Earth:Eurasianism

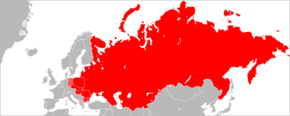

Eurasianism (Russian: евразийство, yevraziystvo) is a political movement in Russia which states that Russia does not belong in the "European" or "Asian" categories but instead to the geopolitical concept of Eurasia governed by the "Russian world" (Russian: Русский мир), forming an ostensibly standalone Russian civilization. Historically, the Russian Empire was Euro-centric and generally considered a European/Western power.

Drawing on historical, geographical, ethnographical, linguistic, musicological and religious studies, the Eurasianists suggested that the lands of the Russian Empire, and then of the Soviet Union, formed a natural unity. The first Eurasianists were mostly Émigrés, pacifists, and their vision of the future had features of romanticism and utopianism. The goal of the Eurasianists was the unification of the main Christian churches under the leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church.[1] Eurasianism was never attracted to violence and war as a way to regenerate humanity.[2] A key feature of Eurasianism is the rejection of Russian ethnic nationalism that seeks a purely Slavic state. The Eurasianists strongly opposed the territorial fragmentation of the Russian Imperial state that had followed in the wake of the revolution and civil war, and they used their geo-historical theories to insist on the necessity of the geopolitical reconstruction of the Russian state as a unified Eurasian great power.[3] Unlike many of the white Russians, the Eurasianists rejected all hope for a restoration of the monarchy.[4] Aversion to democracy is an important characteristic of Eurasianism. Eurasianists considered ideocracy a good thing, provided that the ruling ideas were the right ones.[5]

To be able to return some émigrés became supportive of the Bolshevik Revolution, but not its stated goals of building communism, seeing the Soviet Union as a steppingstone on the path to creating a new national identity that would reflect the unique character of Russia's geopolitical situation. The Eurasian movement saw a minor resurgence after the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the 20th century, and is mirrored by Turanism in Turkic and Finnic nations.

Early 20th century

Eurasianism is a political movement that has its origins in the Russian émigré community in the 1920s. The movement posited that Russian civilization does not belong in the "European" category (somewhat borrowing from Slavophile ideas of Konstantin Leontiev), and that the October Revolution of the Bolsheviks was a necessary reaction to the rapid modernization of Russian society. The Eurasianists believed that the Soviet regime was capable of evolving into a new national, non-European Orthodox Christian government in Eastern Europe and Siberia, shedding the initial mask of proletarian internationalism and militant atheism (to which the Eurasianists were strongly opposed).[citation needed]

Some of the Eurasianists criticized the anti-Bolshevik activities of organizations such as ROVS, believing that the émigré community's energies would be better focused on preparing for this hoped for process of evolution. In turn, their opponents among the emigres argued that the Eurasianists were calling for a compromise with and even support of the Soviet regime, while justifying its ruthless policies (such as the persecution of the Russian Orthodox Church and demolition of churches) as mere "transitory problems" that were inevitable results of the revolutionary process.

The key leaders of the Eurasianists were Prince Nikolai Trubetzkoy, Pyotr Savitsky, Pyotr Suvchinsky, D.S. Mirsky, Konstantin Chkheidze, Pyotr Arapov, Lev Karsavin, and Sergei Efron. Philosopher Georges Florovsky was initially a supporter, but backed out of the organization claiming it "raises the right questions", but "poses the wrong answers". Nikolai Berdyaev wrote that he may have influenced the Eurasianists' acceptance of the Revolution as a fact, but he noted that a number of key Eurasianist tenets were completely alien and hostile to him: they did not love freedom as he did, they were statists, they were hostile to Western culture in a way Berdyaev was not, and they accepted Orthodoxy in a perfunctory manner.[6]

In October 1925 a congress was held in Prague with the intention of creating a seminar.[1] One of the participants was Vladimir Nikolaevich Ilyin (1890-1974), a philosopher, theologian and composer from Kyiv and not related to Ivan A. Ilyin who has been presented in the literature by various authors as belonging to the group.[1][7]

Several members of the Eurasianists were affected by the Soviet provocational TREST operation, which had set up a fake meeting of Eurasianists in Russia that was attended by the Eurasianist leader P.N. Savitsky in 1926 (an earlier series of trips were also made two years earlier by Eurasianist member P. Arapov). The uncovering of the TREST as a Soviet provocation caused a serious morale blow to the Eurasianists and discredited their public image.[8]

In the late 1920s, Eurasianists polarized and became divided in to two groups, the left Eurasianists, who were becoming increasingly pro-Soviet and pro-communist and the classic right Eurasianists, who remained staunchly anti-communist and anti-Soviet.[9] After the emergence of "left Eurasianism" in Paris, where some of the movement's leaders became pro-Soviet, Trubetzkoy who was a staunch anti-communist heavily criticised them and eventually broke with the Eurasianist movement.[10] The Eurasianists faded quickly from the Russian émigré community; also V.N. Ilyin left.[11][12] By 1929, the Eurasianists had ceased publishing their periodical. Several organizations similar in spirit to the Eurasianists sprung up in the emigre community at around the same time, such as the pro-Monarchist Mladorossi and the Smenovekhovtsi.

During the mid 1930s, representatives of the Eurasianist movement who had settled in the Soviet Union were suppressed during the Stalinist purges and émigré Eurasianists had mostly scattered throughout Europe. By 1938, any organized Eurasianist movement had ceased to exist.[8][13]

Early proponents of Eurasianism in the West argued that control of the Eurasian heartland was the key to geopolitical dominance.[14] It influenced Oswald Spengler, and on the extreme right, the American white nationalist and neo-Nazi Francis Parker Yockey,[15] the Belgian Nazi collaborator Jean-François Thiriart and interwar German National Bolsheviks.[16]

Greater Russia

The political-cultural concept espoused by some in Russia is sometimes called the "Greater Russia" and is described as a political aspiration of pan-Russian nationalists and irredentists to retake the territories of the other republics of the former Soviet Union, territory of the former Russian Empire, the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, and amalgamate them into a single Russian state. Alexander Rutskoy, the vice president of Russia from 1991 to 1993, asserted irredentist claims to Narva in Estonia, Crimea in Ukraine , and Ust-Kamenogorsk in Kazakhstan, among other territories.[17]

Before war broke out between Russia and Georgia in 2008, Russian political theorist Aleksandr Dugin visited South Ossetia and predicted: "Our troops will occupy the Georgian capital Tbilisi, the entire country, and perhaps even Ukraine and the Crimean Peninsula, which is historically part of Russia, anyway."[18] Former South Ossetian president Eduard Kokoity is a Eurasianist and argues that South Ossetia has never left the Russian Empire and should be part of Russia .[19]

In March 2022 American journalist Michael Hirsh wrote that Russian President Vladimir Putin is a messianic Russian nationalist and a Eurasianist "whose constant invocation of history going back to Kievan Rus, however specious, is the best explanation for his view that Ukraine must be part of Russia’s sphere of influence".[20]

Eurasianism as ideology

For David Lewis, there are a number of people who assert "an alternative topography, articulated in a series of spatial projects – the ‘Russian World’, ‘Eurasian integration’, ‘Greater Eurasia’ – which aims to carve out a space in opposition to the ‘spacelessness’ of Western-dominated global order. Influential Russian foreign policy thinkers view the emerging twenty-first-century international order as being constituted not by institutions of global governance, but by a few major political-economic regions, dominated by major powers, a return to the sphere-of-influence politics of the past. It is Russia’s goal [say these thinkers] to assert its own central role as a great power, in just such a ‘Great Space’, that of Eurasia.[21]

The head of the Russian Foreign Ministry's school for future diplomats, Igor Panarin, is a vocal Eurasianist, as is the head of the Faculty of World Economy and International Affairs at the Moscow Higher School of Economics, Sergey Karaganov.

Academics such as Nataliia Narochnitskaia, Egor Kholmogorov, and Vadim Tsymburskii all espouse a messianic version of Eurasianism, and twin it with some form of Eastern Orthodox Church theology.[22][23]

An exponent of neo-Eurasianism is the Russian political theorist Alexander Dugin, who initially followed the ideology of National Bolshevism. He brought into Eurasianism the idea of a "third position" (a combination of capitalism and socialism), geopolitics (Eurasianism as a tellurocracy, opposing the Atlantic Anglo-Saxon thalassocracy of the USA and NATO) and Stalinist Russian conservatism (the USSR as a major Eurasian power). In Dugin's works, Eurasian concepts and provisions are intertwined with the concepts of European New Right. Researchers note that in the formulation of philosophical problems and political projects, he significantly deviates from classical Eurasianism, which is presented in his numerous works very selectively, eclectically. In the neo-Eurasianism of Dugin's version, the Russian ethnos is considered "the most priority Eurasian ethnos", which must fulfill the civilizational mission of forming a Eurasian empire that will occupy the entire continent. The main threat is declared by the United States and the Anglo-Saxon world in general under a "neo-liberal" ideology he calls "Atlanticism". The most preferred form of government is a Russian fascist dictatorship and a totalitarian state with complete ideological control over society. In the 1990s, Dugin criticized Italian fascism and German Nazism as "not enough fascist", and accused China of anti-Russian subversion. In subsequent years he abandoned direct apology for fascism and prefers to speak from the positions of the conservative revolution and National Bolshevism, which, however, researchers also refer to varieties of fascism called the Fourth Position.[citation needed]

Criticism

Political scientist Anton Shekhovtsov defines Dugin's version of Neo-Eurasianism as "a form of a fascist ideology centred on the idea of revolutionising the Russian society and building a totalitarian, Russia-dominated Eurasian Empire that would challenge and eventually defeat its eternal adversary represented by the United States and its Atlanticist allies, thus bringing about a new ‘golden age’ of global political and cultural illiberalism".[24]

Australian russologist Paul Dibb identifies Putin, supported by Panarin, Karaganov and Dugin, as having "begun to stress the geopolitics of what they call ‘Eurasianism’, which is an intellectual movement promoting an ideology of Russian–Asian greatness." In this context, a westernized Ukraine would be in the words of Karaganov "a spearhead aimed at the heart of Russia".[25] Eurasianism would seem negatively to impact the Baltic countries,[26] as well as Poland .[22]

Igor Torbakov argued in June 2022 that "According to the Kremlin’s geopolitical outlook, Russia could only successfully compete with the United States, China or the European Union if it acts as a leader of the regional bloc. Bringing Russia and its ex-Soviet neighbours into a closely integrated community of states, Russian strategists contend, would allow this Eurasian association to become one of the major centres of global and regional governance."[27]

According to Clover, Eurasianism appeared to be all the rage in early 21st-century Russia. One commentator noted that during Putin’s later years, it was "one of the best known and most frequently mentioned political movements of the period."[28]

Pragmatic Eurasianism

Ideologically, President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev’s speech in March 1994 at Moscow State University became the starting point for the implementation of a pragmatic Eurasianism. He proposed an integration paradigm that was fundamentally new at the time: to move towards a Eurasian Union based on economic integration and common defense.[29] This vision has been later materialized in the Eurasian Economic Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization. Eurasianism in Nazarbayev’s reading is seen as a system of foreign policy, economic ideas and priorities (as opposed to a philosophy). This type of Eurasianism is unequivocally open to the outside world.

Eurasian Economic Union

The Eurasian Economic Union was founded in January 2015, consisting of Armenia, Belarus , Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and observer members Moldova, Uzbekistan and Cuba, all of them (except Cuba) being previous members of the Soviet Union. Members include states from both Europe and Asia; the union promotes political and economic cooperation among members.

Collective Security Treaty Organization

The Collective Security Treaty Organization is an intergovernmental military alliance that was signed on 15 May 1992. In 1992, six post-Soviet states belonging to the Commonwealth of Independent States—Russia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan—signed the Collective Security Treaty (also referred to as the "Tashkent Pact" or "Tashkent Treaty").[30] Three other post-Soviet states—Azerbaijan, Belarus , and Georgia—signed the next year and the treaty took effect in 1994. Five years later, six of the nine—all but Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Uzbekistan—agreed to renew the treaty for five more years, and in 2002 those six agreed to create the Collective Security Treaty Organization as a military alliance. Uzbekistan rejoined the CSTO in 2006 but withdrew in 2012.

Turkey

Since the late 1990s, Eurasianism has gained some following in Turkey among neo-nationalist (ulusalcı) circles. The most prominent figure who is associated with Dugin is Doğu Perinçek, the leader of the Patriotic Party (Vatan Partisi).[31]

In literature

In the future time depicted in George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty Four, the Soviet Union has mutated into Eurasia, one of the three superstates dominating the world.

Similarly, Robert Heinlein's story "Solution Unsatisfactory" depicts a future in which the Soviet Union would be transformed into "The Eurasian Union".

See also

- All-Russian nation

- Eurasian Economic Union

- Eurasian Observatory for Democracy and Elections

- Eurasian Youth Union

- Intermediate Region

- Manifest destiny

- Proletarian internationalism

- Great Game

- Atlanticism

- Neo-Sovietism

- Nostalgia for the Soviet Union

- Rashism

- Russian irredentism

- Russian nationalism

- Conservatism in Russia

- Pan-nationalism

- Pan-Slavism

- Post-Soviet states

- Territorial evolution of Russia

- Belt and Road Initiative

- Lev Gumilyov

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Böss, Otto (January 14, 1961). "Die Lehre der Eurasier: ein Beitrag zur russischen Ideengeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts". Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. https://books.google.com/books?id=F-lSPuoXuNUC&q=Il%27in&pg=PA7.

- ↑ "Transcript: Russian Nationalism". 8 March 2019. https://srbpodcast.org/2019/03/08/transcript-russian-nationalism/.

- ↑ "Re-imagining World Spaces: The New Relevance of Eurasia". 31 July 2016. https://humanitiesfutures.org/papers/re-imagining-world-spaces-new-relevance-eurasia/.

- ↑ Marlène Laruelle (2008) Russian Eurasianism: An Ideology of Empire. Woodrow Wilson Center Press

- ↑ "The Jewish Eurasianism of Yakov Bromberg". http://stephenshenfield.net/themes/jewish-issues/jews-in-tsarist-russia/105-the-jewish-eurasianism-of-yakov-bromberg.

- ↑ Berdyaev, Samopoznanie. Web: http://yakov.works/library/02_b/berdyaev/1940_39_10.htm

- ↑ "ИЛЬИН". https://www.pravenc.ru/text/389449.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Алпатов, В. М.; Ашнин, Ф. Д. (1996). "Евразийство в зеркале ОГПУ-НКВД-КГБ" (in ru). Вестник Евразии=Acta Eurasica 2 (3): 5–18. https://istina.ipmnet.ru/publications/article/5597401/.

- ↑ "Николай Смирнов. Левое евразийство и постколониальная теория" (in en). https://syg.ma/@geograf-smirnoff/lievoie-ievraziistvo-i-postkolonialnaia-tieoriia.

- ↑ "Николай Смирнов. Левое евразийство и постколониальная теория" (in ru). https://syg.ma/@geograf-smirnoff/lievoie-ievraziistvo-i-postkolonialnaia-tieoriia.

- ↑ "Иван Ильин: Война учит нас жить, любя нечто высшее · Родина на Неве". 3 August 2022. https://rodinananeve.ru/ivan-ilyin-voyna-uchit-nas-jit-lubia-nechto-visshee/.

- ↑ "Ильин Владимир Николаевич: Русская философия : Руниверс". https://runivers.ru/philosophy/lib/authors/author154634/.

- ↑ "ЕВРАЗИЙСТВО • Большая российская энциклопедия - электронная версия". https://bigenc.ru/philosophy/text/1973841.

- ↑ Rose, Matthew (2021). A World after Liberalism: Philosophers of the Radical Right. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300263084. https://books.google.com/books?id=NSA3EAAAQBAJ. p. 80

- ↑ Mulhall, Joe (2020). British Fascism After the Holocaust: From the Birth of Denial to the Notting Hill Riots 1939–1958. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780429840258. https://books.google.com/books?id=8i34DwAAQBAJ&q=British+Fascism+After+the+Holocaust:+From+the+Birth+of+Denial+to+the+Notting+Hill+Riots+1939%E2%80%931958. p. 114

- ↑ Allensworth, Wayne (1998). The Russian Question: Nationalism, Modernization and Post-Communist Russia. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. p. 251.

- ↑ Chapman, Thomas; Roeder, Philip G. (November 2007). "Partition as a Solution to Wars of Nationalism: The Importance of Institutions". American Political Science Review 101 (4): 680. doi:10.1017/s0003055407070438.

- ↑ "Road to War in Georgia: The Chronicle of a Caucasian Tragedy", Spiegel, August 25, 2008.

- ↑ Neo-Eurasianist Aleksandr Dugin on the Russia-Georgia Conflict, CACI Analyst, September 3, 2008.

- ↑ "Putin's Thousand-Year War". Foreign Policy. 12 March 2022. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/12/putins-thousand-year-war/.

- ↑ Lewis, David G. (2020-03-01). Russia's New Authoritarianism. doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9781474454766.001.0001. ISBN 9781474454766. http://dx.doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9781474454766.001.0001.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Kushnir, Ostap (March 2019). "Messianic Narrations in Contemporary Russian Statecraft and Foreign Policy". Central European Journal of International and Security Studies 13 (1): 37–62. doi:10.51870/CEJISS.A130108. https://www.cejiss.org/messianic-narrations-in-contemporary-russian-statecraft-and-foreign-policy.

- ↑ Freeze, Gregory L. "Recent Scholarship on Russian Orthodoxy: A Critique." Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 2#2 (2008): 269–78.

- ↑ Shekhovtsov, Anton (2018) Russia and the Western Far Right: Tango Noir, Abingdon, Routledge, p. 43.

- ↑ Dibb, Paul (7 September 2022). "The geopolitical implications of Russia's invasion of Ukraine". Australian Strategic Policy Institute. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/geopolitical-implications-russias-invasion-ukraine.

- ↑ Sazonov, Vladimir; Ploom, Illimar; Veebel, Viljar (May 2022). "The Kremlin's Information Influence Campaigns in Estonia and Estonian Response in the Context of Russian-Western Relations". TalTech Journal of European Studies 12 (1): 27–59. doi:10.2478/bjes-2022-0002.

- ↑ Torbakov, Igor (11 July 2022). "No empire without end". Eurozine. https://www.eurozine.com/no-empire-without-end/.

- ↑ Torbakov, Igor (2019). "2". in Bernsand, Niklas; Törnquist-Plewa, Barbara (in en). 'Middle Continent' or 'Island Russia': Eurasianist Legacy and Vadim Tsymburskii's Revisionist Geopolitics. 11. Cultural and Political Imaginaries in Putin’s Russia: Brill. pp. 37–62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvbqs855.6.

- ↑ Nazarbayev, Nursultan (1997). "Eurasian Union: Ideas, Practice, Perspectives 1994-1997" (in ru). Moscow: Fund for cooperation and development in social and political science. pp. 480. https://presidentlibrary.kz/en/node/908.

- ↑ ed, Alexei G. Arbatov ... (1999). Russia and the West : the 21st century security environment. Armonk, NY [u.a.]: Sharpe. p. 62. ISBN 978-0765604323. https://books.google.com/books?id=rHYZk-t7dI0C&pg=PA62. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ Mehmet Ulusoy: "Rusya, Dugin ve‚ Türkiye’nin Avrasyacılık stratejisi" Aydınlık Dec. 5 2004, pp. 10–16

Sources

- The Mission of Russian Emigration, M.V. Nazarov. Moscow: Rodnik, 1994. ISBN 5-86231-172-6

- Russia Abroad: A comprehensive guide to Russian Emigration after 1917 also some Ustrialov's papers in the Library

- The criticism towards the West and the future of Russia-Eurasia

- Laruelle, Marlene, ed (2015). Eurasianism and the European Far Right: Reshaping the Europe–Russia Relationship. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-1068-4.

- Stefan Wiederkehr, Die eurasische Bewegung. Wissenschaft und Politik in der russischen Emigration der Zwischenkriegszeit und im postsowjetischen Russland (Köln u.a., Böhlau 2007) (Beiträge zur Geschichte Osteuropas, 39).

External links

- The Fourth Political Theory – Eurasianism

- Evrazia

- Geopolitika.ru

- GraNews.info

- Eurasianist-Archive.com