445–47. ISBN 0-14-011813-6.

External links

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Cycloid", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Curves/Cycloid.html.

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Cycloid". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Cycloid.html. Retrieved April 27, 2007.

- Cycloids at cut-the-knot

- A Treatise on The Cycloid and all forms of Cycloidal Curves, monograph by Richard A. Proctor, B.A. posted by Cornell University Library.

- Cycloid Curves by Sean Madsen with contributions by David von Seggern, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Cycloid on PlanetPTC (Mathcad)

- A VISUAL Approach to CALCULUS problems by Tom Apostol