Engineering:Board game

A board game is a type of tabletop game[2][3] that involves small objects (Template:Boardgloss) that are placed and moved in particular ways on a specially designed patterned game board,[4][5][6][7][8][9][10] potentially including other components, e.g. dice.[6] The earliest known uses of the term "board game" are between the 1840s and 1850s.[7][4][9]

While game boards are a necessary and sufficient condition of this genre, card games that do not use a standard deck of cards, as well as games that use neither cards nor a game board, are often colloquially included, with some referring to this genre generally as "table and board games" or simply "tabletop games".[2][3]

Eras

Ancient era

Board games have been played, traveled, and evolved in most cultures and societies throughout history[11] Board games have been discovered in a number of archaeological sites. The oldest discovered gaming pieces were discovered in southwest Turkey, a set of elaborate sculptured stones in sets of four designed for a chess-like game, which were created during the Bronze Age around 5,000 years ago.[12][13] Numerous archaeological finds of game boards exist that date from as early as the Neolithic period including, as of 2024, a total of 14 Neolithic sites reporting 51 game boards, ranging from mid-7th millennium BC to early 8th millennium BC.[14][15][16][17]

Oldest game

The Royal Game of Ur, estimated to have originated from around 4,600 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia, an example of which was found in the royal tombs of ancient Mesopotamia (c. 2600 BC – c. 2400 BC),[18][19][20] is considered the oldest playable boardgame in the world, with well-defined game rules discovered written on a cuneiform tablet by a Babylonian astronomer in c. 177 BC – c. 176 BC.[21][15]

Another game similar to the Royal Game of Ur was discovered in 1977 by the Italian Archaeological Mission in grave no. 731, a pseudo-catacomb grave at Shahr-i Sokhta, a UNESCO World Heritage archaeological site in Iran. This board game set, comprising 27 pieces and 4 different dice, dates to 2600–2400 BCE. For the first time, the entire set has been scientifically analyzed and reconstructed by researchers,[22] and it is considered the oldest complete and playable board game ever discovered.[23]

Currently, Senet is argued to be the oldest known board game in the world, with possible game board fragments (c. 3100 BC)[24] and undisputed pictorial representations (c. 2686;BC – c. 2613 BC)[25] having been found in Predynastic and First Dynasty burials dating as far back as 3500 BC.[26] However, while Senet was played for thousands of years, it fell out of fashion sometime after 400 A.D. during the Roman period;[25] the rules were never written down, therefore they are not decisively known.[27] Similarly, Mehen is one of the oldest games dated with reasonable confidence, i.e., c. 3000 BC – c. 2300 BC,[28][21] with some estimating it dates back to c. 3500 BC.[29] The rules, scoring system, and game pieces, however, are unknown or speculative.[29][21]

The title of the oldest known board game has been difficult to establish.[29] An example of this is mancala, which includes a broad family of board games with a core design of two rows of small circular divots or bowls carved into a surface, which has had numerous estimations of its generic age due to the many variants that have been discovered in different locations across Africa, the Middle East, and southern Asia.[29] These are dated across many different historical periods, from archaeological sites dating the game at c. 800 BC – c. 200 BC (Roman Settlements); c. 2500 BC – c. 1500 BC (Egypt); and even c. 7000 BC – c. 5000 BC (Jordan). The later based on divots carved out of limestone in a Neolithic dwelling from c. 5870 BC ± 240 BC,[16][29][30] although this later dating has been disputed.[31] Furthermore, when considering the Neolithic period game boards discoveries, caution has been given against considering these finds as representing earliest human game playing, as the absence of evidence of such games does not equate to evidence that no games were played during earlier periods.[32]

-

Men Playing Board Games, from The Sougandhika Parinaya Manuscript

-

Mehen game with game stones, from Abydos, Egypt, 3000 BC, Neues Museum

-

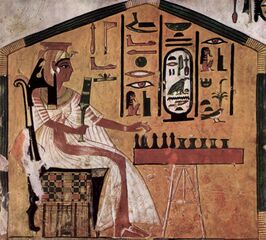

Painting in tomb of Egyptian queen Nefertari (1295–1255 BC) playing senet

Golden era

The 1880s–1920s was a board game epoch known as the "Golden Age", a term coined by American art historian Margaret Hofer[33] where the popularity of board games was boosted through mass production making them cheaper and more readily available.[34]: 11 The most popular of the board games sold during this period was Monopoly (1935), with 500 million games played as of 1999.[35]

Renaissance era

In the late 1990s, companies began producing more new games to serve a growing worldwide market.[36][37] The Settlers of Catan (1995) is often credited with popularising German-style board games outside of Europe and growing the hobbyist game market to a wider audience.[38] The early 21st century saw the emergence of a new "Golden Age" for board games called the "Board Game Renaissance".[36][39][40] This period of board games industry development, of which board games such as Carcassonne (2000) and Ticket to Ride (2004) were a major part, saw a shift away from the 20th-century domination by well-established standby Golden Era board games like Monopoly (1935) and Game of Life (1960).[41]

Regional history

Europe

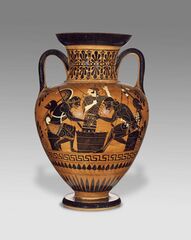

Board games have a long tradition in Europe. The oldest records of board gaming in Europe date back to Homer's Iliad (written in the 8th century BC), in which he mentions the Ancient Greek game of petteia.[42] This game of petteia would later evolve into the Roman game of ludus latrunculorum.[42]

- Germany

- Ireland

- Fidchell boards dating from the 10th century has been uncovered in Ireland,[44] with the game said to date back to at least 144 AD.[45]

- Scandinavia

- The ancient Norse game of hnefatafl was developed sometime before 400 AD.[46]

- United Kingdom

- In the United Kingdom, the association of dice and cards with gambling led to all dice games except backgammon being treated as "lotteries by dice" in the Gaming Acts of 1710 and 1845.[47] One of the most prolific publishers of board games of the late 18th and early 19th centuries was the English board game publisher John Wallis and his sons (John Wallis Jr. and Edward Wallis).[48] The global popularisation of board games, with special themes and branding, coincided with the formation of the global dominance of the British Empire.[49] Examples of british empire games included:

| Game title | Release date | Creator | Description | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Tour Through the British Colonies and Foreign Possessions | 1850 | John Betts | This board game was a race game that consisted of a board with 37 numbered pictures, each correlating to a British colony, arranged in four circular levels, numbered 1 (Heligoland, Germany) to 37 (London, England), three concentric ones and an inner fourth level of London ("Metropolis of the British Empire"). A teetotum was spun with a player's piece correspondingly moving ahead through the spaces of the game board, upon which a corresponding description to the space the player lands was read out aloud from an accompanying rule booklet by the presiding player (a player abstaining from directly playing the game), except when directed in the book. The descriptions included commentary about the various colonies and occasional game board movement directions to the player. There winner would be the player to reach London first. | [50][51][52] |

| A Voyage of Discovery, or The Five Navigators |

1836 | William Spooner | A race game where five players ('sailors') follow distinctly colored tracks, on a board decorated with islands; seas; and ships, with each player restricted to the path of their own color. The player's followed the instructions printed in circles along the tracks, which contained sailor-themed dangers and advantages. | [53] |

-

Achilles and Ajax playing a board game overseen by Athena, Attic black-figure neck amphora, c. 510 BC

-

Box for Board Games, c. 15th century, Walters Art Museum

-

An early games table desk (Germany, 1735) featuring chess/draughts (right) and nine men's morris (left)

Americas

The board game patolli originated in Mesoamerica and was played by a wide range of pre-Columbian cultures such as the Toltecs and the Aztecs.

- United States

- Due to a number of factors, such as the decrease of industrial working hours and the implementation of a Saturday half-day holiday, United States shifted from agrarian to urban living in the nineteenth century, which provided greater leisure time and a rise in middle class income.[54][55] The American home, once an economic production focus, started to become one for entertainment, enlightenment, and education under maternal supervision, where children were encouraged to play board games that developed literacy skills and provided moral instruction.[55]The first board games published in the United States were Travellers' Tour Through the United States and its sister game Traveller's Tour Through Europe, published in 1822 by New York City bookseller F. & R. Lockwood.[56][57] Margaret Hofer described this period, from 1880s–1920s, as "The Golden Age" of board gaming in America.[34] Board game popularity was boosted, like that of many items, through mass production, which made them cheaper and more easily available. In the 19th century, the industry itself was still developing, albeit significantly more rapidly; however, the games manufactured in America were still primarily for children.[58] Beginning in the late 20th century, during the period known as board game renaissance, games started to evolve considerably, from a strategic play standpoint and also in terms of increased advertising and marketing.[58] In modern day United States, board game venues have recently grown in popularity. In 2016 alone, more than 5,000 board game cafés opened in the United States.[59]

-

Patolli game being watched by Macuilxochitl as depicted on page 048 of the Codex Magliabechiano

-

The Mansion of Happiness (1843)

Asia

- Mesopotamia

- A version of the 4,600-year-old board game of the Royal Game of Ur, was found in the ancient Mesopotamian royal tombs of Ur (c. 2600 BC – c. 2400 BC),[26] is the oldest discovered playable board game.[56][60][61] The game's rules of this version were written on a cuneiform tablet by a Babylonian astronomer in 177 BC, and involved two players racing their pieces from one end of a 20-square board to the other in a similar way to backgammon, with the central squares being used for fortune telling.[61][21][12] Backgammon also originated in ancient Mesopotamia about 5,000 years ago.[62]

-

The Royal Game of Ur, southern Iraq, about c. 2600 BC – c. 2400 BC

- China

- Though speculative, Go has been thought to have originated in China somewhere in the 10th and 4th century BC.[63][64] While no archeological or reliable documentary evidence exists of the exact origins of the game, according to legend, Liubo was invented in around 1728–1675 BC in China by Wu Cao, a minister of King Jie the last Xia dynasty king. China developed a number of chess variants, including xiangqi (Chinese chess), dou shou qi (Chinese animal chess), and luzhanqi (Chinese army chess), each with their own variants.[65] Games like mahjong, and Fighting the Landlords (Dou DiZhu) also originated in China.In modern-day China, board game cafes have become popular, with cities like Shanghai having more game cafés than Starbucks.[66]

-

Han dynasty glazed pottery tomb figurines playing liubo, with six sticks laid out to the side of the game board

- India

- Ashtapada, chess, pachisi and chaupar originated in India. In modern day India, a community game called Carrom is popular.[67]

- In Thailand, makruk (Thai: หมากรุก), or Thai chess, is a strategy board game that is descended from the 6th-century Indian game of chaturanga or a close relative thereof, and is therefore related to chess. It is part of the family of chess variants.

- In Cambodia, where basically the same game is played, it is known as ouk (Khmer: អុក) or ouk chatrang (Khmer: អុកចត្រង្គ)

- Iran

- The Shahr-i Sokhta board game set, comprising 27 pieces and 4 different dice, dates to 2600–2400 BCE. The entire set has been scientifically analyzed and reconstructed by researchers, and it is considered the oldest complete and playable board game ever discovered.[23] Jiroft civilization game boards[68] in Iran, is one of several important historical sites, artifacts, and documents shed light on early board games.

-

The complete set of the Shahr-i Sokhta board game, Iran, with 27 pieces and 4 dice in its current condition, about c. 2600 BC – c. 2400 BC National Museum of Iran

-

The first-ever scholarly reconstruction of the Shahr-i Sokhta board game

-

Game board made of chlorite stone relief in the form of Scorpion man, characteristic of the gaming tradition in West Asia from the 3rd to 1st millennium B.C.

- South Korea

- A board game of flicking stones (Alkkagi) became popular among people in South Korea after various Korean variety shows demonstrated its gameplay on television.[69]

- Oman

- A stone slab carved with a grid and cup holes to hold game pieces constituting a large 4,000-year-old stone board game was located in a prehistoric settlement dated back to the Umm an-Nar period (c. 2600 BC to c. 2000 BC) near the village of Ayn Bani Saidahat in the Qumayrah Valley, Oman.[61]

Africa

In Africa and the Middle East, mancala is a popular board game archetype with many regional variations.

- Egypt

- The first complete set of this game was discovered from a Theban tomb that dates to the 13th dynasty.[70] Hounds and jackals, another ancient Egyptian board game, appeared around 2000 BC.[71][72] This game, originating c. 2600 BC – c. 2400 BC was also popular in Mesopotamia and the Caucasus.[73] Senet, originating from c. 2600 BC – c. 2400 BC, was found in Predynastic c. 3500 BC and First Dynasty c. 3100 BC burials of Egypt,[24] and pictured in fresco wall paintings and papyrus in Egyptian tombs, including the tombs of Merknera (c. 3300 BC–c. 2700 BC BC)[74][75] and Nikauhor and Sekhemhathor (c. 2465 BC–c. 2389 BC).[76] An ancient games from the African region included the predynastic Egyptian board game of mehen.[77][26]

-

Hounds and jackals (Egypt, 13th Dynasty)

-

Mancala board and clay playing pieces

-

Senet set inscribed with the Horus name of Amenhotep III (r. 1391–1353 BC)

Luck, strategy, and diplomacy

Some games, such as chess, depend completely on player skill, while many children's games such as Candy Land (1949) and snakes and ladders require no decisions by the players and are decided purely by luck.[78]

Many games require some level of both skill and luck. A player may be hampered by bad luck in backgammon, Monopoly, or Risk; but over many games, a skilled player will win more often.[79] The elements of luck can also make for more excitement at times, and allow for more diverse and multifaceted strategies, as concepts such as expected value and risk management must be considered.[80]

Luck may be introduced into a game by several methods. The use of dice of various sorts goes back to one of the earliest board games, the Royal Game of Ur. These can decide everything from how many steps a player moves their token, as in Monopoly, to how their forces fare in battle, as in Risk, or which resources a player gains, as in Catan (1995). Other games such as Sorry! (1934) use a deck of special cards that, when shuffled, create randomness. Scrabble (1948) creates a similar effect using randomly picked letters. Other games use spinners, timers of random length, or other sources of randomness. German-style board games are notable for often having fewer elements of luck than many North American board games.[81] Luck may be reduced in favor of skill by introducing symmetry between players. For example, in a dice game such as Ludo (c. 1896), by giving each player the choice of rolling the dice or using the previous player's roll.

Another important aspect of some games is diplomacy, that is, players, making deals with one another. Negotiation generally features only in games with three or more players, cooperative games being the exception. An important facet of Catan, for example, is convincing players to trade with you rather than with opponents. In Risk, two or more players may team up against others. Easy diplomacy involves convincing other players that someone else is winning and should therefore be teamed up against. Advanced diplomacy (e.g., in the aptly named game Diplomacy from 1954) consists of making elaborate plans together, with the possibility of betrayal.[82][83]

In perfect information games, such as chess, each player has complete information on the state of the game, but in other games, such as Tigris and Euphrates (1997) or Stratego (1946), some information is hidden from players.[84] This makes finding the best move more difficult and may involve estimating probabilities by the opponents.[85]

Software

Many board games are now available as video games. These are aptly termed digital board games, and their distinguishing characteristic compared to traditional board games is they can now be played online against a computer or other players. Some websites (such as boardgamearena.com, yucata.de, etc.)[86] allow play in real time and immediately show the opponents' moves, while others use email to notify the players after each move.[87] The Internet and cheaper home printing has also influenced board games via print-and-play games that may be purchased and printed.[88] Some games use external media such as audio cassettes or DVDs in accompaniment to the game.[89][90]

There are also virtual tabletop programs that allow online players to play a variety of existing and new board games through tools needed to manipulate the game board but do not necessarily enforce the game's rules, leaving this up to the players. There are generalized programs such as Vassal, Tabletop Simulator and Tabletopia that can be used to play any board or card game, while programs like Roll20 and Fantasy Grounds are more specialized for role-playing games.[91][92] Some of these virtual tabletops have worked with the license holders to allow for use of their game's assets within the program; for example, Fantasy Grounds has licenses for both Dungeons & Dragons and Pathfinder materials, while Tabletop Simulator allows game publishers to provide paid downloadable content for their games.[93][94] However, as these games offer the ability to add in the content through user modifications, there are also unlicensed uses of board game assets available through these programs.[95]

Market

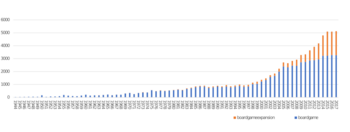

While the board gaming market is estimated to be smaller than that for video games, it has also experienced significant growth from the late 1990s.[39] A 2012 article in The Guardian described board games as "making a comeback".[96] Other expert sources suggest that board games never went away, and that board games have remained a popular leisure activity which has only grown over time.[97] Another from 2014 gave an estimate that put the growth of the board game market at "between 25% and 40% annually" since 2010, and described the current time as the "golden era for board games".[39] The rise in board game popularity has been attributed to quality improvement (more elegant mechanics, Template:Boardgloss, artwork, and graphics) as well as increased availability thanks to sales through the Internet.[39] Crowd-sourcing for board games is a large facet of the market, with $233 million raised on Kickstarter in 2020.[98]

A 1991 estimate for the global board game market was over $1.2 billion.[99] A 2001 estimate for the United States "board games and puzzle" market gave a value of under $400 million, and for United Kingdom, of about £50 million.[100] A 2009 estimate for the Korean market was put at 800 million won,[101] and another estimate for the American board game market for the same year was at about $800 million.[102] A 2011 estimate for the Chinese board game market was at over 10 billion yuan.[103] A 2013 estimate put the size of the German toy market at 2.7 billion euros (out of which the board games and puzzle market is worth about 375 million euros), and Polish markets at 2 billion and 280 million zlotys, respectively.[104] In 2009, Germany was considered to be the best market per capita, with the highest number of games sold per individual.[105]

Hobby board games

Some academics, such as Erica Price and Marco Arnaudo, have differentiated "hobby" board games and gamers from other board games and gamers.[106][107] A 2014 estimate placed the U.S. and Canada market for hobby board games (games produced for a "gamer" market) at only $75 million, with the total size of what it defined as the "hobby game market" ("the market for those games regardless of whether they're sold in the hobby channel or other channels") at over $700 million.[108] A similar 2015 estimate suggested a hobby game market value of almost $900 million.[109]

Research

A dedicated field of research into gaming exists, known as game studies or ludology.[110]

While there has been a fair amount of scientific research on the psychology of older board games (e.g., chess, Go, mancala), less has been done on contemporary board games such as Monopoly, Scrabble, and Risk,[111] and especially modern board games such as Catan, Agricola, and Pandemic. Much research has been carried out on chess, partly because many tournament players are publicly ranked in national and international lists, which makes it possible to compare their levels of expertise. The works of Adriaan de Groot, William Chase, Herbert A. Simon, and Fernand Gobet have established that knowledge, more than the ability to anticipate moves, plays an essential role in chess-playing ability.[112]

Linearly arranged board games have improved children's spatial numerical understanding. This is because the game is similar to a number line in that they promote a linear understanding of numbers rather than the innate logarithmic one.[113]

Research studies show that board games such as Snakes and Ladders result in children showing significant improvements in aspects of basic number skills such as counting, recognizing numbers, numerical estimation, and number comprehension. They also practice fine motor skills each time they grasp a game piece.[114] Playing board games has also been tied to improving children's executive functions[115] and help reduce risks of dementia for the elderly.[116][117] Related to this is a growing academic interest in the topic of game accessibility, culminating in the development of guidelines for assessing the accessibility of modern tabletop games[118] and the extent to which they are playable for people with disabilities.[119]

Additionally, board games can be therapeutic. Bruce Halpenny, a games inventor said when interviewed about his game, The Great Train Robbery:

With crime you deal with every basic human emotion and also have enough elements to combine action with melodrama. The player's imagination is fired as they plan to rob the train. Because of the gamble, they take in the early stage of the game there is a build-up of tension, which is immediately released once the train is robbed. Release of tension is therapeutic and useful in our society because most jobs are boring and repetitive.[120]

Playing games has been suggested as a viable addition to the traditional educational curriculum if the content is appropriate and the gameplay informs students on the curriculum content.[121][122]

Categories

Historical development

Harold Murray's A History of Board Games Other Than Chess (1952)[123] has been called the first attempt to develop a "scheme for the classification of board games", in which he separated board games into five categories: "race", "war", "hunt", "alignment" / "configuration", and "mancala" games.[124][58] Robert Bell's Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations (1960)[125] similarly espoused a classification of board games, this time divided into four categories, "race", "war", "positional", and "mancala" games.[58] In David Parlett's The Oxford History of Board Games (1999),[126] based on the work of Murray and Bell,[58] he described a "classical" categorization of board games which consisted of four primary categories: "race", "space", "chase", and "displace" games.[126][127]: 17

Modern board games have been classified in a variety of ways, a classification that can be based on the board game's mechanics, theme, age range, player number, and promotion. The diversity of board games means that some games belong to several categories.[128]: 13

Mechanics

A board game's mechanics usually involve an assessment of a player or player/s achievements while adhering to a series of pre-established Template:Boardgloss, i.e. Template:Boardgloss, such as capturing opponents' pieces, calculation of a final score, or achieving a predefined goal. Board games have a range of rule complexity but also a range of strategic depth, both of which determine the ease of mastering the game, i.e., hard-to-master games like chess possess a relatively simple rule set but have great strategic depth.[129] Examples of categories based on a modern categorization of a board game's mechanics include:[60]

| Board game categories | Description | Examples | Ref | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment | Alignment board games are a subcategory of space board games. In an alignment game, a player is required to position their tokens in an array of a prescribed length. Like space games, these games are often abstract games. | Renju; Gomoku; Connect6; Nine men's morris; Tic-tac-toe | [126][58][130] | ||||

| American-style | American-style board games are those from the North American region, usually having an emphasis on theme; randomness, usually through dice; numerous ways to win; and direct player conflict. These board games are also called Ameritrash board games; however, this term is not necessarily a negative label. | Betrayal at House on the Hill; Zombicide; Twilight Imperium; Arkham Horror; Talisman | [131] | ||||

| Auction | Auction board games are those that use bidding, a competitive assigning of value to different items, resources, privileges, or game scenarios, as a mechanism by which players attempt to obtain valuable in-game assets or establish a favorable turn order. These board games are also called bidding board games. | [132][133][131] | |||||

| Area control | Area control board games are those with some form of map or board defining a space that players compete to dominate, usually through adding their own pieces to regions or areas or removing their opponents' pieces. | Small World; Risk; Nanty Narking; Blood Rage; Spirit Island; Scythe; even arguably Scrabble | [134][131][130] | ||||

| Bluffing | Bluffing board games involve convincing opponent players on the accuracy of a claim, which includes tricking opponent players into believing something that is incorrect. All bluffing board games revolve around an element of hidden information. | Blood on the Clocktower; Coup; The Resistance; Sheriff of Nottingham; Skull; Shadows Over Camelot; Enigma Beyond Code; Bacchus' Banquet | [135][131][60][136] | ||||

| Campaign | Campaign board games are defined by players following a series of connected scenarios, where the actions and outcome of one scenario will usually affect the next. | Charterstone; Gloomhaven franchise games; Return to Dark Tower; The Ungame | [134][60][130] | ||||

| Chase | Chase board games often have an asymmetrical layout, where players start the game with different sets of pieces and objectives, usually rolling one or more dice to move a corresponding number of spaces along a looping track of spaces, or a path with a start and finish. When players land on certain spaces, it triggers specific actions or offers the player certain gameplay options. These board games are also known as roll-and-move games. | Classical: Hnefatafl; Snakes and ladders; Hyena chase Modern: Cluedo; Cranium; Monopoly; The Game of Life; Formula D | [126][134][130] | ||||

| Chess variant | Chess variant board games are displacement games that are variations upon the general chess concept. | Traditional: Shogi; Xiangqi; Janggi Modern: Chess960; Grand Chess; Hexagonal chess; Alice Chess | - | City building | City building board games involve building and managing a city via planning decisions, in a way that is efficient, powerful or lucrative. | 7 Wonders; The Capitals; Suburbia; Citadels; Catan; Everdell; Life in Reterra; Lisboa; On Mars; Puerto Rico; Underwater Cities (board game) (de) | [135][131][137] |

| Civilization building | Civilization building board games are those that involve developing and managing a society of people, often from scratch, requiring the contemplation of long-term strategy, good resource management, and sometimes even conflict with opponents. | 7 Wonders; Anno 1800; Civilization; Eclipse; Gaia; Shogun; Through The Ages; Terra Mystica franchise games; Twilight Imperium | [135][60][138] | ||||

| Collectible component | Collectible component board games involve collecting and trading certain game elements, usually cards and miniatures. These games are built around strategy and collection building, but also luck. These board games are also often called building board games. | Magic: The Gathering; Yu-Gi-Oh; Pokémon; KeyForge | [135][139] | ||||

| Configuration | Configuration board games are a sub-category of space games. However, as opposed to alignment games, the objective of players is to line up their pieces to complete per-determined array targets in a particular order. Like space games, these games are often abstract games. | Lines of Action; Hexade; Entropy | [126][58] | ||||

| Connection | A connection board game is often an abstract strategy game, in which players attempt to complete a specific type of connection with their pieces. This could involve forming a path between two or more endpoints, completing a closed loop, or a player connecting all of their pieces so they are adjacent to each other. | TwixT; Hex; Havannah | |||||

| Cooperative | Cooperative board games are those in which all the players work together to achieve a common goal rather than competing against each other. Either the players win the game by reaching a predetermined objective, or all players lose the game, often by not reaching the objective before a certain trigger event ends the game. These board games are also called non-competitive or co-op games. | [140][141][131][60][142][130] | |||||

| Count and capture | Count and capture board games are where players use tokens in rows of designated positions to capture their opponent's pieces. They are often also called sowing or mancala games. | Examples include: Mancala; Wari; Oware; The Glass Bead Game | |||||

| Cross and circle | Cross and circle board games are race games with a board consisting of a circle divided into four equal portions by a cross inscribed inside it like four spokes in a wheel. | Examples Cross and circle games that are also included: Yut; Ludo; Aggravation | |||||

| Deck-builder | In deck-builder board games, each player starts with their own identical deck of cards but alters it during play, with more powerful cards being added to the deck and less powerful ones being removed. | Aeon's End; Black Box; Clank! franchise games; Dominion (game); Dune: Imperium; Harry Potter: Hogwarts Battle (de); Hero Realms; Legendary: A Marvel Deck Building Game; Mystic Vale; Star Realms; Undaunted: Normandy | [134][135][131][60][130] | ||||

| Deck construction | Deck construction board games involve players using different decks of cards to play, constructed prior to the game from a large pool of options, according to specific rules. This type of board game is also called a trading card board game. | Android: Netrunner; Arkham Horror: The Card Game; Disney Lorcana; Keyforge; Magic: The Gathering; Marvel Champions; Pokémon; YU-Gi-OH! | [134][131][60] | ||||

| Deduction | Deduction board games involve requiring players to form conclusions based on what is occurring or has transpired based on available premises, such as provided clues either by the board game itself or by fellow players. These board games are also called Investigation games. Social deduction board games are a subcategory of deduction board games. | [134][135][60][143][144][131] | |||||

| Dexterity | Dexterity board games are those that require accurate movements of the body in response to real-time game situations. These games are a particular form of physical board game where fine motors skills are more important than physical attributes such as strength or endurance, including flicking, balancing, or even throwing objects around. Dexterity board games test motor skills, reflexes and coordination; and reward carefulness and punishing clumsiness. These board games are also known as action board games. | Flick 'em Up; Beasts of Balance; Dungeon Fighter; Flip Ships; Ghost Blitz (board game) (de); Jenga; Jungle Speed; Klask; Paku Paku (de); Pitch Car; Spot It!; Tumblin' Dice; What Next? | [134][135][131][60][145][146] | ||||

| Displacement | Displacement board games are those in which the main objective is the capture the opponents' pieces. These board games are also often called elimination or war board games. | Chess; Draughts; Alquerque; Fanorona; Yoté; Surakarta | [126] | ||||

| Drafting | Drafting board games involve a mechanism where players are presented with a set of options, usually cards, from which they must pick one, thus choosing the best options from a pool, leaving the remainder for the next player to choose from. They combine strategy, quick decision-making, and outguessing opponent players. The drafting mechanism can be a small part of a game, in order to select an ability for use during a round, or the entire decision space for a game. | 7 Wonders; Blood Rage; Bunny Kingdom (de); Citadels; Exploding Kittens; Sushi Go!; Ticket to Ride; It's a Wonderful World (board game) (fr) | [135][131][60][130] | ||||

| Dungeon-crawler | In dungeon-crawler board games, players take the roles of characters making their way through a location, often depicted by a map with a square grid or a page in a book, defeating enemies controlled by another player, a companion app, or the game system itself. | Descent; Gloomhaven franchise games; Betrayal at House on the Hill franchise games; HeroQuest; Mansions of Madness; Star Wars: Imperial Assault; Mice and Mystics | [135][131][130] | ||||

| Economic | Economic board games involve players managing resources and making smart decisions about how they spend or invest money. A player's strategy usually revolves around ensuring they have enough resources to achieve a strong financial position. Economic board games usually simulate a market in some way. These games are often also called Economic simulation games. The term economic board game is often used interchangeably with resource management board game. | [135][131][60][147] | |||||

| Educational | Educational board games are those designed to teach new ideas, concepts, topics or understanding while playing. The board game's learning is based on a particular theme. While educational games exist for different age groups, they are usually designed for children. | The Magic Labyrinth; Brain Quest; Cashflow; Evolution franchise games; Mariposas; Wingspan | [135][60][148] | ||||

| Engine-builder | Engine-builder board games are those where the course of the game involves building an engine, something that takes your starting resources or actions and turns them into more resources, which often eventually accumulate scored points. | Res Arcana (fr); Century; Everdell; Imagnarium; Race for the Galaxy; Splendor; Terraforming Mars; Wingspan | [134][135][131][130] | ||||

| Euro-style | Euro-style board games are those with a strategy focus, prioritising limited randomness over theme. These board games usually have competitive interactions between players through passive competition, rather than aggressive conflict, in contrast to the more thematic but chance-driven American-style board games. Euro-style board games are also called Eurogames or German-style board games due to the fact many of the early games of this style were developed in Germany. | Agricola; Catan; Carcassonne; Decatur; Carson City; Five tribes; Le Havre; Lords of Waterdeep; Montana; Paladins of the West Kingdom; Power Grid; Puerto Rico; Stone Age; Suburbia; Takenoko; Ticket to Ride | [134][135][131][60][130] | ||||

| Exploration | Exploration board games are those that have an unexplored map of tiles or cards, which the game encourages players to explore by flipping them and dealing with the consequences, either beneficial or detrimental. These board games are also often called Travel or 4x games. | Arkham Horror: The Card Game; Betrayal at House on the Hill franchise games; Eclipse; Gloomhaven franchise games; The Lost Expedition; Lost Ruins of Arnak; Robinson Crusoe; Twilight Imperium | [60][149] | ||||

| Fighting | Fighting board games are those that encourage players to engage game characters in close quarter battles and hand-to-hand combat. They differ from Wargames in that the combat in Wargames exists as one part of a large-scale military simulation, while in Fighting games the focus is on the particular combat scenarios. | Gloomhaven franchise games; Scythe; Spirit Island; War of the Ring | [150] | ||||

| Guessing | Guessing board games are those that involve a player, or players, guessing the answer to a question based on clues from another player. | Battleship; Mysterium; Pictionary | |||||

| Hidden movement | Hidden-movement games are defined as those that feature one or more players who move across the board, unseen to the other players. | Black Sonata; Captain Sonar; City of the Great Machine; Fury of Dracula; Letters from Whitechapel; Mind MGMT; Star Wars Rebellion | [151] | ||||

| Hidden role | Hidden-role board games involving a player, or players, with a hidden role within the group, where the rest of the players have to identify them, avoiding any influence or tricks used to deflect any suspicions that they have those roles. Sometimes called hidden traitor board games. | Mafia; The Resistance franchise games; Werewolf franchise games; Secret Hitler; Betrayal at House on the Hill franchise games | [135] | ||||

| Legacy | Legacy board games are a sub-category of campaign board games, as they also involve players following a series of connected scenarios, where the actions and outcome of one scenario will usually affect the next. However, in legacy board games, a player's choices and actions cause permanent, often physical, changes to the game and its components, such as applying stickers to the board or tearing up cards, thus providing a one-time experience. | Betrayal Legacy; Charterstone; Gloomhaven franchise games; Jurassic World: The Legacy of Isla Nublar; Pandemic Legacy; Ticket to Ride: Legands of the West | [134][135][131][130] | ||||

| Math | Math board games explicitly require players to use mathematical knowledge and concepts to achieve game objectives, thereby testing each player's number skills. These games combine mathematical skills, such as calculations, with regular game structures, such as sources of randomness. | Lost Cities; Sentient; The Shipwreck Arcana; Turning Machine; Prime Club; Qwixx (de); Math Fluxx | [135] | ||||

| Maze and labyrinth | A maze and labyrinth board game often requires players to navigate a series of complex pathways that are located on the game board. This type of board game tests a player's spatial awareness and problem-solving skills, often while adding in design elements from other types of board games. | Burgle Bros; RoboRally; Labyrinth; Magic Maze (fr); Sub Terra; Ricochet Robots; The Magic Labyrinth | [135][152] | ||||

| Memory | Memory board games concern memorizing certain facts, figures, and other information while testing a player's ability to recall sequences, locations, or specific items. | Codenames; Confusion; Cortex + Challenge; Enigma: Beyond code; Hanabi; The Magic Labyrinth; Memory; That's not a hat; 'The Resistance franchise games; Sideshow Swap; Simon; Wandering Towers; Whitehall Mystery; Witness | [135][60][153] | ||||

| Moral and spiritual development | Moral and spiritual development board games are those that prioritise player moral and spiritual development above any technical process of establishing a winner and loser. | Transformation Game;[154] Mansion of Happiness;[155][156][157][158] or Psyche's Key[159][160] | |||||

| Negotiation | Negotiation board games are where players must persuade fellow players to make deals and alliances or even offer bribes to get ahead in the game. The only exceptions to this are often euro games, which have stringent resource management rules. | Ca$h' n Guns; Cosmic Encounter; Diplomacy; Hegemony; The Resistance franchise games; Rising Sun; Sheriff of Nottingham; Twilight Imperium; Paydirt; Pax franchise games | [60][135][161] | ||||

| Number | Number board games are ones in which players are required to use or manipulate numbers to achieve their the games objectives. | That's Pretty Clever! (board game) (de); Arboretum; Take 5; The Shipwreck Arcana | [162] | ||||

| Paper-and-pencil | Paper-and-pencil board games are those that can be played solely with writing implements, usually without erasing. They may be played to pass the time, as icebreakers, or for brain training. | Dots and boxes; Hangman; MASH; Paper soccer; Spellbinder; Sprouts; Tic-tac-toe | [163] | ||||

| Party | Party board games are those that encourage social interaction. They are designed for larger groups of players with the aim of fostering social interaction amongst players, thus combining humour, creativity, and social interaction. | Classic: Charades; Pictionary Modern: Blood on the Clocktower; Codenames; Concept; Dixit; Decrypto; Just One; Mysterium; The Resistance franchise games; Secret Hitler; Snake Oil; Telestrations; Time's Up; Werewolf franchise games | [135][60][164] | ||||

| Physical | Physical board games are those involving physical challenges, and fall into two sub-categories:

|

Camp Granada; Flick 'em Up; Beasts of Balance; Dungeon Fighter; Flip Ships; Ghost Blitz (board game) (de); Jenga; Jungle Speed; Klask; Paku Paku (de); Pitch Car; Spot It!; Tumblin' Dice; What Next? | [145] | ||||

| Physical skill | Physical skill board games involve challenges involving gross motors skills, through assigning whole body movement tasks to players. | Camp Granada | |||||

| Position | Position board games are where the object is not to capture, but to win by leaving the opponent player unable to make a move. | Kōnane; Mū tōrere; L game | |||||

| Push-your-luck | Push-your-luck board games that invite you to take ever bigger risks to achieve increasingly valuable rewards against the risk of significant loss. These board games are also called press your luck board games. | Biblios; Formula D; The Captain is Dead: Dangerous Planet; King of Tokyo; The Quacks of Quedlinburg; Port Royale; Deep Sea Adventure; Welcome to the Dungeon (board game) (de) | [134][131][60][130] | ||||

| Puzzle | Puzzle board games are based on the solving of a puzzle or mystery and are commonly single-player games. | Classic: Peg solitaire; Sudoku Modern: Azul; Bärenpark; Blokus; Exit: The Game; Patchwork; Ubongo; Unlock! | [135][60][165] | ||||

| Race | Race board games are those in which each player has the goal of being the player to finish first, either by moving all their pieces to the final destination or completing an objective, e.g., the first player to collect five gems. This also includes games where the objective is to be the first to reach a checkpoint by navigation or steering around obstacles, usually by having greater speed or control than your opponents. The basic requirement is that race mechanics be an operative mechanism; however, racing is not required to be part of the board game's theme. | Classic: Agon; Pachisi; Backgammon; Chaupar; Chinese checkers; The bottle game; Dogs and jackals; Five-field kono; Grasshopper; Halma; Hyena chase; Kerala; Liubo; Ludo; Ludus duodecim scriptorum; Mehen; Nyout; Pachisi; Patolli; Royal Game of Ur; Salta; Saturankam; Senet; T'shu-p'u; Chowka bhara; Kilkenny Cats; Game of the goose; Zohn ahl Modern: Camel Up; Downforce and Rallyman: GT; Flamme Rouge (board game) (it); Formula D; Istanbul; Long Shot: The Dice Game; Montana; Heat: Pedal to the Metal; The Quest for El Dorado; Snow Tails; Thunder Road franchise games | [166][126][135][58][60][167][168] | ||||

| Role-playing | Role-playing board games are those where players assume a fictional character identity to participate in the game and its narrative. These games combine the character development and narrative of classic role-playing games with the mechanics of a board game. | Arcadia Quest; Dungeons & Dragons; Gloomhaven franchise games; Mage Knight; Mice and Mystics; Pathfinder; Shadowrun; Sword and Sorcery; Vampire: The Masquerade | [135][60][130] | ||||

| Real-time | Real-time board games are those with time limitations, usually playing against a timer, necessitating quick decision-making under pressure. In some real-time games, players take their turns simultaneously, creating a fast-paced, chaotic environment. | Captain Sonar; Galaxy Trucker; Pendulum; Space Alert; Speed chess; XCOM: The Board Game | [135][60][169] | ||||

| Resource management | The aim of resource management board games is to achieve objectives and gain an advantage through players acquiring, using, and managing a set of resources, which can be anything from physical materials, currency, and points to abstract concepts like time or influence. | Everdell; Imperial Settlers; Concordia; Scythe | [60][135][170][171][130] | ||||

| Roll-and-write | Roll-and-write board games are those where players roll dice and decide how to use the outcome, writing it into a personal scoring sheet. Each decision impacts on a player's options for the rest of the game, so even in games where everyone uses the same dice, slightly different choices at the start can lead to very different end results. Some games replace dice rolls with card exposure or the writing with miniature-based roll-and-build. | Bargain Basement Bathysphere; Corinth; Railroad Ink (de); Twilight Imperium; That's Pretty Clever! (board game) (de); Yahtzee | [134][131][130] | ||||

| Running-fight | Running-fight board games are those that combine the movement of race games with the goal of eliminating opponent player pieces like in chess or draughts. | ||||||

| Share-buying | Share-buying board games are those in which players buy stakes in each other's positions. These board games are typically longer economic-management games. | Acquire or Panamax | |||||

| Social deduction | Social deduction board games are those where one or more players have a secret that the rest of the players need to figure out. Often, players are secretly assigned roles known only to them and must achieve their own objectives, commonly either establishing the odd one out or hiding the fact that they are the odd one out. These board games generally involve deceit, bluffing, and accusations. | Blood on the Clocktower; Werewolf franchise games; The Resistance; Secret Hitler; Unfathomable | [134][135][131][60] | ||||

| Space | In space board games are often abstract games where the objective is for players to line up their pieces in order to complete predetermined array targets. Space board game fall into either two of the following sub-cateogires:

|

Connect6; Entropy; Gomoku; Hexade; Lines of Action; Nine men's morris; Noughts and crosses; Renju; Tic-tac-toe | [126][58] | ||||

| Storytelling | Story-telling board games are those with a focus on narrative and description that is directed or fully created by the players. This can be an overarching story lasting the whole game, or across a campaign of multiple sessions, read from pre-written passages, or a sequence of vignettes tasking players with inventing and describing something. Story-telling board games often test a player's creativity, improvisation, and sometimes acting skills. | Examples of story-telling games that are also board games include: Betrayal at House on the Hill; Dixit; Fog of Love; The King's Dilemma; Once Upon a Time; Tales of the Arabian Nights | [134][135][60] | ||||

| Stacking | Stacking board games involve players physically stacking and balancing game pieces. | Examples of stacking games that are also board games include: Boom Blast Stix; Bamboleo; Paku Paku (de); Animal Upon Animal; Junk Art; Jenga; Beasts of Balance; Lasca; Meeple Circus; Riff Raff; Rhino Hero; DVONN | [172] | ||||

| Territory building | In territory building board games, players establish or gain control over a specific area. These games often use area majority mechanics, also known as influence or enclosure mechanics, where areas are created as the game progresses. | The Castles of Burgundy; Faust; Terra Mystica franchise games; Go; Reversi; Risk; Scythe; Spirit Island; Terraforming Mars; War of the Ring | [173] | ||||

| Trivia | Trivia board games are those that test a player's ability to recall trivia facts. Many are based on a simple design that revolves around a deck of cards with questions. | Articulate!; Blockbuster: The Game; Fuana; Hipster; Half-Truth; Linkee!; Smart10 (fi); 'Timeline franchise games; Trivial Pursuit; Wits and Wagers | [135][131][60][174] | ||||

| Unequal forces | Unequal force board games are classified as any game whose core mechanics involve one player who is playing against all the other players right from the start or at least changes their allegiance, usually pledging it to the dark side. These board games are also known as hunt or one vs many board games. | Betrayal at House on the Hill; fox and geese; Fury of Dracula; Not Alone; Shadows Over Camelot; Tablut | [60] | ||||

| Word | Word board games involve the competitive use of language, testing each player's vocabulary, creative thinking skills, spelling or ability to quickly come up with words, phrases, or sentences. | Anagrams; Boggle; So Clover!; Codenames; Decrypto; Bananagrams; Just One; Paperback; Scrabble | [135][175] | ||||

| Worker-placement | Worker-placement board games are those where actions are taken by assigning worker tokens, from a player's allocated allotment, on designated game board spaces, which trigger specific actions, like collecting resources or completing tasks. Such board games are more commonly Euro-style board games, which concentrate on player interaction. Actions one player has taken often can not be taken by or come with a cost for other players. | Agricola; Charterstone; Caverna; Caylus; Dune: Imperium; Everdell; A Feast for Odin; Keyflower; Lords of Waterdeep; Ora et Labora; Stone Age; Tōkaidō; Village | [134][131][130] | ||||

| Wargame | Wargame board games are strategy-based board games with a war theme. Their mechanics are also closely tied to simulate battles, either fictional or historical, within differing settings, e.g. Napoleonic Wars, World War II, even Mars. Players pit armies against each other, represented by collections of miniatures or tokens on a map, with a grid or actual measured distances for movement. Players are required to eliminate the opponent's figures or achieve objectives to win, with combat usually dictated by dice rolls or card play. This type of game has three subcategories:

|

Examples include: Axis & Allies; Cry Havoc; Dune: Imperium; Inis, Kings of War; Memoir '44; Risk; Root; Star Wars: Armada; Scythe; Twilight Imperium; Undaunted: Normandy; Warhammer | [134][131][60][176][130] |

Theme

Parlett also distinguishes between abstract and thematic games, the latter having a specific genre or frame narrative, for examples regular chess versus Star Wars-themed chess.[124][60] The board games often have themes that emulate concepts in real-life situations or fictional scenario but can also have no evident theme.[177]

Such games have come under criticism, usually when trending thematic concepts, such as those based on popular television show licenses, have been used to supplement deficiencies in the game mechanics. When discussing this practice, Edwards wrote "A bad game, however, remains a bad game even if it has been themed to a favorite television show."[128]: 11 Parlett went so far as to describe these promotional and television spin-off games as being "of an essentially trivial, ephemeral, mind-numbing, and ultimately soul-destroying degree of worthlessness".[126]: 7

The prominent themes found in board games of the Golden Era included: travel, sports, courtship, racism, city life, war, education and capitalist enterprise".[33] Common modern thematic game categories include:

| Board game genres | Description | Examples | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adventure | An adventure-themed board game has themes of heroism, exploration, and puzzle-solving, often involving the game characters in quests. The storylines for these types of games often make them fantasy board games. | Gloomhaven franchise games; Nemesis; Clank! franchise games; Arkham Horror: The Card Game | [178] |

| Abstract strategy | An abstract strategy game is a game where player decisions, rather than random elements, determine the outcome. These games are combinatorial, meaning they provide perfect information rather than hidden or imperfect information, and rely on neither physical dexterity nor non-deterministic elements like shuffled cards or dice rolls during gameplay. Nearly all abstract strategy games are designed for two players or teams taking a finite number of alternating turns. Most games in this category are themeless or have minimal themes and typically lack narrative elements. | Examples of abstract strategy games that are also board games include:

|

[134][131][135][60][179] |

| Animal | Animal-themed games involve animals as a major component of the theme or gameplay, often requiring players to attend to their management or control. Players can even be required to take on the role of animals in the game. | Ark Nova; Great Western Trail; Root; Wingspan; Everdell | [180] |

| Arabian | Arabian-themed board games are generally fantasy or adventure games that are set in, or inspired by, locations on the Arabian Peninsula of the Middle East, the Persian Gulf, or North/East Africa, including themes and imagery such as deserts, palaces, camels, jewels, and oases etc. | Five Tribes; Targui; Camel Up; Wayfarers of the South Tigris; Through the Desert | [181] |

| Environmental | Environmental-themed games have themes and storylines regarding environmental conservation and management. | Pandemic Legacy; Ark Nova; Terraforming Mars; Spirit Island; Barrage; Cascadia | [182] |

| Civil War | Civil war-themed board games have storylines concerning a violent battle for government control between two more groups from the same country. The majority of Civil War games are also categorized as wargame board games. | Star Wars: Rebellion; Sekigahara: The Unification of Japan; Fire in the Lake; Pax franchise games; Caesar!: Seize Rome in 20 Minutes!; Resist! | [183] |

| Climbing | A climbing-themed board game is one thematically related to mountaineering or scaling a similarly steep surface, including a wall. | K2; Mountaineering; Climb!; Summit; Mountaineers | [184] |

| Fantasy | A fantasy-themed board game is one whose themes and scenarios exist in a fictional world, where magic and other supernatural forms are a primary element of the plot, theme or setting. | [185] | |

| Farming | A farming-themed game, usually a turn-based game revolving around building farms, growing crops, and raising livestock. | Agricola; Caverna; A Feast for Odin; Puerto Rico; Tzolk'in: The Mayan Calendar; Viticulture | [135][60][186] |

| Flight | Flight-themed board games have themes concerned with mechanical flight, including planes, helicopters, and gliders etc. | Sky Team; Star Wars: X-Wing Miniatures Game; Pan Am; The Manhattan Project; Star Wars: X-Wing Second Edition; Airlines Europe | [187] |

| Industry / manufacturing | Industry / manufacturing-themed games encourage players to build, manage or operate tools and machinery in order to manufacture raw materials into goods and products. Many industry / manufacturing-themed games are economic games. | Brass franchise games; Terraforming Mars; A Feast for Odin; Barrage; Food Chain Magnate | [188] |

| Historical simulation | A historical simulation board game is a game that attempts to create a realistic model of a historical event, battle, or encounter. The game uses rules and other ludic elements to construct meaning about the event, and players can use these elements to interpret the game in specific ways. Common periods of history which have provided themes for board games include:

|

General: Through The Ages or History of the World Before 4000 BC Prehistoric: Dominant Species; Stone Age; Paleo; Endless Winter: Paleoamericans; Evolution franchise games, or Oceans 3000 BC–476 Ancient: 7 Wonders Duel; 'Concordia franchise games; Lost Ruins of Arnak; Tzolk'in: The Mayan Calendar; Teotihuacan: City of Gods 476–1492 Medieval: The Castles of Burgundy; A Feast for Odin; Orléans; The Quacks of Quedlinburg; Paladins of the West Kingdom; El Grande 1380–1590 Renaissance: Azul; El Grande; Splendor; Keyflower; Lorenzo il Magnifico; Rajas of the Ganges 1500–1690 Pike and Shot: Sekigahara: The Unification of Japan; Merchants & Marauders; Here I Stand; Pax Renaissance; Wallenstein 1690–1789 Age of Reason: Brass franchise games; Rococo; Maria; Newton; Saint Petersburg; Imperial Struggle 1600–1800 American Indian Wars: A Few Acres of Snow; Wilderness War; Wendake; 1812: The Invasion of Canada (de); Navajo Wars; Wooden Ships and Iron Men 1775–1783 American Revolutionary War: Imperial Struggle; 1775: Rebellion; Washington's War; Liberty or Death: The American Insurrection; Wooden Ships and Iron Men; Sails of Glory (it) 1789–1815 Napoleonic: Commands & Colors: Napoleonics; Napoleon's Triumph; 1812: The Invasion of Canada (de), or Manoeuvre 1815–1914 Post-Napoleonic: Brass franchise games; Pax Pamir; Obsession; Trickerion: Legends of Illusion; Carnegie 1861–1865 American Civil War: Freedom: The Underground Railroad; Battle Cry; For the People; The Civil War 1861-1865; A House Divided 1850–1900 American Old West: Great Western Trail; Western Legends; Lewis & Clark: The Expedition; Boonlake; Colt Express 1914–1918 World War I: Memoir '44; Paths of Glory; The Grizzled; Wings of War: Famous Aces; Quartermaster General: 1914; Wings of War: First World War Series 1939–1945 World War II: Axis & Allies; Undaunted: Normandy; Memoir '44; Combat Commander: Europe; Air, Land, & Sea; Blitzkrieg!: World War Two in 20 Minutes; Black Orchestra Modern Warfare: Twilight Struggle; This War of Mine: The Board Game; Captain Sonar; Fire in the Lake; Labyrinth: The War on Terror, 2001–?; COIN franchise games 1945–1975 Vietnam Wars: Downtown: Air War Over Hanoi, 1965-1972; Fields of Fire franchise games; Fire in the Lake; Phantom Leader; Vietnam 1965-1975 1950–1953 Korean War: Fields of Fire franchise games; The Korean War: June 1950-May 1951; Korea: The Forgotten War; Flight Leader; The Speed of Heat | |

| Horror | A horror-themed game is one that contains themes and imagery depicting morbid topics that are associated with fear, terror, or dread, often also including supernatural elements. | [207][208][209][210] | |

| Mafia | Mafia-themed board games have themes, narratives or scenarios related to organized criminal groups. | The Godfather: Corleone's Empire; Ca$h 'n Guns; Scarface; Sons of Anarchy: Men of Mayhem; La Cosa Nostra | [211] |

| Medical | Medical-themed board games often can have elements of surgery, cures, recovery/recuperation/physical therapy, psychiatry, pharmaceutical prescription, and other medicine-related matters. | Pandemic franchise games or Unconscious Mind | [212] |

| Murder mystery | Murder mystery-themed board games are board games that often deduction or social deduction board games, where players investigate an unsolved murder, or murders, determining the criminal details or perpetrators. | Mansions of Madness; Blood on the Clocktower; Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective; Deception: Murder in Hong Kong | [135][213] |

| Musical | Musical board games are thematically linked to music, bands or the music industry. | Battle of the Bands; Cranium Pop 5; DropMix; Game that Song; Hitster (board game) (de); Humm Bug; Encore; Lacrimosa; Melody Infidelody; On Tour; Spontuneous; Schrille Stille ; Timeline: Music & Cinema | [214][215] |

| Mythology | Mythology-themed board games are those that incorporate a thematic narrative that defines how the game world or characters came into existence, especially those related or based on narratives of ancient civilizations. The storylines usually include supernatural elements, e.g. gods, goddesses and demigods, and are sometimes even set in a fabled or primordial time, which usually corresponds to a general corpus of folk stories (myths) that used to have some form of religious or sacred nature for the cultures focused on in the game. | Spirit Island; The Crew: Mission Deep Sea; Blood Rage; Oathsworn: Into the Deepwood; Mansions of Madness; Tzolk'in: The Mayan Calendar | [216] |

| Nautical | Nautical-themed board games involve sailors, ships or maritime navigation as a major component of the theme or gameplay, often requiring players to effectively control ships as an objective. | Concordia; The Crew: Mission Deep Sea; Underwater Cities; Sleeping Gods; Maracaibo; Le Havre | [217] |

| Other media | These are board games thematically link, derived or inspired from works or franchises in other media sources, including: | Comic books:

| |

| Pirate | A pirate-themed game has characters, themes, or storylines of nautical robbery or criminal violence, including treasure hunting, sea robbery, swords and cannons, swashbuckling, and ship racing etc. Pirate board games are usually thematically set between the 14th to 20th centuries. | Maracaibo; Skull King; Forgotten Waters; Merchants & Marauders; Dead Reckoning; Libertalia: Winds of Galecrest | [222] |

| Political | Political-themed board games encourage players to use their character's authority to manipulate societal activities and policy. | Twilight Imperium; Dune: Imperium; Twilight Struggle; Pax franchise games; Hegemony: Lead Your Class to Victory | [223] |

| Religion | Religious-themed games feature elements of their narrative, setting or characters that relate to current belief systems or religions of the world, either in their historical aspect and development through time, or their actual objects of faith, like sacred scriptures and articles of doctrine. | Here I Stand; Biblios; Orléans; Ora et Labora; Pax Renaissance; The Pillars of the Earth | [224] |

| Science fiction | Science fiction-themed board games often have themes relating to imagined possibilities in the sciences. Such games need not be futuristic, or they can be based on an alternative past. | Twilight Imperium; Dune: Imperium; Terraforming Mars; Star Wars: Rebellion; Gaia Project | [225] |

| Space exploration | Space exploration-themed board games have storylines relating to travel and adventure in outer space. Often players must seek and gather resources and territories as objectives of the game. These board games are also simply called Space games. | Alien: The Role Playing Game; Black Angel; The Crew (card game); Ganymede; High Frontier 4 All (board game) (es); Kepler-3042; Pulsar 2849; Race for the Galaxy; Space Base; Star Wars: Outer Rim; Starship Samurai; Terraforming Mar | [226][227] |

| Spies / secret agents | A spies / secret agents-themed board games often have themes or storylines relating to espionage. A common premise is that players must identify another player who has taken the role of spy or secret agent, in an attempt to reveal that player's allotted information. Since many Spies / Secret Agents-themed board games have an element of hidden information, they are therefore often also categorized as bluffing or deduction board games. | Pax franchise game; Pandemic Legacy; Decrypto; Battlestar Galactica: The Board Game; Codenames; Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective | [228] |

| Sports | Sports-themed board games have themes or storylines related to the physical activity of sports, including football and racing (whether car, boat, bicycle, or horse) etc. | Heat: Pedal to the Metal; Flamme Rouge (board game) (it); Long Shot: The Dice Game; Blood Bowl; Downforce; Ready Set Bet | [229] |

| Train | Train board games are those concerned with building and managing railway routes. They often combine elements from many other game types, requiring the use of strategy, planning, and economic skills to gain an advantage over other players. | Ticket to Ride franchise games; 18xx; Railways of the World; Colt Express; Age of Steam; TransAmerica | [230] |

| Travel | Travel-themed board games are travel-themed board games where the objective is to move to and from different geographic locations. Travel games usually employ a map as the main feature of the game board. | Lost Ruins of Arnak; Orléans; Lost Ruins of Arnak; The Voyages of Marco Polo; Darwin's Journey; Software:Tainted Grail: The Fall of Avalon; Eldritch Horror | [231] |

| Transportation | Transportation-themed board games are those that have gameplay involving the movement of goods or people from one place to another. | Brass franchise games; Keyflower; Age of Steam; Xia: Legends of a Drift System; Railways of the World | [232] |

| Zombie | Zombie-themed board games often contain themes and imagery concerning the animated dead, including common storylines themes of an apocalypse, horror, and fighting. These games are a thematic sub-category of Horror-themed board games. | Dead of Winter; Dawn of the Zeds; Zombicide; Zombie Kidz Evolution (de) | [233] |

Components

Board games can also be categorized by their components, including:[60]

| Board game audience | Description | Examples | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dice | Dice board games are those that use dice as their sole or principal component. | Example of dice games that are also board games, include: The Castles of Burgundy; King of Tokyo franchise games; Oathsworn: Into the Deepwood; Sky Team; Too Many Bones; Troyes; The Voyages of Marco Polo; Roll for the Galaxy | [135][60][234] |

| Book | Book board games are those where a book is a major operative component, can be separated into two types:

|

Gaslands; Four Against Darkness; Frostgrave; Spire's End; 'Ace of Aces franchise games | [235] |

| Card | Card board games are those where cards are the sole or central mechanism of the game. There are two types:

|

7 Wonders Duel; Anno 1800; Arkham Horror: The Card Game; Citadels; 'The Crew franchise games; Everdell; Splendor; Through the Ages: A Story of Civilization; Wingspan | [135][60][236] |

| Electronic | Electronic board games are those that have an electronic apparatus as the central component of the game, such as circuitry or sometimes simple computers. Electronic board games differ from both; electrified games, such as Operation which contain no circuitry; and those games requiring a website or app to be played. | Return to Dark Tower; Space Alert; Escape: The Curse of the Temple; Loopin' Louie; Escape Room: The Game; La Boca (board game) (it) | [237] |

| Game system | Game system board games are ones based around an item whose components are not a game of themselves, but are used to play games. | a piecepack; a decktet;[238][239][240] GEMJI tiles;[241][242] a chestego set;[243] a shibumi object;[244][245][246][247] Mü & Mores unique card deck; a traditional deck of cards; Unmatched's unique card deck; a Hanafuda; Unsettleds unique card deck; a rainbow deck[248] | |

| Miniatures | Miniatures board games are board games that use detailed miniature models to represent characters or units. Games of this type use miniatures as part of their game mechanics, combining tactics and strategy with collecting and artistry. Of all board game types, miniature games can be some of the most complex to produce, and time-consuming for players, who often are required to paint the models. | BattleTech; Blood Rage; Dead of Winter; Fury of Dracula; Gloomhaven franchise games; Mansions of Madness; Memoir '44; Nemesis; Rising Sun; 'Star Wars franchise miniature games; Santorini; War of the Ring; Warhammer 40,000 | [135][60][249] |

| Tile-based | A tile-based board game is one that uses small tiles as playing pieces or to create the board. These board games are also called "tile placement" or "tile-laying" board games. | [60] |

Age range

The recommended age range of board game's target player market impacts of the categorization of that board game:

| Board game audience | Description | Examples | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult / mature | Adult and mature board games are those designed exclusively for grown-up players. Compared to family or children's games, adult / mature board games usually involve mature subject matter, including violence, mystery or sexual humour etc. | Cards Against Humanity; Dead of Winter: The Long Night; Escape Tales: The Awakening; Kingdom Death: Monster; Tainted Grail franchise games; Monikers; Codenames: Deep Undercover | [135][58][250] |

| Children's | Children's board games are designed for kids and are usually straightforward enough for very young children to learn in a short period of time, having bright colors, and fun and engaging settings. | Mouse Trap; Animal Upon Animal; My First Stone Age; Dinosaur Escape and Candy Land; My Little Scythe; Perudo; PitchCar; Rhino Hero; Zombie Kidz Evolution (de) | [135][58][251] |

| Family | Family board games are those suitable for the entire family, including adults who play together with younger children. | Artriculate; Birds on a Wire; For Sale; Herd Mentality; Photosynthesis; Roll Through the Ages; Sushi Go; Ticket to Ride; or Wingspan | [58][252] |

Player number

| Board Game Audience | Examples | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Large multiplayer | Take It Easy; Swat | |

| Multiplayer | Risk; Monopoly; Four-player chess | |

| Two-player | En Garde; Dos de Mayo |

Promotion type

The following categories of board games are not board game types but rather paths board game creators take to promote their game:[60]

| Promotional Approach | Description | Examples | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collectable | A collectible board game is a special edition of a board game that has limited copies, such as anniversaries or deluxe versions. | [60] | |

| Expansion | An expansion of the base board game is a set of additional components and rules for expanding on an original base game. An "expansion" requires the base game to play. |

|

[261] |

| Fan expansion | Fan expansion board games are non-commercial enhancements made by people other than a base game's designers or publishers. These are also called "unofficial" board games. |

|

[268] |

| Print-and-play (de) | Print-and-play board games are those not published in a physical form but are those that require the players to download, print, and construct the game. Often, these games are downloaded electronically as a PDF file. | Air, Land, & Sea; Corinth; Evolution: Climate; Monikers; The Resistance; Rolling Realms; Root; Secret Hitler; Tiny Epic Galazies | [60][88][269] |

| Travel | Travel versions of board games that are more amenable for packing and carrying while traveling, having smaller game components to make them more compact, and simplified rules to make them quicker to play. | Compact versions of chess, or checkers | [135] |

Glossary

Although many board games have a jargon all their own, there is terminology that is recognized and widely shared by gamers and the gaming industry.

See also

- Board game awards

- BoardGameGeek – a website for board game enthusiasts

- Going Cardboard – a documentary movie

- History of games

- Interactive movie – DVD games

- List of board games

- List of game manufacturers

- Mind sport

References

- ↑ "You can choose cities for new Monopoly game". NBC News. 20 February 2008. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna23238096.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Woods, Stewart (16 August 2012). Eurogames: The Design, Culture and Play of Modern European Board Games. McFarland. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7864-9065-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=xgmjCHxSxvoC&q=history+of+board+games&pg=PP1. Alt URL

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Engelstein, Geoffrey (21 December 2020) (in en). Game Production: Prototyping and Producing Your Board Game. CRC Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-000-29098-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=OpEIEAAAQBAJ&dq=%22tabletop+games%22+%22game+board%22&pg=PP10. Alt URL

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Board game" (in en). https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/board%20game.

- ↑ "Board game" (in en). https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/board-game.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Board game" (in en). https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/board-game.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Board game" (in en). https://www.oed.com/dictionary/board-game_n?tab=factsheet&tl=true#1410500690.

- ↑ "Board game" (in en). https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/board-game.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Board Game" (in en). https://www.dictionary.com/browse/board%20game.

- ↑ "Board game" (in en). https://www.britannica.com/dictionary/board-game.

- ↑ Livingstone, Ian; Wallis, James (2019). Board games in 100 moves. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-241-36378-2. OCLC 1078419452.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Solly, Meilan. "The Best Board Games of the Ancient World" (in en). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/best-board-games-ancient-world-180974094.

- ↑ Lorenzi, Rossella (14 August 2013). "Oldest Gaming Tokens Found in Turkey" (in en). http://news.discovery.com/history/archaeology/oldest-gaming-tokens-found-130814.htm.

- ↑ Rollefson, Gary (December 2024). "What are the odds? Neolithic "game boards" from the Levant" (in en). Journal of Arid Environments 225 (105257). doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2024.105257. Bibcode: 2024JArEn.22505257R. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S014019632400137X. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Finkel, Irving L. (2007). "3. On the Rules for the Royal Game of Ur" (in en). Ancient Board Games in Perspective | Papers from the 1990 British Museum colloquium, with additional contributions. London: British Museum Press. p. 16. https://csclub.uwaterloo.ca/~pbarfuss/On_the_Rules_for_the_Royal_Game_of_Ur.pdf. Retrieved 17 April 2025. Alt URL

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Simpson, St John (2007). "1. Homo Ludens: The Earliest Board Games in the Near East". in I.L. Finkel (in en). Ancient Board Games in perspective: Papers from the 1990 British Museum colloquium, with additional contributions. London: British Museum Press. pp. 5–10. https://www.academia.edu/3584121. Retrieved 17 April 2025.

- ↑ Rollefson, Gary (December 2012). "La Prehistoire des jeux" (in fr). Histoire Antique & Médiévale (33): 18–21. https://www.faton.fr/dossiers-dhistoire/numero-33/art-jeu-jeu-l-art/prehistoire-jeux.32646.php#article_32646. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- ↑ "game-board: Museum number 120834" (in en). pp. 11–15. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1928-1009-378. Alt URL

- ↑ Finkel, Irving L. (2007). I.L. Finkel. ed (in en). Ancient board games in perspective | Papers from the 1990 British Museum colloquium, with additional contributions. London: British Museum Press. https://annas-archive.org/md5/189bf3233143e3aa74a521089bae39dc. Retrieved 17 April 2025.

- ↑ Depaulis, Thierry (1 October 2020). "Board Games Before Ur?" (in en). Board Game Studies Journal 14 (1): 127–144. doi:10.2478/bgs-2020-0007. ISSN 2183-3311. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350710812. Retrieved 17 April 2025. Alt URL

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 "Top 10 historical board games" (in en). 26 February 2021. https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/top-10-historical-board-games.

- ↑ Jelveh, Sam; Moradi, Hossein (4 December 2024). Analysis of the Shahr-i Sokhta Board Game and Suggested Rules Based on the Royal Game of Ur. doi:10.31235/osf.io/kctnj. https://osf.io/kctnj/download. Retrieved 26 July 2025.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Hsu, Jeremy (14 December 2024). "Games of old". New Scientist 264 (3521): 48–49. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(24)02191-2. ISSN 0262-4079. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0262407924021912.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Piccione, Peter A. (July–August 1980). "In Search of the Meaning of Senet". Archaeology: 55–58. http://www.piccionep.people.cofc.edu/piccione_senet.pdf. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Sebbane, Michael (2001). "Board Games from Canaan in the early and intermediate Bronze Ages and the origin of the Egyptian Senet game". Tel Aviv 28 (2): 213–230. doi:10.1179/tav.2001.2001.2.213.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "8 Oldest Board Games in the World" (in en). https://www.oldest.org/entertainment/board-games.

- ↑ Dove, Laurie L. (4 April 2012). "How Senet Works" (in en). https://entertainment.howstuffworks.com/leisure/brain-games/senet.htm#pt1.

- ↑ Crist, Walter (2016). Ancient Egyptians at Play: Board Games Across Borders. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 15–38. ISBN 978-1-4742-2117-7.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 "The Oldest Games in the World" (in en). 31 July 2023. https://www.goodgames.com.au/articles/the-oldest-board-games-in-the-world.

- ↑ "Mancala". https://www.savannahafricanartmuseum.org/2020-workshops/05-2#:~:text=There%20is%20archeological%20and%20historical,floor%20of%20a%20Neolithic%20dwelling.

- ↑ Depaulis, Thierry (1 October 2020). "Board Games Before Ur?" (in en). Board Game Studies Journal 14 (1): 127–144. doi:10.2478/bgs-2020-0007. ISSN 2183-3311.