Earth:Mount Karadağ

| Karadağ | |

|---|---|

Snow-capped Karadağ viewed from a village | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,288 m (7,507 ft) See Geography section |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 37°23′58″N 33°08′47″E / 37.39944°N 33.14639°E |

| Geography | |

| Location | Karaman, Turkey |

| Region | Central Anatolia Region |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Caldera |

| Last eruption | Unknown |

Karadağ (literally: Black mountain) is an extinct volcano in Karaman Province, Turkey. The mountain, which used to be a heavily inhabited mountain in the Hittite and Byzantine periods, is now used mostly for telecommunication purposes, but historical remains are still preserved, which many historical structures are still present.

Geography

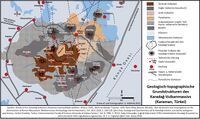

The Karadağ volcano rises in between the Çumra lowlands and the Hotamış marsh. The Mahalaç Peak is the highest point of the mountain, at 2,288 m (7,507 ft).[1] The caldera, also called the Uluçukur caldera, has a diameter of 2 km (1.2 mi) to 1.5 km (0.93 mi) with a depth of 150 m (490 ft). Surrounding the caldera can be found some lava domes. The volcanic complex covers an area of around 600 km2.[2]

Route to mountain

The mountain is accessible by car. Departing from Karaman, along the Karaman-Kılbasan road, making a left turn after passing Kılbasan will lead you to the mountain. Buildings of official institutions being located in the peak makes it easier to access the crater. The road from the older ages is thought to be near the current road.[1]

Flora and fauna

The region is home to around 250 wild horses.[3] On the mountain also can be found other animals such as feral sheep.[4]

The mountain is located near the Mediterranean Sea, which means it's climate is a mix of Mediterranean climate and continental climate. Due to this, the area is mostly covered by maquis. However, there are also some endemic plants, including the Astragalus vestitus.[5]

Geologic history

Volcanic activity in this volcano occurred in 4 phases (periods). The volcanic activity started in the end of Pliocene and continued until the end of Pleistocene. The oldest materials (around 2.3 million years old). The following volcanics have an age of around 1.95-2.05 million years old, which can be found in Kızıldağ, a cinder cone in the northeast of the main mountain. Later activity at the summit resulted in the creation of a caldera 1.1 million years ago. With these eruptions, andesites, tuffs, pumicites and formations of breccia were observed. In the north flank of the caldera, within the tuffs base surge sediments are visible. In the last period, the 4th period, near Madenşehri, younger andesite rocks were found. Older Neogene rocks were also found, consisting of conglomerates, limestones and sandstones in the area of the caldera.[6]

Caldera formation

Before the eruption which caused a caldera to form, the extrusion of slags, volcanic ash and debris was occurring. A lava flow covered the vent, which forced the pressure of the gas from the magma chamber to pile up and caused a large explosion, leaving a caldera behind. Pyroclastic flows were generated, the most effective being in the north flank. 2.5–4 m (8.2–13.1 ft) of pumice layers underground were found near Madenşehri as a result of the eruption.[2]

History

The slopes of the volcano have always been inhabited.[7] In fact, Çatalhöyük (ca 7500 BC), one of the earliest neolithic settlements in Anatolia, is located at the north-west of the volcano, and there are Hittite inscriptions on the hills at the south-east of the mountain.[8][9] The mountain was called Boratinon in late antiquity.[10] Ancient Derbe, which is one of the towns Paul the Apostle had visited, is situated on the east slopes of the mountain.[11] During the early ages of Christianity, the towns on the mountain were religious centers. There are ruins of early Byzantine settlements all around the mountain and the region is called Binbirkilise (English: Thousand and One Churches). Madenşehri ruins are situated to the north of the crater. However, after Christianity was well established in big cities, the settlements on the mountain lost their religious importance.

Gallery

See also

- List of volcanoes in Turkey

- Mountains of Turkey

- Kılbasan

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kurt, M. (2013). "Karadağ-Mahalaç Tepesi (Karaman) Üzerine Bir Araştırma" (in Turkish). Karamanoglu Mehmetbey University Journal of Social and Economic Research 2013 (1): 39–45. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/kmusekad/issue/10212/125486. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ermin, A. (2005) (in Turkish). Karadağ Volkanı'nın (Karaman) jeomorfolojik özellikleri. https://dspace.ankara.edu.tr/xmlui/handle/20.500.12575/28654. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ↑ Dik, B.; Ceylan, O.; Ceylan, C.; Tekindal, M. A.; Semassel, A.; Sonmez, G.; Derinbay Ekici, O. (2020). "Ectoparasites of feral horses [Equus ferus caballus (Linnaeus.,1758) on Karadag˘ Mountain, Karaman, Turkey"]. J Parasit Dis 44 (3): 590–596. doi:10.1007/s12639-020-01234-4. PMID 32801511.

- ↑ "Karaman Karadağ Yaban Hayatı - Karaman". Turkiye Kultur Portali. https://www.kulturportali.gov.tr/turkiye/karaman/TurizmAktiviteleri/karaman-karadag-yaban-hayati.

- ↑ Tugay, O.; Vural, M.; Ertuğrul, K.; Dural, H. (2014). "Astragalus vestitus'un Fabaceae yeniden keşfi: Kılbasan Geveni; Karadağ'ın Karaman / Türkiye lokal endemik bir türü" (in Turkish). Bağbahçe Bilim Dergisi 1 (2): 24–30. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/bagbahce/issue/53944/727540. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ↑ Koç, Ş. (2013). "Karadağ (Karaman) Volkanitlerinin Jeolojisi Ve "Base Surge" Oluşukları" (in Turkish). Journal of the Faculty of Engineering and Architecture of Gazi University 2 (2). https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/gazimmfd/issue/6639/88178. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ↑ "History of the city". Karaman Belediyesi. http://www.karaman.bel.tr/karaman/ing-tarih.aspx.

- ↑ Lloyd, Seton (1998) (in Turkish). Ancient Turkey(Trans: Ender Varinlioğlu). Ankara: Tubitak Yayınları. p. 269.

- ↑ "Karadağ Inscriptions". https://www.hittitemonuments.com/karadag/.

- ↑ Template:Cite DARE

- ↑ "Derbe". http://www.ctsp.co.il/LBS%20pages/LBS_derbe.htm.