Earth:Climate change and indigenous persons

Indigenous actors have a myriad experiences because of the wildly different areas they inhabit across the globe and they bring a wide variety of experiences that Western science is beginning to include in its research of climate change and its solutions.

Impact of climate change of indigenous actors

Reports show that millions of people will across the world will have to relocate due to rising seas, floods, droughts, and storms.[1] While this will affect people all over the world, the impact will disproportionately affect indigenous people in regions like the Arctic and Pacific.[1] In fact, not taking restorative action for indigenous actors could lead not only to the destruction of their lands, but could also prove genocidal for them as a whole.[1] This is because indigenous people are connected to their climate, sharing a spiritual and cultural bond with their resources, in a way that others are not. One native group in Hawaii, the Maoli, for example, believes that they are physically related to all natural things present in the island archipelago.[1] On the other hand, Westerners tend to identify not with the land they inhabit, but instead identify themselves based on their occupation.[2] Ultimately, indigenous people are the most affected by climate change and the 2009 report from the Indigenous Peoples' Global Summit on Climate Change outlines the negative effects experienced by indigenous communities in 7 regions across the globe.

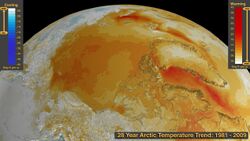

Arctic

Climate change has been the worst in the Arctic, not only with a temperature increase twice the magnitude of the increase in the rest of the world, but also with a sinking of the ice in the Arctic Sea. Satellite images of the ice show that it is currently has the smallest area in recorded history.[3] If left unchecked, climate change in the Arctic will lead to a faster rise in sea levels, more frequent and intense storms and winds, further decreases in the extent of sea ice, and increased erosion due to higher waves.[3] This climate change will also have health effects on the native Inuit people for a variety of reasons. Eroding coasts and thinning ice have changed the migration patterns of the numerous animal species upon which the Inuit rely for food.[3] Simultaneously, increased temperatures and melting permafrost will make it harder for Inuit people to freeze and store food in their traditional way. Furthermore, climate change will bring new bacteria and other micro-organisms to the region, which will bring yet unknown effects to the peoples of the region.[3]

Latin America

Extractive industries in the Amazon and the Amazonian Basin are threatening the livelihood of indigenous persons. These extractive policies were originally implemented without the consent of indigenous people are now being implemented without respect to the rights of indigenous people, specifically in the case of REDD.[3] Most indigenous groups in Latin American tropical forests still operate on a hunter-gatherer system, and have no signs of stopping while indigenous groups in the rest of the globe's tropical forests are becoming more sedentary.[4] Thus, deforestation will have a disproportionate effect on indigenous people in Latin American tropical forests. Furthermore, climate change has altered the patterns of migratory birds and changed the start and end times of wet and dry seasons, further increasing the disorientation of the daily lives of indigenous people in Latin America.[4]

Pacific

The region is characterized by low elevation and insular coastlines, making it severely susceptible to the increased sea-level and erosion effects of climate change.[3] Entire islands have sunk in the Pacific region due to climate change, dislocating and killing indigenous persons.[3] Furthermore, the region suffers from increased frequency and severity of cyclones, inundation and intensified tides, and decreased biodiversity due to the destruction of coral reefs and sea ecosystems.[3] This decrease in biodiversity is coupled with a decreased populations of the fish and other sea life the indigenous people of the region rely upon for food.[3] Indigenous people of the region are also losing many of its food sources, such as sugarcane, yams, taro, and bananas, to climate change as well as seeing a decrease in the amount of drinkable water made available from rainfall.[3]

Caribbean

The main effect of climate change in the Caribbean region is the increased occurrence of extreme weather events. There have been an influx of flash floods, tsunamis, earthquakes, extreme winds, and landslides in the region.[3] These events have led to wide-ranging infrastructural damage to both public and private property for all. For example, Hurricane Ivan inflicted damage totalling 135% of Grenada's GDP to Grenada, setting the country back an estimated ten years in development.[3] The effects of these events are most strongly felt, however, by indigenous persons, who have been forced to move to the most extreme areas of the country due to the lasting effects that colonialism had on the region.[3] In these extreme regions, extreme weather events are even more pronounced, leading to crop and livestock devastation.[3]

Asia

Indigenous people in Asia are plagued with a wide variety of problems due to climate change, including but not limited to, lengthy droughts, floods, irregular seasonal cycles, typhoons and cyclones with unprecedented strength, and highly unpredictable weather.[3] This has led to worsening food and water security, which in turn factor into an increase in water-borne diseases, heat strokes, and malnutrition.[3] Indigenous lifestyles in Asia have been completely uprooted and disrupted due to the above factors, but also due to the increased expansion of monoculture plantations, hydroelectric dams, and the extraction of uranium on their lands and territories prior to their free and informed consent.[3]

Africa

Climate change in Africa will lead to food insecurity, displacement of indigenous persons, as well as increased famine, drought, and floods.[3] In some regions of Africa, like Malawi, climate change can also lead to landslides, hailstorms, and mudslides.[5] Pressure from climate change on Africa is amplified because disaster management infrastructure is nonexistent or severely inadequate throughout the continent.[3] Furthermore, the impact of climate change in Africa falls disproportionately on indigenous people because they have limitations on their migration and mobility, are more negatively affected by decreased biodiversity, and have their agricultural land disproportionately degraded by climate change.[3] In Malawi, there has been a decrease in yield per unit hectare due to prolonged droughts and inadequate rainfall.[5]

North America

Impacts of climate change on indigenous actors in North America include temperature increases, precipitation changes, decreased glacier and snow cover, rising sea level, increased floods, droughts and extreme weather.[3] Some of the solutions proposed for combatting climate change in North America like coal pollution migitation, and GMO foods actually violate the rights of indigenous peoples and ignore what is in their best interest in favor of sustaining economic prosperity in the region.[3] Furthermore, the loss of biodiversity in the region has severely limited the ability of native people to adapt to changes in their environment.[3]

The benefits of indigenous participation in climate change research and governance

Historically, indigenous persons have not been included in conversations about climate change and frameworks for them to participate in research have not existed. For example, indigenous people in the Ecuadorian rainforest who had suffered a sharp decrease in biodiversity and an increase of greenhouse gas emissions due to the deforestation of the Amazon were not included in the 2005 Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) project.[6] This is especially difficult for indigenous people because many can perceive changes in their local climate, but struggle with giving reasons for their observed change.[5]

Critics of the program insist that their participation is necessary not only because they believe that it is necessary for social justice reasons but also because indigenous groups are better at protecting their forests than national parks.[6] This place-based knowledge rooted in local cultures, indigenous knowledge (IK), is useful in determining impacts of climate change, especially at the local level where scientific models often fail.[7] Furthermore, IK plays a crucial part in the rolling-out of new environmental programs because these programs have a higher participation rate and are more effective when indigenous actors have a say in how the programs themselves are shaped.[7] Thus, including this knowledge in climate change research would lead to further improvements in not only the REDD+ program, but also in the myriad environmental programs that have emerged and will continue to emerge throughout the new millennium.

By extension, governance, especially climate governance, would benefit from an institutional linking to IK because it would hypothetically lead to increased food security.[7] Such a linkage would also foster a shared sense of responsibility for the usage of the environment's natural resources in a way that is in line with sustainable development as a whole, but especially with the UN's Sustainable Development Goals.[7] In addition, taking governance issues to indigenous people, those who are most exposed to climate issues, would build community resilience and increase local sustainability, which would in turn lead to positive ramifications at higher levels.[7] It is theorized that harnessing the knowledge of indigenous persons on the local level is the most effective way of moving towards global sustainability.[7]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kapua'ala Sproat, D. "An Indigenous People’s Right to Environmental Self-Determination: Native Hawaiians and the Struggle Against Climate Change Devastation." Stanford Environmental Law Journal 35, no. 2.

- ↑ Gibson, Lorraine. "‘Who You Is?’ Work and Identity in Aboriginal New South Wales." In Indigenous Participation in Australian Economies: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives, 127-39. Canberra, ACT: ANU E Press, 2010.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 "Report of the Indigenous Peoples' Global Summit on Climate Change." Proceedings of Indigenous People's Global Summit on Climate Change, Alaska, Anchorage.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Macchi, Mirjam. "Indigenous and Traditional Peoples and Climate Change." IUCN, March 2008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Nkomwa, Emmanuel Charles, Miriam Kalanda Joshua, Cosmo Ngongondo, Maurice Monjerezi, and Felistus Chipungu. "Assessing Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Climate Change Adaptation Strategies in Agriculture: A Case Study of Chagaka Village, Chikhwawa, Southern Malawi." Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 67-69 (2014): 164-72. doi:10.1016/j.pce.2013.10.002.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Krause, Torsten, Wain Collen, and Kimberly A. Nicholas. "Evaluating Safeguards in a Conservation Incentive Program: Participation, Consent, and Benefit Sharing in Indigenous Communities of the Ecuadorian Amazon." Ecology and Society 18, no. 4 (2013). doi:10.5751/es-05733-180401.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Chanza, Nelson, and Anton De Wit. "Enhancing Climate Governance through Indigenous Knowledge: Case in Sustainability Science." South African Journal of Science 112, no. 3 (March/April 2016).