Earth:Doushantuo Formation

| Doushantuo Formation Stratigraphic range: Ediacaran ~635–551 Ma[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Underlies | Dengying Formation |

| Overlies | Nantuo Formation |

| Thickness | Up to 400 m; usually around 200 to 250 m |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Shale |

| Other | Mudstone, marl, carbonate or phosphate minerals |

| Location | |

| Region | South China |

| Country | China |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Doushantuo, Hubei |

| Named by | Li Siguang and Zhao Yazeng (zh) |

| Year defined | 1924[2] |

The Doushantuo Formation (formerly transcribed as Toushantuo or Toushantou,[2] from Chinese: 陡山沱; pinyin: dǒu shān tuó; literally: 'steep mountain bay') is a geological formation in western Hubei, eastern Guizhou, southern Shaanxi, central Jiangxi, and other localities in China.[3] It is known for the fossil Lagerstätten in Zigui in Hubei, Xiuning in Anhui, and Weng'an in Guizhou, as one of the oldest beds to contain minutely preserved microfossils, phosphatic fossils that are so characteristic [4] they have given their name to "Doushantuo type preservation". The formation, whose deposits date back to the Early and Middle Ediacaran,[5][1] is of particular interest because it covers the poorly understood interval of time between the end of the Cryogenian geological period and the more familiar fauna of the Late Ediacaran Avalon explosion,[6] as well as due to its microfossils' potential utility as biostratigraphical markers.[7] Taken as a whole, the Doushantuo Formation ranges from about 635 Ma (million years ago) at its base to about 551 Ma at its top, with the most fossiliferous layer predating by perhaps five Ma the earliest of the 'classical' Ediacaran faunas from Mistaken Point on the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland, and recording conditions up to a good forty to fifty million years before the Cambrian explosion at the beginning of the Phanerozoic.

Sedimentology

The whole sequence sits on an unconformity with the underlying Liantuo formation, which is free of fossils, an unconformity usually being interpreted as a period of erosion. On that unconformity lie tillites of the Nantuo formation - cemented glacial till formed of glacial deposits of cobbles and gravel laid down at the end of the Marinoan glaciation (also known as Varangian glaciation, this is the second and last of a series of very extensive glaciations during a period called the Cryogenian -- named because 'Snowball Earth' conditions at the time). This latest Cryogenian glacial level is tentatively dated ca 654 (660 ± 5) — 635 Ma (million years ago).

The Doushantuo formation itself has three layers representing aquatic sediments that formed as sea levels rose with the melting of worldwide glaciation. Biomarkers indicate highly saline conditions, such as might be found in a lagoon, low oxygen levels, and very little sediment that had been washed off land surfaces.

The richest finds (the Lagerstätte itself) lie at the bottom of the middle stratum, with a date about 570 Ma, thus from some time after the great Gaskiers glaciation of [585 ± 1 - 582.1 ± 0.4 Ma].

Fossils

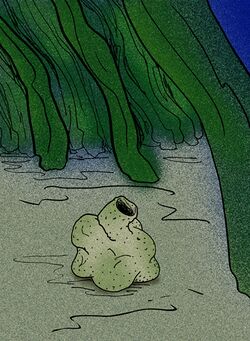

Doushantuo fossils are all aquatic, microscopic, and preserved to a great degree of detail. The latter two characteristics mean that the structure of the organisms that made them can be studied at the cellular level, and considerable insight has been gained into the embryonic and larval stages of many early creatures. One contentious claim is that many of the fossils show signs of bilateral symmetry, a common feature in many modern-day animals which is usually assumed to have evolved later, during the Cambrian Explosion. A nearly microscopic fossil animal, Vernanimalcula ("springtime micro-animal") was announced in October 2005, with the claim that it was the oldest known bilateral animal.[8] However, the absence of adult forms of almost all animal types in the Doushantuo (there are microscopic adult sponges and corals) makes these claims difficult to prove: some argue that their lack suggests these finds are not larval and embryonic forms at all; supporters contend that some unidentified process "filtered out" all but the smallest forms from fossilization. An alternative interpretation suggests that it was created by non-biological rock-forming processes.[9] The team that discovered Vernanimalcula have defended their conclusion that it was an animal, pointing out that they found ten specimens (not illustrated) of the same size and configuration, and stating that non-biological processes would be very unlikely to produce so many specimens that were so alike.[10]

The documented biota now includes phosphatized microfossils of algae, multicellular thallophytes (seaweeds), acritarchs, ciliates,[11] and cyanophytes, besides adult sponges and adult cnidarians (coelenterates; these may be early forms of tabulate corals (tetracorallians)). There also seem to be what scientists cautiously report as bilateral animal embryos, termed Parapandorina, and eggs (Megasphaera). Some of the possible animal embryos are in an early stage of cellular division (that was first interpreted as spores or algal cells), including eggs and embryos which are most probably of sponges or cnidarians, as well as adult sponges and a variety of adult cnidarians.

An alternative possibility is that the "embryos" and "eggs" are in fact fossils of giant sulfur bacteria resembling Thiomargarita, a bacterium so large that it is visible to the naked eye.[12] The interpretation would also provide a mechanism for phosphatic fossilization through microbially mediated phosphate precipitation by the bacteria, which has been observed in modern environments. If dark spots in the fossil transpire to be fossilised nuclei - an unlikely claim[13] - this would refute the Thiomargarita hypothesis. That being said, recent comparisons of the Doushantuo fossils to modern decaying Thiomargarita and expired sea urchin embryos shows little similarity between the fossils and decaying bacterial cells.[14]

Only about one-twentieth of the site's fossils have been excavated. The fossil beds are threatened by increasing intensity of phosphate mining operations in the area. A workshop led in protest by local paleontologists resulted in a temporary halt to the mining in 2017.[15]

Paleobiota

While here they are placed in the Doushantuo Formation, most of the algae are found in the Miaohe biota, which may instead belong to the lower part of the Dengying Formation.[16]

Algae

| Algae | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Higher taxon | Notes | Images | |

| Anhuiphyton | A. lineatum | Eukaryota | Essentially identical to specimens from the Lantian Formation[17] | ||

| Anomalophyton | A. zhangzhongyingi | Eukaryota | Similar to Doushantuophyton, but branches less frequently[18] | ||

| Baculiphyca | B. taeniata, B. brevistipitata | Eukaryota | Species differ in stipe length[19] | ||

| Beltanelliformis | B. brunsae | Cyanobacteria | Originally interpreted as a polypoid cnidarian[18] |  | |

| Crassitubus | C. costata | Cyanobacteria | Originally interpreted as a tubular animal,[20] before being reinterpreted as a cyanobacterium[21] | ||

| Cobios | C. rubro | Rhodophyta | Preserves evidence of multiple life stages[22] | ||

| Doushantuophyton | D. lineare, D. rigidulum, D. quyuani, D. cometa, D. laticladus | Eukaryota | Relatively small and thin[19] | ||

| Enteromorphites | E. siniansis, E. magnus | Eukaryota | One of the larger "branching algae" from Doushantuo[19] | ||

| Gemmaphyton | G. taoyingensis | Eukaryota | Bears a very long stipe and round holdfast[17] | ||

| Globusphyton | G. lineare | Eukaryota | Fairly unusual morphology suggests it likely crept along the seafloor[23] | ||

| Glomulus | G. filamentum | Cyanobacteria | Resembles modern cyanobacteria like Microcoleus[19] | ||

| Gremiphyca | G. corymbiata | Rhodophyta | Likely a stem-rhodophyte[24], resembles coralline algae[25] | ||

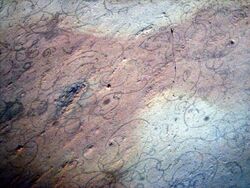

| Grypania | G. spiralis | Eukaryota? | One of the most common large Proterozoic fossils[19] |  | |

| Jiuqunaoella | J. simplicis | Eukaryota | Resembles Grypania, but differs in presence of constrictions[19] | ||

| Jixiania | J. lineata | Eukaryota? | Also known from the Mesoproterozoic, probably a filamentous alga[26] | ||

| Konglingiphyton | K. erecta, K. laterale | Rhodophyta? | Likely a rhodophyte, a formerly separate genus ("Ramalga") was actually a specimen of this genus overlaid by one of Doushantuophyton[18] | ||

| Latiortenuiphyton | L. robusta | Eukaryota | Has large vein-like structures in its thallus[17] | ||

| Liulingjitaenia | L. alloplecta | Eukaryota | Unusually consists of a set of braided filaments[19] | ||

| Longifuniculum | L. dissolutum | Eukaryota | Similar to Liulingjitaenia, but its filaments fray out at each end almost like a braided rope[19] | ||

| Maxiphyton | M. stipitatum | Eukaryota | Has an unusually thick stipe[19] | ||

| Megaspirellus | M. houi | Eukaryota | Holotype reinterpreted as a coprolite due to sediment grains[19] | ||

| Miaohephyton | M. bifurcatum | Phaeophyta? | Fossils likely represent shed fragments from larger thalli[27] | ||

| Paramecia | P. incognata | Corallinales? | Formerly interpreted as a marine lichen[25] | ||

| Paratetraphycus | P. gigantea | Bangiophyceae? | Resembles early developmental stages of the alga Porphyra[25] | ||

| Pseudodoushantuophyton | P. wenghuiensis | Eukaryota | Bears cluster-like filaments on its branches[17] | ||

| Quadratitubus | Q. orbigoniatus | Cyanobacteria | Originally interpreted as a tubular animal,[20] before being reinterpreted as a cyanobacterium[21] | ||

| Ramitubus | R. increscens, R. decrescens | Eukaryota | Originally interpreted as a tubular animal,[20] then found to be an alga similar to Epiphyton[21] | ||

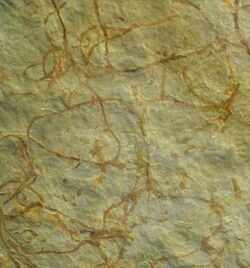

| Sinocylindra | S. linearis, S. yunnanensis | Eukaryota | Resembles the cyanobacteria Siphonophycus[19] |  | |

| Sinocyclocyclicus | S. guizhouensis | Cyanobacteria | Formerly thought to be a larval or tube-dwelling metazoan alongside other tubular microfossils[21][25] | ||

| Siphonophycus | S. solidum, S. septatum, S. kestron, S. typicum, S. robustum[26] | Cyanobacteria | Relatively common cyanobacteria[18] | ||

| Thallophyca | T. corrugata | Rhodophyta | Resembles the Solenoporaceae[25] | ||

| Thallophycoides | T. phloeatus | Eukaryota | May be a rhodophyte?[25] | ||

| Tongrenphyton | T. komma | Eukaryota | Has several filaments along its thallus, showing a clear eukaryotic affinity[17] | ||

| Vendotaenia | V. sp | Vendotaenid | Resembles specimens from the lower Cambrian[19] |  | |

| Wengania | W. globosa, W. exquisita, W. minuta[28] | Eukaryota | Resembles various algae in its parenchymatous structure, especially green algae[25] | ||

Microorganisms

| Microorganisms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Higher taxon | Notes | Images | |

| Aggregatosphaera | A. miaoheensis | Eukaryota? | Spheroidal cell clusters with similarities to algal cysts[18] | ||

| Annularidens | A. inconditus | Acritarch | Bears numerous hollow processes on its outer surface[26], giving it a gearwheel-like appearance in cross-section[29] | ||

| Apodastoides | A. basileus | Acritarch | Bears processes with plugs at their base[25] | ||

| Appendisphaera | A. anguina, A. clava, A. grandis, A. fragilis, A. longispina, A. setosa, A. tabifica, A. tenuis, A. helicaea[29], A. brevispina, A. hemisphaerica[30] | Acritarch | Bears numerous long, flexible processes[26] | ||

| Archaeophycus | A. yunnanensis | Eukaryota? | Either a cyanobacteria or the early developmental stage of an alga[26] | ||

| Asterocapsoides | A. sinicus | Acritarch | Original holotype was damaged by the surrounding rock breaking[25] | ||

| Bacatisphaera | B. baokangensis | Acritarch | Bears large pimple-like processes[31] | ||

| Baltisphaeridium | B. rigidum | Acritarch | Bears short, triangular processes[32] | ||

| Bispinosphaera[30] | B. vacua | Acritarch | Bears two separate types of process; one is conical and hollow, the other is solid and hair-like[29] | ||

| Botominella | B. lineata | Eukaryota? | Known from small trichome-like structures[26] | ||

| Castaneasphaera | C. speciosa | Acritarch | Resembles Phanerozoic "mazuelloids"[31] | ||

| Cavaspira | C. acuminata, C. basiconica | Acritarch | Bears short, conical processes[26] | ||

| Cerionopora | C. ordinata | Acritarch | May be a resting cyst of a multicellular alga[25] | ||

| Comasphaeridium | C. magnum | Acritarch | Bears long hair-like processes[32] | ||

| Crassimembrana | C. crispans, C. multitunica | Acritarch | Bears a thick vesicle wall[29] | ||

| Cyanonema | C. attenuatum | Cyanobacteria | Similar to forms from the Bitter Springs formation[30] | ||

| Cymatiosphaeroides | C. forabilatus, C. yinii[32] | Acritarch | Similar to Membranosphaera, bears cylindrical processes with pointed tips[26] | ||

| Dicrospinasphaera | D. zhangii | Acritarch | Bears thin, branching processes[32] | ||

| Distosphaera | D. jinguadunensis, D. speciosa[25] | Acritarch | Bears two layers of cylindrical processes[29] | ||

| Doushantuonema | D. peatii | Cyanobacteria | Earliest reported cyanobacteria from the formation[33] | ||

| Duospinosphaera | D. shennongjiaensis, D. biformis | Acritarch | Bears two layers of processes; an inner cylindrical one likened to hanging icicles and a larger conical one on the outer wall[26] | ||

| Echinosphaeridium | E. maximum | Acritarch | Formerly placed in Ericiasphaera due to a misinterpretation of the spines as solid[25] | ||

| Eotylotopalla | E. apophysa, E. dactylos, E. delicata[25] | Acritarch | Formerly placed within Timanisphaera[26] | ||

| Ericiasphaera | E. fibrila, E. magna, E. rigida?, E. densispina[30], E. sparsa[25] | Acritarch | Bears dense cylindrical processes[26], badly preserved acritarchs likely belonging to this genus were misinterpreted as ciliates[34] | ||

| Goniosphaeridium | G. acuminatum, G. conoideum, G. cratum | Acritarch | Similar to Baltisphaeridium[25] | ||

| Granitunica | G. mcfaddenae | Acritarch | Differs from other sphaeromorph acritarchs in its granular wall[30] | ||

| Hocosphaeridium | H. dilatatum, H. scaberfacium | Acritarch | Bears numerous hooked processes[26] | ||

| Knollisphaeridium | K. maximum, K. coniformum, K. denticulatum, K. longilatum, K. obtusum, K. parvum[30] | Acritarch | Bears conical processes with a long filament-like tip[26] | ||

| Leiosphaeridia | L. tenuissima, L. crassa, L. minutissima[26] | Acritarch | Incredibly abundant[30] | ||

| Megasphaera | M. inornata | Protista | Thought represent an animal egg, then revealed to likely be an encysting protist[35] | ||

| Meghystricosphaeridium | M. chadianensis, M?. densum, M. gracilentum, M. perfectum, M. magnificum, M. wenganensis[32] | Acritarch | Somewhat unclear which species belong to this genus[25] | ||

| Mengeosphaera | M. angusta?, M. chadianensis, M. constricta, M. gracilis, M. mamma, M. minima, M. stegosauriformis, M. bellula, M. cuspidata, M. grandispina, M. latibasis, M. spicata, M. spinula, M. triangula, M. uniformis, M. membranifera[36] | Acritarch | The species M. stegosauriformis is named after the dinosaur Stegosaurus, due to the acritarch's processes resembling the dinosaur's plates in shape[30] | ||

| Obruchevella | O. minor | Cyanobacteria | Relatively rare[26] | ||

| Oscillatoriopsis | O. amadeus, O. longa, O. obtusa, O. majuscula[26] | Cyanobacteria | Common cyanobacterial genus[30] | ||

| Osculosphaera | O. arcelliformis, O. hyalina, O. membranifera | Acritarch | Resembles arcellinids[30] | ||

| Papillomembrana | P. compta | Acritarch | Formerly placed within Dasycladales[25] | ||

| Pustulisphaera | P. membranacea | Acritarch | Bears three wall layers, with the middle one bearing pimple-like processes[25] | ||

| Salome | S. hubeiensis | Cyanobacteria | A fossil identified as a "microburrow" was placed in this genus before being reidentified as an oblique section of a tubular fossil[30] | ||

| Sarcinophycus | S. radiatus, S. papilloformis | Eukaryota? | Only known from Doushantuo, consists of bundles of sarcinoid cell packets[26] | ||

| Schizofusa | S. zangwenlongii | Acritarch | Similar to Leiosphaeridia[30] | ||

| Sinosphaera | S. asteriformis, S. rupina[25] | Acritarch | Bears small conical spines and a few larger ones[30] | ||

| Symphysosphaera | S. basimembrana | Acritarch | Similar to Eosphaera, but larger[30] | ||

| Tanarium | T. acus, T. conoideum, T. elegans, T. longitubulare, T. minimum, T. obesum, T. pilosiusculum, T. pycnacanthum, T. varium | Acritarch | Spine shapes vary from small and triangular to long and needle-like[30] | ||

| Tianzhushania | T. spinosa | Acritarch | Bears a many-layered wall with spines penetrating through it[25] | ||

| Urasphaera | U. fungiformis, U. nupta | Acritarch | Bears mushroom-shaped spines, hence the specific name fungiformis[30] | ||

| Variomargosphaeridium | V. floridum | Acritarch | Bears processes which branch at their tips[30] | ||

| Vulcanosphaera | V. phacelosa | Acritarch | Bears bundled hair-like processes[32] | ||

| Weissiella | W. grandistella | Acritarch | Doushantuo fossils resemble Russian specimens, but are smaller[30] | ||

| Xenosphaera | X. liantuoensis | Acritarch | Bears extremely thin processes, which have a tendency to not preserve[30] | ||

| Yushengia | Y. ramispina | Acritarch | Resembles Weissiella, but has longer spines[30] | ||

Miscellaneous taxa

| Miscellaneous taxa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Higher taxon | Notes | Images | |

| Cucullus | C. fraudulentus | incertae sedis | Originally interpreted as a sponge, then reinterpreted as a microbialite[37] | ||

| Paragraptobranca | P. curvus | incertae sedis | Shares features with both graptolites and macroalgae[17] | ||

| Calyptrina | C. striata | Annelida? | Almost certainly a metazoan[18] |  | |

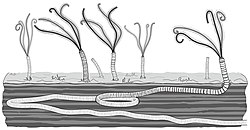

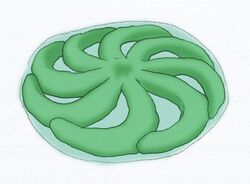

| Eoandromeda | E. octobrachiata | Ctenophora? | Originally interpreted as the adult stage of various embryos,[38] then as a pelagic discoid ctenophore,[39] then an umbrella-shaped demersal form[40] |  | |

| Eocyathispongia | E. qiania | Porifera | Earliest likely sponge fossil[41] |  | |

| Linbotulitaenia |

L. globosa |

Metazoa | Likely a trace fossil of a wriggling mucus-covered animal, possibly from Wenghuiia[17] | ||

| Protoconites | P. minor | Cnidaria? | Likely a cnidarian-grade organism[42] similar to Cambrorhytium[18] | ||

| Sinospongia | S. chenjunyuani, S. typica | Porifera? | May also be a vermiform alga like the Huainan biota[18] | ||

| Trilobozoa indet. | Unapplicable | Metazoa | Known from an undescribed triradial fossil[43] | ||

| Vernanimalcula | V. guizhouensis | Bilateria? | Originally interpreted as a bilaterian,[8] then found to be more likely an indeterminate acritarch,[9] then again found to be a likely bilaterian[44][10] | ||

| Wenghuiia | W. jiangkouensis | Annelida? | Putatively the earliest known annelid (and also the earliest known bilaterian), even though it already seems very derived[45] | ||

Palaeogeography

The formation was laid down on a carbonate shelf, whose rim enclosed a lagoon between tidal flats on the shore, and the deeper ocean. This lagoon was periodically anoxic or euxinic (containing hydrogen sulfide); variations in the chemistry in the lagoon can be detected in isotopic and elemental abundance cycles in the rock and possibly contributed to the fossil preservation.[1]

Geochemistry

The most recent Doushantuo rocks show a sharp decrease in the 13C/12C carbon isotope ratio. Since this change appears to be worldwide but its timing does not match that of any other known major event such as a mass extinction, it may represent "possible feedback relationships between evolutionary innovation and seawater chemistry" in which metazoans (multi-celled organisms) removed carbon from the water, which increased the concentration of oxygen, and the increased oxygen level made possible the evolution of new metazoans.[46]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Jiang, G.; Shi, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, S. (2011). "Stratigraphy and paleogeography of the Ediacaran Doushantuo Formation (ca. 635-551 Ma) in South China". Gondwana Research 19 (4): 831–849. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2011.01.006. Bibcode: 2011GondR..19..831J.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lee, J. S.; Chao, Y. T. (1924). "Geology of the Gorges Area of the Yangtze (from Ichang to Tzekuei) with special reference to the development of the gorges". Bulletin of the Geological Society of China 3 (3–4): 351–392. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.1924.mp33-4004.x.

- ↑ Xiao, S.; Knoll, A. H. (2000). "Phosphatized Animal Embryos from the Neoproterozoic Doushantuo Formation at Weng'an, Guizhou, South China". Journal of Paleontology 74 (5): 767–788. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2000)074<0767:PAEFTN>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Awramik, S.M.; McMenamin, D.S.; Yin, C.; Zhao, Z.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, Z. (1985). "Prokaryotic and eukaryotic microfossils from a Proterozoic/Phanerozoic transition in China". Nature 315 (6021): 655–658. doi:10.1038/315655a0. Bibcode: 1985Natur.315..655A.

- ↑ Leiming, Yin; Xunlai, Yuan (8 October 2007). "Radiation of Meso-Neoproterozoic and Early Cambrian protists inferred from the microfossil record of China". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 254 (1–2): 350–361. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.03.028. Bibcode: 2007PPP...254..350L. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031018207001903. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ↑ Chuanming, Zhou; Guwei, Xie; McFadden, Kathleen A.; Shuhai, Xiao; Xunlai, Yuan (28 November 2006). "The diversification and extinction of Doushantuo-Pertatataka acritarchs in South China: causes and biostratigraphic significance". Geological Journal 42 (3–4): 229–262. doi:10.1002/gj.1062.

- ↑ McFadden, Kathleen A.; Xiao, Shu; Chuanming, Zhou; Kowalewski, Michał (September 2009). "Quantitative evaluation of the biostratigraphic distribution of acanthomorphic acritarchs in the Ediacaran Doushantuo Formation in the Yangtze Gorges area, South China". Precambrian Research 173 (1–4): 170–190. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2009.03.009. Bibcode: 2009PreR..173..170M. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301926809000564. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Chen, Jun-Yuan; Bottjer, David J.; Oliveri, Paola; Dornbos, Stephen Q.; Gao, Feng; Ruffins, Seth; Chi, Huimei; Li, Chia-Wei et al. (9 July 2004). "Small Bilaterian Fossils from 40 to 55 Million Years Before the Cambrian" (in en). Science 305 (5681): 218–222. doi:10.1126/science.1099213. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15178752. Bibcode: 2004Sci...305..218C.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Bengtson, S.; Budd, G. (2004). "Comment on Small bilaterian fossils from 40 to 55 million years before the Cambrian". Science 306 (5700): 1291a. doi:10.1126/science.1101338. PMID 15550644.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Chen, J.Y.; Oliveri, P.; Davidson, E.; Bottjer, D.J. (2004). "Response to Comment on "Small Bilaterian Fossils from 40 to 55 Million Years Before the Cambrian"". Science 306 (5700): 1291b. doi:10.1126/science.1102328. PMID 15550644.

- ↑ {{{1}}} (2007), "{{{2}}}", in Vickers-Rich, Patricia; Komarower, Patricia, The Rise and Fall of the Ediacaran Biota, Special publications, 286, London: Geological Society, pp. {{{3}}}–{{{4}}}, doi:10.1144/SP286.{{{5}}}, ISBN 9781862392335, OCLC 156823511

- ↑ Bailey, Jake V.; Joye, SB; Kalanetra, KM; Flood, BE; Corsetti, FA (2007). "Evidence of giant sulphur bacteria in Neoproterozoic phosphorites". Nature 445 (7124): 198–201. doi:10.1038/nature05457. PMID 17183268. Bibcode: 2007Natur.445..198B.

- ↑ Schiffbauer, J. D.; Xiao, S.; Sharma, K. S.; Wang, G. (2012). "The origin of intracellular structures in Ediacaran metazoan embryos". Geology 40 (3): 223–226. doi:10.1130/G32546.1. Bibcode: 2012Geo....40..223S.

- ↑ Reardon, Sara (6 December 2011). "Dead Fossils Tell the Best Tales". ScienceNOW. http://news.sciencemag.org/sciencenow/2011/12/dead-fossils-tell-the-best-tales.html?ref=hp.

- ↑ Cyranoski, David. "Mining threatens Chinese fossil site that revealed planet's earliest animals". Nature. http://www.nature.com/news/mining-threatens-chinese-fossil-site-that-revealed-planet-s-earliest-animals-1.21869.

- ↑ Ye, Qin; An, Zhihui; Yu, Yang; Zhou, Ze; Hu, Jun; Tong, Jinnan; Xiao, Shuhai (May 2023). "Phosphatized microfossils from the Miaohe Member of South China and their implications for the terminal Ediacaran biodiversity decline". Precambrian Research 388. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2023.107001.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 Wang, Ye; Wang, Yue; Du, Wei; Wang, Xunlian (October 2016). "New Data of Macrofossils in the Ediacaran Wenghui Biota from Guizhou, South China". Acta Geologica Sinica 90 (5): 1611-1628. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Wei-Du-48/publication/310470096_New_Data_of_Macrofossils_in_the_Ediacaran_Wenghui_Biota_from_Guizhou_South_China/links/59c4b0b2aca272c71bb41abe/New-Data-of-Macrofossils-in-the-Ediacaran-Wenghui-Biota-from-Guizhou-South-China.pdf?_tp=eyJjb250ZXh0Ijp7ImZpcnN0UGFnZSI6InByb2ZpbGUiLCJwYWdlIjoicHVibGljYXRpb24iLCJwcmV2aW91c1BhZ2UiOiJwcm9maWxlIn19.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Xiao, Shuhai; Yuan, Xunlai; Steiner, Michael; Knoll, Andrew H. (2002). "Macroscopic Carbonaceous Compressions in a Terminal Proterozoic Shale: A Systematic Reassessment of the Miaohe Biota, South China". Journal of Paleontology 76 (2): 347–376. ISSN 0022-3360. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1307146.pdf.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 Ye, Qin; Tong, Jinnan; An, Zhihui; Hu, Jun; Tian, Li; Guan, Kaiping; Xiao, Shuhai (1 February 2019). "A systematic description of new macrofossil material from the upper Ediacaran Miaohe Member in South China". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 17 (3): 183–238. doi:10.1080/14772019.2017.1404499.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Liu, Pengju; Xiao, Shuhai; Yin, Chongyu; Zhou, Chuanming; Gao, Linzhi; Tang, Feng (March 2008). "SYSTEMATIC DESCRIPTION AND PHYLOGENETIC AFFINITY OF TUBULAR MICROFOSSILS FROM THE EDIACARAN DOUSHANTUO FORMATION AT WENG'AN, SOUTH CHINA". Palaeontology 51 (2): 339–366. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00762.x.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Sun, Wei-Chen; Yin, Zong-Jun; Donoghue, Philip; Liu, Peng-Ju; Shang, Xiao-Dong; Zhu, Mao-Yan (December 2019). "Tubular microfossils from the Ediacaran Weng'an Biota (Doushantuo Formation, South China) are not early animals". Palaeoworld 28 (4): 469–477. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2019.04.004.

- ↑ Du, Wei; Lian Wang, Xun; Komiya, Tsuyoshi; Zhao, Ran; Wang, Yue (2 January 2017). "Dendroid multicellular thallophytes preserved in a Neoproterozoic black phosphorite in southern China". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology 41 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/03115518.2016.1159408.

- ↑ Wang, Ye; Wang, Yue (January 2018). "Globusphyton Wang et al ., an Ediacaran Macroalga, Crept on the Seafloor in the Yangtze Block, South China". Paleontological Research 22 (1): 64–74. doi:10.2517/2017PR005.

- ↑ Xiao, Shuhai; Knoll, Andrew H.; Yuan, Xunlai; Pueschel, Curt M. (February 2004). "Phosphatized multicellular algae in the Neoproterozoic Doushantuo Formation, China, and the early evolution of florideophyte red algae". American Journal of Botany 91 (2): 214–227. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.2.214.

- ↑ 25.00 25.01 25.02 25.03 25.04 25.05 25.06 25.07 25.08 25.09 25.10 25.11 25.12 25.13 25.14 25.15 25.16 25.17 25.18 25.19 Zhang, Yun; Yin, Leiming; Xiao, Shuhai; Knoll, Andrew H. (1998). "Permineralized Fossils from the Terminal Proterozoic Doushantuo Formation, South China". Memoir (The Paleontological Society) 50: 1–52. ISSN 0078-8597. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1315592.pdf.

- ↑ 26.00 26.01 26.02 26.03 26.04 26.05 26.06 26.07 26.08 26.09 26.10 26.11 26.12 26.13 26.14 26.15 26.16 Ye, Qin; Li, Jiaqi; Tong, Jinnan; An, Zhihui; Hu, Jun; Xiao, Shuhai (August 2022). "A microfossil assemblage from the Ediacaran Doushantuo Formation in the Shennongjia area (Hubei Province, South China): Filling critical paleoenvironmental and biostratigraphic gaps". Precambrian Research 377. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2022.106691.

- ↑ Xiao, Shuhai; Knoll, Andrew H.; Yuan, Xunlai (November 1998). "Morphological reconstruction of Miaohephyton bifurcatum , a possible brown alga from the Neoproterozoic Doushantuo Formation, South China". Journal of Paleontology 72 (6): 1072–1086. doi:10.1017/S0022336000027414.

- ↑ Xiao, Shuhai (2004). "New Multicellular Algal Fossils and Acritarchs in Doushantuo Chert Nodules (Neoproterozoic; Yangtze Gorges, South China)". Journal of Paleontology 78 (2): 393–401. ISSN 0022-3360. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4094885.pdf.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 Ouyang, Qing; Zhou, Chuanming; Xiao, Shuhai; Guan, Chengguo; Chen, Zhe; Yuan, Xunlai; Sun, Yunpeng (February 2021). "Distribution of Ediacaran acanthomorphic acritarchs in the lower Doushantuo Formation of the Yangtze Gorges area, South China: Evolutionary and stratigraphic implications". Precambrian Research 353. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2020.106005.

- ↑ 30.00 30.01 30.02 30.03 30.04 30.05 30.06 30.07 30.08 30.09 30.10 30.11 30.12 30.13 30.14 30.15 30.16 30.17 30.18 30.19 Liu, Pengju; Xiao, Shuhai; Yin, Chongyu; Chen, Shouming; Zhou, Chuanming; Li, Meng (January 2014). "Ediacaran Acanthomorphic Acritarchs and Other Microfossils from Chert Nodules of the Upper Doushantuo Formation in the Yangtze Gorges Area, South China". Journal of Paleontology 88 (S72): 1–139. doi:10.1666/13-009.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Chuanming, Zhou; Brasier, M. D.; Yaosong, Xue (November 2001). "Three‐Dimensional Phosphatic Preservation Of Giant Acritarchs From The Terminal Proterozoic Doushantuo Formation In Guizhou And Hubei Provinces, South China". Palaeontology 44 (6): 1157–1178. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00219.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 Xunlai, Yuan; Hofmann, H.J. (January 1998). "New microfossils from the neoproterozoic (Sinian) Doushantuo Formation, Wengan, Guizhou Province, southwestern China". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology 22 (3): 189–222. doi:10.1080/03115519808619200.

- ↑ Zhongying, Zhang (March 1981). "A new Oscillatoriaceae-like filamentous microfossil from the Sinian (late Precambrian) of western Hubei Province, China". Geological Magazine 118 (2): 201–206. doi:10.1017/S0016756800034397.

- ↑ Dunthorn, Micah; Lipps, Jere H.; Stoeck, Thorsten (2010). "Reassessment of the Putative Ciliate Fossils Eotintinnopsis, Wujiangella, and Yonyangella from the Neoproterozoic Doushantuo Formation in China" (in en). Acta Protozoologica 49 (2): 139–144. https://ejournals.eu/en/journal/acta-protozoologica/article/reassessment-of-the-putative-ciliate-fossils-eotintinnopsis-wujiangella-and-yonyangella-from-the-neoproterozoic-doushantuo-formation-in-china.

- ↑ Zhang, Yuan; Zhang, Xingliang (June 2022). "Non-metazoan affinity of embryo-like Megasphaera fossils from the Ediacaran Zhenba microfossil assemblage". Precambrian Research 374. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2022.106645.

- ↑ Shang, Xiaodong; Liu, Pengju; Moczydłowska, Małgorzata (November 2019). "Acritarchs from the Doushantuo Formation at Liujing section in Songlin area of Guizhou Province, South China: Implications for early–middle Ediacaran biostratigraphy". Precambrian Research 334. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2019.105453.

- ↑ Antcliffe, Jonathan B.; Callow, Richard H. T.; Brasier, Martin D. (November 2014). "Giving the early fossil record of sponges a squeeze". Biological Reviews 89 (4): 972–1004. doi:10.1111/brv.12090.

- ↑ Feng, Tang; Chongyu, Yin; Bengtson, Stefan; Pengju, Liu; Ziqiang, Wang; Linzhi, Gao (February 2008). "Octoradiate Spiral Organisms in the Ediacaran of South China". Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition 82 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2008.tb00321.x.

- ↑ Tang, Feng; Bengtson, Stefan; Wang, Yue; Wang, Xun‐lian; Yin, Chong‐yu (September 2011). "Eoandromeda and the origin of Ctenophora". Evolution & Development 13 (5): 408–414. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2011.00499.x.

- ↑ Wang, Ye; Wang, Yue; Tang, Feng; Zhao, Mingsheng; Liu, Pei (1 January 2020). "Lifestyle of the Octoradiate Eoandromeda in the Ediacaran". Paleontological Research 24 (1): 1. doi:10.2517/2019PR001.

- ↑ Yin, Zongjun; Zhu, Maoyan; Davidson, Eric H.; Bottjer, David J.; Zhao, Fangchen; Tafforeau, Paul (24 March 2015). "Sponge grade body fossil with cellular resolution dating 60 Myr before the Cambrian". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (12). doi:10.1073/pnas.1414577112.

- ↑ Guo, Junfeng; Chen, Yanlong; Song, Zuchen; Zhang, Zhifei; Qiang, Yaqin; Betts, Marissa; Zheng, Yajuan; Yao, Xiaoyong (2020). "Geometric morphometric analysis of Protoconites minor from the Cambrian (Terreneuvian) Yanjiahe Formation in Three Gorges, South China". Palaeontologia Electronica. doi:10.26879/943.

- ↑ Yue, W; Xunlian, W; Yuming, H (June 2008). "Megascopic Symmetrical Metazoans from the Ediacaran Doushantuo Formation in the Northeastern Guizhou, South China". Journal of China University of Geosciences 19 (3): 200–206. doi:10.1016/S1002-0705(08)60039-4.

- ↑ Petryshyn, Victoria A.; Bottjer, David J.; Chen, Jun-Yuan; Gao, Feng (February 2013). "Petrographic analysis of new specimens of the putative microfossil Vernanimalcula guizhouena (Doushantuo Formation, South China)". Precambrian Research 225: 58–66. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2011.08.003.

- ↑ Yue, Wang; Xunlian, Wang (April 2008). "Annelid from the Neoproterozoic Doushantuo Formation in Northeastern Guizhou, China". Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition 82 (2): 257–265. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2008.tb00576.x.

- ↑ Condon, D.; Zhu, M.; Bowring, S.; Wang, W.; Yang, A.; Jin, Y. (1 April 2005). "U-Pb Ages from the Neoproterozoic Doushantuo Formation, China". Science 308 (5718): 95–98. doi:10.1126/science.1107765. PMID 15731406. Bibcode: 2005Sci...308...95C.

References

- Hagadorn, J. W.; Xiao, S; Donoghue, PC; Bengtson, S; Gostling, NJ; Pawlowska, M; Raff, EC; Raff, RA et al. (2006). "Cellular and Subcellular Structure of Neoproterozoic Animal Embryos". Science 314 (5797): 291–294. doi:10.1126/science.1133129. PMID 17038620. Bibcode: 2006Sci...314..291H.

- Knoll, A. H., 2003. Life on a Young Planet. Princeton Univ. Press.

- Xiao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Knoll, A. H. (1998). "Three-dimensional preservation of algae and animal embryos in a Neoproterozoic phosphorite". Nature 391 (6667): 553–558. doi:10.1038/35318. Bibcode: 1998Natur.391..553X.

External links

|