Engineering:Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle

| Albemarle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle Mark I series 2 (P1475) of 511 Squadron c. 1943 | |

| Role | Transport, glider tug |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft |

| Built by | A W Hawksley Ltd |

| First flight | 20 March 1940 |

| Introduction | January 1943 |

| Retired | February 1946 |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force (RAF) Soviet Air Force |

| Produced | 1941–1944[1] |

| Number built | 602[2] |

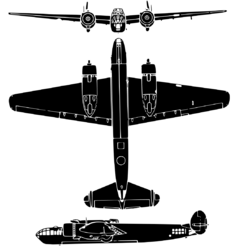

The Armstrong Whitworth A.W.41 Albemarle was a twin-engine transport aircraft developed by the British aircraft manufacturer Armstrong Whitworth and primarily produced by A.W. Hawksley Ltd, a subsidiary of the Gloster Aircraft Company. It was one of many aircraft which entered service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the Second World War.

The Albemarle had been originally designed as a medium bomber to fulfil Specification B.9/38 for an aircraft that could be built of wood and metal without using any light alloys; however, military planners decided to deemphasise the bomber role in favour of aerial reconnaissance and transport missions, leading to the aircraft being extensively redesigned mid-development. Performing its maiden flight on 20 March 1940, its entry to service was delayed by the redesign effort, thus the first RAF squadron to operate the Albemarle, No. 295 at RAF Harwell, did not receive the type in quantity until January 1943. As superior bombers, such as the Vickers Wellington, were already in use in quantity, all plans for using the Albemarle as a bomber were abandoned.

Instead, the Albemarle was used by RAF squadrons primarily for general and special transport duties, paratroop transport and glider towing, in addition to other secondary duties. Albemarle squadrons participated in Normandy landings and the assault on Arnhem during Operation Market Garden. While the Albemarle remained in service throughout the conflict, the final examples in RAF service were withdrawn less than a year after the war's end. During October 1942, the Soviet Air Force also opted to order 200 aircraft; of these, only a handful of Albemarles were delivered to the Soviets prior to the Soviet government deciding to suspend deliveries in May 1943, and later cancelling the order in favour of procuring the American Douglas C-47 Skytrain instead.

Development

Background

The origins of the Albemarle can be traced back to the mid-1930s and the issuing of Specification B.9/38 by the British Air Ministry.[3] This sought a twin-engine medium bomber of wood and metal construction, without the use of any light alloys, in order that the aircraft could be readily built by less experienced manufacturers from outside the aircraft industry. Furthermore, the envisioned aircraft had to be engineered in a manner that would allow it to be divided into relatively compact subsections, all of which had to fit on to a standard Queen Mary trailer to facilitate the adoption of a dispersed manufacturing strategy.[4] At the time, the Air Ministry was particularly concerned that, in the event of a major conflict arising, there would be restrictions on the supply of critical materials that could undermine mass production efforts.[4]

Several aircraft manufacturing firms, including Armstrong Whitworth, Bristol and de Havilland, were approached to produce designs to meet the specification. Bristol proposed two designs – a conventional undercarriage and an 80 ft (24 m) wingspan capable of 300 mph and a tricycle undercarriage design with 70 ft (21 m) span with a maximum speed of 320 mph (510 km/h). Both designs, known as the Type 155, used two Bristol Hercules engines. The rival Armstrong Whitworth AW.41 design used a tricycle undercarriage and was built up of sub-sections to ease manufacture by firms without aircraft construction experience.[4] The AW.41 was designed with Rolls-Royce Merlin engines in mind, but also with provisions for the use of Bristol Hercules as an alternative powerplant.[5]

In June 1938, mock-ups of both the AW.41 and Bristol 155 were examined, while revised specifications B.17/38 and B.18/38 were drawn up for the respective designs; de Havilland opted against submitting a design. The specification stipulated 250 mph (400 km/h) at 15,000 ft (4,600 m) economical cruise while carrying 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) of bombs. Bristol was already busy with other aircraft production and development and stopped work on the 155.[2][3] Changes in policy made the Air Staff reconsider the Albemarle as principally a reconnaissance aircraft capable of carrying out bombing. Among other effects, this meant more fuel to give a 4,000 mi (6,400 km) range. An upper dorsal turret and a (retractable) ventral turret for downward firing were added.[6]

Into production

In October 1938, 200 aircraft were ordered "off the drawing board" (i.e. without producing a prototype). The aircraft had a positive reputation and there were initially high hopes for its performance, however it never quite lived up to expectations.[7] Furthermore, according to aviation author Oliver Tapper, the brief was a relatively difficult one for any company to fulfil.[3] Initially, physical work centred around the construction of a pair of lead aircraft, which were to be test flown prior to the commencement of full-rate manufacture of the type. The first Albemarle, serial number P1360, was assembled at Hamble Aerodrome by Air Service Training; the aircraft performed its maiden flight on 20 March 1940.[8][3]

This first flight had actually been unintended, the test pilot having picked up too much speed during a ground taxi run, and had only taken off with the barest margin after traversing the entire runway.[9] Months later, P1360 was damaged after a forced landing during the test flight programme, but was promptly repaired. Early flights of the type by test pilots typically described it as being relatively average and being free of flaws.[9] A number of modifications were made to the design during this late stage of development, including the extensive redesign of the aircraft's structure by Lloyd at Coventry.[3] Further measures were made to improve the Albemarle's take-off performance, such as the adoption of a wider span 77 ft (23 m) wing, and the thickening of the rudder's trailing edge to correct a tendency to over-balance. Occurrences of the engines overheating were never fully resolved, the main change in this area being the raising of the maximum permissible operational temperature from 280C to 300C.[10]

The Albemarle's production run was principally undertaken by A.W. Hawksley Ltd of Gloucester, a subsidiary of the Gloster Aircraft Company, which was specifically formed to construct the Albemarle.[5] Originally, Gloster was to have undertaken this work itself at its Brockwood facility. Both Gloster and Armstrong Whitworth were member companies of the Hawker Siddeley group, one of the largest aircraft manufacturing interests in Britain.[5] Individual parts and sub-assemblies for the Albemarle were produced by in excess of 1,000 subcontractors.[5][11] Amongst the companies that were subcontracted were MG Motor, to produce the forward fuselage, Rover, which constructed the wing centre section, and Harris Lebus, which built the tailplane units.[5] Production of the Albemarle was terminated during December 1944, by which point 602 aircraft had been completed.[1]

Design

The Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle was a mid-wing cantilever monoplane with twin fins and rudders. The fuselage was built in three primary sections; the structure being composed of unstressed plywood over a steel tube frame, including four circular steel longerons; most elements were bolted together via gusset plates.[12][13] The structure was intentionally divided in order that it might readily permit individual sections to be removed and replaced in the event of battle damage being sustained. The centre section of the wing was a single piece that ran through the fuselage, being built around a steel tube girder; it formed the attachment points for the central and nose fuselage sections, as well as the engines, main undercarriage legs, and extension wings.[14] Aside from a portion of the leading edge that used light alloys, the majority of the wing was covered in plywood. The extension wings were almost entirely made of wood, save for the bracing of the two spars by steel tubing; the Frise-type ailerons and tailplane were also composed of wood.[14] The structure of the forward section used stainless steel tubing as to reduce interference with magnetic compasses.[15]

The Albemarle featured a Lockheed-designed hydraulically-operated, retractable tricycle undercarriage, the main wheels retracting back into the engine nacelles, and the nose wheel retracting backwards into the front fuselage, while the tail wheel was fixed in position, albeit semi-concealed by a "bumper" configuration. It was one of the particularly notable design features of the Albemarle, according to Tapper, it was the first British-built aircraft with a retractable nose-wheel to be built in quantity for the Royal Air Force .[5] Power was provided by a pair of Bristol Hercules XI air-cooled radial engines, each capable of 1,590 hp and driving a three-blade de Havilland Hydromatic propeller unit.[5] Fuel was typically stored in four tanks, two in the center fuselage and two within the wings centre section; in circumstances where extended range would be required, a maximum of additional auxiliary tanks could be installed within the aircraft's bomb bay. This sizable bomb bay was equipped with hydraulically-operated doors and spanned from just aft of the cockpit to roughly halfway between the wings and the tail.[14]

The two pilots sat side by side in the forward portion of the cockpit, while the radio operator was seated behind the pilots. The navigator's position was in the aircraft's nose, and thus was forward of the cockpit. The bomb aimer's sighting panel was incorporated into the crew hatch in the underside of the nose. In the rear fuselage, several glazed panels were present so that a "fire controller" could help coordinate the aircraft's defensive turrets against attackers. The dorsal turret was a Boulton-Paul design, which was electrically operated and originally armed with four Browning machine guns.[6] A fairing forward of the turret automatically retracted as the turret rotated to fire forwards.[16] The original bomber configuration of the Albemarle required a crew of six including two gunners; one in the four-gun dorsal turret and one in a manually operated twin-gun ventral turret but only the first 32 aircraft, the Mk I Series I, were produced in such a configuration.[17][18]

As a bomber, the Albemarle was commonly considered to be inferior to several other aircraft already in RAF service, such as the Vickers Wellington;[19] according to aviation author Ray Williams, the type was only used ever used as a bomber on two occasions.[17] Accordingly, later built aircraft were configured as transports, called either "General Transport" (GT) or "Special Transport" (ST). Amongst the modifications made was the elimination of the ventral turret, while the dorsal unit was downgraded to a manually-operated twin gun arrangement; the internal space was heavily altered by the elimination of bomb-aiming apparatus and the rear fuselage tank. Additions also included a quick-release hook, installed at the rearmost part of the fuselage for the towing of gliders.[14] When used as a paratroop transport, a maximum of ten fully armed troops could be carried; these paratroopers were provided with a dropping hatch in the rear fuselage along with a single large loading door in the starboard side of the fuselage.[20][14]

Operational history

Ambitions to use Albemarle in the bomber role were dropped almost immediately upon the type reaching service; this was due to it not representing an improvement over current medium bombers (such as the Vickers Wellington) and possessing inferior performance to the new generation four-engined heavy bombers that were also about to enter service with the RAF. However, the aircraft was considered to be suitable for general reconnaissance and transport duties, and thus was re-orientated towards such missions.[2]

The Soviet Air Force placed a contract for delivery of 200 Albemarles in October 1942. An RAF unit – No. 305 FTU, at RAF Errol near Dundee – was set up to train Soviet ferry crews.[21][22][23] During training, one aircraft was lost with no survivors. The first RAF squadron to operate the Albemarle was No. 295 at RAF Harwell in January 1943.[22] Other squadrons to be equipped with the Albemarle included No. 296, No. 297 and No. 570. The first operational flight was on 9 February 1943, in which a 296 Squadron Albemarle dropped leaflets over Lisieux in Normandy.[citation needed]

A Soviet-crewed Albemarle flew from Scotland to Vnukovo airfield, near Moscow, on 3 March 1943, and was followed soon afterwards by eleven more aircraft.[21] Two Albemarles were lost over the North Sea, one to German fighters and the other to unknown causes. Tests of the surviving Albemarles revealed their weaknesses as transports (notably the cramped interior) and numerous technical flaws; in May 1943, the Soviet government suspended deliveries and eventually cancelled them in favour of abundant American Douglas C-47 Skytrains. The Soviet camp at Errol Field continued until April 1944: apparently the Soviet government had hoped to secure de Havilland Mosquitos.[citation needed] Tapper speculated that a major reason for the Soviet's interest in the Albemarle had been its Bristol Hercules engines, which were reverse engineered and subsequently copied by Soviet industries.[22]

From mid-1943, RAF Albemarles took part in many British airborne operations, beginning with the invasion of Sicily.[24] The pinnacle of the aircraft's career was a series of operations for D-Day, on the night of 5/6 June 1944. 295 and 296 Squadrons sent aircraft to Normandy with the pathfinder force, and 295 Squadron claimed to be the first squadron to drop Allied airborne troops over Normandy. On 6 June 1944, four Albemarle squadrons and the operational training unit sent aircraft during Operation Tonga; 296 Squadron used 19 aircraft to tow Airspeed Horsas; 295 Squadron towed 21 Horsas, although it lost six in transit; 570 Squadron sent 22 aircraft with ten towing gliders; and 42 OTU used four aircraft. For Operation Mallard on 7 June 1944, the squadrons towed 220 Horsas and 30 Hamilcars to Normandy. On 17 September 1944, during Operation Market Garden at Arnhem, 54 Horsas and two Waco Hadrian gliders were towed to the Netherlands by 28 Albemarles of 296 and 297 squadrons; 45 aircraft were sent the following day towing gliders.[25] Of the 602 aircraft delivered, 17 were lost on operations and 81 lost in accidents.[citation needed]

The final RAF unit to operate the Albemarle was the Heavy Glider Conversion Unit, which replaced its examples with Handley Page Halifaxes during February 1946, at which point the type was formally retired from all operational units.[citation needed]

Variants

Over the course of its production life, a number of variants of the Albemarle were built:[26]

- ST Mk I – 99 aircraft

- GT Mk I – 69

- ST Mk II – 99

- Mk III – One prototype only.

- Mk IV – One prototype only.

- ST Mk V – 49

- ST Mk VI – 133

- GT Mk VI – 117

Most Marks were divided into "Series" to distinguish differences in equipment. The ST Mk I Series 1 (eight aircraft) had the four gun turret replaced with hand-operated twin-guns under a sliding hood. As a special transport, a loading door was fitted on the starboard side and the rear fuel tank was removed.[16] The 14 ST Mk I Series 2 aircraft were equipped with gear for towing gliders. The Mk II could carry ten paratroops and the Mk V was the same but for a fuel jettison system. All production Albemarles were powered by a pair of 1,590 hp (1,190 kW) Bristol Hercules XI radial engines. The Mk III and Mk IV Albemarles were development projects for testing different powerplants; the former used the Rolls-Royce Merlin III and the latter used the 1,600 hp (1,200 kW) Wright Double Cyclone.[27]

Operators

Soviet Union

Soviet Union

- Twelve aircraft were exported to the Soviet Union (two more lost in transit).

- Transport arm of 1st Air Division, later 10th Guards Air division (to 1944); naval air units until retirement in 1945.[citation needed]

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

- No. 161 Squadron RAF – Albemarle I from October 1942 to April 1943 at RAF Tempsford.

- No. 271 Squadron RAF operated one aircraft at Doncaster between October 1942 and April 1943.

- No. 295 Squadron RAF – Albemarle I from November 1943 to July 1944 at RAF Hurn and then RAF Harwell. Albemarle II from October 1943 to July 1944 at RAF Hurn and then RAF Harwell. Albemarle V from April 1944 to July 1944 at RAF Harwell.

- No. 296 Squadron RAF – Albemarle I from January 1943 to October 1944 at RAF Hurn, RAF Stoney Cross including operations in North Africa. Albemarle II from November 1943 to October 1944 at RAF Hurn and then RAF Brize Norton. Albemarle V from April 1944 to October 1944 at RAF Brize Norton. Albemarle VI from August 1944 to October 1944 at RAF Brize Norton.

- No. 297 Squadron RAF – Albemarle I from July 1943 to December 1944 at RAF Thruxton, RAF Stoney Cross and then RAF Brize Norton. Albemarle II from February 1943 to December 1944 at RAF Stoney Cross and then RAF Brize Norton. Albemarle V from April 1944 to December 1944 at RAF Brize Norton. Albemarle VI from July 1944 to December 1944 at RAF Brize Norton.

- No. 511 Squadron RAF – Albemarle I from November 1942 to March 1944 at RAF Lyneham.

- No. 570 Squadron RAF – Albemarle I from November 1943 to August 1944 at RAF Hurn and then RAF Harwell. Albemarle II from November 1943 to August 1944 at RAF Hurn and then RAF Harwell. Albemarle V from May 1944 to August 1944 at RAF Harwell.

- No. 1404 Flight RAF used three aircraft at RAF St Eval from September 1942 to March 1943

- No. 1406 Flight RAF used two aircraft at RAF Wick from September to October 1942.

- No. 13 Operational Training Unit RAF at RAF Finmere (two aircraft between October 1942 and April 1943)

- No. 42 Operational Training Unit RAF at RAF Ashbourne from September 1943 to February 1945.

- Heavy Glider Conversion Unit at RAF Brize Norton and RAF North Luffenham from January to April 1943 and August 1944 to October 1944 when it became No. 21 Heavy Glider Conversion Unit.

- No. 21 Heavy Glider Conversion Unit at RAF Brize Norton from 1944, moved to RAF Elsham Wolds in December 1945 and withdrew the last operational Albemarles in February 1946.

- No. 22 Heavy Glider Conversion Unit at RAF Keevil and RAF Blakehill from October 1944 to November 1945.

- No. 23 Heavy Glider Conversion Unit at RAF Peplow from October to December 1944.

- No. 3 Glider Training School operated eight Albemarles at RAF Exeter between January and August 1945.

- No. 301 Ferry Training Unit operated four Albemarles at RAF Lyneham from November 1942 to April 1943.

- No. 305 Ferry Training Unit bases at RAF Errol from January 1943 to train Soviet Air Force crews, disbanded in April 1944.

- Torpedo Development Unit at Gosport used one aircraft between April and September 1942

- Telecommunications Flying Unit at RAF Defford used one aircraft during May 1943,

- Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment at RAF Ringway and RAF Sherburn-in-Elmet between May 1942 and October 1944.

- Coastal Command Development Unit used two aircraft at RAF Tain between September and December 1942.

- Central Gunnery School at RAF Sutton Bridge used one aircraft between September and November 1942.

- Bomber Development Unit used three aircraft at RAF Gransden Lodge between August and November 1942.

- Operation Refresher Training Unit at RAF Hampstead Norris from May 1944 to February 1945

Aircraft were also operated for tests and trials by aircraft companies, the Royal Aircraft Establishment, and Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment. One was operated by De Havilland Propellers for research into reversing propellers.[citation needed]

Specifications (ST Mk I)

Data from The Unloved Albemarle,[28] Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft since 1913[29]

General characteristics

- Crew:

- Four (two pilots, navigator and radio operator) in Transport configuration

- Six (two pilots, navigator/bomb-aimer, radio operator and two gunners) in Bomber configuration

- Capacity: ten troops

- Length: 59 ft 11 in (18.26 m)

- Wingspan: 77 ft 0 in (23.47 m)

- Height: 15 ft 7 in (4.75 m)

- Wing area: 803.5 sq ft (74.65 m2)

- Empty weight: 25,347 lb (11,497 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 36,500 lb (16,556 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 769 imp gal (924 US gal; 3,500 L) normal, 1,399 imp gal (1,680 US gal; 6,360 L) with auxiliary tanks

- Powerplant: 2 × Bristol Hercules XI 14-cylinder air-cooled radial engines, 1,590 hp (1,190 kW) each

- Propellers: 3-bladed de Havilland Hydromatic

Performance

- Maximum speed: 265 mph (426 km/h, 230 kn) at 10,500 ft (3,200 m)

- Cruise speed: 170 mph (270 km/h, 150 kn)

- Stall speed: 70 mph (110 km/h, 61 kn) (flaps and undercarriage down)[30]

- Range: 1,300 mi (2,100 km, 1,100 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 18,000 ft (5,500 m)

- Rate of climb: 980 ft/min (5.0 m/s)

Armament

- Guns:

- Four × .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns in dorsal turret.

- Two × .303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns in ventral turret (first prototype only)

- Bombs: Internal bomb bay for 4,500 lb (2,000 kg) of bombs

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- CANT Z.1007

- Heinkel He 111

- Ilyushin Il-4

- Nakajima Ki-49

- Martin B-26 Marauder

- Mitsubishi G4M

- Savoia-Marchetti SM.79

- Savoia-Marchetti SM.81

Related lists

- List of aircraft of World War II

- List of aircraft of the RAF

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Tapper 1988, pp. 285.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Buttler 2004, p. 75.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Tapper 1988, p. 276.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Tapper 1988, pp. 276–277.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Tapper 1988, p. 277.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Tapper 1988, pp. 278–279.

- ↑ Tapper, Oliver (1973) (in en). Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft Since 1913. Putnam. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-370-10004-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=x3NTAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Mason 1994, pp. 335–337.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Tapper 1988, pp. 279–280.

- ↑ Tapper 1988, pp. 280–281.

- ↑ "British Aircraft of WWII." jaapteeuwen.com. Retrieved: 15 March 2007.

- ↑ Flight 27 January 1944, p. 89.

- ↑ Tapper 1988, pp. 277–278.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Tapper 1988, p. 278.

- ↑ Flight 27 January 1944, p. 90.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Flight 27 January 1944, p. 88.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Williams 1989, p. 37.

- ↑ Tapper 1988, p. 279.

- ↑ Williams 1989, p. 36.

- ↑ Bridgman, Leonard. Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. New York: Crescent Books, 1988. ISBN:0-517-67964-7.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Williams 1989, p. 41.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Tapper 1988, p. 283.

- ↑ Mark Felton video on Soviet use of Albemarles

- ↑ Tapper 1988, pp. 283–284.

- ↑ Tapper 1988, pp. 284–285.

- ↑ Tapper 1988, pp. 281, 286.

- ↑ Tapper 1988, p. 281.

- ↑ Williams 1989, p. 40.

- ↑ Tapper 1988, p. 286.

- ↑ "Albemarle", Air Transport Auxiliary Ferry Pilots Notes.

Bibliography

- Air Transport Auxiliary Ferry Pilots Notes. Elvington, Yorkshire, UK: Yorkshire Air Museum, Reproduction ed. 1996. ISBN:0-9512379-8-5.

- Bowyer, Michael J.F. Aircraft for the Royal Air Force: The "Griffon" Spitfire, The Albemarle Bomber and the Shetland Flying-Boat. London: Faber & Faber, 1980. ISBN:0-571-11515-2.

- Buttler, Tony. British Secret Projects: Fighters and Bombers 1935–1950. Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing, 2004. ISBN:1-85780-179-2.

- Mason, Francis K. The British Bomber since 1914. London: Putnam Aeronautical Books. 1994. ISBN:0-85177-861-5.

- Morgan, Eric B. "Albemarle". Twentyfirst Profile, Volume 1, No. 11. New Milton, Hants, UK: 21st Profile Ltd. ISSN 0961-8120.

- Tapper, Oliver. Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft since 1913. London: Putnam, 1988. ISBN:0-85177-826-7.

- Williams, Ray. "The Unloved Albemarle". Air Enthusiast, Thirty-nine, May–August 1989, pp. 29–42. ISSN 0143-5450.

- "Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle", Flight. 27 January 1944. pp. 87–91.

- Neil, Tom. "The Silver Spitfire" 2013. Wing Cmdr Neil includes his impressions of the Albemarle and his hair raising attempts to fly one without any instruction or manual.

External links

|