Engineering:European Union submarine internet cables

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Submarine internet cables, also referred to as submarine communications cables or submarine fiber optic cables, connect different locations and data centres to reliably exchange digital information at a high speed.

They are significant providers of internet connection globally: 99% of international communications go through submarine fibre optic cables,[1] as well as US$10 trillion of financial transactions every day.[2] The European Union (EU), in particular, has a strong need for connection, since 87% of EU citizens were internet users in 2021.[3]

Network description

External network

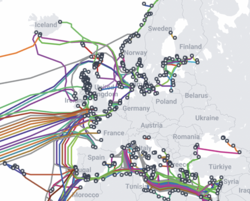

In May 2023, the EU has direct connections with:[4]

- North America: 9 undersea cables (Dunant, MAREA, Apollo, Grace Hopper, FLAG Atlantic-1, AC-1, AEC-1, AEC-2, EXA Express, EXA North and South). 1 is being installed (Amitié).

- South and East Asia: 8 undersea cables (PEACE, AAE-1, SeaMeWe-3, SeaMeWe-4, SeaMeWe-5, IMEWE, Europe India Gateway, FEA). 4 are being installed (SeaMeWe-6, Africa-1, 2Africa, IEX).

- MENA region: 27 undersea cables. All cables going to Asia are also connected to the MENA region. Other cables are TE North, MedNautilus, Hawk, ORVAL, Estepona-Tetouan, Atlas Offshore, Canalink, EllaLink, Med Cable Network, KELTRA-2, Didon, HANNIBAL system, Italy-Libya, Silphium, UGARIT, Turcyos-1, Turcyos-2, CADMOS, KAFOS. 3 are being installed (Blue, Medusa submarine cable system, CADMOS-2).

- West, Eastern and South Africa: 5 undersea cables (SAT-3, MainOne, ACE, Equiano, PEACE). 2 are being installed (2Africa, Africa-1).

- South America: 1 undersea cable (EllaLink).

- Oceania: 1 undersea cable (SeaMeWe-3).

The EU is also highly connected to the United Kingdom (UK), as 23 undersea cables connect the two.[4] In 2016, the EU lost a considerable number of connections because of Brexit, especially with North America. However, it does not represent a danger to EU connectivity, because there is a strong collaboration and the EU infrastructure remains able to do without the UK.[5]

Internal network

In May 2023, the EU has 39 undersea cables that connect Member States exclusively.[4] 3 are being installed (Digital E4, Eastern Light Sweden-Finland II, Ionian). These cables mostly connect Island States (such as Malta) or States around the Baltic Sea.

- Cables in Northern Europe (31): COBRAcable, GlobalConnect 2, Kattegat 2, Denmark-Sweden 16, Denmark-Sweden 17, Denmark-Sweden 18, Scandinavian Ring North, Scandinavian Ring South, Danica North, IP-Only Denmark-Sweden, Baltica, NordBalt, Latvia-Sweden 1, Sweden-Latvia, Baltic Sea Submarine cable, Eastern Light Sweden-Finland I, BCS North-Phase 1, Sweden-Finland 4, Sweden-Finland Link, Sweden-Estonia, C-Lion1, Finland-Estonia 2, Finland-Estonia 3, Finland-Estonia connection, Botnia, BCS East, BCS East-West Interlink, Denmark-Poland 2, Germany-Denmark 3, GlobalConnect-KPN, Fehmarn Bält.

- Cables in Southern Europe (8): Malta-Italy interconnector, Melita 1, Epic Malta-Sicily Cable System, Italy-Malta, GO-1 mediterranean cable system, Italy-Greece 1, OTEGlobe Kokkini-Bari, Italy-Croatia.

Status

International law

The law ruling submarine internet cables is UNCLOS. The creation of the internet and of the physical infrastructure that underlies it only happened in 1986, after UNCLOS was signed,[6] but the research had been progressing in the 1970s, pushing the industry to give an interest in this framework's elaboration. Laying cables is part of the "freedom of the seas" (article 87). The location of submarine cables was considered a core element of negotiations. It established delimited areas such as the EEZ.[7] It is therefore authorized everywhere except in territorial waters, where Coastal states edict their own rules. It is assumed that this freedom also applies to maintaining and repairing cables.[6] However, States that would like to lay a cable must do it in consideration to other infrastructure that might be already installed. In addition, if it is in another State's EEZ, it must take into consideration the exclusive rights the coastal State possesses in this zone (economic resources, etc.) (article 79).[7]

Submarine internet cables are privately owned, mostly by telecommunications companies.[8] However, tech companies have started investing in the cable business as well (such as Meta and Google). Most cables are owned and managed by consortiums of companies.[8] In UNCLOS, owners are liable for damages that could happen to the cables (article 114). These regulations only apply to nationals. They must also be able to compensate ships and fishermen in cases where they would have damaged their fishing gear or anchor to avoid hurting submarine cables (article 115).[6] Finally, States have the obligation of making damages to submarine internet cables a punishable offence (article 113), except if it is unavoidable with lives or ships at stake.[6] With the growing discussions following climate change and environmental issue, submarine cables' sustainable protection ought to be a priority. Human actions on oceans are difficult to assess.[7] There are already measures taken such as data collection of ocean temperatures, ocean water pressure and its salinity.[9] However, there is no clear mandatory rule within the UNCLOS to enforce those actions.[7]

The European Union

In the EU, the regulation of cyberspace and internet infrastructure was originally left to private companies themselves. Internet was thought of as a "free" place, which was reflected in the internet governance. The US were at its core.[10] This changed when large cyberattacks targeted European governments, Estonia in 2007 and Georgia in 2008, following disagreements with Russia. States – and the EU – started to get involved in regulating the internet. Indeed, with five of its Member States (France, Denmark, Italy, Portugal and Spain) as the core contributors to the continent connectiveness to the world, the EU comprehended its importance.[11] It is only recently that the interest to submarine internet cables came to be considered a strategic and geopolitical stake. The Russo-Ukrainian War, and especially the Nord Stream attack, massively boosted the interest given to internet and energy infrastructure.

Despite this turnover in attention, the EU has not been actively setting the protection of submarine cables as a top priority. Maritime security authorities give priority to other issues such as piracy, people smuggling, and environmental protection.[12] Fishery, which represents, in certain EU countries such as Spain, Italy and Greece, up to 62% of employment,[13] is closely linked to submarine cables protection. However, it has been often deemed an irrelevant issue to fishery organizations.[5]

Most generally, the task of cables' care falls in the jurisdiction of national governments. In its 2023 report, the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) describes the different regulatory regimes present in the EU:

- In France, a combination of the Secretariat-General for National Defence and Security, the Secrétariat général de la Mer and the French Navy deals with the protection of the cables. The two former take care of the supervision of measures taken. The latter collaborates with companies such as Orange Marine to proceed with various checks and actions to maintain the cables’ conditions.[14]

- In Portugal, the handling of submarine cables is divided among different entities with the Autoridade Nacional de Comunicações – ANACOM, as its main contributor. ANACOM facilitates the obtention of permits related to the maintenance and establishment of cables. It develops systems analysing the environment surrounding the cables as well as an alert system to warn ships entering subsea cable routes.[14] The unclearness of rules for ships to maintain a distance with cables has often been blamed for why legal advancement has been slow.[15]

- In many other countries such as Bulgaria and Sweden, private companies that own the cables are responsible for their security.[14]

Internet cables were not considered a European critical infrastructure in the 2008 European Programme for Critical Infrastructure Protection.[16] The 2013 update however underlines that new technologies have developed and that cyberspace should start being taken into account.[17] Today, submarine internet cables are considered a critical infrastructure by the European Union, as part of the category "information and communication systems".[18]

Threats

Submarine internet cables are subject to threats and damages of different kinds, to which the EU is more or less vulnerable. Three categories can be distinguished: natural causes, unintentional human causes and intentional human causes.

Natural threats

The first kind of damages to internet cables are natural hazards. Overall, they account for less than 10% of all submarine internet cables damages.[19] Natural hazards comprise:

- Shark/fish bites. There is no consensus as to why sharks bite undersea cables. Hypotheses are curiosity, or confusion with food due to the cables’ electric field (similar to electromagnetic fields sensed from their preys).[20] They remain a marginal threat: fish bite accounts for only 0.5% of cable faults over the period 1959–2006.[21] They are mainly a concern for consortiums and not for the EU, as traffic can easily go through another path. Google declared in 2014 that they would wrap at least a part of their submarine internet cables, made of fibre, in Kevlar-like material to protect them.[22] This kind of measures, as well as cable burials in the seabed, made that no damaging fish bites were reported over 2007–2014.[23]

- Abrasion. Abrasion mainly happens when there are wave activities, currents, or when cables are laid on rock.[19] It is a more predictable phenomenon, which is why scientists try to identify its conditions and develop protections. It was responsible for 3.7% of cables faults over 1959–2006.[21]

- Natural disasters (volcano eruptions, earthquakes, tsunamis). They mostly happen in geologically unstable areas, which are outside the EU – even though there is a seismic risk in the Balkans, Greece, and Italy. The danger of such events is to break several cables at the same time, making it harder or impossible to circumvent data through another path. Natural disasters especially represent a major threat to island states, because they are geographically more exposed and because they are often poorly connected. Recent examples of massive internet interruptions are Typhoon Morakot (2009) or the 2022 Tonga volcano eruption.

Climate change could constitute a new threat to undersea cables. It is characterised by its uncertainty – scenarios are only assumptions –, and its uneven consequences across the world. First, climate change creates more frequent and more intense storms and hurricanes.[24] These, as well as changes in precipitations, could make the seabed more unstable, which would influence currents and sediments movements. Cables would then be more vulnerable to erosion.[19] However, buried cables would be less or not impacted, if they are buried deep. Second, global warming increases seismic activities,[25] so the EU and its network could become more vulnerable to earthquakes and tsunamis. Last, cable landing stations are also threatened by climate change. Rising sea level will expose them (as well as a part of onshore cables) to floods, while hurricanes could increase power outages.[26] Northwest Europe is among the most exposed landing location to storm surges. However, the EU coastline is one of the least exposed to sea level rise, with sea level at landing stations even projected to lower by 2052.[27]

Involuntary human threats

The biggest cause of submarine internet cables damage is fishing, which accounts for 44.6% of cable faults over 1959–2006.[21] The EU represents 3% of the fisheries and aquaculture production of the world and ranks as its fifth largest one.[28] The most widely used method of fishing, which is also the most damaging to submarine cables, is bottom trawling. It is extremely intense in the English Channel, the Strait of Dover, and the Skagerrak.[29] When the fishing gear is on the sea bottom, it can move the cable or get stuck underneath, eventually breaking it or damaging the waterproof protection and causing court-circuits.[30] This situation is also prejudicial to the fishermen, as such a collision often means loss of fish, time, and damage on their fishing gear.[31] Another damage caused by ships is anchoring, which was responsible for 14.6% of cable damages over 1959–2006.[21] This happens when ships drop anchor right on a cable. Overall, these damages happen in areas where the EU has a really high linkage, so data can easily be circumvented through another route.

Voluntary human threats

Undersea cables are also vulnerable to targeted attacks conducted by humans. Three categories can be distinguished: blue crime, terrorism, and state-sponsored attacks.

Blue crime

Blue crime refers to “serious organised crimes or offences that take place transnationally, on, in or across the maritime domain and cause or have the potential to inflict significant harm”.[32] It is close to the notion of transnational organised crimes at sea. The only aim of blue crime is monetary profit. One form of criminal activity against submarine cables is cable theft. An example is the cable between Singapore and Indonesia, which was partly robbed in 2013: 31,7 km and 418 tons of cables were removed.[33] Another scenario is a criminal group threatening to harm cables if no ransom is received. Last, cables could be damaged to cover an unrelated criminal attack, as it would diminish surveillance capacities.[34]

Terrorism

Terrorism is close to blue crime, except that its aim is political and not monetary. For now, no terrorist attack against submarine cables have been recorded.[35] Attacks could consist in targeting landing stations,[34] or dragging an anchor on the seabed in an area of high cable density.[35] However, the probability of a blackout in the EU or in one of its Member States is low, as it would require precision and coordination. Besides, terrorists themselves rely on internet cables to communicate, and to spread terror to the public,[34] so it is not in their interest to damage the whole network. Risks are higher for remote islands with less connectivity, such as EU Member States’ naval bases abroad (like in Djibouti), EU Islands, or Member States’ oversea territories (like La Réunion, which possesses 3 submarine cables[4]).

State-led attacks

To date, no attack on submarine internet cables has been attributed to a State. However, the attack of the gas pipeline Nord Stream II in 2022, presumably United States-sponsored, underlines that this kind of sabotage is possible. Overall, the shadow of these attacks is part of hybrid threats. The EU defines them as: “when actors seek to exploit the vulnerabilities of the EU to their own advantage by using a mixture of measures (i.e. diplomatic, military, economic, technological) while remaining below the threshold of formal warfare".[36] The greatest fear is hence that submarine internet cables vandalism might be used as part of a coordinate attack targeting other key infrastructures, like cyberspace. Despite Sweden and Denmark's lack of finding a culprit, Russia is often thought to have been involved in the Nords Stream sabotage due to the tensions with the EU and the presence of Russian ships around it days prior.[37] Russia has previously been associated with strategies such as the spread of fake news,[38] the sponsor of cyberattacks,[39] and navigation close to key EU infrastructures.[40] For example, in February 2022, Russia did a military exercise at the border of Ireland's EEZ, near undersea internet cables. An Irish officer notes "the intention is not to cut the cables but to send a message [to NATO] that they can cut them anytime they want".[34] However, the principle of hybrid threats is that attacks, when they happen, are non-attributable.

Another concern is China's ubiquity in the submarine internet cables network. 100 out of 400 global internet cables are managed or have been built by HMN Technologies, which also possesses 10% of market shares.[34] This gives China power over the current and upcoming infrastructure, but also gives it a potential for data interception.[41]

Protection

Physical

The EU lets the cables and fishery industries regulate themselves. It is about "talking to each other to raise awareness" or "changing the design of fishing gear".[31] However, the EU facilitates dialogue through its European Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP) platform. It is also thinking about pushing for cable routes/corridors, or developing no-anchor/no-trawl zones.[30] It could also require cables to cross shipping lanes by the shortest route possible, and/or to be buried.[31]

EU protection measures especially target intentional damage, particularly state-sponsored hybrid threats. There is however no piece of legislation from the EU that only deals with submarine internet cables.

Cables are the competency of Member States.[14] However, monitoring cables is very challenging and requires significant resources. States therefore seek for a "Union-wide coordinated approach to strengthen the resilience of critical infrastructure".[42] The EU complements their action, by upgrading risk assessments and responses.[14]

The EU has a European Programme for Critical Infrastructure Protection (EPCIP), which was last updated in 2013. Additional measures for Critical Infrastructure protection were on the EU Commission’s agenda in 2020.[43] Today, the EPCIP is complemented by other legal frameworks. Submarine internet cables protection is dealt with in the European Union Maritime Security Strategy (EUMSS).[44] The 2018 EUMSS already sought to enhance the critical infrastructures’ resilience, via risk assessment and management, and education and training.[45] The 2023 update implements common military exercises among voluntary Member States, to better address hybrid threats, both at sea and on land. The goal is to improve "both the physical and cyber resilience of critical entities and infrastructures".[46] The link between undersea cables and cyberspace is now more widely recognized. Internet cables are also mentioned in the NIS 2 directive, which deals with EU cybersecurity. It expects each State to issue a national cybersecurity strategy (which includes cable protection), and report issues to the European level.[47] In addition, by January 17, 2026, Member States should have drawn a list of critical entities for each recognized sector, and build up a national strategy for critical infrastructure protection.[48]

The EU also wants to enhance cooperation with its allies, particularly the US and NATO, in terms of information exchange and surveillance. The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats is one of their knowledge-building collaboration measures, in the area of hybrid threats. An EU-NATO Task Force was also created in March 2023 to work on critical infrastructure resilience (energy, transports, digital infrastructure, and space).[49] However, “technological sovereignty” is one of EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s top priorities for her mandate (2019–2024).[10] The EU will aim at being ore independent from its allies such as the USA. The 2013 leak of pieces of US intelligence revealed that the USA were spying on their allies, while at that time 80–85% of data traffic between the EU and Latin America was going through North America.[50] Brazil and the EU created EllaLink because of this event.

Human Rights

Recently, debates have risen regarding access to communication. Arguments state that the world has become too connected and dependent on internet to avoid needing it. Internet is important for emergency issues, to be able to communicate if something happens.[51] It is compared to other rights under the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights such as freedom of speech and, most importantly, the right to health and to communicate emergencies.[51] Protection of cables are, then, not just a duty to protect access to internet but one to protect Human Rights.[51] With 8% of the population with no access to internet in 2021, the rapid development of internet is an act to protect those rights.[52]

See also

References

- ↑ Nystro, M., Jouffray, J.B., Blasiak, R., & Norstro, A.V. (2020). The Blue Acceleration: The Trajectory of Human Expansion into the Ocean. One Earth, 2(1), p43–54.

- ↑ Guilfoyle, D., Paige, T., & McLaughlin, R. (2022). The final frontier of cyberspace: the seabed beyond national jurisdiction and the protection of submarine cables. International & Comparative Law Quarterly, 71(3), p657-696.

- ↑ World Bank. (2021). Individuals using the internet. Accessed: 03 May 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 TeleGeography. Submarine cable map. Accessed: 04 May 2023.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Bueger, C., Liebetrau, T., & Franken, J. (2022, June). Security threats to undersea communications cables and infrastructures – consequences for the EU. EU Parliament.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Burnett, D.R., Beckman, R., & Davenport, T.M. (2013). Submarine Cables: the Handbook of Law and Policy. Brill, p74-88.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Davenport, T. (2015). 'Submarine Communications Cables and Science: A new Frontier in Ocean Governance?', in Scheiber, H., Kraska, J., Kwon, M. (eds). Science, Technology, and New Challenges to Ocean Law. Brill

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Wall, C., Morcos, P. (2021, June 11). 'Invisible and Vital: Undersea Cables and Transatlantic Security'

- ↑ You, Y. (2011). 'Using Submarine Communications Networks to Monitor the Climate – an ITU-T Technology Watch Report"

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Claessen, E. (2020). Reshaping the internet – the impact of the securitisation of internet infrastructure on approaches to internet governance: the case of Russia and the EU, Journal of Cyber Policy, 5(1), p140-157.

- ↑ Bueger, C., Liebetrau, T., Franken, J. (2022, June). 'Security threats to undersea communications cables and infrastructure – consequences for the EU. European Parliament

- ↑ Long, R. (2015). "A European Law Perspective: Science, Technology, and New Challenges to Ocean Law". In: Scheiber, H., Kraska, J., Kwon, M-S. (2015). Science, Technology, and New Challenges to Ocean Law.

- ↑ Facts and figures on the common fisheries policy: Basic statistical data : 2022. Publications Office of the European Union. 2022. ISBN 978-92-76-42605-9. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c2f39f4a-29a2-11ed-975d-01aa75ed71a1#.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 ENISA. (2023, July). 'Subsea Cables – What is at stake?'

- ↑ Raha, U. K., Raju, K. D. (2021). Submarine Cables Protection and Regulations: A Comparative Analysis and Model Framework.

- ↑ Council of the European Union. (2008, December 8). Council directive 2008/114/EC of 8 December 2008 on the identification and designation of European critical infrastructures and the assessment of the need to improve their protection. Annex I.

- ↑ European Commission. (2012, June 22). Commission staff working document on the review of the European Programme for Critical Infrastructure Protection (EPCIP)

- ↑ European Commission. Critical infrastructure protection. Accessed: 20 May 2023.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 ICPC, UNEP. (2009). Submarine cables and the oceans: connecting the world. p30, p39-41.

- ↑ Márquez, M.C. (2020, July 20). Our underwater world is full of cables… that are sometimes attacked by sharks. Forbes. Accessed: 10 May 2023.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Sunak, R. (2017). Undersea cables. Indispensable, insecure. Policy exchange. p21.

- ↑ Butler, B. (2014, August 13). Google wraps its trans-Pacific fiber cables in Kevlar to prevent against shark attacks. Network World. Accessed: 10 May 2023.

- ↑ International Cable Protection Committee. (2015, July 1). Sharks are not the Nemesis of the internet – ICPC findings

- ↑ Colbert, A. (2022, June 1). 'A force of Nature: Hurricanes in a Changing Climate'

- ↑ McGuire, B. in Climate change risks triggering catastrophic tsunamis, scientist warns. (2021). Financial Times.

- ↑ Clare, M. A. et alt. (2023, February). 'Climate change hotspots and implications for the global subsea telecommunications network'

- ↑ Clare, M. (2023, May). Submarine Cable Protection and the Environment. ICPC. Issue No. 6.

- ↑ European Commission. (2022). 'Facts and figures on the common fisheries policy – Basic statistical data'

- ↑ Eigaard et al. (2017) in European MSP Platform. Conflict fiche 2: Cables/pipelines and commercial fisheries/shipping. p4.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 MSP. (2021, February 23). 'Cables and fisheries'

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 European MSP Platform. Conflict fiche 2: Cables/pipelines and commercial fisheries/shipping.

- ↑ Bueger, C., & Edmunds, T. (2020, September). Blue crime: conceptualising organised crime at sea. Marine Policy, 119, 104067.

- ↑ The Jakarta Post. (2013, July 08). Ministry sets up submersible cable task force. Accessed: 15 May 2023.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 Bueger, C., Liebetrau, T., & Franken, J. (2022, June). Security threats to undersea communications cables and infrastructures – consequences for the EU. EU Parliament. p31-34.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Burnett, D.R., Beckman, R., & Davenport, T.M. (2013). Submarine Cables: the Handbook of Law and Policy. Brill.

- ↑ European Commission. Hybrid Threats. Accessed: 15 May 2023.

- ↑ Camut, N. (2023, April 28)'Russian ship spotted near Nord Stream pipelines days before sabotage: Reports'

- ↑ Spidsboel Hansel, F. (2017).'Russian hybrid warfare: A study of disinformation'

- ↑ Cynersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency. (2022, May 09). 'Russian State-Sponsored and Criminal Cyber Threats to Critical Infrastructure'

- ↑ Siebold, S. (2023, May 03), 'NATO says Moscow may sabotage undersea cables as part of war on Ukraine

- ↑ Burdette, L. (2021, May 5). 'Leveraging Submarine Cables for Political Gain: U.S. Responses to Chinese Strategy'

- ↑ Council of the European Union. (2022, December 08). Council Recommendation 2023/C 20/01 on a Union-wide coordinated approach to strengthen the resilience of critical infrastructure

- ↑ European Commission. (2020). Commission Work Programme 2020. Annex 1, p4.

- ↑ Council of the European Union. (2018, June 26). Council conclusions on the revision of the European Union Maritime Security Strategy Action Plan

- ↑ Council of the European Union. (2018, June 26). Council conclusions on the revision of the European Union Maritime Security Strategy (EUMSS) Action Plan. p18, p21.

- ↑ European Commission. (2023, March 10). Joint communication to the European Parliament and the Council on the update of the EU Maritime Security Strategy and its Action Plan "An enhanced EU Maritime Security Strategy for evolving maritime threats". p11.

- ↑ European Parliament, & Council of the European Union. (2022, December 14). Directive (EU) 2022/2555 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union, amending Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 and Directive (EU) 2018/1972, and repealing Directive (EU) 2016/1148 (NIS 2 Directive)

- ↑ European Parliament, & Council of the European Union. (2022, December 14). Directive (EU) 2022/2557 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on the resilience of critical entities and repealing Council Directive 2008/114/EC

- ↑ NATO. (2023, March 16). NATO and European Union launch task force on resilience of critical infrastructure. Accessed: 16 May 2023.

- ↑ Lazarou, E. (2015). EU-Brazil cooperation on internet governance and ICT issues. European Parliamentary Research Service.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Kirchner, S. (2020). 'Mobile Internet Access as a Human Right: A View from the European High North'. in: Salmien, M., Zojer, G., Hossain, K. (eds). Digitalisation and Human Security: New Security Challenges. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ↑ Jacobs, F. (2023, January 26). ' Europe's stunning digital divide, in one map'

|