Earth:Ødegården Verk

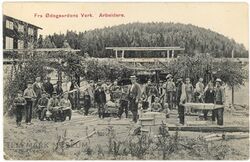

Miners at Ødegården Verk in the 1910s. Supervisor Erland Eide is in the boater hat, front center. | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 522: Unable to find the specified location map definition: "Module:Location map/data/Vestfold og Telemark" does not exist. | |

| Location | Bamble |

| County | Vestfold og Telemark |

| Country | Norway |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 58°57′39.39″N 9°33′27.86″E / 58.9609417°N 9.5577389°E |

| Production | |

| Products | Apatite, Thorite, Rutile, Titanite |

| History | |

| Opened | 1872 |

| Active | 1872–1926, 1941–1945 |

| Closed | 1945 |

| Owner | |

| Company | Compagnie Française des Mines de Bamble, Bamble Apatitt A/S |

Ødegården Verk (Ødegården Mines, French: Les Mines d'Oedegaard), alternate names Ødegården Apatittgruver and Bamble Apatittgruver, was a series of primarily apatite shaft mines and quarries located in the Bamble municipality of Norway . At its peak, Ødegården Verk was one of the largest apatite mines in the country, mining up to 10,000 metric tons of the mineral per year, and some sources estimate its peak operating workforce at over 800 men.[1][2]

The site of Ødegården Verk is about 1 km south of the E18, turning off on the road Feset between Kragerø and Brevik.[2] Apatite and other minerals were originally transported by horse and cart by local farmers from the site to one of three local ports for shipment: Åby to the east in Åbyfjorden, Brevikstranda on Brevikstrandfjorden to the southeast, or a port to the south in Isnes, just west of the modern port town Valle.[3] Later, a funicular was built between the mines and the docks at Isnes, bringing passengers as well as rocks and supplies up and down the mountain.

The dominant rock type at the deposit is a rutile-bearing scapolite-hornblende rock that was described by Norwegian geologist Waldemar Christofer Brøgger in 1934 as ødegårdite.[4] The main rock exported from Ødegårdens Verk was a special carbonate-rich hydroxylapatite (a mineral in the apatite group). Brøgger named this mineral dahllite after Tellef Dahll and his brother Johan who ran mining operations there at the time.[5]

History

In the mid-1800s, it was discovered that phosphorus, an essential nutrient that many crops lacked, could be used more effectively in fertilizer if sulfuric acid was added to phosphate rocks, creating superphosphate in the process. Almost immediately phosphate minerals such as apatite were in high demand, and it was discovered that the apatite found in Bamble was especially light in color, indicating a high concentration of phosphate. Apatite samples taken from the mines were described as course, hard lumps with a white yellowish color and an average of 85% phosphate content.[3]

The mines now known as Ødegården Verk started as two separate operations: the Østgruven and the Vestgruven, or Dahlls field, mines.[6] The Østgruven operation was started in 1872 by Compagnie Française des Mines de Bamble, a French mining company that was at the time the largest private mining enterprise in Norway. A year later, the Dalls field mines opened nearby under the ownership of Kragerø firm named Johan Dahll.

French Østgruven mines

When the Compagnie Française first started mining in 1872, the operations were supervised by director Auguste Daux, who lived in large house nearby that he named Dauxborg.[7] In 1877, Daux was succeeded by the Franco-Norwegian mining engineer Charles Antoine Delgobe, who ran the mines until 1886.[8] Unlike Daux, Delgobe made an effort to learn the Norwegian language, which made him more capable of easily communicating with the miners. Delgobe would continue living in Norway until his death in 1916, and by that time he was an influential Norwegian genealogist, civil engineer and vice consul to Belgium.[8]

Under the management of Delgobe, Østgruven was among the largest mining operations in the country: in 1880, they had 350 workers in their employ.[4] However, a few years later they fell into a decline, citing a depression in the apatite trade as the main reason. In 1885, they had a stock of nearly one million kroner's worth of goods that they judged could not be brought to market due to the sudden price drop.[9] They were forced to drastically downsize the operation to only 86 workers, leaving nearly 300 men unemployed in the process. Even on a smaller scale, the mine didn't produce enough to be profitable, and by the early 1890s they had suspended mining operations entirely. The Compagnie Française des Mines de Bamble chose to cut their losses and sold the mine to Norwegian creditors, turning their focus instead towards the Blika gold mine in Svartdal, Seljord, which they operated until the end of the century.

Dahll's Vestgruven mines

The western mines were run by Johan Dahll, a business owned by Tellef Dahll and Johan Martin Dahll that owned several mines across Telemark. The company was named after their father, Johan Georg Dahll, who was a mill- and ship-owner. The brothers were both influential geologists in their own right, but Tellef in particular was an important figure in Norway's history. Tellef Dahll was known for his work in geological surveying and standing as Stortinget member for Bratsberg (now Telemark), and he was later made a knight in both the Order of St. Olav and the Order of the Polar Star.[10]

Though the Dahll brothers' operation was smaller than the Compagnie Française's, employing only 46 men overall, it fared slightly better in the final years of the 19th century. In 1895, while the Østgruven mines were for the most part shut down, Johan Dahll exported 1,200 tonnes of apatite, earning 65 kroner per tonne for the highest-purity of these shipments.[11]

Apatite samples from the Dahll mine were among the minerals presented as part of Norway's exhibit at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.[12]

United Ødegården Verk

Ødegården Verk was combined into a single operation in 1910, when a consortium led by Håkon Mathiesen bought both mines and resumed production. In 1915, Mathiesen and the other owners formed the limited company Bamble Apatitt A/S to run the operation.[4] Erland Eide had the role of mine supervisor during this time.

The mine saw a huge upswing in demand during First World War, as millions of European farmers were drafted into the army. With fewer workers to work the fields and an skyrocketing demand for cheap food, farmers had to become more creative, using more agricultural machinery combined with synthetic fertilizers to increase the rate of production. While the Norwegian government was officially neutral during World War I, they saw the need for increasingly efficient food production, and as such they attempted to run several similar mining and prospecting operations in the district.[13]

Also in the early 1900s, the Norsk Hydro fertilizer plants were built that were a large and direct competitor to the mine. The plants were funded by French banks and used a novel technology for producing artificial fertilizer by taking nitrogen from the air. Though these plants used a lot of energy, Norway's natural capacity for hydroelectric power made them a very effective substitute for phosphate mining. During wartime, there was need for even the less efficient methods of fertilizer production, and the Great War represented one of the most productive periods in Ødegården Verk's history. However, after the end of the war, Ødegården Verk found it difficult to compete, and Bamble Apatitt A/S declared bankruptcy in 1920. Håkon Mathiesen once again took ownership of the mine and ran it himself until its closing in 1926.[6]

It wasn't until World War II that the mines were reopened. In 1941, Adam Petterson bought the mine and restored mining operations. The newly opened mine proved to be not very successful, and it was closed by the end of the war in 1945.[4]

Recent history

Between 1989 and 1992, the Norwegian Geological Survey conducted mineral exploration studies at the site of Ødegården Verk. Several economic uses of scapolite were considered, including the use of expanded scapolite as a lightweight and porous material with possible applications in construction. As the first part of the study, NGU geologist Jens Hysingjord took samples of several scapolite-bearing rocks in the Bamble area, including some at Ødegården Verk. Hysingjord noted that the rutile content of the ødegårdite rocks had economic potential, and recommended that more studies be done at the mine site.

The ødegårdite vein was discovered to be at least 1,200 m (3,900 ft) long extending north-eastwards into nearby farmland, where it has not been studied. Estimates state that the vein is composed of about 100 million metric tons of ødegårdite in total. Samples of ødegårdite taken from the mine's tailings contained 2–4% rutile content, of which 80–90% is titanium dioxide. The rutile found in ødegårdite notably contains 50–100 ppm of uranium as measured by neutron activation analysis, whereas rutile samples from eclogite contain fewer than 1 ppm of the element. The study also determined that if mining operations for rutile were to be undertaken at the site, the mine would produce REE-bearing apatite as a by-product.[4]

Little of Ødegården Verk remains today, but traces of mining activity can still be seen. Some of the tailings and quarries are still possible to find, but the mine shafts have been closed off and the entire area is overgrown by forest. Ødegården Verk's buildings, including the miners' quarters and the headframe used to bring minerals from underground, have all been demolished. The funicular is also gone: the large wooden masts were torn down, and the cables and cars sold to England. The remains of the dock at Isnes can still be seen about 300 m (980 ft) west of Valle. Some of the rocks from the old tailings were used as aggregate material for construction and road repairs in the area.[6]

Name

Ødegård, literally 'deserted farm', was a name given to many farms across Norway that became abandoned, most commonly as a result of the Black Death in the mid-1300s. As the farms became inhabited again, they sometimes kept the name, and Ødegården Verk was named after one such farm in the area. The farm Ødegård lie just northeast of the mines, on the banks of the lake that is now named Ødegårdstjenna.

The immediate area around the site of the mines is also sometimes referred to as Ødegård Verk. The local post office used the name Ødegård Verk up until it was closed in the 1990s.[14]

Gallery

Part of the Ødegården facility. Note particularly the headframe (left of center), the minecart track (lower right) and the tailings (throughout).

A portrait of Tellef Dahll: geologist, mineralogist, politician, and businessman.

References

- ↑ Raade, Gunnar. "Apatitt" (in Norwegian). Stor norske leksikon. http://snl.no/apatitt. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Axelsson, Göran (2001). "Ødegårdens verk" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090106041340/http://www.geology.neab.net/norge-2001/odegardens-verk.htm. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cohn, Wilhelm (1883). "III. Phosphorsäurehaltige Düngemittel" (in German). Die Käuflichen Düngemittel, ihre Darstellung und Verwendung. Braunschweig, Germany: Friedrich Vieweg u. Sohn. p. 20. https://books.google.com/books?id=1v5GAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA3-PA20. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Geological Survey of Norway (2010). Deposit Area: Ødegårdens Verk. http://aps.ngu.no/pls/oradb/minres_deposit_fakta.Main?p_objid=12382&p_spraak=E. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ "Dahllite". Mindat. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090309034257/http://www.mindat.org/min-4911.html. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Ødegården Apatite mines, Bamble (Bamle), Telemark, Norway". Mindat. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20121105011759/http://www.mindat.org/loc-48344.html. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ Bruland, Kristine; Kjedstadill, Knut (2005). "Immigration and industrialisation, Norway c.1840–1940". Essays on industrialisation in France, Norway and Spain. Oslo: Unipub. p. 173. ISBN 8274772059. https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/123456789/23034/86053_kjelstadli.pdf. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Delgobe" (in Danish). Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon. V: Cikorie—Demersale. Copenhagen: J. H. Schultz Forlagsboghandel. https://runeberg.org/salmonsen/2/5/1001.html. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ "Sweden and Norway". House of Commons Papers (Great Britain Foreign Office) 65: 354–355. 1895. https://books.google.com/books?id=onMTAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA354. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ Bryhni, Inge. "Tellef Dahll" (in Norwegian). Norsk biografisk leksikon. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20121021131749/http://snl.no/.nbl_biografi/Tellef_Dahll/utdypning. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ "Report on the Trade and Navigation of Norway for the Year 1895". Diplomatic and Consular Reports (Great Britain Foreign Office) 1798: 15–16. 1895. https://books.google.com/books?id=SKomAQAAIAAJ&pg=RA2-PA15. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ Kommission for Verdensutstillingen i Philadelphia (1876). "Department I. Mining and Metallurgy". Norwegian Special Catalogue for the International Exhibition at Philadelphia 1876. Christiania, Norway: B. M. Bentzen. p. 14. https://archive.org/details/norwegianspecia00goog. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ "Dybedalsgruva" (in Norwegian). Gea Norvegica Geopark. http://www.geoparken.no/Geolokaliteter/Krageroe/Dybedalsgruva. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ Flaten, Stein. "Historie" (in Norwegian). Bamble Kommune. http://www2.bamble.kommune.no/ITFBAM/add/kngwebsider.nsf/webDocuments/1E081701CA7A78DFC1256C4C00284590. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

|