Engineering:Baris (ship)

| |

| General characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Type: | Traditional sailing ship |

| Length: | 10 m (32 ft 10 in)–30 m (98 ft 5 in) |

| Sail plan: | Square rig, papyrus mast |

| Notes: | Rudder runs through the hull |

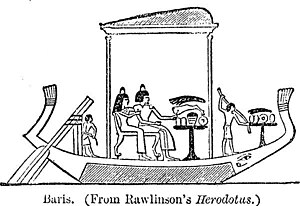

A baris (Ancient Egyptian: 𓃀𓅡𓄿𓏭𓂋𓏤𓊛, romanized: bꜣjr) is a type of Ancient Egyptian ship, whose unique method of construction[1] was described by Herodotus, writing in about 450 BC.[2] Archeologists and historians could find no corroboration of his description until the discovery of the remains of such a ship in the waters around Thonis-Heracleion in Aboukir Bay in 2003.

The ship, known as Ship 17, the first of 63 ships found in Thonis-Heraclion,[1] measures up to 28 metres (91 feet 10 inches) in length. They were constructed using an unusual technique to join thick wooden planks together, and had a distinctive steering mechanism with an axial rudder passing through the keel of the hull.[3][4] The underwater archaeological work was carried out by Franck Goddio and the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology, and the findings are being published in a book by Alexander Belov for the Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology.[3][4]

Herodotus' description

The cargo boats are made out of the wood of acacia, which is very similar in appearance to Cyrenean lotus and weeps gum. The way they make these boats is to cut planks of this acacia wood, each about two cubits long, and put them together like bricks. They use long, thick pins to fix these two-cubit planks together, and once the hull has been built this way, they next lay thwarts on top of it. Their boats have no ribbing, but instead they reinforce the fastenings on the inside of the boat with papyrus. They make a single-steering-oar, which is plugged in and through the keel. They use a mast of acacia wood and sails of papyrus. The boats are incapable of sailing upriver without strong following wind; instead, they are towed along from the bank.

Features

Herodotus reported that barides were built from acacia wood. Boards about 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long were sawn from the hard wood and the ship's hull was built from them by putting the boards together in a staggered manner. Cross braces stiffened the hull and the joints were sealed with papyrus. Herodotus emphasized that barides only had one rudder, as Greek ships were always equipped with two oars. There was an opening in the bottom of the ship through which the rudder was passed. They had a mast made of acacia wood with a sail made of papyrus.[5][6]

Ships could only travel up the Nile against the current when there was a strong northerly wind. Otherwise they would be towed against the current. Downriver, a kind of door made of tamarisk wood woven with reeds was used. It was attached to the bow of the ship with a rope and was lowered into the water so that the current pushed against the door and moved the ship. Attached to a second rope at the stern was a pierced stone weighing two talents (about 52 kilograms or 114 pounds 10 ounces), which was lowered to the bottom of the river. Due to the braking effect, the ship always kept its bow downstream. This type of ship is said to have been very common, and some ships are said to have had a carrying capacity of several thousand talents (1000 talents equals approximately 26 tonnes).[5][6]

Barides were flat-bottomed boats and could be either sailed or towed;[7] they were never equipped with oars.[8]

Etymology

Some etymologists and linguists[specify] hypothesize that the French word barge, whence the English word is derived, as well as the Spanish barco and the Italian barca, may be derived from the Vulgar Latin bārica. Bārica comes from the Latin bāris, which comes from the Ancient Greek βᾶρις (bâris), which is the Greek form of the Coptic ⲃⲁⲁⲣⲉ (baare).[9] It has traditionally been related to the Celtic *par, itself perhaps from Gaulish, from whence was derived the name of the Parisii (Gaul) (singular Parisius), the Celtic tribe which lends its name to the city of Paris;[10] this argument, however, is etymologically dubious; with several other hypotheses being recorded, including one from Alfred Holder linking it to the Parisii to the stem *pario-, meaning "cauldron."[11]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Belov, Alexander (2014). "A New Type of Construction Evidenced by Ship 17 of Thonis-Heracleion". The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (Moscow: Center for Egyptological Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences) 43 (2): 314–329. doi:10.1111/1095-9270.12060. https://www.um.es/cepoat/arqueologiasubacuatica/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/A_new_type_of_construction_evidenced_by.pdf. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- ↑ Solly, Meilan (21 March 2019). "Wreck of Unusual Ship Described by Herodotus Recovered From Nile Delta". https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/wreck-unusual-ship-described-herodotus-recovered-nile-delta-180971762/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Alberge, Dalya (17 March 2019). "Nile Shipwreck Discovery Proves Herodotus Right – After 2,469 Years". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/mar/17/nile-shipwreck-herodotus-archaeologists-thonis-heraclion. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ouellette, Jennifer (24 March 2019). "Shipwreck on Nile Vindicates Greek Historian's Account After 2500 Years". https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/03/shipwreck-on-nile-vindicates-greek-historians-account-after-2500-years/. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:0 - ↑ 6.0 6.1 Herodotus (1971) (in de). Historien: deutsche Gesamtausgabe. Kröners Taschenausgabe (4th ed.). Stuttgart: Kröner. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-3-520-22404-0.

- ↑ Smith, William (2013-03-28). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-06079-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139794602.

- ↑ Belov, Alexander (2020). "A Note on the Navigation Space of the Baris-Type Ships from Thonis-Heracleion". Sailing from Polis to Empire: Ships in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Hellenistic Period. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. ISBN 979-10-365-6304-1. https://books.openedition.org/obp/14399.

- ↑ "Barge". https://www.etymonline.com/word/barge#etymonline_v_5244.

- ↑ "Paris". https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=Paris.

- ↑ Delamarre, Xavier (2003) (in fr). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental. Collection des Hespérides (2nd ed.). Paris: Éditions Errance. pp. 247. ISBN 978-2-87772-369-5.

Further reading

- Belov, Alexander (2018). Ship 17: A Baris from Thonis-Heracleion. Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology. ISBN 9781905905362.

- Belov, Alexander (March 2014). "New Evidence for the Steering System of the Egyptian Baris (Herodotus 2.96)". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 43 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1111/1095-9270.12030.

- Herodotus. The History of Herodotus. http://classics.mit.edu/Herodotus/history.mb.txt.

- Pomey, Patrice (2015). "La batellerie nilotique gréco-romaine d’après la mosaïque de Palestrina" (in fr). La batellerie égyptienne. Archéologie, histoire, ethnographie. (Alexandria: Centre d’Études Alexandrines) (34): 151-172. https://www.academia.edu/19654580/La_batellerie_nilotique_gréco-romaine_daprès_la_mosaïque_de_Palestrina_in_P._Pomey_ed._La_batellerie_égyptienne._Archéologie_histoire_ethnographie._Etudes_Alexandrines_34_Alexandrie_2015_p._151-172.

|