Directed percolation

This article has an unclear citation style. (September 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In statistical physics, directed percolation (DP) refers to a class of models that mimic filtering of fluids through porous materials along a given direction, due to the effect of gravity. Varying the microscopic connectivity of the pores, these models display a phase transition from a macroscopically permeable (percolating) to an impermeable (non-percolating) state. Directed percolation is also used as a simple model for epidemic spreading with a transition between survival and extinction of the disease depending on the infection rate.

More generally, the term directed percolation stands for a universality class of continuous phase transitions which are characterized by the same type of collective behavior on large scales. Directed percolation is probably the simplest universality class of transitions out of thermal equilibrium.

Lattice models

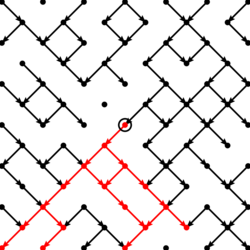

One of the simplest realizations of DP is bond directed percolation. This model is a directed variant of ordinary (isotropic) percolation and can be introduced as follows. The figure shows a tilted square lattice with bonds connecting neighboring sites. The bonds are permeable (open) with probability and impermeable (closed) otherwise. The sites and bonds may be interpreted as holes and randomly distributed channels of a porous medium.

The difference between ordinary and directed percolation is illustrated to the right. In isotropic percolation a spreading agent (e.g. water) introduced at a particular site percolates along open bonds, generating a cluster of wet sites. Contrarily, in directed percolation the spreading agent can pass open bonds only along a preferred direction in space, as indicated by the arrow. The resulting red cluster is directed in space.

As a dynamical process

Interpreting the preferred direction as a temporal degree of freedom, directed percolation can be regarded as a stochastic process that evolves in time. In a minimal, two-parameter model[1] that includes bond and site DP as special cases, a one-dimensional chain of sites evolves in discrete time , which can be viewed as a second dimension, and all sites are updated in parallel. Activating a certain site (called initial seed) at time the resulting cluster can be constructed row by row. The corresponding number of active sites varies as time evolves.

Universal scaling behavior

The DP universality class is characterized by a certain set of critical exponents. These exponents depend on the spatial dimension . Above the so-called upper critical dimension they are given by their mean-field values while in dimensions they have been estimated numerically. Current estimates are summarized in the following table:

| Exponent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Other examples

In two dimensions, the percolation of water through a thin tissue (such as toilet paper) has the same mathematical underpinnings as the flow of electricity through two-dimensional random networks of resistors. In chemistry, chromatography can be understood with similar models.

The propagation of a tear or rip in a sheet of paper, in a sheet of metal, or even the formation of a crack in ceramic bears broad mathematical resemblance to the flow of electricity through a random network of electrical fuses. Above a certain critical point, the electrical flow will cause a fuse to pop, possibly leading to a cascade of failures, resembling the propagation of a crack or tear. The study of percolation helps indicate how the flow of electricity will redistribute itself in the fuse network, thus modeling which fuses are most likely to pop next, and how fast they will pop, and what direction the crack may curve in.

Examples can be found not only in physical phenomena, but also in biology, neuroscience, ecology (e.g. evolution), and economics (e.g. diffusion of innovation).

Percolation can be considered to be a branch of the study of dynamical systems or statistical mechanics. In particular, percolation networks exhibit a phase change around a critical threshold.

Experimental realizations

In spite of vast success in the theoretical and numerical studies of DP, obtaining convincing experimental evidence has proved challenging. In 1999 an experiment on flowing sand on an inclined plane was identified as a physical realization of DP.[3] In 2007, critical behavior of DP was finally found in the electrohydrodynamic convection of liquid crystal, where a complete set of static and dynamic critical exponents and universal scaling functions of DP were measured in the transition to spatiotemporal intermittency between two turbulent states.[4][5]

See also

Sources

Literature

- Hinrichsen, Haye (2000). "Non-equilibrium critical phenomena and phase transitions into absorbing states". Advances in Physics 49 (7): 815–958. doi:10.1080/00018730050198152. ISSN 0001-8732. Bibcode: 2000AdPhy..49..815H.

- Ódor, Géza (2004-08-17). "Universality classes in nonequilibrium lattice systems". Reviews of Modern Physics 76 (3): 663–724. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.76.663. ISSN 0034-6861. Bibcode: 2004RvMP...76..663O.

- Lübeck, Sven (2004-12-30). "Universal scaling behaviour of non-equilibrium phase-transitions". International Journal of Modern Physics B (World Scientific Pub Co Pte Lt) 18 (31n32): 3977–4118. doi:10.1142/s0217979204027748. ISSN 0217-9792. Bibcode: 2004IJMPB..18.3977L.

- L. Canet: "Processus de réaction-diffusion : une approche par le groupe de renormalisation non perturbatif", Thèse. Thèse en ligne

- Muhammad Sahimi. Applications of Percolation Theory. Taylor & Francis, 1994. ISBN 0-7484-0075-3 (cloth), ISBN 0-7484-0076-1 (paper)

- Geoffrey Grimmett. Percolation (2. ed). Springer Verlag, 1999.

- Takeuchi, Kazumasa A.; Kuroda, Masafumi; Chaté, Hugues; Sano, Masaki (2007-12-05). "Directed Percolation Criticality in Turbulent Liquid Crystals". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society (APS)) 99 (23). doi:10.1103/physrevlett.99.234503. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 18233372. Bibcode: 2007PhRvL..99w4503T.

References

- ↑ Domany, Eytan; Kinzel, Wolfgang (23 July 1984). "Equivalence of Cellular Automata to Ising Models and Directed Percolation". Physical Review Letters 53 (4): 311.

- ↑ Hinrichsen, Haye (2000). "Non-equilibrium critical phenomena and phase transitions into absorbing states". Advances in Physics 49 (7): 815–958. doi:10.1080/00018730050198152. ISSN 0001-8732. Bibcode: 2000AdPhy..49..815H.

- ↑ Hinrichsen, Haye; Jimenez-Dalmaroni, Andrea; Rozov, Yadin; Domany, Eytan (13 December 1999). "Flowing Sand: A Physical Realization of Directed Percolation". Physical Review Letters 83 (24): 4999.

- ↑ Takeuchi, Kazumasa A.; Kuroda, Masafumi; Chaté, Hugues; Sano, Masaki (2007-12-05). "Directed Percolation Criticality in Turbulent Liquid Crystals". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society (APS)) 99 (23). doi:10.1103/physrevlett.99.234503. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 18233372. Bibcode: 2007PhRvL..99w4503T.

- ↑ Takeuchi, Kazumasa A.; Kuroda, Masafumi; Chaté, Hugues; Sano, Masaki (2009-11-16). "Experimental realization of directed percolation criticality in turbulent liquid crystals". Physical Review E (American Physical Society (APS)) 80 (5). doi:10.1103/physreve.80.051116. ISSN 1539-3755. PMID 20364956. Bibcode: 2009PhRvE..80e1116T.

Sources

|