Engineering:Humanitarian Logistics

Although logistics has been mostly utilized in commercial supply chains, it is also an important tool in disaster relief operations. Humanitarian logistics is a branch of logistics which specializes in organizing the delivery and warehousing of supplies during natural disasters or complex emergencies to the affected area and people. However, this definition focuses only on the physical flow of goods to final destinations, and in reality, humanitarian logistics is far more complicated and includes forecasting and optimizing resources, managing inventory, and exchanging information. Thus, a good broader definition of humanitarian logistics is the process of planning, implementing and controlling the efficient, cost-effective flow and storage of goods and materials, as well as related information, from the point of origin to the point of consumption for the purpose of alleviating the suffering of vulnerable people.[2]

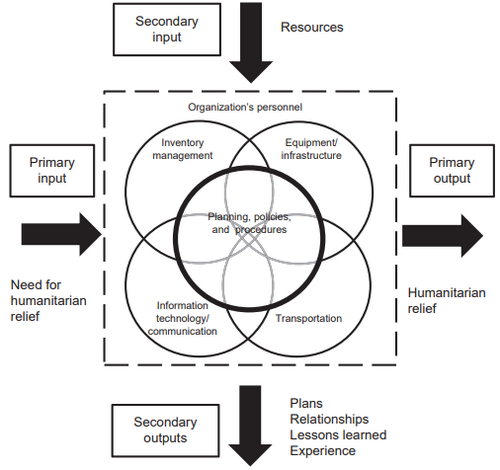

This figure presents numerous important aspects in humanitarian logistics, including transport, inventory management, infrastructure, and communications.

The role of humanitarian logistics in disaster relief efforts

Humanitarian logistics plays an integral role in disaster relief for several reasons. First, humanitarian logistics contributes immensely to mitigating the negative impact of natural disasters in terms of loss of life and economic costs. These losses occur in four different ways:

- Losses of buildings, highways and other infrastructure;

- Losses in output and reductions in employment and tax receipts;

- Losses due to the increase in the price of consumable and construction materials; and

- Losses of millions of lives because of the scarcity of food and accidents.[3]

Second, humanitarian logistics is considered the repository of data that can be analyzed to provide post-event learning. Logistics data reflects all aspects, from the effectiveness of suppliers and transportation providers, to the cost and timeliness of response, to the appropriateness of donated goods and the management of information. Thus, it is critical to the performance of both current and future operations and programs. Organizing emergency response plans will help preparation and consequently mobilization in times of disasters.[4][5]

The process of humanitarian logistics

As can be seen in the above Figure, the process is complicated with the involvement of various actors in different locations. To be more specific, the process connects various actors, including, donors, local/international aid organizations, local governments, and beneficiaries. There are three fundamental flows in this process: the flow of material, the flow of money, and the flow of information.

- The flow of material: the flow of products from donors to beneficiaries, including food, blankets, medicines, and water, and the reverse flow of returned products after disasters.

- The flow of information: includes demand forecasts, order transmissions, and order status reports, to ensure preparedness and communications.

- The flow of money: includes checks, cash, and payment documents such as Letters of credit, invoice, and commercial contracts.[7][8]

Storage

Developing logistics warehousing to store all essential goods plays a crucial role in disaster response planning. Warehouses should be designed by taking precautions for contamination or waste of materials and organized in order to facilitate deliveries to the desired area at the desired time and quantities. In addition, responsible authorities aim at maximizing responsiveness and minimizing distribution times, total costs, and the number of distribution centers. The entire storage process is of key importance for preserving emergency supplies until they can be delivered to recipients.[9]

Types of warehouse

Humanitarian Warehouses can be categorized into four main types, depending on their functions and locations.

- General Delivery Warehouses: where products are stored for a long time (e.g., months or quarters) or until they are sent to secondary warehouses or distributed in the field. General delivery warehouses are more common in the capital of beneficiary or donor countries or at strategic points of a given region (based on forecasts).[10]

- Slow Rotation Warehouses: where non-urgent or reserve stockpiles are kept, including goods that are not in frequent demand such as spare parts, equipment, and tools.[10]

- Quick Rotation Warehouses: where emergency supplies quickly move in and out, on a daily or at most weekly basis. Such warehouses are situated near the heart of affected zones and hold items that require prompt distribution among the affected population, including food, blankets, and hygiene items.[10]

- Temporary Collection Sites: where incoming supplies are stored until a more appropriate space can be found. Temporary collection sites include yards, offices, meeting rooms, and garages of disaster relief organizations.[9]

Humanitarian Warehouses can also be classified as perishables warehouses or 3PL warehouses.[13] However, it is common in humanitarian logistics to have four types of warehouses as mentioned above. Depending on the magnitude of disasters and the urgency, a certain type of warehouses is needed. For example, for unexpected disasters, temporary warehouses are more common than others. In contrast, for planned disasters, general delivery warehouses are needed to store products in beneficiary countries.

Choices of warehouses

When selecting an appropriate site to store goods, two considerations are important:

- Type of supplies: Pharmaceutical products and foods require a well-ventilated, cool, dry place. Some of these products may even need temperature control. Other items, such as clothing or equipment, have more flexible requirements.

- Size and access to warehouses: the size of the storage site is significantly important. One must take into account not just its current capacity but also the potential for expansion of the storage area. Accessibility is another key issue, particularly for large vehicles.

Inventory management

A logistical technique which can improve responsiveness is inventory pre-positioning. This technique is used for estimating item quantities required according to specific safety stock levels and order frequency, or for searching optimal locations for warehouses using facility location. Logistics is one of the major tools of disaster preparedness, among surveillance, rehearsal, warning, and hazard analysis. There are four primary types of inventory planning:

- Single-period inventory model/News-vendor model

- Base-stock model

- Periodic review model

- Dynamic lot-size model

Each model has different advantages and disadvantages; therefore, it is important for inventory planners to consider all aspects, including total holding costs, service level, and demand variability, to have an efficient strategy.

Transport

Transport plays a key role in mobilizing supplies to help emergency humanitarian assistance reach affected regions. In humanitarian logistics, it is important to determine the feasibility of various forms of transport on the basis of the level of urgency, total costs, and geographical characteristics of affected zones.

Characteristics of different means of transport

| Types of transport | Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air (Airplanes)[14] | Used when supplies are needed urgently,

or when there is no other way to reach the affected area. |

|

|

| Air (Helicopters)[10] | More versatile than planes |

|

|

| Land (motor vehicles)[10] | Depends mainly on the physical and safety conditions of the access routes to the delivery points. |

|

|

| Land (rail)[15] | Depends on the existence and route of the railroad and its condition |

|

|

| Maritime[15] | Used mostly for transporting supplies from abroad. Requires access to a harbor or pier. |

|

|

| River[10] | Useful for supplying riverside and nearby communities with moderate amounts of emergency aid, or for moving people and supplies in the event of a flood. |

|

|

| Intermodal[15] | A combination of at least two means of transport, with the most common being truck/rail. |

|

|

| Human and animal[10] | Used for small loads, generally in remote areas or places (horses or camels). |

|

|

Considerations of different means of transport

When planning the type and capacity of transport, five major considerations are crucial:

- The nature of supplies to be transported: Different categories of products requires different handling methods as well as temperature control. For example, hazardous materials must be stored separately from pharmaceutical products and food.[10]

- The weight and volume of the load: Both are critical factors that determine the capacity of vehicles and the type of transport.[10]

- The destination: distance, form of access to the delivery point (by air, water, or land). This factor should be taken into consideration because mobilizing the goods from the ports to the final destinations is often constrained by poor local infrastructure and unexpected events such as floods, landslides, and storms.[16]

- The urgency of the delivery: In most emergency situations, needed goods, particularly food and fuels, are sent by air to destinations although this option is expensive. In humanitarian logistics, the priority is to save more lives.[17]

- Alternative means, methods, and routes: Depending on one option represents a risk, especially there are some force majeure.[10]

The below table provides a simple formula to help planners forecast transport demand during a disaster. There are three main components: the number of trips for a vehicle, the volume, and the total number of vehicles.

| Calculation procedure | Formula |

|---|---|

| Number of possible trips per vehicle | |

| Number of loads | |

| Number of vehicles |

Types of transport contracts

There are three primary types of transport contracts. Each type has distinct advantages and disadvantages.

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| By the ton or ton/km[19] |

|

|

| Per vehicle per journey[19] |

|

|

| Per vehicle per day[19] |

|

|

New technologies in humanitarian logistics

Technology is a key factor to achieve better results in disaster logistics. Implementing up-to-date information or tracking systems and using humanitarian logistics software which can provide real-time supply chain information, organizations can enhance decision making, increase the quickness of the relief operations and achieve better coordination of the relief effort. Biometrics for identifying persons or unauthorized substances, wireless telecommunications, media technology for promoting donations, and medical technologies are some more aspects of technology applied in humanitarian operations. There are three main developments in this field: bar codes, AMS laser cards, and radio frequency tags.

AMS Cards

Automated manifest system (AMS) cards have been used by the United States government to store substantial amounts of information about shipments. The cards have become more popular in humanitarian logistics as they are able to provide various aspects related to:

- Stock number;

- Requisition number;

- Shipment date;

- Quantity;

- Consignee.

The AMS cards are attached to both pallets and containers and inserted to a processing unit which can give all details about a delivery. The use of those cards is beneficial to both shippers and beneficiaries in humanitarian logistics management because beneficiaries can plan resources, especially food and medicines, or find alternatives. Therefore, this application can make the process more flexible and efficient. In addition, AMS cards are cheap, reusable, and resistant to extreme weather.[10]

Radio Frequency Identification Tags and Labels

The tags are useful in identifying information about delivery routes. They are attached to different types of vehicles, including pallets, trucks, vans, and large containers, to position the location of shipments en route. In addition, they can read information when the vehicles pass through points along the route. After that, the information is stored on a label. Together with the AMS cards, they can provide an effective solution to humanitarian logistics to increase its transparency and responsiveness.[20]

Bar Codes

One major concern in humanitarian logistics management is the reliability of product sources because the most popularly-procured item is food. In the past, there were cases regarding food unsafety caused by the unclear origins of products. Recently, bar codes have been a feasible solution to address this problem in humanitarian logistics. Bar code labels make it possible to represent alphanumeric characters (letters and numbers) by means of bars and blanks of varying widths that can be read automatically by optical scanners. This system recognizes and processes these symbols, compares their patterns with those already stored in computer memory, and interpret the information. This standardized coding system means that there can be a one-on-one, unique, non-ambiguous relationship between the pattern and that to which it refers. At present, bar codes are mostly used in:

- Product packages;

- Identification cards;

- Catalogs or price lists;

- Product labels;

- Forms, receipts, and invoices.[10]

References

- ↑ Overstreet, Robert E.; Hall, Dianne; Hanna, Joe B.; Kelly Rainer, R. (2011-10-21). "Research in humanitarian logistics" (in en). Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management 1 (2): 114–131. doi:10.1108/20426741111158421. ISSN 2042-6747.

- ↑ Thomas, Anisya (2005). From Logistics to Supply Chain Management: The Path Forward in the Humanitarian Sector. USA: Fritz Institute.

- ↑ Alexander, David (1993). Natural disasters. London: UCL Press. ISBN 1857280938. OCLC 30508919.

- ↑ Gupta, Shivam; Altay, Nezih; Luo, Zongwei (2017-11-16). "Big data in humanitarian supply chain management: a review and further research directions" (in en). Annals of Operations Research 283 (1–2): 1153–1173. doi:10.1007/s10479-017-2671-4. ISSN 0254-5330. https://works.bepress.com/nezih_altay/39.

- ↑ Monaghan, Asmat; Lycett, Mark (16 January 2014). "Big data and humanitarian supply networks: Can Big Data give voice to the voiceless?". 2013 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC) – 20-23 Oct 2013 – San Jose, CA. IEEE. doi:10.1109/ghtc.2013.6713725.

- ↑ İlhan, Ali (2011-11-01). "The Humanitarian Relief Chain". South East European Journal of Economics and Business 6 (2): 45–54. doi:10.2478/v10033-011-0015-x. ISSN 1840-118X.

- ↑ SUNYOTO, USMAN (2006). "DEVELOPING HUMANITARIAN LOGISTIC STRATEGY: AN INTERSECTIONIST VIEW". Asia Pacific Whitepaper Series 12. http://www.tliap.nus.edu.sg/pdf/whitepapers/12-Nov-SCI06_Developing%20Humanitarian%20Logistics%20Strategy.pdf.

- ↑ Heaslip, Graham; Kovács, Gyöngyi; Haavisto, Ira (2018-04-03). "Cash-based response in relief: the impact for humanitarian logistics" (in en). Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management 8 (1): 87–106. doi:10.1108/JHLSCM-08-2017-0043. ISSN 2042-6747.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 SUNYOTO, USMAN (2006). "DEVELOPING HUMANITARIAN LOGISTIC STRATEGY: AN INTERSECTIONIST VIEW". Asia Pacific Whitepaper Series 12. http://www.tliap.nus.edu.sg/pdf/whitepapers/12-Nov-SCI06_Developing%20Humanitarian%20Logistics%20Strategy.pdf.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 Humanitarian supply management and logistics in the health sector. Pan American Health Organization. Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Relief Coordination Program.; World Health Organization. Division of Emergency and Humanitarian Action.. [Washington, D.C.]: Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Relief Program, Pan American Health Organization; [Geneva]: Dept. of Emergency and Humanitarian Action, Sustainable Development and Healthy Environments, World Health Organization. 2001. ISBN 9789275123751. OCLC 50476856.

- ↑ "Dubai: global hub for relief" (in en). https://gulfnews.com/opinion/op-eds/dubai-global-hub-for-relief-1.1079410.

- ↑ "Temporary Buildings - Storage, Logistics & Manufacturing" (in en-GB). https://www.coprisystems.com/industrial/storage/.

- ↑ Ribbons, John. "Warehouse and Distribution Science". Georgia Institute of Technology. https://www2.isye.gatech.edu/~jjb/wh/book/editions/wh-sci-0.96.pdf.

- ↑ Nedeva, Keranka; Genchev, Evgeni (2018-10-01). "Air Transport - A Source of Competitive Advantages of the Region". Marketing and Branding Research 5 (4): 206–216. doi:10.33844/mbr.2018.60246. ISSN 2476-3160.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Chopra, Sunil; Meindl, Peter (2016). Supply chain management : strategy, planning, and operation (6th ed.). Boston. ISBN 9780133800203. OCLC 890807865.

- ↑ Zhang, MS, Han; Strawderman, PhD, Lesley; Eksioglu, PhD, Burak (2011-01-01). "The role of intermodal transportation in humanitarian supply chains". Journal of Emergency Management 9 (1): 25. doi:10.5055/jem.2011.0044. ISSN 1543-5865.

- ↑ "Global Shipping: Choosing the Best Method of Transport". https://wir-en.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Global-Shipping-Methods1.pdf.

- ↑ Davis, Jan; Lambert, Robert (2002). Engineering in emergencies : a practical guide for relief workers. Red R (Organization) (2nd ed.). London: ITDG. ISBN 1853395218. OCLC 49758116.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (1997). Handbook for Delegates. Geneva: IFRC.

- ↑ Zhang, Xiaoqiang; Dong, Qin; Hu, Fangjie (2012-11-08). "Applications of RFID in Logistics and Supply Chains: An Overview". Iclem 2012 (Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers): 1399–1404. doi:10.1061/9780784412602.0213. ISBN 9780784412602.

Further reading

- Blanco, Edgar E.; Goentzel, Jarrod (2006). Humanitarian supply chains: a review. MIT Center for Transportation & Logistics, POMS.

- Iqbal, Qamar; Mehler, Kristin; Yildirim, Mehmet Bayram (2007). "Comparison of Disaster Logistics Planning and Execution for 2005 Hurricane Season". InTrans Project Reports 167. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/intrans_reports/167.

- Margaret O'Leary, 2004. Measuring disaster preparedness: a practical guide to indicator, iUniverse, ISBN 978-0-595-53170-7

- Kevin Cahill, 2005, Technology for humanitarian action, Fordham Univ Press, ISBN 978-0-8232-2394-7

- Anup Roop Akkihal (2006). Inventory pre-positioning for humanitarian operations.

- Anne Leslie Davidson (2006). Key performance indicators in humanitarian logistics.

- Martin Christopher and Peter Tatham, 2011, Humanitarian Logistics: Meeting the Challenge of Preparing for and Responding to Disasters, Kogan Page, ISBN 0749462469, ISBN 978-0749462468

- Karen Spens and Gyöngyi Kovacs, 2010, Back to basics - is logistics again about cutting costs?, http://lipas.uwasa.fi/~phelo/ICIL_2010_Proceedings_Rio.pdf

- Tatham, Peter; Kovács, Gyöngyi (2010). "The application of "swift trust" to humanitarian logistics". International Journal of Production Economics 126: 35–45. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2009.10.006.

- Kovács, Gyöngyi; Spens, Karen (2009). "Identifying challenges in humanitarian logistics". International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 39 (6): 506. doi:10.1108/09600030910985848.

External links

- Humanitarian Logistics Research at MIT Center for Transportation & Logistics

- The Center for Health & Humanitarian Systems at Georgia Tech (formerly Health & Humanitarian Logistics)

- The Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Research Institute (HUMLOG) at HANKEN School of Economics (Helsinki, Finland)

- Humanitarian Logistics in Emergencies training at RedR Australia