Engineering:USFC Grampus

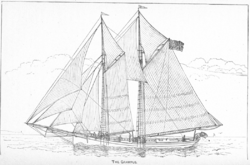

USFC Grampus off Massachusetts in 1902.

Script error: The function "infobox_ship_career" does not exist. Script error: The function "infobox_ship_career" does not exist. | |

| General characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Type: | Fisheries research ship |

| Tonnage: | 83.30 net register tons |

| Displacement: | 484 tons |

| Length: | |

| Beam: | 22 ft 9 in (6.9 m) |

| Draft: | 11 ft 6 in (3.5 m) (maximum)[1] |

| Depth: | 11 ft 1 in (3.4 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 10 ft (3.0 m)[1] |

| Propulsion: | Sailing ship |

| Sail plan: | Two-masted schooner rig |

| Boats & landing craft carried: | |

| Crew: | 8[2] plus other embarked personnel |

USFC Grampus was a fisheries research ship in commission in the fleet of the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries, usually called the United States Fish Commission, from 1886 to 1903 and then as USFS Grampus in the fleet of its successor, the United States Bureau of Fisheries, until 1917. She was a schooner of revolutionary design in terms of speed and safety and influenced the construction of later commercial fishing schooners.[3]

Grampus′s home ports were Woods Hole and Gloucester, Massachusetts . During her 31-year career, Grampus made significant contributions to the understanding of the mackerel fishery off the United States East Coast , Canada , and the British colony of Newfoundland. She also investigated the tilefish population, conducted fishery investigations in the Gulf of Mexico, and contributed to fish culture work in New England to propagate the mackerel, cod, and lobster.

Design

Fish Commission requirements

Fishery scientists of the late 19th century believed that successful spawning was the most significant factor in the productivity of fisheries, and the Fish Commission had placed the fisheries research ship USFC Fish Hawk in service in 1880 to serve as a floating fish hatchery that could move up and down the coast in accordance with the timing of American shad runs.[4] Grampus was constructed to fill a need the Fish Commission perceived for a ship with a well in which marine fishes could be kept alive and transported from the fishing grounds to fish hatcheries on the coast of the United States , where fisheries researchers could collect their eggs for use in the hatcheries and further ensure productive fisheries. Grampus also was to bring back fish for biological study of the fish themselves.[3]

Grampus also needed to be seaworthy and fast, so as to be able to collect fish from European waters and bring back to the United States fish such as sole, turbot, plaice, and brill – which were important to the European commercial fishing industry but did not occur naturally in the waters off North America – so that they could be introduced into waters off the United States. Grampus also was to demonstrate the method of beam trawling used by European fishermen in the North Sea but not in the United States at the time to catch groundfish, and to spur the use of beam trawling by American commercial fishermen in the hope of increasing the monetary value of the American catch and to provide additional employment for men aboard American fishing vessels. The Fish Commission believed that groundfish species native to the waters off North America could be profitably fished even though they differed from the species found in European waters, and Grampus was to use beam trawling to test this idea.[3]

The Fish Commission wanted to develop a comprehensive understanding of the migration of food fishes in the spring and autumn as they travelled to and from their summer feeding grounds, and chose to construct Grampus as a sailing ship because it wanted her to be able to remain at sea for weeks or months at a time to follow the migration continuously and investigate it completely without having to come into port for coal, as a steamer would. Grampus also had to be seaworthy enough to remain on duty and not lose contact with the migrating fish during bad weather. Finally, Grampus had to be designed and equipped to capture fish that did not swim near the surface in order to investigate fisheries completely, and she also needed to be able to capture and investigate minute life such as plankton, which supported the food fish population.[3]

Grampus needed a windlass in order to work her gear, and the Fish Commission opted for a steam windlass. United States Navy Lieutenant Commander Zera Luther Tanner, an influential inventor and oceanographer of the era, commanding officer of the Fish Commission's fisheries research ship USFC Albatross, and previously the first commanding officer of Fish Hawk, received the task of determining what type of steam apparatus Grampus should carry. He chose a steam windlass with engines of 35 horsepower (26.1 kW). Operating the windlass required the installation of a boiler, steam pump, iron water tanks, and associated piping.[3]

Speed and safety

In addition to meeting the Fish Commission's research and fish culture requirements, Grampus's design also reflected ideas for improvement in the design of the then-conventional New England commercial fishing schooners so as to improve both speed and safety.[3] In the mid-1880s, these schooners tended to be wide, shallow, and sharp so as to allow the greatest possible speed by reducing drag through the water and allowing the ship to carry a considerable amount of sail. In order to keep the hulls shallow, the schooners were "very wide aft, with a heavy, clumsy stern and fat counters, the run being hollowed out excessively so as to produce in the after section a series of very abrupt horizontal curves."[3] The two masts came to nearly the same height above the waterline, and the schooners carried a large jib extending from the bowsprit end to the foremast.[3]

This traditional schooner design had a number of drawbacks. The shallow hull did not, in fact, contribute significantly to speed, and the wide stern design actually hindered fast sailing. The ships' shallowness of hull gave them a high center of gravity that made them prone to capsizing and sinking in heavy seas, often with significant or total loss of life among their crews. The foremast rising to the same height as the mainmast often meant either that the jib when raised to the top of the foremast caused an inefficient, asymmetrical sail pattern, or that the upper parts of the foremast were left unused; having a foremast that was taller than necessary added extra expense to the cost of the ship's construction and also meant that she had an unnecessary amount of weight aloft, making her less stable and more prone to dangerous rolling and capsizing. The large jib also created problems, moving the sails' center of effort too far forward when the schooner shortened sail and the mainsail was reefed, making the ship harder to handle. Moreover, handling the large jib required crew members to work on the bowsprit in bad weather, a dangerous practice that resulted in men being swept overboard and drowned.[3]

To address these issues, Grampus, although similar in design to the traditional New England schooner, also differed in significant ways.[3] She had a hull 18 to 24 inches (0.5 to 0.6 m)[1] deeper than traditional schooners of similar length, giving her greater stability, and her beam was 6 to 10 inches (0.2 to 0.3 m) less than that of a traditional schooner.[1] She had a straight stem, rather than a raking one, and her stern was narrower and more raked, with her after portion approximating a V-shape, all changes which increased her hull length at the waterline. Her foremast was considerably shorter than her mainmast, and her rigging was designed so that she could carry a double-headed rig forward that allowed her to use a smaller jib that could be furled upon the approach of heavy weather and a fore staysail running from the foremast to near her stem. The result was a ship able to achieve higher sailing speeds, able to make more efficient use of her sails, with no need for crew members to work on her bowsprit during bad weather, and less likely to capsize in heavy seas.[3]

Ideas for the changes in schooner design to make these improvements had been discussed as early as 1882, but Grampus's design was the first to put them into practice. A model of Grampus went on display in 1885 at the American Fish Bureau in Gloucester, Massachusetts , and attracted much attention. Her design influenced that of many future commercial fishing schooners.[3][1] The U.S. Fish Commission′s Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1901 said that "her superiority in safety, speed, and other desirable qualities has been fully established"[1] and "[a]fter twelve years' service [i.e., through at least 1898] the Grampus is unexcelled in speed by fishing vessels or pilot boats[1] Referring to shipbuilding in New England, the report added, "Nearly all of the fishing vessels recently built are deeper than formerly, and embody other features that characterize the Grampus. The spirit of improvement has received such an impetus that the best skill of the most eminent naval architects has of late been devoted to designing fishing vessels."[1]

Other characteristics

Grampus was of wooden construction, built largely of white oak with some white pine deck planking.[5] She was 90 feet (27.4 m) in length overall.[6] Her fish well was pyramidal in shape, 16 feet (4.9 m) long and about 8 feet (2.4 m) wide at the bottom and 4 feet (1.2 m) long and about 2.5 feet (0.8 m) wide at the top, and it had 204 2.5-inch (6.4 cm) holes in its bottom planks to allow seawater to circulate through it.[7] A laboratory was situated just aft of the well;[8] it contained closet space and shelving to hold specimens in jars of alcohol, medicines, the ship′s library of over 100 volumes,[9] fishing gear, and signal gun equipment.[8] The ship was equipped to store specimens on ice.[10]

For fishing, Grampus was rigged for trawling,[11] hand-line fishing,[12] gillnetting,[13] seining,[14] dredging,[15] and squid jigging.[16] She had equipment for capturing the eggs of pelagic fishes and keeping the eggs alive or hatching them once they were aboard.[17] She also was equipped to harpoon swordfish and porpoises, with a pulpit for this purpose mounted on her jib boom end.[16] She carried guns with which her personnel could shoot birds and seals so that their carcasses could be collected for study. To collect environmental information, she carried sounding equipment and deep-sea thermometers.[18]

Grampus′s sail suit consisted of a foresail, a fore staysail, a riding sail, a mainsail, a jib, a flying jib, a fore gaff topsail, a main gaff topsail, a main topmast staysail, and a balloon jib.[19] She carried five boats: a 33-foot (10.1 m) carvel-built seiner rigged as a schooner;[20] a 17-foot (5.2 m) carvel-built open dinghy rigged as a sloop;[21] and three 19-foot-4-inch (5.9 m) dories.[22] She also carried three 13-foot (4.0 m) "live-cars," dory-like craft covered with heavy netting through which seawater could circulate freely. They were intended to keep fish alive after crew members manning the dories hauled in trawl lines; the men in the dories could dump the live fish into a live-car alongside each dory as they reeled in the lines.[23]

Construction

By the spring of 1885, the United States Congress had appropriated $14,000 (USD) for the design and constriction of Grampus and design of the ship began.[3] Under the supervision of U.S. Fish Commission Captain J. W. Collins,[24] Grampus's hull was constructed at Noank, Connecticut, by Robert Palmer & Sons, which launched her on 23 March 1886. Her sails, rigging, blocks, and ground tackle came from E. L. Rowe & Son, of Gloucester; her boats from Higgins & Gifford, of Gloucester; her steam windlass from the American Ship Windlass Company of Providence, Rhode Island; and the boiler for the windlass from M. V. B. Darling of Providence. The rest of her equipment came mainly from Bliss Brothers and H. M. Greenough of Boston, Massachusetts.[3]

Service history

U.S. Fish Commission

1880s

The Fish Commission commissioned Grampus on 5 June 1886 under the command of Captain J. W. Collins.[24] She departed Noank that day for Woods Hole, Massachusetts ,[3][25][26] which was to be her home port. After a stopover at Woods Hole from 6 to 8 June 1886,[26] she departed for Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she arrived on 9 June 1886 and took aboard her boats and fishing gear – all of which had been manufactured at Gloucester – and made alterations to her sails.[26] That work completed, she sailed on 14 June 1886 to Boston, Massachusetts, where she took aboard her marine chronometer and "other instruments and apparatus."[26] She spent 16-22 June 1886 at Gloucester, then sailed to Woods Hole, arriving there on 23 June 1886 to begin preparations for her first scientific cruise.[26]

That cruise began on 21 August 1886, when Grampus departed Woods Hole[26] to determine the status of the tilefish off Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts.[25][27] Discovered in 1879,[28] first collected scientifically at sea by the Fish Commission steamer missing name in 1880, and abundant enough in 1880 and 1881 to suggest the development of a new fishery, the tilefish had experienced a massive die-off in 1882, with many millions of dead fish found between Nantucket, Massachusetts, and Cape May, New Jersey.[27][29] After a week on the fishing grounds without finding a single tilefish[30] – prompting Collins to propose that the species was at least locally extinct[30] – Grampus set course for Woods Hole, arriving there on 24 August 1886.[26][30]

The voyage doubled as a shakedown cruise, and it demonstrated that the steam windlass and its engines and boiler were too heavy for Grampus, adding so much weight forward as to make her difficult to manage in a seaway.[3][30] She therefore arrived on 2 September 1886 at Gloucester,[30] where the windlass was replaced by a new wooden one manufactured for her there.[31] With her new windlass installed, she departed Gloucester on 22 September for a cruise to La Have Bank and Roseway Bank in the North Atlantic Ocean south of Nova Scotia, Canada , and Seal Island Ground in the Gulf of Maine to collect live cod and halibut for return to Woods Hole for study and propagation, i.e., fish culture work.[25][32] During the cruise, Grampus received a "perfect specimen" of the squid Sthenoteuthis megaptera – only the second perfect specimen of the species ever collected and the first in United States, preceded only by one collected in Canada – from the Gloucester-based schooner Mabel Leighton on 26 September 1886.[33] However, she had little success in her primary objective, finding that cod and halibut caught in deep water died soon after being placed in her well, apparently because of the rapid change in pressure and temperature as they were hauled to the surface.[34] Her attempts to catch halibut in shallow water met with no success.[35] She returned to Woods Hole on 12 October 1886[25][36] and offloaded fish she had collected as well as seabirds her personnel had shot for study.[37]

Grampus made a single-day voyage to visit the mackerel-fishing fleet in the western part of Vineyard Sound off Gay Head, Massachusetts,[25] then was engaged until March 1887 in voyages to collect spawning cod and investigate the fisheries in the Gulf of Maine, Massachusetts Bay, and Vineyard Sound, finding some success in bringing cod back alive in her well to Woods Hole, although over 95 percent of fish still died in the well.[25][38] On 3 April 1887, she departed Woods Hole to conduct a cruise along the United States East Coast from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.[39][40] The reasons for the behavior of mackerel during their annual spring appearance off the coasts of the United States and Canada were poorly understood when Grampus entered service,[41] and the cruise began a lengthy involvement for her in examining mackerel behavior as she studied schools of mackerel as they moved toward the coast early in the fishing season and how factors such as temperature and food sources influenced their subsequent movements.[39] She completed this work for the season on 31 May 1887,[39] then returned to Woods Hole on 4 June 1887.[42] On 3 July 1887 she sailed north to investigate reports of mackerel in the North Atlantic Ocean northeast of Newfoundland and collect birds, bird eggs, and remains of the great auk,[42] which had become extinct in the mid-19th century. She proceeded along the coast of Nova Scotia as far as Canso, into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, north to the Magdalen Islands, to St. John's, Newfoundland, and then along the eastern coast of Newfoundland, finding no sign of mackerel but collecting many specimens of flora and fauna as well as a significant number of great auk bones.[43] She returned to Woods Hole on 1 September 1887.[44] She spent the winter of 1887–1888 making cruises off Massachusetts to collect brood cod.[45]

From April through July 1888, Grampus returned to the mackerel fishing grounds between Cape Cod and Cape Hatteras, collecting living eggs and embryos for fish-culture work and experimenting successfully with returning living mackerel to port in her well.[43] In May 1888, she also studied menhaden reproduction in the lower Chesapeake Bay.[43] Late in the 1888 fishing season, she investigated the mackerel fishery between Nantucket and Virginia,[46] and she collected brood cod during October and the first half of November 1888.[47] This effort came to an end on 15 November 1888, when she ran aground during a gale on Bass Rip[48] ( [ ⚑ ] 41°17′00″N 69°53′58″W / 41.2834554°N 69.8994561°W), a shoal in the North Atlantic 2.5 nautical miles (4.6 km; 2.9 mi) east of Nantucket Island off the coast of Massachusetts.[49] With the weather giving signs of deteriorating further, her crew abandoned ship.[48] Unmanned, she floated free and was adrift for several days before she was recovered and taken to Woods Hole.[48] She underwent repairs at Gloucester.[48]

Grampus departed Woods Hole on 14 January 1889, arrived at Key West, Florida, on 27 January 1889, and began operations in the Gulf of Mexico to study the red snapper fishery on the continental shelf off the west coast of Florida in waters 90 to 300 feet (27 to 91 m) deep, continuing these operations until 27 March 1889 and battling a great deal of stormy weather to conduct her investigation.[50] From late July through early September 1889 she conducted research in waters south of Massachusetts and Rhode Island and between the eastern end of Nantucket Island and Block Island, taking water temperature readings to a depth of as much as 3,000 feet (910 m) and making meteorological observations at stations along a series of parallel lines extending as far as 130 nautical miles (240 km; 150 mi) from the coast.[51][52] Her work began a multiyear effort to record temperatures in vertical water columns and associated weather above those columns to discern the interaction between the Gulf Stream and colder waters and the possible effect of that interaction on the behavior of various food fishes, especially the mackerel.[51][52] In September 1889 she began collecting cod eggs off Massachusetts for the Bureau of Fisheries station at Gloucester, continuing that work until the following spring.[53]

1890s

Grampus completed her cod collection duties off Massachusetts for the season in May 1890.[53] From 3 July to 25 August 1890, she resumed the work of recording water temperatures and weather off southern New England she had begun in the summer of 1889, this time joined in the effort by the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey survey steamer missing name and observers stationed aboard the Nantucket South Shoals Lightship.[51][52] Grampus again collected brood cod over the winter of 1890–1891.[54] From 5 May to 18 June 1891, she again investigated the mackerel fishery off the U.S. East Coast between Massachusetts and Delaware, continuing the inquiry into how weather and water temperature influenced the seasonal movements of mackerel.[55] Following that, she operated off southern New England for the third consecutive summer, from 30 June to 1 September 1891, to continue the study of vertical water columns and weather begun in 1889, this time operating only with the support of personnel embarked on the lightship.[56][57] On 5 September 1891, Grampus was on a voyage from Hyannis, Massachusetts, to Woods Hole with U.S. Commissioner of Fisheries Marshall McDonald and his wife and daughter, Assistant U.S. Fish Commissioner J. W. Collins (her former captain), and two female guests aboard when she ran aground on L'Hommidieu Shoal in Vineyard Sound during a southeasterly storm. McDonald, Collins, McDonald's family members, and the other two women made it safely to Falmouth, Massachusetts, in a dory, and Grampus later was refloated and returned to service.[58]

In late June 1892, Grampus began an assignment in the lower Chesapeake Bay and the waters of the North Atlantic outside its mouth to ascertain the abundance of fishes in the region;[56] she completed this work on 20 July 1892.[59] Before the end of July, with Commissioner McDonald aboard, she began an investigation under his personal direction of the waters off southern New England to see if the tilefish had returned to those waters; the water-column studies of 1889 through 1891 in which she had participated demonstrated a return of warmer water to the depths the tilefish inhabited, and during several voyages in waters between Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts, and Cape Henlopen, Delaware, she collected eight tilefish during the remainder of the summer, the first found there since the tremendous tilefish die-off of 1882.[60] This finding supported a hypothesis that an influx of cold water had killed the tilefish in 1882 and that the species would reestablish itself as warmer water spread back into the area.[60] She spent the autumn of 1892 and winter of 1892–1893 in New England waters on fish egg collection duties and in largely unsuccessful attempts to capture live cod.[61]

In the spring of 1893, the Fish Commission tasked Grampus to evaluate the success of a five-year ban the United States Congress had passed in 1886 on the taking of mackerel prior to 1 June of each year – a prohibition which had expired after the 1892 season – by following the commercial fishing fleet throughout the entire 1893 spring mackerel season to see what effect the five-year ban had had on the mackerel population off the U.S. East Coast.[62] During her cruise, she was to obtain specimens of mackerel, record physical conditions continually, and use towed nets to gather organisms that mackerel feed on.[63] Departing Woods Hole on 10 April 1893, she arrived at Lewes, Delaware, on 21 April after a stormy passage and met the mackerel fleet there.[63] The mackerel catch and weather both were poor, and by mid-May 1893 the fleet had moved north, following the mackerel in their annual migration.[63] After calling at Woods Hole for supplies, Grampus departed on 23 May 1893 to follow the fleet to the waters off Nova Scotia.[63] There the mackerel catch improved significantly after 1 June 1893, and Grampus returned to Woods Hole in late June 1893 with a good collection of specimens and complete set of observations.[63] She again searched for tilefish in July and August 1893 with Commissioner McDonald aboard.[64]

Grampus again shadowed the mackerel fleet in the spring of 1894, departing Gloucester on 7 April. She was bound from Gloucester to Woods Hole before proceeding to Lewes when a serious nor'easter struck, raising significant concerns for her safety.[65] She survived, however, and operated from Lewes from 20 April to 10 May, hampered as she had been a year earlier by heavy weather.[66] She followed the fleet north to fishing grounds off the coast of New York, and then across Georges Bank to Cape Sable Island and Nova Scotia.[67] She then continued to follow schools of mackerel into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence as far north as Cape North.[67] Completing this work she departed for Gloucester on 13 June, arriving there on 25 June.[67] During the last half of July and first half of August 1894, she cruised the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to examine the mackerel fishery there.[41] After egg collection duty in the autumn of 1894 and winter of 1894–1895, she spent another spring in 1895 following mackerel schools, beginning her cruise on 12 April, operating from Lewes until 10 May, then following the mackerel to waters off New York, across Georges Bank and Browns Bank to Nova Scotia, to Cape North on Cape Breton Island, and then briefly in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence before returning to Gloucester, where she arrived on 30 June 1895.[41] From 8 August to late September 1895, she conducted the first investigation of mackerel abundance and behavior and associated environmental factors in the waters off northern New England, operating between the Bay of Fundy and Block Island.[68]

Grampus resumed the collection of information on the mackerel in the spring of 1896, leaving Gloucester on 11 April, arriving at Lewes on 16 April, leaving Lewes on 8 May, and working her way north along the coast of New Jersey and east along the coast of Long Island and Block Island before arriving at Woods Hole on 14 May.[68] In May and early June 1896 Grampus collected mackerel eggs in the Vineyard Sound area and off Chatham, Massachusetts,[69], and in the latter part of June she was stationed at Small Point, Maine, to collect mackerel eggs in support of the Fish Commission steamer Fish Hawk at Casco Bay.[70] The lobster fishery had been in decline for a number of years,[71] so in July Grampus moved to Rockland, Maine, to support Fish Hawk, which had moved to Boothbay Harbor, in collecting lobster eggs, concluding this work on 3 August 1896 and returning to Gloucester.[72] During the autumn of 1896 and over the winter of 1896–1897 she collected cod eggs.[73] From May to June 1897, she collected lobsters along the coast of Maine from Portland to Rockland and transported them to the Fish Commission station at Gloucester with no difficulty; after the lobsters had been stripped of their eggs at Gloucester, she then released them along with lobster fry along the coast of Maine during her return voyage.[74] She collected brood cod off Massachuetts in October and November 1897 and lobsters along the entire coast of Maine between April and July 1898,[75] and released lobster fry along the coast of Maine.[76] In "one of the most noteworthy investigations of the [Fish] Commission" and "one of the leading features of the fishing industry" during fiscal year 1899 (which ran from 1 July 1898 to 30 June 1899), she conducted a systematic study of tilefish populations on the edge of the continental shelf off southern New England and Long Island during three cruises between August and October 1898 and found tilefish in abundance, bringing back the hope the Fish Commission last held in 1880–1881 that a commercial tilefish fishery would develop.[77] In October and November 1898 she collected brood cod along the coast of Massachusetts for the Fish Commission station at Woods Hole.[78] During the summer of 1899 she made three cruises to the Gulf Stream to study the state of the tilefish fishery.[79] She collected brood cod off Massachusetts for the Woods Hole station in October and November 1899.[80]

1900s

Between April and the beginning of July 1900, Grampus collected egg-bearing lobsters along the coast of Maine between Portland and Eastport with the assistance of a steam smack.[81] During the summer of 1900 she made a successful cruise to study the tilefish fishery.[82] In October 1900 she collected brood cod for the Woods Hole station, fishing as in years past in the vicinity of the Nantucket Shoals; she had caught 4,000 to 6,000 cod every autumn since 1897.[83] In the spring of 1901, although delayed by stormy weather that persisted throughout April and early May, she collected egg-bearing lobsters for the Fish Commission′s Gloucester station during operations along the coast of Maine from Portland to Rockland, again assisted by a steam smack, and released lobster fry along the coast of Maine during her return trip from Gloucester.[84] After a chase of several days and nights off the coast of Maine, she captured two harbor seal pups which went on display in a large pool as part of the Fish Commission′s exhibit at the Pan-American Exposition of 1901 in Buffalo, New York, but they both died during the exposition′s final week.[85]

On 28 July 1901, Grampus embarked a small party from the Fish Commission′s Woods Hole station and left Woods Hole bound for fishing grounds 70.5 nautical miles (131 km; 81 mi) south and 0.5 nautical miles (0.9 km; 0.6 mi) east of Nomans Land to collect tilefish.[86] Reaching the fishing grounds that night, she began trawling on the morning of 29 July in the vicinity of [ ⚑ ] 40°06′N 070°24′W / 40.1°N 70.4°W at a depth of 390 to 420 feet (120 to 130 m) and two hours later brought 62 tilefish weighing a combined 700 pounds (320 kg) to the surface.[86] She returned with them to Woods Hole on 30 July, and the Fish Commission shipped her catch to dealers in Boston, Gloucester, and New York City who had agreed to cooperate with the Commission in its goal of establishing a commercial tilefish fishery.[86] She collected brood cod off Massachusetts for the Woods Hole station from 2 October to 3 November 1901.[87]

From 18 April to 18 July 1902, Grampus collected egg-bearing lobsters along the coast of Maine between Wood Island and Eastport for the Gloucester station, assisted as in previous years by a steam smack,[88] and during the remainder of the summer assisted in the work of the Woods Hole station.[89] One of her most significant achievements that summer was in response to a request by fish dealers and curers for more tilefish with which to spur the development of a commercial tilefish fishery; departing Woods Hole on 30 July 1902, she proceeded to fishing grounds 76 nautical miles (141 km; 87 mi) southeast by south of Nomans Land and on 31 July in five trawl sets at [ ⚑ ] 40°10′45″N 070°20′30″W / 40.17917°N 70.34167°W at a depth of 390 feet (120 m) caught 474 tilefish ranging in size from 3 to 40 pounds (1.4 to 18.1 kg) and totaling 7,000 to 8,000 pounds (3,200 to 3,600 kg).[90] It was the largest catch of tilefish ever made at the time,[91] and after she landed them at Woods Hole and they were shipped to fish dealers, the dealers found success in selling them.[91] In the autumn of 1902 she collected brood cod at Nantucket Shoals for the Gloucester station.[89] In the spring of 1903 she collected egg-bearing lobsters off Maine.[89]

U.S. Bureau of Fisheries

1900s

By an Act of Congress of 14 February 1903, the U.S. Fish Commission became part of the newly created United States Department of Commerce and Labor and was reorganized as the United States Bureau of Fisheries, with both the transfer and the name change effective on 1 July 1903.[92] As USFS Grampus, Grampus became part of the Bureau of Fisheries fleet.

In the summer of 1904, Grampus collected egg-bearing lobsters in Maine, and in October and November 1904 she collected brood cod off Massachusetts. Laid up over the winter of 1904–1905, she reentered service on 1 April 1905 for another stint collecting egg-bearing lobsters.[93] By mid-1905, the Bureau of Fisheries was reporting to the United States Secretary of Commerce and Labor that after 19 years of active service, Grampus would soon be in need of major repairs and reconstruction to keep her seaworthy, and that the Bureau viewed it as highly desirable that auxiliary motor power be installed aboard her to supplement her sails.[93] In the summer of 1905, her usual duties of lobster collection were interrupted when she was tasked to transport Bureau of Fisheries representatives to Newfoundland to examine herring fisheries in its waters at the request of New England fishing interests and determine the effect on American herring-fishing vessels of fishing regulations recently passed by the colony's government.[94] Grampus took the opportunity to make observations related to mackerel in the region and to study local fishing and fish preservation practices in Newfoundland during the voyage.[95] The Bureau representatives found nothing irregular and that Newfoundland was enforcing fishing regulations in accordance with the Treaty of 1818,[95] but in mid-1906 the Bureau again reported to the Secretary of Commerce and Labor that the voyage demonstrated both the need for repairs to and reconstruction of Grampus and the installation of motor power aboard her if she was to remain an effective part of the Bureau′s fleet.[96]

Grampus completed her annual lobster collection duties off Maine in late September 1906, then was dismantled at Gloucester in anticipation of undergoing the major repairs and reconstruction advocated by the Bureau.[97] After the U.S. Congress appropriated US$7,500 for her repairs,[98] she was sent to Boothbay Harbor, Maine, for reconstruction in June 1907.[97] After the completion of her repairs and reconstruction, Grampus – now referred to as an "auxiliary schooner" by the Bureau of Fisheries – began a cruise of several weeks in July 1908 to study animal life in the Gulf Stream off southern New England, collecting creatures from both deep and shallow water and taking soundings and temperature readings.[99]

In the spring of 1909 at the request of the Board of Trade and Master Mariners' Association of Gloucester, the Bureau agreed to investigate mackerel schools believed to congregate in waters remote to those visited annually by the seining fleet,[100] testing a belief among some fishermen that the replacement of older hook-and-line fishing methods by seining and gillneting over the previous 20 years had dispersed mackerel schools and led to a decline in the productivity of the mackerel fishery.[101] On 7 April 1909, Grampus departed from Gloucester to conduct the study.[102] She joined the seining fleet at Lewes, Delaware on 2 May 1909 and began her mackerel study, making her first experiments that day at [ ⚑ ] 38°00′N 78°21′W / 38°N 78.35°W.[102] Her cruise made experimental use of gillnets and lines to catch mackerel and tow nets to detect minute crustaceans mackerel feed on.[100] Focusing initially on the southern fishing grounds from Cape Henry, Virginia, north to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, where mackerel runs first began each spring, and hampered by stormy weather, she remained behind after the fishing fleet moved north to see if she could detect any mackerel remaining behind, as might be the case if newer fishing methods were dispersing them.[100][102] No mackerel remained behind, however, and Grampus worked her way north to follow the fish, working her way across Georges Bank and Browns Bank and making port calls in Nova Scotia at Sandy Point from 5 to 8 August 1909, at Halifax, from which she departed on 12 August, and North Sydney, from which she sailed on 15 August.[102] For the rest of August and during September she worked in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and along the south coast of Newfoundland; she then departed the region on 10 October 1909[103] bound for Gloucester, where she arrived on 16 October 1909.[102] Her cruise failed to discover where the southern population of mackerel went after it disappeared from the fishing grounds off Long Island each year or where the northern population went after its annual departure from the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, but Grampus did discover that weather and the presence of schools of predatory bonito had a much larger impact on the abundance of mackerel on the fishing grounds than previously suspected.[104]

1910s

Inactive over the winter of 1909–1910, Grampus began her annual lobster collection duties in April 1910.[103] She conducted her routine fish-culture work during fiscal year 1911 (1 July 1910-30 June 1911)[105] and fiscal year 1912 (1 July 1911–30 June 1912).[106] In July and August 1912, she explored the oceanography of the Gulf of Maine to determine the physical and biological conditions governing the distribution of fish food and young fishes.[107] In the summer of 1913 she studied the oceanography of waters from the Gulf of Maine to the Virginia Capes, discovering previously unknown scallop beds.[108] In late 1913 and early 1914, she provided living quarters for personnel collecting pollock spawn.[109] In the summer of 1914, she conducted oceanographic work from the Gulf of Maine to Nantucket, then was laid up over the winter of 1914–1915.[110] She resumed her oceanographic work in the Gulf of Maine on 4 May 1915,[110] continuing it until 27 October 1915.[111] She was laid up for the winter of 1915–1916.[111]

From 18 July 1916 to 24 April 1917, Grampus conducted her final scientific work for the Bureau of fisheries, with oceanographic and other investigations off the U.S. East Coast and fishery investigations in the Gulf of Mexico.[112] Early in the winter of 1916–1917, she investigated banks near Cape Fear, North Carolina, whose productivity were unknown to fishermen; she was hampered by storms and was able to study only two of the potential fishing grounds, but found one to be a good site to fish for sea bass or blackfish and the other productive for drifting fishing vessels.[113] Later in the winter she moved on to the Gulf of Mexico, where she overcame interruptions by fog and storms to study the shrimp fishery there. In her otter trawl, she found shrimp in abundance off Mobile Bay on the coast of Alabama, on the southeast side of Ship Island on the coast of Mississippi, and southeast of Barataria Pass on the coast of Louisiana.[113] Wrapping up her Gulf of Mexico work, she reached Washington, D.C., in April 1917, then proceeded to Gloucester.[112]

Disposal

After Grampus returned to Gloucester in 1917, major defects were found in her hull that would require considerable expense to repair.[112] Deeming her of obsolete design,[112] no longer suited to its needs,[112] and not worth repairing, the Bureau of Fisheries condemned and sold her during fiscal year 1918 (1 July 1917–30 June 1918).[114]

References

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Commissioner's Report 1901, p. 324.

- ↑ United States Civil Service Commission, Official register of the United States Containing a List of Officers and Employees in the Civil, Military, and Naval Service Together With a List of Vessels Belonging to the United States July 1, 1905, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1905, p. 1087.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 NOAA History: Report On The Construction And Equipment Of The Schooner Grampus

- ↑ NOAA History: R/V Fish Hawk 1880-1926

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, pp. 444–445.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 442.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 446.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 456–457.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 456.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 456.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, pp. 481–482.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, pp. 480–481.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, pp. 483–484.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 484.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 486.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 485.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 479.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 474.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 462.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, pp. 465–466.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 468.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 469.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 470.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Commissioner's Report 1901, p. 323.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Commissioner′s Report 1886, p. xlvii

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 26.6 Commissioner's Report 1886, p. 701.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Commissioner's Report 1886, p. 702.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1897, p. cxxi.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1893, p. 34.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 Commissioner's Report 1886, p. 703.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1886, p. 704.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report, 1886, p. 705.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1886, p. 706.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1886, p. 709.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1886, pp. 711–712.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1886, p. 712.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1886, p. 708.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1886, p. 716–717.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Commissioner's Report 1887, p. liv.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 494.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Commissioner's Report 1895, p. 80.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 495.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Commissioner's Report 1887, p. lv.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 509.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1887, pp. 551–555.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1888, p. lxxxiv.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1888, p. xxiv.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 Commissioner's Report 1888, pp. cxx-cxxi.

- ↑ MA Home Town Locator: Bass Rip in Nantucket County MA

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1888, pp. xiii, lvi-lvii.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Commissioner's Report 1889–1891, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Commissioner's Report 1889–1891, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Commissioner's Report 1889–1891, p. 22.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1889–1891, p. 23.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1889–1891, p. 129.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Commissioner's Report 1892, p. cvii.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1893, p. 33.

- ↑ Fisheries Historical Timeline: Historical Highlights 1890's

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1893, p. 48.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Commissioner's Report 1893, pp. 32–35.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1893, pp. 86, 88.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1893, p. 46.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 63.4 Commissioner's Report 1893, p. 47.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1894, p. 95.

- ↑ Anonymous, "Anxiety Felt For the Grampus," The New York Times, April 13, 1894.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1894, p. 47.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 Commissioner's Report 1894, p. 93.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Commissioner's Report 1896, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1896, pp. 30, 105.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1896, pp. 11, 35.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1897, p. vi.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1896, p. 37.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1897, p. xxxv.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1897, pp. xviii, xxxiii.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1898, pp. x, l, lii, liii.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1899, p. lv.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1899, pp. xxiii, cxxx.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1899, pp. xii, xxxvi.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1900, pp. 18, 122.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1900, p. 44.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1900, pp. 28, 32, 46.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1901, p. 128.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1901, pp. 2, 23, 199.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1900, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1901, p. 297.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 Commissioner's Report 1902, p. 124.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1902, p. 38.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1902, p. 36.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 Commissioner's Report 1903, p. 22.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1903, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Commissioner's Report 1903, p. 85.

- ↑ "Fisheries Historical Timeline: Historical Highlights 1900's". NOAA Fisheries Service: Northeast Fisheries Science Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). June 16, 2011. http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/history/timeline/1900.html.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Commissioner's Report 1905, p. 37.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1906, pp. 20–24.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Commissioner's Report 1906, p. 24.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1906, p. 20.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Commissioner's Report 1907, p. 18.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1907, p. 20.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1909, p. 16.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 100.2 Commissioner's Report 1909, p. 24.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1910, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 102.2 102.3 102.4 Commissioner's Report 1910, p. 29.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Commissioner's Report 1910, p. 34.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1910, p. 30.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1911, p. 63.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1912, p. 66.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1913, p. 30.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1914, p. 61.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1914, p. 55.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 Commissioner's Report 1915, p. 76.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 Commissioner's Report 1916, p. 112.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 112.2 112.3 112.4 Commissioner's Report 1917, p. 102.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 Commissioner's Report 1917, p. 80.

- ↑ Commissioner's Report 1918, p. 93.

Bibliography

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for 1886. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1889.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for 1887. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1891.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for 1888. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1892.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for 1889 to 1891. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1893.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1892. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1894.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1893. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1895.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1894. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1896.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1895. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1896.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1896. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1898.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1897. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1898.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1898. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1899.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1899. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1900.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1900. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1901.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1901. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1902.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1902. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1904.

- United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1903. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1905.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1905 and Special Papers. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1906 and Special Papers. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1907 and Special Papers. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1909.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1909 and Special Papers. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1911.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1910 and Special Papers. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1911.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1911 and Special Papers. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1913.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1912 and Special Papers. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1914.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1913 and Special Papers. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1914.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1914 and Special Papers. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1915.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1915 and Special Papers. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1917.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1916 with Appendixes. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1917.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1917 with Appendixes. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1919.

- Bureau of Fisheries. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1918 with Appendixes. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1920.