Engineering:Irene-class cruiser

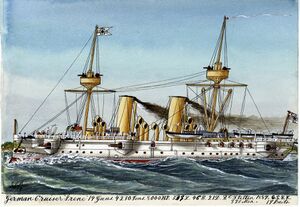

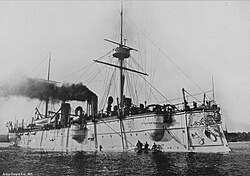

SMS Irene at full steam.

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Irene class |

| Builders: | AG Vulcan Stettin and Germaniawerft, Kiel |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | None |

| Succeeded by: | Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist. |

| Built: | 1886–1889 |

| In service: | 1888–1922 |

| Completed: | 2 |

| Retired: | 2 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Protected cruiser |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 103.70 m (340 ft 3 in) oa |

| Beam: | 14.20 m (46 ft 7 in) |

| Draft: | 6.74 m (22 ft 1 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range: | 2,490 nmi (4,610 km; 2,870 mi) at 9 knots (17 km/h; 10 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

The Irene class was a class of protected cruisers built by the Imperial German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) in the late 1880s. The class comprised two ships, Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist. and Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist.; they were the first protected cruisers built by the German Navy. As built, the ships were armed with a main battery of fourteen 15 cm (5.9 in) guns and had a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). They were modernized in 1899–1905, and their armament was upgraded with new, quick-firing guns.

Both ships served in the East Asia station with the East Asia Squadron; Prinzess Wilhelm played a major role in the seizure of the Jiaozhou Bay Leased Territory in November 1897. Both ships returned to Germany at the turn of the 20th century, and remained in European waters until 1914, when they were removed from active service. They were reduced to secondary roles then, and continued to serve until the early 1920s, when they were sold for scrap.

Design

In 1883, General Leo von Caprivi became the Chief of the Imperial Admiralty, and at the time, the pressing question that confronted all of the major navies was what type of cruiser to build to replace the obsolete rigged screw corvettes that had been built in the 1860s and 1870s. Cruisers could be optimized for service with the main fleet or for deployments abroad, and while the largest navies could afford to build dedicated ships of each type, Germany could not. The Reichstag (Imperial Diet) would not provide funding for such types. Furthermore, the navy had completed the cruiser construction program under the fleet plan of 1873 with the screw corvette Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist., which removed Caprivi's ability to use an approved fleet plan to justify further cruisers. The previous practice of building rigged corvettes for overseas use and avisos for fleet defense against small craft would no longer be tenable.[1][2]

Despite the Reichstag's reluctance to fund new warships, many of the fleet's oldest cruising vessels were in need of replacement; the next scheduled to be replaced was the old screw frigate Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist.. Caprivi initially requested funding to replace the ship in 1883, which the Reichstag rejected. Caprivi, a general whose career had been spent in the Imperial German Army, created an Admiralty Council on 16 January 1884 to advise him, and the particulars of the next cruiser to be built was among the topics discussed. The council recommended a ship with the following characteristics: sufficient seaworthiness to permit operations in all sea and climate conditions; enough speed to catch or evade likely opponents; cruising radius necessary for long-range operations; and gun power strong enough to defeat expected opponents, but not to exceed 5 to 8% of the ship's displacement. The council discussed the matter over the course of several meetings in January, which Caprivi recorded in a memorandum dated 11 March. The document, which laid out Caprivi's thoughts on future naval construction in general, included requirements for 1st- and 2nd-class cruisers.[3]

As work began on refining the proposals, the council set displacement at 3,500 t (3,400 long tons; 3,900 short tons) for the 1st-class variant, armament as a main battery of 15 cm (5.9 in) guns along with three torpedo tubes, speed was to be 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph), and the cruising radius must meet a minimum of 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi). A 2nd-class version was also created on a displacement of 2,200 t (2,200 long tons; 2,400 short tons), with scaled down specifications in all other categories. The fleet's chief designer, Alfred Dietrich, set about turning these broad parameters into a proper design, but he quickly determined that no ship could be built to those specifications on the allotted displacement. He enlarged the 1st-class design significantly and increased displacement to 4,300 t (4,200 long tons; 4,700 short tons), and completed the design on 28 April 1885. Caprivi approved the plans on 1 May.[4]

The historians Hans Hildebrand, Albert Röhr, and Hans-Otto Steinmetz remark that the new ships had "all the disadvantages of a compromise," and that they would not prove suitable as a fleet cruiser.[5] Dirk Nottelmann concurred, noting that the ships "were neither well suited for fleet work nor for the increasing tasks in distant waters, like has been the case for most dual-purpose designs until today."[6]

General characteristics

The ships were 98.90 m (324 ft 6 in) long at the waterline and 103.70 meters (340 ft 3 in) long overall. They had a beam of 14.20 m (46 ft 7 in) and a draft of 6.74 m (22 ft 1 in) forward. They displaced 4,271 metric tons (4,204 long tons) at designed displacement and 5,027 t (4,948 long tons) at full load. The hull was constructed with transverse and longitudinal steel frames, and the outer hull consisted of wood planking covered with Muntz copper sheathing to prevent fouling. The stem was made of bronze below the waterline and iron above. The hull was divided into ten watertight compartments and had a double bottom that extended for 49 percent of the length of the hull.[7]

The ships were very good sea boats; they ran very well before the wind, and were very handy. They lost minimal speed in hard turns and suffered from moderate roll and pitch. In heavy seas, the ships were capable of only half speed, as both suffered from structural weakness in the forecastle. They had a transverse metacentric height of .69 to .72 m (2 ft 3 in to 2 ft 4 in). The ships had a crew of 28 officers and 337 enlisted men. The ships carried a number of smaller boats, including two picket boats, one pinnace, two cutters, one yawl, and two dinghies. Searchlight platforms were added to the foremast 13 m (42 ft 8 in) above the waterline.[8]

Machinery

Irene's propulsion system consisted of two horizontal, 2-cylinder double-expansion steam engines that drove a pair of screw propellers. The engines needed to be arranged horizontally to fit them under the ship's deck armor. The engines were divided into their own engine rooms. Irene was equipped with a pair of three-bladed screws 4.50 m (14 ft 9 in) in diameter; Prinzess Wilhelm had slightly larger 4.70 m (15 ft 5 in) screws with four blades. Steam was provided by four coal-fired fire-tube boilers, which were ducted into a pair of funnels. Irene's engines were manufactured by Wolfsche, while AG Germania produced those for Prinzess Wilhelm. The ships were equipped with a pair of electrical generators that produced 23 kilowatts (31 hp) at 67 volts. Prinzess Wilhelm was later equipped with three generators with a combined output of 33 kW (44 hp) at 110 volts. Steering was controlled by a single rudder.[9][10]

The ships' engines were rated at 8,000 metric horsepower (7,900 ihp) and provided a top speed of 18 kn (33 km/h; 21 mph), though on trials, Irene reached a maximum of 18.1 knots (33.5 km/h; 20.8 mph), while Prinzess Wilhelm made 18.5 knots (34.3 km/h; 21.3 mph). The ships had a range of approximately 2,490 nautical miles (4,610 km; 2,870 mi) at a cruising speed of 9 kn (17 km/h; 10 mph). Despite the original requirement to be able to steam for 5,000 miles, Dietrich had been unable to significantly increase the coal storage when he enlarged the design. Additionally, the Wolfsche engines were notoriously inefficient. Worse still, the horizontal arrangement limited the piston stroke, which further reduced their efficiency.[9][11]

Armament and armor

The ships were armed with a main battery of four 15 cm RK L/30 guns in single pedestal mounts, supplied with 400 rounds of ammunition in total. These guns were placed in sponsons on each quarter. They had a range of 8,500 m (9,300 yd). The ships also carried ten shorter-barreled 15 cm RK L/22 guns in single mounts. These guns had a much shorter range, at 5,400 m (5,900 yd).[8] The gun armament was rounded out by six 3.7 cm revolver cannon, which provided close-range defense against torpedo boats.[12] They were also equipped with three 35 cm (13.8 in) torpedo tubes with eight torpedoes, two launchers were mounted on the deck and the third was in the bow, below the waterline.[8][10]

The ships were protected with compound steel armor. The armor deck consisted of two layers; on the flat, the layers were 20 mm (0.79 in) and 30 mm (1.2 in) thick, for a total thickness of 50 mm (2 in). On the sides, the deck sloped downward and increased in thickness to 20 mm and 55 mm (2.2 in), totaling 75 mm (3 in) of protection. The coaming was 120 mm (4.7 in) thick and was backed with 200 mm (7.9 in) thick teak. The conning tower had 50 mm thick sides and a 20 mm thick roof. The ships were equipped with cork cofferdams to contain flooding in the event of damage below the waterline.[9]

Modifications

The ships were modernized in Wilhelmshaven between 1892 and 1893. The ships' armament was significantly improved; the four L/30 guns were replaced with 15 cm SK L/35 guns with an increased range of 10,000 m (11,000 yd). Eight 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/35 quick-firing (QF) guns were installed in place of the L/22 guns, and six 5 cm (2 in) SK L/40 QF guns were added.[13] The latter were placed in pairs, two on the stern, two amidships, and the other two on either side of the foremast.[14] The alterations to the ships' guns allowed the number of officers to be reduced to 17, though enlisted ranks increased to 357.[8] Some equipment was removed in an effort to reduce the ship's excessive weight, including anti-torpedo nets, an auxiliary boiler, the steam winch used to hoist the ship's boats, and other miscellaneous equipment. Both ships had their funnels increased in height. Irene also had her bulwarks lowered and her anchor chains altered.[15]

After returning from East Asia in 1899, Prinzess Wilhelm received a minor refit that included increasing coal storage capacity, which came at the expense of a two-thirds' reduction in the magazine capacity for the 15 cm guns. She also had a searchlight installed on her foremast. The work was carried out between 1903 and 1905. Despite reports to the contrary, Irene was not similarly refitted at that time.[16]

Ships

| Name | Laid down | Launched | Commissioned | Shipyard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist. | May 1886[17] | 23 July 1887[5] | 25 May 1888[5] | AG Vulcan, Stettin |

| Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist. | 22 September 1887[18] | 19 November 1889[18] | Germaniawerft, Kiel |

Service history

Both Irene and Prinzess Wilhelm saw extensive service with the German fleet in home waters early in their careers. Both ships frequently escorted Kaiser Wilhelm II's yacht, SMY Hohenzollern, on cruises throughout Europe; Irene accompanied the Kaiser on a voyage to the Mediterranean Sea in 1889–1890, and Prinzess Wilhelm escorted Hohenzollern for a number of cruises in northern European waters, including two visits to Norway. Prinzess Wilhelm also cruised in the Mediterranean in 1892, to represent Germany at celebrations marking the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's first voyage across the Atlantic. Both ships were refitted in the early 1890s.[19][20]

In 1894, Irene was deployed to East Asian waters; Prinzess Wilhelm joined her the following year.[8] Prinzess Wilhelm was one of three ships involved in the seizure of the naval base at the Jiaozhou Bay Leased Territory in November 1897, led by Admiral Otto von Diederichs.[21] Irene was in dock for engine maintenance at the time, and so she was not present during the operation.[22] As a result of the seizure, the Cruiser Division was reorganized as the East Asia Squadron.[23] Both ships were present in the Philippines in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Manila Bay between American and Spanish squadrons during the Spanish–American War in 1898.[24] Diederichs hoped to use the crisis as an opportunity to seize another naval base in the region, though this was unsuccessful.[25]

Prinzess Wilhelm returned to Germany in 1899 and was modernized in 1899–1903. Irene followed her sister back to Germany in 1901, but was not modernized. Both ships remained out of service until early 1914, when they were retired from front-line service and used for secondary duties. Irene was converted into a submarine tender. She served in this capacity until 1921, when she was sold for scrap and broken up the following year. Prinzess Wilhelm was reduced to a naval mine storage hulk in February 1914 and ultimately broken up for scrap in 1922.[8][26]

Notes

- ↑ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz Vol. 4, pp. 209–210.

- ↑ Nottelmann, p. 120.

- ↑ Nottelmann, pp. 120–121.

- ↑ Nottelmann, pp. 121–123.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz Vol. 4, p. 210.

- ↑ Nottelmann, p. 123.

- ↑ Gröner, p. 94.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Gröner, p. 95.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Gröner, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Nottelmann, p. 124.

- ↑ Nottelmann, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Lyon, p. 253.

- ↑ Brockhaus 1897, p. 308.

- ↑ Nottelmann, pp. 124, 129, 132.

- ↑ Nottelmann, pp. 129, 131.

- ↑ Nottelmann, p. 134.

- ↑ Nottelmann, p. 129.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz Vol. 7, p. 52.

- ↑ Sondhaus, pp. 179, 192.

- ↑ Nottelmann, pp. 129, 132.

- ↑ Gottschall, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Gottschall, p. 157.

- ↑ Gottschall, p. 165.

- ↑ Cooling, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Gottschall, p. 181.

- ↑ Nottelmann, pp. 132, 134.

References

- Brockhaus' Konversations-Lexikon, XVII, Brockhaus, Leipzig, Berlin, Wien, 1897, https://books.google.com/books?id=z6EfR2bk6eYC

- Cooling, Benjamin Franklin (2007). USS Olympia: Herald of Empire. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-126-6.

- Gottschall, Terrell D. (2003). By Order of the Kaiser, Otto von Diederichs and the Rise of the Imperial German Navy 1865–1902. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-309-1.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993) (in de). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart. 4. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0382-1.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993) (in de). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart. 7. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0267-1.

- Lyon, Hugh (1979). "Germany". in Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M.. Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5. https://archive.org/details/conwaysallworlds0000unse_l2e2.

- Nottelmann, Dirk (2023). Wright, Christopher C.. ed. "From "Wooden Walls" to "New-Testament Ships": The Development of the German Armored Cruiser 1854–1918, Part III: "Armor—Light Version"". Warship International LX (2): 118–156. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1997). Preparing for Weltpolitik: German Sea Power Before the Tirpitz Era. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-745-7.

Further reading

- Dodson, Aidan; Nottelmann, Dirk (2021). The Kaiser's Cruisers 1871–1918. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-68247-745-8.

Template:Irene class cruiser Template:German protected cruisers

|