Earth:Lake Parime

| Lake Parime | |

|---|---|

| Lake Parima, Parime Lacus | |

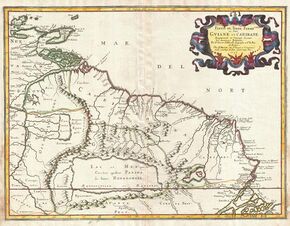

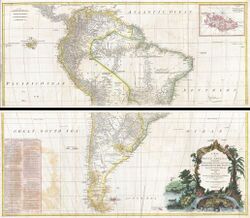

Nicolas Sanson's 1656 map showing the "lake or sea called by the Caribes, Parime, by the Iaoyi, Roponowini." Manoa or El Dorado is located on the northwest corner of the lake. To the north is Lake Cassipa. | |

| Location | Northeastern South America (various locations proposed) |

| Type | Mythical |

| River sources | Parime River, Takutu River, Orinoco |

| Max. length | 400 km (250 mi) |

| Max. width | 80 km (50 mi) |

| Surface area | 80,000 km2 (31,000 sq mi) |

| Max. depth | 120 m (390 ft) |

| Settlements | Manoa, El Dorado |

Lake Parime or Lake Parima is a legendary lake located in South America. It was reputedly the location of the fabled city of El Dorado, also known as Manoa, much sought-after by European explorers. Repeated attempts to find the lake failed to confirm its existence, and it was dismissed as a myth along with the city. The search for Lake Parime led explorers to map the rivers and other features of southern Venezuela, northern Brazil, and southwestern Guyana before the lake's existence was definitively disproved in the early 19th century. Some explorers proposed that the seasonal flooding of the Rupununi savannah may have been misidentified as a lake. Recent geological investigations suggest that a lake may have existed in northern Brazil, but that it dried up some time in the 18th century. Both "Manoa" (Arawak language) and "Parime" (Carib language) are believed to mean "big lake".[1][2]

Two other mythical lakes, Lake Xarayes or Xaraies[3][4] (sometimes called Lake Eupana),[5][6] and Lake Cassipa,[1][7] are often depicted on early maps of South America.

First attempts at discovery

Walter Raleigh, 1595

Sir Walter Raleigh began the exploration of the Guianas in earnest in 1594 and described the city of Manoa, which he believed to be the legendary city of El Dorado, as being located on Lake Parime far up the Orinoco River in Venezuela.[8] Much of his exploration is documented in his books The Discoverie of the Large, Rich, and Bewtiful Empyre of Guiana,[7] published first in 1596, and The Discovery of Guiana, and the Journal of the Second Voyage Thereto, published in 1606.[9] How much of Raleigh's work is true and how much is fabricated remains unclear:[10] His account indicates that he only succeeded in navigating up the Orinoco as far as Angostura, (what is now Ciudad Bolívar) and did not come close to the supposed location of Lake Parime.[11] Raleigh says of the lake:

I have been assured by such of the Spaniards as have seen Manoa, the imperial city of Guiana, which the Spaniards call El Dorado, that for the greatness, for the riches, and for the excellent seat, it far exceedeth any of the world, at least of so much of the world as is known to the Spanish nation. It is founded upon a lake of salt water of 200 leagues long, like unto Mare Caspium.[7]

According to Raleigh, the lake itself was the source of the gold possessed by the people of Manoa:

Most of the gold which they made in plates and images was not severed from the stone, but on the lake of Manoa, and in a multitude of other rivers, they gathered it in grains of perfect gold and in pieces as big as small stones.[7]

Lawrence Kemys, 1596

In 1596 Raleigh sent his lieutenant, Lawrence Kemys, back to Guyana in the area of the Orinoco River, to gather more information about the lake and the golden city.[12] During his exploration of the coast between the Amazon and the Orinoco, Kemys mapped the location of Amerindian tribes and prepared geographical, geological and botanical reports of the country. Kemys described the coast of Guiana in detail in his Relation of the Second Voyage to Guiana (1596)[13] and says that indigenous people of Guiana traveled inland by canoe and land passages towards a large body of water on the shores of which he supposed was located Manoa, Golden City of El Dorado. One of these rivers leading south into the interior of Guiana was the Essequibo.[14] Kemys wrote that the Indians called this river "brother of the Orenoque [Orinoco]" and that this river of Essequibo, or Devoritia,

lyeth Southerly into the land, and from the mouth of it unto the head, they pass in twenty days: then taking their provision they carry it on their shoulders one days journey: afterwards they return for their canoas, and bear them likewise to the side of a lake, which the Iaos call Roponowini, the Charibes, Parime: which is of such bigness, that they know no difference between it and the main sea. There be infinite numbers of canoas in this lake, and (as I suppose) it is no other than that, whereon Manoa standeth.[15]

Early maps

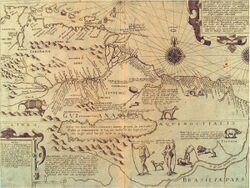

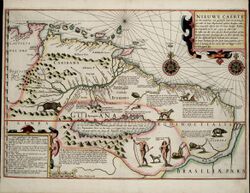

thumb|right|1621 map by Willem Blaeu showing Lake Parime straddling the equator, with "Manoa al Dorada" on the north shore, just below Lake Cassipa. thumb|Parime Lacus on a map by Hessel Gerritsz (1625). "Manoa, o el Dorado", appears on the northwestern corner of the lake.

As a result of Raleigh's work, maps began to appear depicting El Dorado and Lake Parime. One of the first was the elder Jodocus Hondius' Nieuwe Caerte van het Wonderbaer ende Goudrycke Landt Guiana, which was published in 1598. Hondius' map depicts an elongated Lake Parime south of the Orinoco River, with the majority of the lake positioned south of the equator, and with Manoa on the northern shore, towards the eastern half of the lake. Manoa is noted as "the greatest city in the entire world". Hondius' map was subsequently copied by Theodore de Bry and published in his popular Grands Voyages in 1599.[16] When Hondius published a completely revised edition of Mercator's Atlas in 1608,[17] it included a map of South America featuring Lake Parime with the majority of the lake located south of the equator, and with Manoa again along the northern shore, although not quite so far east.[18]

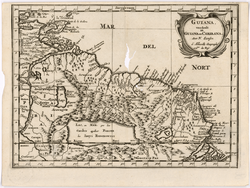

Cartographer Guillaume Delisle was among the first to cast doubts on the lake's existence. In a map of Guyana printed in 1730, he included an outline of the lake, then replaced it with the notation: "It is in these regions that most authors place the Lake Parime and the City of Manoa of El Dorado."[19][20] Delisle reluctantly included a lake in southwestern Guyana on several subsequent maps, but did not name it or the city of Manoa.[21]

The lake was printed on maps throughout the 17th and 18th centuries and up until the early 19th century. Some cartographers and naturalists moved the lake more to the southeast of the Orinoco River and north of the Amazon river, often situating it south of the mountains that border Venezuela, Guiana, and Brazil . However, by the late 18th century, failure to confirm the lake's existence led to its removal from most maps.[22] A 1792 map of the Rio Branco by José Joaquin Freire shows no sign of a lake, although there is now a Parimé River.[23]

17th century explorations

Thomas Roe, 1611

In early 1611 Sir Thomas Roe, on a mission to the West Indies for Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, sailed his 200-ton ship, the Lion's Claw, some 320 kilometres (200 mi) up the Amazon,[24] then took a party of canoes up the Oyapock River in search of Lake Parime, negotiating thirty-two rapids and traveling about 160 km (100 mi) before they ran out of food and had to turn back.[25][26][27][28]

Raleigh and Kemys, 1617

In March 1617, Raleigh and Kemys returned to Venezuela in search of Lake Parime and El Dorado. The expedition failed to uncover any new evidence of the lake and ended with the death of Raleigh's son Walter and the suicide of Captain Kemys.[29]

Samuel Fritz, 1689

Between 1689 and 1691 the Jesuit priest Samuel Fritz traveled along the Amazon and its tributaries, preparing a detailed map at the request of the Royal Audiencia of Quito.[30] Fritz was skeptical of the existence of a golden city, but thought that Lake Parime probably did exist, and included it prominently in his map.[31][32]

18th century explorations

Nicholas Horstman, 1739

In November 1739, Nicholas Horstman (sometimes spelled "Hortsman"), a surgeon from Hildesheim, Germany who was secretly commissioned by the Dutch Governor of Guiana (Laurens Storm van 's Gravesande), traveled up the Essequibo River accompanied by two Dutch soldiers and four Indian guides.[33] In April 1741 one of the Indian guides returned reporting that in 1740 Horstman had crossed over to the Rio Branco and descended it to its confluence with the Rio Negro. Rumors at the time held that Horstman had planted the Dutch Flag on the shores of Lake Parime, however later explorers determined that he had in fact visited Lake Amucu on the North Rupununi. Nothing further was heard until late November, 1742 when the other guides returned, reporting that Horstman and one of the Dutch soldiers had spent four months in a village on the Pará River, where they were discovered and arrested by the Portuguese authorities, and that they had "entered into the Portuguese service". In August 1743 Charles-Marie de La Condamine met and conversed with Horstman,[34] who appeared to be living freely with the Portuguese in Pará, and Horstman gave him his fragmentary diary, titled "Journey which I made to the Imaginary Lake of Parima, or of Gold, in the Year 1739." Horstman states that on May 8, 1740,

We entered the lake, in which we spent this entire day, and the next likewise, and after having passed an island, again dragging the canoe and also the cargo, we entered the great lake, called by the Indians Amucu, in which we proceeded constantly over reeds, with which the lake is entirely filled, and it has two islands in the middle... The water is black in the lake and white in the river.[35]

Horstman also gave La Condamine a remarkably accurate hand-drawn map of his route from the coast through the interior of Northern Brazil.[34] La Condamine then gave the map to the French geographer Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville. Lake Amucu was incorporated into his Carte de l'Amerique Meridionale in 1748.[36]

Manuel Centurion, 1740

In 1740, Don Manuel Centurion, Governor of Santo Tomé de Guayana de Angostura del Orinoco in Venezuela, hearing a report from an Indian regarding Lake Parima, embarked on a journey up the Caura River and the Paragua River.[37] According to Humboldt:

Arimuicaipi, an Indian of the nation of the Ipurucotos, went down the Rio Carony, and by his false narrations inflamed the imagination of the Spanish colonists. He showed them in the southern sky the Clouds of Magellan, the whitish light of which he said was the reflection of the argentiferous rocks situate in the middle of the Laguna Parima. This was describing in a very poetical manner the splendour of the micaceous and talcy slates of his country![1]

During his expedition, "several hundred persons perished miserably" and Centurion failed to confirm the existence of either a lake or a city.[1]

Charles Marie de La Condamine, 1743

Between June and September 1743 the scientist and geographer Charles de La Condamine traveled from Quito to the Atlantic coast via the Amazon River, charting its course and making scientific observations. In his subsequent account of this journey, Abbreviated Relation of a Journey made in the Interior of South America (1745), Condamine discussed the existence of Lake Parime, stating that although the Indians had extracted "small flakes" of gold from the rivers, these stories had been greatly exaggerated to concoct the myth of a golden city:

The Manaus were neighbors of a large lake, & even several Great Lakes; because they are very frequent in a low country [which is] subject to flooding. The Manaus pulled gold from the Yquiari[38] & seized small flakes: these are real facts, which were used in exaggeration, giving rise to the fable of the city of Manoa & Golden Lake. If we find that there is still a long way from the small flakes of gold of the Manaus, to the [golden] roofs of the town of Manoa, & that there is nonetheless far from the glitter of this metal, ripped from the waters of the Yquiari, to the fable of Parime gold; one cannot deny that on the one hand greed & concern of Europeans who wanted by any force to find what they were looking for, and on the other, clever liars & exaggerating Indians [who], interested in sending away the uncomfortable visitors, might alter & deface [the facts] to the point of making them unrecognizable. The history of the discoveries of the new world provides more than one example of similar metamorphoses.[34]

During his journey La Condamine met and conversed with Nicholas Horstman and determined that he had found Lake Amucu in approximately the location of the reputed Lake Parime. On the map of his own travels included in his book, La Condamine placed a small lake as a source of the Takutu River, designating it only "Lac".[34]

19th century explorations

Humboldt and Bonpland, 1799–1803

Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland considered Lake Amucu in the North Rupununi, which had been visited by the German surgeon Nicholas Horstman, to be the Lake Parime described by Sir Walter Raleigh.[39] In his Relation historique du voyage aux régions équinoxiales du nouveau continent (1825), Humboldt indicated that Lake Amucu was in the same location as the purported Lake Parime (or Roponowini) described to Raleigh, and was also a "large inland sea" when flooded; he noted that:

All fables have some real foundation; that of El Dorado resembles those myths of antiquity ... No man in Europe believes any longer in the wealth of Guiana and the ... town of Manoa and its palaces covered with plates of massy gold have long since disappeared; but the geographical apparatus serving to adorn the fable of El Dorado, the lake Parima, which ... reflected the image of so many sumptuous edifices, has been religiously preserved by geographers.[1]

Charles Waterton, 1812

In 1812 Charles Waterton independently came to a similar conclusion and proposed that seasonal flooding of the Rupununi savannah could be the famed Lake Parime. Waterton wrote:

According to the new map of South America, Lake Parima, or the White Sea, ought to be within three or four days' walk from this place. On asking the Indians whether there was such a place or not, and describing that the water was fresh and good to drink, an old Indian, who appeared to be about sixty, said that there was such a place, and that he had been there ... [but] probably the Lake Parima they talked of was the Amazons ... In crossing the plain at the most advantageous place you are above ankle-deep in water for three hours; the remainder of the way is dry, the ground gently rising. As the lower parts of this spacious plain put on somewhat the appearance of a lake during the periodical rains, it is not improbable but that this is the place which hath given rise to the supposed existence of the famed Lake Parima, or El Dorado ... On asking the old officer if there were such a place as Lake Parima, or El Dorado, he replied, he looked upon it as imaginary altogether. "I have been above forty years," added he, "in Portuguese Guiana, but have never yet met with anybody who has seen the lake. So much for Lake Parima, or El Dorado, or the White Sea. Its existence at best seems doubtful; some affirm that there is such a place, and others deny it."[40]

Robert Schomburgk, 1840

In 1840 explorer Robert Hermann Schomburgk visited Pirara on the edge of Lake Amucu.[41][42][43] He stated that this area of flooded Rupununi which linked the Amazon and Essequibo River drainages was most likely to be the Lake Parime:[44]

The geological structure of this region leaves but little doubt that it was once the bed of an inland lake which ... broke its barrier, forcing for its waters a path to the Atlantic. May we not connect with the former existence of this inland sea the fable of the Lake Parima and the El Dorado? Thousands of years may have elapsed ... still the tradition of the Lake Parima and the El Dorado survived ... transmitted from father to son.[45]

thumb|right|[[John Pinkerton's 1818 map of northern South America, one of the last maps to show Lake Parime (here named "Lake Parima or White Sea"). The existence of Manoa or El Dorado had by now been disproved, and most other maps of this period do not show Lake Parime.]]

Jacob van Heuvel, 1844

In 1844 the American author Jacob Adrien van Heuvel, a graduate of Yale and a law student, published an account of his travels in Guiana in which he investigated evidence for the existence of El Dorado and Lake Parima. The book described a journey to Guiana he had made in 1819–20 during which he questioned a "Charibe chief" named Mahanerwa about the existence of the lake. Mahanerwa drew a map in the sand, and stated that a large body of water lay southeast of the Orinoco. Van Heuvel superimposed this drawing onto John Arrowsmith's 1840 map of British Guyana, claiming that much of this body of water, some 250 miles (400 km) in length, was likely a "temporary inundation" but that "water must fill the savannah" for half the year at least and probably more. Van Heuvel considered Lake Parima and Lake Cassipa to be identical.[46]

In his 1848 edition of Raleigh's The Discovery of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana, Schomburgk dismissed Van Heuvel's propositions:

Mr. Van Heuvel visited the coast regions of Guiana without penetrating into the interior, and his conclusions respecting this lake rest only upon what he learned from some Indians, whose language he did not understand, and upon the maps of Sanson, D'Anville and others of the last century; and although fully acquainted with Humboldt's writings, "who," he says, "effaced without sufficient grounds that wondrous lake," Mr. Van Heuvel has fully restored it, and gives to it a length of from two hundred to two hundred and fifty miles, and a breadth of about fifty miles. Out of it flow the rivers Parima and Takutu into the Rio Negro and the Amazon; the Cuyuni, the Siparuni, and the Mazaruni, into the Essequibo; and the Paragua into the Orinoco. A single step backwards in our geographical knowledge is much to be regretted, and all who take interest in that science ought to aid in preventing the dissemination of such absurdities.[11][47]

In spite of well-publicized evidence disproving the existence of Lake Parime, the 1853 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica described the lake under the entry for "America:"

[Lake Titicaca] and the Lake Parimé in Guiana are the only sheets of fresh water in South America which vie in magnitude with those of the St. Lawrence ... The Cordillera of Parimé incloses amongst its ridges the great Lake Parimé, in longitude 60°, and several others of smaller size.[48]

Evidence for an ancient lake

Nhamini-wi and the Lake of Milk

The Tucano and Piratapuia tribes of the upper Rio Negro tell a story of the Nhamini-wi (the "narrow path"). The Nhamini-wi was a pre-Columbian road that traveled from the mountains in the west where the "house of the night" was located.[49] The trail began at axpeko-dixtara, or the "lake of milk"[Note 1] in the east. In 1977 artist and explorer Roland Stevenson found ruins north of the Rio Negro in the Uaupés River basin that are believed to be the remnants of the Nhamini-wi.[51] Led by indigenous guides Stevenson found old and collapsed stone walls that were dotted every twenty kilometers along an east-to-west line.

Stevenson followed the vestiges of the road eastward to find the lake and ended up in Roraima, Brazil , in the plains of Boa Vista. Upon examining the region Brazilian geologists Gert Woeltje and Frederico Guimarães Cruz along with Roland Stevenson[52] found that on all the surrounding hillsides a horizontal line appears at a uniform level approximately 120 metres (390 ft) above sea level.[49] This line registers the water level of an extinct lake which existed until relatively recent times. Researchers who studied it found that the lake's previous diameter measured 400 kilometres (250 mi) and its area was about 80,000 square kilometres (31,000 sq mi). About 700 years ago this giant lake began to drain due to epeirogenic movement.[53] In June 1690, a massive earthquake opened a bedrock fault, forming a rift or a graben that permitted the water to flow into the Rio Branco.[54] By the early 19th century it had dried up completely.[55]

Geological evidence

Geologic research suggests that, thousands of years ago, conditions existed for the formation of a lake. Sedimentary rock in this region, known as the Takutu Basin or the Takutu Formation, dates back to the late Paleozoic,[56] roughly 250 million years ago, and the basin connected with the Atlantic via the Takutu Graben.[57] The geologic history of the Takutu Graben is characterized by one phase of volcanic activity and three depositional phases of sedimentary rocks. Rifting (due to divergent tectonic plate movements) occurred in a lake or delta environment in the Late Triassic to Early Jurassic periods, between 200 million and one hundred and fifty million years ago.[58] Starting around 66,000 years ago, sea level rise and more humid conditions created flooded zones north of the confluence of the Rio Negro and the Solimões River, in what is now Roraima.[59]

Seasonal flooding was probably misidentified as a lake by some observers. The drainage system of the Rupununi Savannahs is unable to carry a high volume of surface runoff and as a result, most rivers flood in the wet season. In a few places ground water drainage is impeded by clay, and ponds and lakes persist for several months.[60]

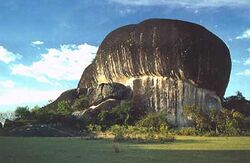

Archeological evidence: Pedra Pintada

Roraima's well-known Pedra Pintada is the site of numerous pictograms and petroglyphs dating to between 9000 and 12000 years ago[61] or less than 4000 years ago.[62] Designs 10 metres (33 ft) above the ground on the sheer exterior face of the rock were probably painted by people standing in canoes on the surface of the now-vanished lake.[63][64] Gold, which was reported to be washed up on the shores of the lake, was most likely carried by streams and rivers out of the mountains where it can be found today.[65]

Additional maps

- Map from 1626 by John Speed showing Lake Parime, Lake Cassipa and Lake Eupana

- Map from 1635 by Willem Blaeu

- Map from 1652 by Nicolas Sanson showing "Lac ou Mer de Parime" and the city of El Dorado on the western shore

- Map from 1690 by Vincenzo Coronelli which mentions "La Città del Manoa del Dorado" and shows Lake Cassipa and Lake Xarayes

- Map from 1707 by Samuel Fritz

- Map from 1750 by Emanuel Bowen showing Lake Parima and the city of Manoa

- Map from 1751 by Giovanni Petroschi and Carolo Brentano, showing "Parime Lacus, ab auri opulentia fabulosus".

- Map from 1796 by Francisco Requena

- Map from 1807 by William Faden which shows the "Golden Lake or Lake Parime, called likewise Parana Pitinga i.e. White Sea, on the Banks of which the Discoverers of the 16th century did place the Imaginary city of Manoa del Dorado".[22]

- Map from 1840 by Robert Schomburgk showing Lake Amucu

Notes

- ↑ So-called because of inorganic sediments carried by the river.[50] Alfred Russel Wallace mentions this peculiar coloration in "On the Rio Negro," a paper read at the 13 June 1853 meeting of the Royal Geographical Society, in which he says: "[The Rio Branco] is white to a remarkable degree, its waters being actually milky in appearance." Humboldt attributed the color to the presence of silicates in the water, principally mica and talc.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Alexander von Humboldt, Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America During the Years 1799–1804, (chapter 25). Henry G. Bohn, London, 1853.

- ↑ Catherine Alès, Michel Pouyllau, "La Conquête de l'inutile. Les géographies imaginaires de l'Eldorado," (in French) Homme, Année 1992:122-124 pp. 271-308.

- ↑ Laguna de los Xarayes in Rare Maps

- ↑ Hermann Moll, Map of Uruguay, Paraguay, Southern Brazil and Northern Argentina (El Dorado), 1701

- ↑ Jodocus Hondius, America Meridionalis, 1620

- ↑ John Speed, Map of America, 1626

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Sir Walter Raleigh, The Discoverie of the Large, Rich, and Bewtiful Empyre of Guiana (1596; repr., Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1968)

- ↑ Marc Aronson, Sir Walter Ralegh and the Quest for El Dorado, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2000. ISBN 039584827X

- ↑ Sir Walter Raleigh, The Discovery of Guiana, and the Journal of the Second Voyage Thereto (1606; repr., London: Cassell, 1887)

- ↑ Paul R. Sellin, Treasure, Treason and the Tower: El Dorado and the Murder of Sir Walter Raleigh. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Robert H. Schomburgk, The Discovery of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana: With a Relation of the Great and Golden City of Manoa... Etc. Performed in the Year 1595, by Sir W. Ralegh, Knt... Reprinted from the Edition of 1596, with Some Unpublished Documents Relative to that Country. Ed., with Copious Explanatory Notes and a Biographical Memoir, Hakluyt Society, 1848.

- ↑ "Raleigh's Second Expedition to Guiana."

- ↑ John Knox Laughton, "Kemys, Lawrence" Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900, Volume 30.

- ↑ Renzo Duin, Wayana Socio-Political Landscapes: Multi-Scalar Regionality and Temporality in Guiana, doctoral dissertation, University of Florida: Gainesville; 2009.

- ↑ Lawrence Keymis, A Relation of the Second Voyage to Guiana, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1596.

- ↑ Theodore de Bry, "The map of 'the powerful and gold-bearing kingdom of Guiana", 1599.

- ↑ Jodocus Hondius, "Typus Orbis Terrarum", Amsterdam, 1608.

- ↑ "Eliane Dotson, Lake Parime and the Golden City".

- ↑ Original French: "C'est dans ces quartiers que la pluspart des autheurs placent le Lac de Parime et la Ville de Manoa del Dorado."

- ↑ Renzo Duin, Wayana Socio-Political Landscapes: Multi-Scalar Regionality and Temporality in Guiana PhD dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville, 2009; p. 70.

- ↑ Guillaume De L'Isle and Philippe Buache: Carte D'Amerique Dressee pour l'usage du Roy en 1722...Et augmentee desa Nouvelles Decovertes en 1763.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Justin Winsor, Spanish Explorations and Settlements in North America from the Fifteenth to the Seventeenth Century: Volume 2 of Narrative and critical history of America, Houghton, Mifflin, 1886; p. 589.

- ↑ Jose Joaquin Freire, "Map of the Branco or Parimé River and of the Caratirimani, Uararicapará, Majari, Tacutú and Mahú Rivers," 1792

- ↑ Alírio Cardoso, "The conquest of Maranhão and Atlantic disputes in the geopolitics of the Iberian Union (1596–1626)," Rev. Bras. Hist. vol.31 no.61, São Paulo, 2011.

- ↑ James Seay Dean, Tropics Bound: Elizabeth's Seadogs on the Spanish Main, The History Press, 2013. ISBN 0752496689

- ↑ James Alexander Williamson, English colonies in Guiana and on the Amazon, 1604–1668, Oxford, 1923; p. 54.

- ↑ Stanley Lane-Poole, "Roe, Thomas"; Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900, Volume 49

- ↑ Michael J. Brown, Itinerant Ambassador: The Life of Sir Thomas Roe, University Press of Kentucky, 2015; p. 15. ISBN 0813162270

- ↑ "Sir Walter Raleigh," NNDB Database

- ↑ John Hemming, Red Gold: The Conquest of the Brazilian Indians, 1500–1760, Harvard University Press, 1978. ISBN 0674751078

- ↑ Samuel Fritz, Journal of the Travels and Labours of Father Samuel Fritz in the River of the Amazons Between 1686 and 1723, edited by George Edmundson; Issue 51 of Works issued by the Hakluyt Society, ISSN 0072-9396; Hakluyt Society, 1922.

- ↑ Jesuit Camila Loureiro Dias, "Maps and Political Discourse: The Amazon River of Father Samuel Fritz," The Americas, Volume 69, Number 1, July 2012, pp. 95–116.

- ↑ C. A. Harris and John Abraham Jacob De Villiers, Storm Van's Gravesande: The Rise of British Guiana, Compiled from his Works, Hakluyt Society, 1911; University of Michigan.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Charles Marie de La Condamine, Relation abrégée d'un voyage fait dans l'intérieur de l'Amérique méridionale: depuis la côte de la mer du Sud, jusqu'aux côtes du Brésil et de la Guyane, en descendant la rivière des Amazones..., Jean-Edme Dufour and Philippe Roux, 1778; University of Lausanne [French]

- ↑ Sir Robert Hermann Schomburgk, "Lettre de N. Horstman à M. La Condamine", Great Britain, Edmond Herbert Hills, ed. Imprimé au Foreign office, par Harrison and sons, 1903 – Brazil.

- ↑ Neldson Marcolin, "Mapa feito na França em 1748 delineou novas fronteiras do Brasil continental depois do Tratado de Tordesilhas", Espelhos do Mundo, Ed. 225, Nov. 2014. [Portuguese]

- ↑ Edward M. Pierce, The Cottage Cyclopedia of History and Biography: A Copious Dictionary of Memorable Persons, Events, Places and Things, with Notices of the Present State of the Principal Countries and Nations of the Known World, and a Chronological View of American History, Case, Lockwood, 1867, Harvard University

- ↑ Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, Issue 1, Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, 1856. [Portuguese]

- ↑ Graham Watkins, Pete Oxford, and Reneé Bish, "Raleigh's El Dorado", from Rupununi: Rediscovering a Lost World, Earth in Focus Editions, 2010

- ↑ Charles Waterton, Wanderings in South America, Cassell & Co, Ltd: London, Paris & Melbourne. 1891.

- ↑ Robert Hermann Schomburgk, "Sources of the Takutu in British Guiana, in the year 1842", Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol. 13, pp 18–75, 1843

- ↑ Peter Rivière, ed. The Guiana Travels of Robert Schomburgk, 1835–1844: Explorations on behalf of the Royal Geographical Society, 1835–1839, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006; p. 274. ISBN 0904180867

- ↑ Robert Hermann Schomburgk, "Pirara and Lake Amucu, The Site of Eldorado", printed by Georges Barnard, from Twelve Views in the Interior of Guiana, 1840.

- ↑ Graham Watkins, Pete Oxford, and Reneé Bish. Rupununi: Rediscovering a Lost World, Earth in Focus Editions; November 1, 2010]. ISBN 0984168648.

- ↑ Robert Hermann Schomburgk, A Description of British Guiana, Geographical and Statistical, Surpkin, 1840; p. 6.

- ↑ Jacob Adrien Van Heuvel, El Dorado: Being a Narrative of the Circumstances which Gave Rise to Reports, in the Sixteenth Century, of the Existence of a Rich and Splendid City in South America, to which that Name was Given, and which Led to Many Enterprises in Search of it; Including a Defence of Sir Walter Raleigh, in Regard to the Relations Made by Him Respecting It, and a Nation of Female Warriors, in the Vicinity of the Amazon, in the Narrative of His Expedition to the Oronoke in 1595, J. Winchester, 1844.

- ↑ D. Graham Burnett, Masters of All They Surveyed: Exploration, Geography, and a British El Dorado The Heritage of Sociology Series; University of Chicago Press, 2001.] ISBN 0226081214

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Volume 2: A – Ana". 8th Edition. A & C Black, 1853; pp. 669–670.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Dalton Delfini Maziero, "El Dorado Em busca dos antigos mistérios Amazônicos," Arqueologiamericana. [Portuguese]

- ↑ "Comparison between white and black waters". http://www.amazonian-fish.co.uk/indexc30.html.

- ↑ Roland Stevenson, Uma Luz nos Mistérios Amazônicos. Manaus: SUFRAMA, 1994. [Portuguese]

- ↑ Roland Stevenson, "Parime: Finding the Legendary Lake."

- ↑ Jeff Shea, The March 2013 Paragua River Expedition: Penetration into The Meseta de Ichún of Venezuela, Explorers Club Report #60.

- ↑ Veloso, Alberto V. (September 2014). "On the footprints of a major Brazilian Amazon earthquake". An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. (Rio de Janeiro) 86 (3): 1115–1129. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201420130340.

- ↑ Shea, Jeff (March 2013). "The March 2013 Paragua River Expedition: Penetration into The Meseta de Ichún of Venezuela". Explorers Club Report #60. pp. 110. https://explorers.org/pdf/SHEA_FLAG_REPORT_V35-C_013014.pdf.

- ↑ A. J. Pedreira et al, (2003), "Bacias Sedimentares Paleozóicas e Meso-Cenozóicas Interiores," (Paleozoic and Meso-Cenozoic Sedimentary Basins) in Geologia, Tectônica e Recursos Minerais do Brasil. A. Bizzi, C. Schobbenhaus, R. M. Vidotti e J. H. Gonçalves (eds.) CPRM, Brasília, 2003. [Portuguese]

- ↑ C. D. Frailey et al, "A proposed Pleistocene/Holocene lake in the Amazon Basin and its significance to Amazonian geology and biogeography." Acta Amazonica, vol. 18, p. 119-143, 1988.

- ↑ "The Takutu Graben," The Guyana Chronicle Online, June 2, 2012

- ↑ Emilio Alberto Amaral Soares, "Depósitos pleistocenos da região de confluência dos rios Negro e Solimões, Amazonas," Doctoral thesis, University of São Paulo, Institute of Geosciences, 2007. [Portuguese]

- ↑ Hans ter Steege, Gerold Zondervan, "A Preliminary Analysis of Large-Scale Forest Inventory Data of the Guiana Shield," unpublished research.

- ↑ D. S. Hammond, "Socio-economic Aspects of Guiana Shield Forest Use," in Tropical Forests of the Guiana Shield Ancient Forests in a Modern World, Edited by D.S. Hammond, CABI Publishing, pp. 381–480.

- ↑ Ribeiro, Pedro A. Mentz et al. "Projeto Arqueológico de Salvamento no Territorio Federal de Roraima" (1986, 1987 1989) Cepa (Santa Cruz do Sul) 13 (16): 5–48; 14 (17): 1–81; 16 (19): 5-48-

- ↑ N. J. Reis et al, "Pedra Pintada, RR – Ícone do Lago Parime." In M. Winge, ed. Sítios Geológicos e Paleontológicos do Brasil, Brasília: CPRM, 2009; vol. 2, p 515. [Portuguese]

- ↑ J. A. Fonseca, "A Misteriosa Pedra Pintada (Roraima)", RCP Brasil [Portuguese]

- ↑ "Significant gold deposits in Roraima Basin – study," Stabroek News, March 22, 2009