Engineering:Omega (navigation system)

OMEGA was the first global-range radio navigation system, operated by the United States in cooperation with six partner nations. It was a hyperbolic navigation system, enabling ships and aircraft to determine their position by receiving very low frequency (VLF) radio signals in the range 10 to 14 kHz, transmitted by a global network of eight fixed terrestrial radio beacons, using a navigation receiver unit. It became operational around 1971 and was shut down in 1997 in favour of the Global Positioning System.

History

Previous systems

Taking a "fix" in any navigation system requires the determination of two measurements. Typically these are taken in relation to fixed objects like prominent landmarks or the known location of radio transmission towers. By measuring the angle to two such locations, the position of the navigator can be determined. Alternatively, one can measure the angle and distance to a single object, or the distance to two objects.

The introduction of radio systems during the 20th century dramatically increased the distances over which measurements could be taken. Such a system also demanded much greater accuracies in the measurements – an error of one degree in angle might be acceptable when taking a fix on a lighthouse a few miles away, but would be of limited use when used on a radio station 300 miles (480 km) away. A variety of methods were developed to take fixes with relatively small angle inaccuracies, but even these were generally useful only for short-range systems.

The same electronics that made basic radio systems work introduced the possibility of making very accurate time delay measurements, and thus highly accurate distance measurements. The problem was knowing when the transmission was initiated. With radar, this was simple, as the transmitter and receiver were usually at the same location. Measuring the delay between sending the signal and receiving the echo allowed accurate range measurement.

For other uses, air navigation for instance, the receiver would have to know the precise time the signal was transmitted. This was not generally possible using electronics of the day. Instead, two stations were synchronized by using one of the two transmitted signals as the trigger for the second signal after a fixed delay. By comparing the measured delay between the two signals, and comparing that with the known delay, the aircraft's position was revealed to lie along a curved line in space. By making two such measurements against widely separated stations, the resulting lines would overlap in two locations. These locations were normally far enough apart to allow conventional navigation systems, like dead reckoning, to eliminate the incorrect position solution.

The first of these hyperbolic navigation systems was the UK's Gee and Decca, followed by the US LORAN and LORAN-C systems. LORAN-C offered accurate navigation at distances over 1,000 kilometres (620 mi), and by locating "chains" of stations around the world, they offered moderately widespread coverage.

Atomic clocks

Key to the operation of the hyperbolic system was the use of one transmitter to broadcast the "master" signal, which was used by the "secondaries" as their trigger. This limited the maximum range over which the system could operate. For very short ranges, tens of kilometres, the trigger signal could be carried by wires. Over long distances, over-the-air signalling was more practical, but all such systems had range limits of one sort or another.

Very long-distance radio signalling is possible, using longwave techniques (low frequencies), which enables a planet-wide hyperbolic system. However, at those ranges, radio signals do not travel in straight lines, but reflect off various regions above the Earth known collectively as the ionosphere. At medium frequencies, this appears to "bend" or refract the signal beyond the horizon. At lower frequencies, VLF and ELF, the signal will reflect off the ionosphere and ground, allowing the signal to travel great distances in multiple "hops". However, it is very difficult to synchronize multiple stations using these signals, as they might be received multiple times from different directions at the end of different hops.

The problem of synchronizing very distant stations was solved with the introduction of the atomic clock in the 1950s, which became commercially available in portable form by the 1960s. Depending upon type, e.g. rubidium, caesium, hydrogen, the clocks had an accuracy on the order of 1 part in 1010 to better than 1 part in 1012 or a drift of about 1 second in 30 million years. This is more accurate than the timing system used by the master/secondary stations.

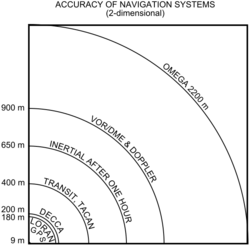

By this time the Loran-C and Decca Navigator systems were dominant in the medium-range roles, and short-range was well served by VOR and DME. The expense of the clocks, lack of need, and the limited accuracy of a long wave system eliminated the need for such a system for many roles.

However, the United States Navy had a distinct need for just such a system, as they were in the process of introducing the TRANSIT satellite navigation system. TRANSIT was designed to allow measurements of location at any point on the planet, with enough accuracy to act as a reference for an inertial navigation system (INS). Periodic fixes re-set the INS, which could then be used for navigation over longer periods of time and distances.

It was often believed that TRANSIT generated two possible locations for any given measurements one on either side of the orbit subtrack. Since the measurement is the Doppler shift of the carrier frequency, the rotation of the earth is sufficient to resolve the difference. The surface of the earth at the equator moves at a speed of 460 meters per second—or roughly 1,000 miles per hour.

OMEGA

Omega was approved for development in 1968 with eight transmitters and the ability to achieve a 4-mile (6.4 km) accuracy when fixing a position. Each Omega station transmitted a sequence of three very low frequency (VLF) signals (10.2 kHz, 13.6 kHz, 11.333... kHz in that order) plus a fourth frequency which was unique to each of the eight stations. The duration of each pulse (ranging from 0.9 to 1.2 seconds, with 0.2 second blank intervals between each pulse) differed in a fixed pattern, and repeated every ten seconds; the 10-second pattern was common to all 8 stations and synchronized with the carrier phase angle, which itself was synchronized with the local master atomic clock. The pulses within each 10-second group were identified by the first 8 letters of the alphabet within Omega publications of the time.

The envelope of the individual pulses could be used to establish a receiver's internal timing within the 10-second pattern. However, it was the phase of the received signals within each pulse that was used to determine the transit time from transmitter to receiver. Using hyperbolic geometry and radionavigation principles, a position fix with an accuracy on the order of 5–10 kilometres (3.1–6.2 mi) was realizable over the entire globe at any time of the day. Omega employed hyperbolic radionavigation techniques and the chain operated in the VLF portion of the spectrum between 10 and 14 kHz. Near the end of its service life of 26 years, Omega evolved into a system used primarily by the civil community. By receiving signals from three stations, an Omega receiver could locate a position to within 4 nautical miles (7.4 km) using the principle of phase comparison of signals.[1]

Omega stations used very extensive antennas to transmit at their very low frequencies (VLF). This is because wavelength is inversely proportional to frequency (wavelength in metres = 299,792,458 / frequency in Hz), and transmitter efficiency is severely degraded if the length of the antenna is shorter than 1/4 wavelength. They used grounded or insulated guyed masts with umbrella antennas, or wire-spans across both valleys and fjords. Some Omega antennas were the tallest constructions on the continent where they stood or still stand.

When six of the eight station chain became operational in 1971, day-to-day operations were managed by the United States Coast Guard in partnership with Argentina , Norway, Liberia, and France. The Japanese and Australian stations became operational several years later. Coast Guard personnel operated two US stations: one in LaMoure, North Dakota and the other in Kaneohe, Hawaii on the island of Oahu.

Due to the success of the Global Positioning System, the use of Omega declined during the 1990s, to a point where the cost of operating Omega could no longer be justified. Omega was shut down permanently on 30 September 1997. Several of the towers were then soon demolished.

Some of the stations, such as the LaMoure station, are now used for submarine communications.

Court case

In 1976 the Decca Navigator Company of London sued the United States government over patent infringements, claiming that the Omega system was based on a proposed earlier Decca system known as DELRAC, Decca Long Range Area Coverage,[2] that had been disclosed to the US in 1954. Decca cited original US documents showing the Omega system was originally referred to as DELRAC/Omega. Decca won the case and was awarded $44,000,000 in damages. Decca had previously sued the US government for alleged patent infringements over the LORAN C system in 1967. Decca also won that case, but as the LORAN C navigation system was judged to be a military one without commercial use, no damages were paid by the US.[1]

OMEGA stations

There were nine Omega stations in total; only eight operated at one time. Trinidad operated until 1976 and was replaced by Liberia:

Bratland Omega Transmitter

Bratland Omega Transmitter (station A – [ ⚑ ] 66°25′15″N 13°09′02″E / 66.420833°N 13.150555°E) situated near Aldra was the only European Omega transmitter. It used a very unusual antenna, which consisted of several wires strung over a fjord between two concrete anchors 3,500 metres (11,500 ft) apart, one at [ ⚑ ] 66°25′27″N 013°10′01″E / 66.42417°N 13.16694°E and the other at [ ⚑ ] 66°24′53″N 013°05′19″E / 66.41472°N 13.08861°E. One of the blocks was located on the Norway mainland, the other on Aldra island. The antenna was dismantled in 2002.

Trinidad Omega Transmitter

Trinidad Omega Transmitter (station B until 1976, replaced by station in Paynesville, Liberia) situated in Trinidad (at [ ⚑ ] 10°41′58″N 61°38′19″W / 10.69938°N 61.638708°W) used a wire span over a valley as its antenna. The site buildings are still there. On April 26, 1988 the building which housed the omega transmitters was destroyed by an explosion caused by a bush fire which ignited explosives. There were severe casualties and six persons died in the blast.

On April 26, 1988, a brush fire in the vicinity of Camp Omega, Chaguaramas, quickly spread to the nearby Camp Omega Arms and Ammunition Bunker resulting in the explosion. Four firefighters and two soldiers died while attempting to bring the situation under control. Several National Security Officers suffered injuries as a result of the explosion. This explosion was recorded on the Richter Scale and parts of the bunker were found hundreds of metres away from ground zero. The Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago dedicated April 26 each year as National Security Officers Day of Appreciation for the dead.

Paynesville Omega Transmitter

| Paynesville Omega Mast | |

|---|---|

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Type | Guyed grounded mast equipped with umbrella antenna |

| Location | Paynesville, Liberia |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] 06°18′20″N 010°39′44″W / 6.30556°N 10.66222°W |

| Completed | 1976 |

| Destroyed | May 10, 2011 |

| Height | 417 m (1,368.11 ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Main contractor | US Coast Guard |

Paynesville Omega Transmitter (station B – [ ⚑ ] 06°18′20″N 010°39′44″W / 6.30556°N 10.66222°W) was inaugurated in 1976 and used an umbrella antenna mounted on a 417-metre steel lattice, grounded guyed mast. It was the tallest structure ever built in Africa. The station was turned over to the Liberian government after the Omega Navigation System shutdown on 30 September 1997. Access to the tower was unrestricted, and it was possible to climb the abandoned mast until it was demolished on 10 May 2011. The area occupied by the transmitter will be used to build a modern market complex that will provide additional space for local merchants and reduce congestion at Paynesville's Red Light Market, Liberia's largest food market.[3]

Kaneohe Omega Transmitter

Kaneohe Omega Transmitter (station C – [ ⚑ ] 21°24′17″N 157°49′51″W / 21.404700°N 157.830822°W) was one of two stations operated by the USCG. It was inaugurated in 1943 as a VLF-transmitter for submarine communication. The antenna was a wire span over Haiku Valley. At the end of the 1960s it was converted to an OMEGA transmitter.

La Moure Omega Transmitter

| La Moure Omega Mast | |

|---|---|

| General information | |

| Status | Complete |

| Type | Mast radiator insulated against ground |

| Location | La Moure, North Dakota, United States |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] 46°21′57″N 098°20′08″W / 46.36583°N 98.33556°W |

| Height | 365.25 m (1,198.33 ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Main contractor | US Coast Guard |

La Moure Omega Transmitter (station D) situated near La Moure, North Dakota, USA at [ ⚑ ] 46°21′57″N 98°20′08″W / 46.365944°N 98.335617°W) was the other station operated by the USCG. It used a 365.25 metre tall guyed mast insulated from ground, as its antenna. After OMEGA was shut down, the station became NRTF LaMoure, a VLF submarine communications site.

Chabrier Omega Transmitter

| Chabrier Omega Mast | |

|---|---|

| General information | |

| Status | Destroyed |

| Type | Guyed grounded mast equipped with umbrella antenna |

| Location | Chabrier, Réunion |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] 20°58′27″S 55°17′24″E / 20.97417°S 55.29°E |

| Completed | 1976 |

| Destroyed | April 14th, 1999 |

| Height | 428 m (1,404.20 ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Main contractor | US Coast Guard |

Chabrier Omega Transmitter (station E) near Chabrier on Réunion island in the Indian Ocean at [ ⚑ ] 20°58′27″S 55°17′24″E / 20.97417°S 55.29°E used an umbrella antenna, installed on a 428-metre grounded guyed mast. The mast was demolished with explosives on 14 April 1999.

Trelew Omega Transmitter

Station F, Trelew, Argentina. Demolished in 1998.

Woodside Omega Transmitter

Station G, near Woodside, Victoria. Ceased Omega transmissions in 1997, became a submarine communications tower, and was demolished in 2015.

Omega Tower, Tsushima

| Omega Mast, Tsushima | |

|---|---|

Made based on National Land Image Information (Color Aerial Photographs), Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. | |

| General information | |

| Status | Destroyed |

| Type | Mast radiator insulated against ground |

| Location | Tsushima, Japan |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] 34°36′53″N 129°27′13″E / 34.61472°N 129.45361°E |

| Completed | 1973 |

| Destroyed | 1998 |

| Height | 455 m (1,492.78 ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Main contractor | US Coast Guard |

Shushi-Wan Omega Transmitter (station H) situated near Shushi-Wan on Tsushima Island at [ ⚑ ] 34°36′53″N 129°27′13″E / 34.61472°N 129.45361°E used as its antenna a 389-metre tall tubular steel mast, insulated against ground. This mast, which was built in 1973 and which was the tallest structure in Japan (and perhaps the tallest tubular steel mast ever built) was dismantled in 1998 by crane. On its former site, an approximately 8 metre-tall memorial consisting of the mast base (without the insulator) and a segment was built. On the site of the former helix building there is now a playground.

OMEGA test locations

In addition to the nine operational Omega towers, the tower at Forestport, NY was used for early testing of the system.

Forestport Tower

Cultural importance

The towers of some OMEGA-stations were the tallest structures in the country and sometimes even in the continent where they stood. In the German science-fiction novel "Der Komet" ( http://www.averdo.de/produkt/72105959/lutz-harald-der-komet/ ) a large comet, which threatens to hit the Earth, is defended against by a technology developed in Area 51 on the area of the abandoned OMEGA-transmission site Paynesville in Liberia, for which it delivers a required low-frequency electromagnetic field.

The season 2 finale of True Detective is called "Omega Station".

Episode 3 of the Netflix series Gamera Rebirth partially takes place at the Tsushima OMEGA-station.

See also

- Alpha, the Russian counterpart of the Omega Navigation System, still partially in use as of November 2017[update].

- Decca Navigator Decca had earlier proposed a system known as Delrac that Omega was subsequently based on.[1]

- LORAN, low frequency terrestrial radio navigation system, still in use (US and Canadian operations terminated 2010).

- CHAYKA, the Russian counterpart of LORAN

- SHORAN

- Oboe (navigation)

- G-H (navigation)

- GEE (navigation)

Bibliography

- Scott, R. E. 1969. Study and Evaluation of the Omega Navigation System for transoceanic navigation by civil aviation. FAARD-69-39.

- Asche, George P. USCG 1972. Omega system of global navigation. International Hydrographic Review 50 (1):87–99.

- Turner, Nicholas. 1973. Omega: a documented analysis. Australian Journal of International Affairs:291–305.

- Pierce, J.A. 1974. Omega: Facts, Hopes and Dreams. Cambridge Mass: Harvard Univ Div of Engineering and Applied Physics.

- Wilkes, Owen, Nils Petter Gleditsch, and Ingvar Botnen. 1987. Loran-C and Omega : a study of the military importance of radio navigation aids. Oslo; Oxford; New York: Norwegian University Press/Oxford University Press. ISBN 82-00-07703-9

- Gibbs, Graham. 1997. Teaming a product and a global market: a Canadian Marconi company success story. Reston, VA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. ISBN 1-56347-225-2; ISBN 978-1-56347-225-1 [A case study of the commercial development of the Omega Navigation System]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Omega". http://www.jproc.ca/hyperbolic/omega.html.

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1956/1956%20-%200541.html.

- ↑ "Tallest Structure in Africa Demolished to Make Way for Modern Market Complex". Government of the Republic of Liberia. May 10, 2011. http://www.emansion.gov.lr/press.php?news_id=1889.

External links

- The Omega Navigation System (1969) – USN Training Film

- オメガ鉄塔建設工事の記録("Record of the Tsushima Omega tower construction"), Japanese, 1974

- OMEGA By Jerry Proc VE3FAB

- LF Utility Stations 10-100 kHz (compiled by ZL4ALI)

- Pictures of former OMEGA-Station La Moure

- Views of all eight Omega stations

|