De Bruijn's theorem

In a 1969 paper, Dutch mathematician Nicolaas Govert de Bruijn proved several results about packing congruent rectangular bricks (of any dimension) into larger rectangular boxes, in such a way that no space is left over. One of these results is now known as de Bruijn's theorem. According to this theorem, a "harmonic brick" (one in which each side length is a multiple of the next smaller side length) can only be packed into a box whose dimensions are multiples of the brick's dimensions.[1]

Example

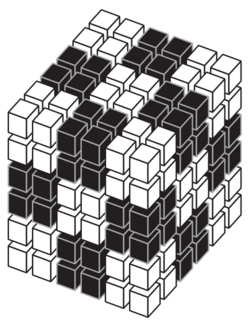

De Bruijn was led to prove this result after his then-seven-year-old son, F. W. de Bruijn, was unable to pack bricks of dimension into a cube.[2][3] The cube has a volume equal to that of bricks, but only bricks may be packed into it. One way to see this is to partition the cube into smaller cubes of size colored alternately black and white. This coloring has more unit cells of one color than of the other, but with this coloring any placement of the brick must have equal numbers of cells of each color. Therefore, any tiling by bricks would also have equal numbers of cells of each color, an impossibility.[4] De Bruijn's theorem proves that a perfect packing with these dimensions is impossible, in a more general way that applies to many other dimensions of bricks and boxes.

Boxes that are multiples of the brick

Suppose that a -dimensional rectangular box (mathematically a cuboid) has integer side lengths and a brick has lengths . If the sides of the brick can be multiplied by another set of integers so that are a permutation of , the box is called a multiple of the brick. The box can then be filled with such bricks in a trivial way with all the bricks oriented the same way.[1]

A generalization

Not every packing involves boxes that are multiples of bricks. For instance, as de Bruijn observes, a rectangular box can be filled with copies of a rectangular brick, although not with all the bricks oriented the same way. However, (de Bruijn 1969) proves that if the bricks can fill the box, then for each at least one of the is a multiple. In the above example, the side of length is a multiple of both and .[1]

Harmonic bricks

The second of de Bruijn's results, the one called de Bruijn's theorem, concerns the case where each side of the brick is an integer multiple of the next smaller side. De Bruijn calls a brick with this property harmonic. For instance, the most frequently used bricks in the USA have dimensions (in inches), which is not harmonic, but a type of brick sold as "Roman brick" has the harmonic dimensions .[5]

De Bruijn's theorem states that, if a harmonic brick is packed into a box, then the box must be a multiple of the brick. For instance, the three-dimensional harmonic brick with side lengths 1, 2, and 6 can only be packed into boxes in which one of the three sides is a multiple of six and one of the remaining two sides is even.[1][6] Packings of a harmonic brick into a box may involve copies of the brick that are rotated with respect to each other. Nevertheless, the theorem states that the only boxes that can be packed in this way are boxes that could also be packed by translates of the brick.

(Boisen 1995) provided an alternative proof of the three-dimensional case of de Bruijn's theorem, based on the algebra of polynomials.[7]

Non-harmonic bricks

The third of de Bruijn's results is that, if a brick is not harmonic, then there is a box that it can fill that is not a multiple of the brick. The packing of the brick into the box provides an example of this phenomenon.[1]

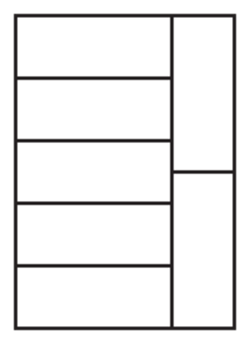

In the two-dimensional case, the third of de Bruijn's results is easy to visualize. A box with dimensions and is easy to pack with copies of a brick with dimensions , placed side by side. For the same reason, a box with dimensions and is also easy to pack with copies of the same brick. Rotating one of these two boxes so that their long sides are parallel and placing them side by side results in a packing of a larger box with and . This larger box is a multiple of the brick if and only if the brick is harmonic.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "Filling boxes with bricks", The American Mathematical Monthly 76 (1): 37–40, 1969, doi:10.2307/2316785, https://research.tue.nl/nl/publications/filling-boxes-with-bricks(e45f1645-f5f4-4f3c-8370-0a8d26d470d8).html.

- ↑ Honsberger, Ross (1976), Mathematical Gems II, Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America, p. 69, ISBN 9780883853009.

- ↑ Nienhuys, J. W. (September 11, 2011), Kloks, Ton; Hung, Ling-Ju, eds., De Bruijn's combinatorics: classroom notes, p. 156, https://books.google.com/books?id=AsXUY604pewC&pg=PA156.

- ↑ Watkins, John J. (2012), Across the Board: The Mathematics of Chessboard Problems, Princeton University Press, p. 226, ISBN 9781400840922, https://books.google.com/books?id=LtoSZmGzVs4C&pg=PA226.

- ↑ Kreh, R. T. (2003), Masonry Skills (5th ed.), Cengage Learning, p. 18, ISBN 9780766859364, https://books.google.com/books?id=e3gyN-TPRd4C&pg=PA18.

- ↑ Algebra and Tiling: Homomorphisms in the Service of Geometry, Carus Mathematical Monographs, 25, Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America, 1994, p. 52, ISBN 0-88385-028-1.

- ↑ Boisen, Paul (1995), "Polynomials and packings: a new proof of de Bruijn's theorem", Discrete Mathematics 146 (1–3): 285–287, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(94)00070-1.

External links

|